Jun 21, 2025·8 min

How Dependency Injection Boosts Testability and Modularity

Learn how dependency injection makes code easier to test, refactor, and extend. Explore practical patterns, examples, and common pitfalls to avoid.

Learn how dependency injection makes code easier to test, refactor, and extend. Explore practical patterns, examples, and common pitfalls to avoid.

Dependency Injection (DI) is a simple idea: instead of a piece of code creating the things it needs, you give it those things from the outside.

Those “things it needs” are its dependencies—for example, a database connection, a payment service, a clock, a logger, or an email sender. If your code reaches out and builds these dependencies itself, it quietly locks in how those dependencies work.

Think of a coffee machine at an office. It depends on water, coffee beans, and electricity.

DI is that second approach: the “coffee machine” (your class/function) focuses on making coffee (its job), while the “supplies” (dependencies) are provided by whoever sets it up.

DI is not a requirement to use a specific framework, and it’s not the same as a DI container. You can do DI manually by passing dependencies as parameters (or via constructors) and be done.

DI also isn’t “mocking.” Mocking is one possible way to use DI in tests, but DI itself is just a design choice about where dependencies are created.

When dependencies are provided from the outside, your code becomes easier to run in different contexts: production, unit tests, demos, and future features.

That same flexibility makes modules cleaner: pieces can be replaced without rewiring the whole system. As a result, tests get faster and clearer (because you can swap in simple stand-ins), and the codebase becomes easier to change (because parts are less entangled).

Tight coupling happens when one part of your code directly decides what other parts it must use. The most common form is simple: calling new inside your business logic.

Imagine a checkout function that does new StripeClient() and new SmtpEmailSender() internally. At first it feels convenient—everything you need is right there. But it also locks the checkout flow to those exact implementations, configuration details, and even their creation rules (API keys, timeouts, network behavior).

That coupling is “hidden” because it’s not obvious from the method signature. The function looks like it just processes an order, but it secretly depends on payment gateways, email providers, and maybe a database connection too.

When dependencies are hard-coded, even small changes ripple:

Hard-coded dependencies make unit tests run real work: network calls, file I/O, clocks, random IDs, or shared resources. Tests become slow because they’re not isolated, and flaky because results depend on timing, external services, or execution order.

If you see these patterns, tight coupling is likely already costing you time:

new sprinkled “everywhere” in core logicDependency Injection addresses this by making dependencies explicit and swappable—without rewriting the business rules each time the world changes.

Inversion of Control (IoC) is a simple shift in responsibility: a class should focus on what it needs to do, not how to obtain the things it needs.

When a class creates its own dependencies (for example, new EmailService() or opening a database connection directly), it quietly takes on two jobs: business logic and setup. That makes the class harder to change, harder to reuse, and harder to test.

With IoC, your code depends on abstractions—like interfaces or small “contract” types—instead of specific implementations.

For example, a CheckoutService doesn’t need to know whether payments are processed via Stripe, PayPal, or a fake test processor. It just needs “something that can charge a card.” If CheckoutService accepts an IPaymentProcessor, it can work with any implementation that follows that contract.

This keeps your core logic stable even when the underlying tools change.

The practical part of IoC is moving dependency creation out of the class and passing it in (often through the constructor). This is where dependency injection (DI) fits: DI is a common way to achieve IoC.

Instead of:

You get:

The outcome is flexibility: swapping behavior becomes a configuration decision, not a rewrite.

If classes don’t create their dependencies, something else must. That “something else” is the composition root: the place where your application is assembled—typically startup code.

The composition root is where you decide, “In production use RealPaymentProcessor; in tests use FakePaymentProcessor.” Keeping this wiring in one place reduces surprises and keeps the rest of the codebase focused.

IoC makes unit tests simpler because you can provide small, fast test doubles instead of invoking real networks or databases.

It also makes refactors safer: when responsibilities are separated, changing an implementation rarely forces you to change the classes that use it—as long as the abstraction stays the same.

Dependency Injection (DI) isn’t one technique—it’s a small set of ways to “feed” a class the things it depends on (like a logger, database client, or payment gateway). The style you pick affects clarity, testability, and how easy it is to misuse.

With constructor injection, dependencies are required to build the object. That’s the big win: you can’t accidentally forget them.

It’s the best fit when a dependency is:

Constructor injection tends to produce the clearest code and the most straightforward unit tests, because your test can pass a fake or mock right at creation time.

Sometimes a dependency is only needed for a single operation—say, a temporary formatter, a special strategy, or a request-scoped value.

In those cases, pass it as a method parameter. This keeps the object smaller and avoids “promoting” a one-time need into a permanent field.

Setter injection can be convenient when you truly can’t provide a dependency at construction time (some frameworks or legacy code paths). The trade-off is that it can hide requirements: the class looks usable even when it isn’t fully configured.

That often leads to runtime surprises (“why is this undefined?”) and makes tests more fragile because setup becomes easy to miss.

Unit tests are most useful when they’re fast, repeatable, and focused on one behavior. The moment a “unit” test relies on a real database, network call, filesystem, or clock, it tends to slow down and become flaky. Worse, failures stop being informative: did the code break, or did the environment hiccup?

Dependency Injection (DI) fixes this by letting your code accept the things it depends on (database access, HTTP clients, time providers) from the outside. In tests, you can swap those dependencies for lightweight substitutes.

A real DB or API call adds setup time and latency. With DI, you can inject an in-memory repository or a fake client that returns prepared responses instantly. That means:

Without DI, code often “new()s up” its own dependencies, forcing tests to exercise the whole stack. With DI, you can inject:

No hacks, no global switches—just pass a different implementation.

DI makes the setup explicit. Instead of digging through configuration, connection strings, or test-only environment variables, you can read a test and immediately see what’s real and what’s substituted.

A typical DI-friendly test reads like:

Arrange: create the service with a fake repository and a stubbed clock

Act: call the method

Assert: check the return value and/or verify the mock interactions

That directness reduces noise and makes failures easier to diagnose—exactly what you want from unit tests.

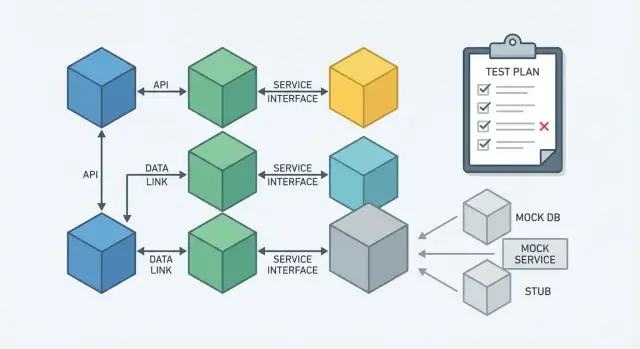

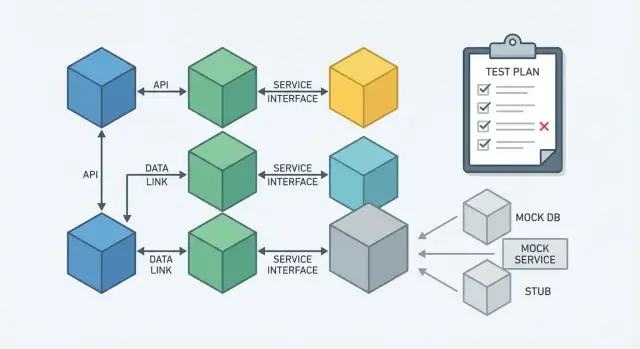

A test seam is a deliberate “opening” in your code where you can swap one behavior for another. In production, you plug in the real thing. In tests, you plug in a safer, faster substitute. Dependency injection is one of the simplest ways to create these seams without hacks.

Seams are most useful around parts of your system that are hard to control in a test:

If your business logic calls these things directly, tests become brittle: they fail for reasons unrelated to your logic (network hiccups, timezone differences, missing files), and they’re harder to run quickly.

A seam often takes the form of an interface—or in dynamic languages, a simple “contract” like “this object must have a now() method.” The key idea is to depend on what you need, not where it comes from.

For example, instead of calling the system clock directly inside an order service, you can depend on a Clock:

SystemClock.now()FakeClock.now() returns a fixed timeThe same pattern works for file reads (FileStore), sending email (Mailer), or charging cards (PaymentGateway). Your core logic stays the same; only the plugged-in implementation changes.

When you can swap behavior on purpose:

Well-placed seams reduce the need for heavy mocking everywhere. Instead, you get a few clean substitution points that keep unit tests fast, focused, and predictable.

Modularity is the idea that your software is built from independent parts (modules) with clear boundaries: each module has a focused responsibility and a well-defined way to interact with the rest of the system.

Dependency injection (DI) supports this by making those boundaries explicit. Instead of a module reaching out to create or find everything it needs, it receives its dependencies from the outside. That small shift reduces how much one module “knows” about another.

When code constructs dependencies internally (for example, new-ing up a database client inside a service), the caller and the dependency become tightly tied together. DI encourages you to depend on an interface (or a simple contract), not a specific implementation.

That means a module typically only needs to know:

PaymentGateway.charge())As a result, modules change less often together, because internal details stop leaking across boundaries.

A modular codebase should let you swap one component without rewriting everyone who uses it. DI makes this practical:

In each case, callers keep using the same contract. The “wiring” changes in one place (composition root), rather than scattered edits across the codebase.

Clear dependency boundaries make it easier for teams to work in parallel. One team can build a new implementation behind an agreed interface while another team continues developing features that depend on that interface.

DI also supports incremental refactoring: you can extract a module, inject it, and replace it gradually—without needing a big-bang rewrite.

Seeing dependency injection (DI) in code makes it click faster than any definition. Here’s a tiny “before and after” using a notification feature.

When a class calls new internally, it decides which implementation to use and how to build it.

class EmailService {

send(to, message) {

// talks to real SMTP provider

}

}

class WelcomeNotifier {

notify(user) {

const email = new EmailService();

email.send(user.email, "Welcome!");

}

}

Testing pain: a unit test risks triggering real email behavior (or requires awkward global stubbing).

test("sends welcome email", () => {

const notifier = new WelcomeNotifier();

notifier.notify({ email: "[email protected]" });

// Hard to assert without patching EmailService globally

});

Now WelcomeNotifier accepts any object that matches the needed behavior.

class WelcomeNotifier {

constructor(emailService) {

this.emailService = emailService;

}

notify(user) {

this.emailService.send(user.email, "Welcome!");

}

}

The test becomes small, fast, and explicit.

test("sends welcome email", () => {

const fakeEmail = { send: vi.fn() };

const notifier = new WelcomeNotifier(fakeEmail);

notifier.notify({ email: "[email protected]" });

expect(fakeEmail.send).toHaveBeenCalledWith("[email protected]", "Welcome!");

});

Want SMS later? You don’t touch WelcomeNotifier. You just pass a different implementation:

const smsService = { send: (to, msg) => {/* SMS provider */} };

const notifier = new WelcomeNotifier(smsService);

That’s the practical payoff: tests stop fighting construction details, and new behavior is added by swapping dependencies instead of rewriting existing code.

Dependency Injection can be as simple as “passing the thing you need into the thing that uses it.” That’s manual DI. A DI container is a tool that automates that wiring. Both can be good choices—the trick is picking the level of automation that matches your app.

With manual DI, you create objects yourself and pass dependencies through constructors (or parameters). It’s straightforward:

Manual wiring also forces good design habits. If an object needs seven dependencies, you feel the pain immediately—which is often a signal to split responsibilities.

As the number of components grows, manual wiring can turn into repetitive “plumbing.” A DI container can help by:

Containers shine in applications with clear boundaries and lifecycles—web apps, long-running services, or systems where many features depend on shared infrastructure.

A container can make a heavily coupled design feel tidy because the wiring disappears. But the underlying issues remain:

If adding a container makes code less readable, or if developers stop knowing what depends on what, you’ve likely gone too far.

Start with manual DI to keep things obvious while you’re shaping your modules. Add a container when the wiring becomes repetitive or lifecycle management gets tricky.

A practical rule: use manual DI inside your core/business code, and (optionally) a container at the app boundary (composition root) to assemble everything. This keeps your design clear while still reducing boilerplate when the project grows.

Dependency injection (DI) can make code easier to test and change—but only if it’s used with discipline. Here are the most common ways DI goes wrong, and habits that keep it helpful.

If a class needs a long list of dependencies, it’s often doing too much. That’s not a DI failure—it’s DI revealing a design smell.

A practical rule of thumb: if you can’t describe the class’s job in one sentence, or the constructor keeps growing, consider splitting the class, extracting a smaller collaborator, or grouping closely related operations behind a single interface (carefully—don’t create “god services”).

The Service Locator pattern typically looks like calling container.get(Foo) from inside your business code. It feels convenient, but it makes dependencies invisible: you can’t tell what a class needs by reading its constructor.

Testing becomes harder because you must set up global state (the locator) instead of supplying a clear, local set of fakes. Prefer passing dependencies explicitly (constructor injection is the most straightforward) so tests can build the object graph with intention.

DI containers can fail at runtime when:

These issues can be frustrating because they show up only when the wiring executes.

Keep constructors small and focused. If a class’s dependency list is growing, treat it as a prompt to refactor.

Add integration tests for wiring. Even a lightweight “composition root” test that builds your application container (or manual wiring) can catch missing registrations and cycles early—before production.

Finally, keep object creation in one place (often your app’s startup/composition root) and keep DI container calls out of business logic. That separation preserves the main benefit of DI: clarity about what depends on what.

Dependency Injection is easiest to adopt when you treat it as a series of small, low-risk refactors. Start where tests are slow or flaky, and where changes regularly ripple through unrelated code.

Look for dependencies that make code hard to test or hard to reason about:

If a function can’t run without reaching outside the process, it’s usually a good candidate.

This approach keeps each change reviewable and lets you stop after any step without breaking the system.

DI can accidentally turn code into “everything depends on everything” if you inject too much.

A good rule: inject capabilities, not details. For example, inject Clock instead of “SystemTime + TimeZoneResolver + NtpClient”. If a class needs five unrelated services, it may be doing too much—consider splitting responsibilities.

Also, avoid passing dependencies through multiple layers “just in case”. Inject only where they’re used; centralize wiring in one place.

If you’re using a code generator or a “vibe-coding” workflow to spin up features quickly, DI becomes even more valuable because it preserves structure as the project grows. For example, when teams use Koder.ai to create React frontends, Go services, and PostgreSQL-backed backends from a chat-driven spec, keeping a clear composition root and DI-friendly interfaces helps ensure the generated code remains easy to test, refactor, and swap integrations (email, payments, storage) without rewriting core business logic.

The rule stays the same: keep object creation and environment-specific wiring at the boundary, and keep business code focused on behavior.

You should be able to point to concrete improvements:

If you want a next step, document your “composition root” and keep it boring: one file that wires dependencies together, while the rest of the code stays focused on behavior.

Dependency Injection (DI) means your code receives the things it needs (database, logger, clock, payment client) from the outside instead of creating them internally.

Practically, that usually looks like passing dependencies into a constructor or function parameter so they’re explicit and swappable.

Inversion of Control (IoC) is the broader idea: a class should focus on what it does, not how it gets its collaborators.

DI is a common technique to achieve IoC by moving dependency creation to the outside and passing dependencies in.

If a dependency is created with new inside business logic, it becomes hard to replace.

That leads to:

DI helps tests stay fast and deterministic because you can inject test doubles instead of using real external systems.

Common swaps:

A DI container is optional. Start with manual DI (pass dependencies explicitly) when:

Consider a container when wiring becomes repetitive or you need lifecycle management (singleton/per-request).

Use constructor injection when the dependency is required for the object to work and used across methods.

Use method/parameter injection when it’s only needed for one call (e.g., request-scoped value, one-off strategy).

Avoid setter/property injection unless you truly need late wiring; add validation to fail fast if it’s missing.

A composition root is the place where you assemble the application: create implementations and pass them into the services that need them.

Keep it near app startup (entry point) so the rest of the codebase stays focused on behavior, not wiring.

A test seam is a deliberate point where behavior can be swapped.

Good places for seams are hard-to-test concerns:

Clock.now())DI creates seams by letting you inject a replacement implementation in tests.

Common pitfalls include:

container.get() inside business code hides real dependencies; prefer explicit parameters.Use a small, repeatable refactor:

Repeat for the next seam; stop anytime without needing a big rewrite.