Jul 08, 2025·8 min

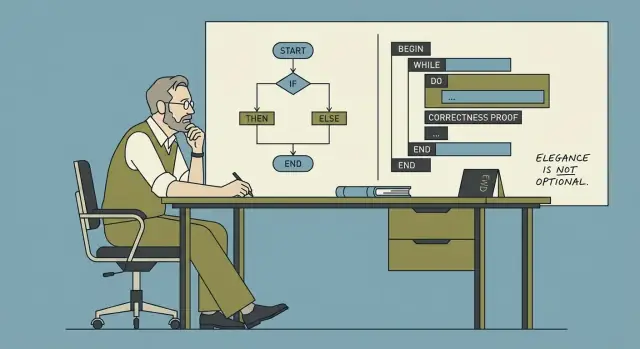

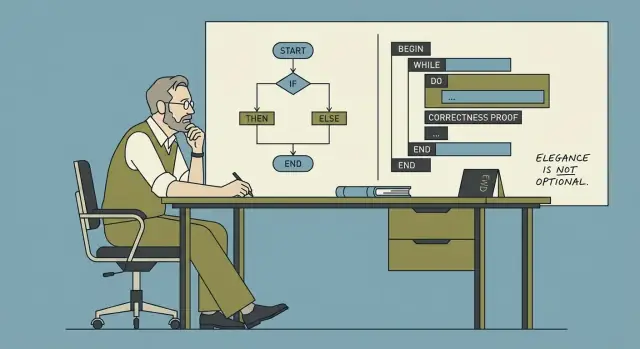

Dijkstra & Structured Programming: Discipline That Scales

Edsger Dijkstra’s structured programming ideas explain why disciplined, simple code stays correct and maintainable as teams, features, and systems grow.

Edsger Dijkstra’s structured programming ideas explain why disciplined, simple code stays correct and maintainable as teams, features, and systems grow.

Software rarely fails because it can’t be written. It fails because, a year later, nobody can change it safely.

As codebases grow, every “small” tweak starts to ripple: a bug fix breaks a distant feature, a new requirement forces rewrites, and a simple refactor turns into a week of careful coordination. The hard part isn’t adding code—it’s keeping behavior predictable while everything around it changes.

Edsger Dijkstra argued that correctness and simplicity should be first-class goals, not nice-to-haves. The payoff isn’t academic. When a system is easier to reason about, teams spend less time firefighting and more time building.

When people say software needs to “scale,” they often mean performance. Dijkstra’s point is different: complexity scales too.

Scale shows up as:

Structured programming is not about being strict for its own sake. It’s about choosing control flow and decomposition that make it easy to answer two questions:

When behavior is predictable, change becomes routine instead of risky. That’s why Dijkstra still matters: his discipline targets the real bottleneck of growing software—understanding it well enough to improve it.

Edsger W. Dijkstra (1930–2002) was a Dutch computer scientist who helped shape how programmers think about building reliable software. He worked on early operating systems, contributed to algorithms (including the shortest-path algorithm that carries his name), and—most importantly for everyday developers—pushed the idea that programming should be something we can reason about, not just something we try until it seems to work.

Dijkstra cared less about whether a program could be made to produce the right output for a few examples, and more about whether we could explain why it is correct for the cases that matter.

If you can state what a piece of code is supposed to do, you should be able to argue (step by step) that it actually does it. That mindset naturally leads to code that’s easier to follow, easier to review, and less dependent on heroic debugging.

Some of Dijkstra’s writing reads uncompromising. He criticized “clever” tricks, sloppy control flow, and coding habits that make reasoning difficult. The strictness isn’t about style policing; it’s about reducing ambiguity. When the code’s meaning is clear, you spend less time debating intentions and more time validating behavior.

Structured programming is the practice of building programs from a small set of clear control structures—sequence, selection (if/else), and iteration (loops)—instead of tangled jumps in flow. The goal is simple: make the path through the program understandable so you can explain, maintain, and change it with confidence.

People often describe software quality as “fast,” “beautiful,” or “feature-rich.” Users experience correctness differently: as the quiet confidence that the app won’t surprise them. When correctness is present, nobody notices. When it’s missing, everything else stops mattering.

“It works now” usually means you tried a few paths and got the expected result. “It keeps working” means it behaves as intended across time, edge cases, and changes—after refactors, new integrations, higher traffic, and new team members touching the code.

A feature can “work now” while still being fragile:

Correctness is about removing these hidden assumptions—or making them explicit.

A minor bug rarely stays minor once software grows. One incorrect state, one off-by-one boundary, or one unclear error-handling rule gets copied into new modules, wrapped by other services, cached, retried, or “worked around.” Over time, teams stop asking “what’s true?” and start asking “what usually happens?” That’s when incident response turns into archaeology.

The multiplier is dependency: a small misbehavior becomes many downstream misbehaviors, each with its own partial fix.

Clear code improves correctness because it improves communication:

Correctness means: for the inputs and situations we claim to support, the system consistently produces the outcomes we promise—while failing in predictable, explainable ways when it can’t.

Simplicity isn’t about making code “cute,” minimal, or clever. It’s about making behavior easy to predict, explain, and modify without fear. Dijkstra valued simplicity because it improves our ability to reason about programs—especially when the codebase and the team grow.

Simple code keeps a small number of ideas in motion at once: clear data flow, clear control flow, and clear responsibilities. It doesn’t force the reader to simulate many alternate paths in their head.

Simplicity is not:

Many systems become hard to change not because the domain is inherently complex, but because we introduce accidental complexity: flags that interact in unexpected ways, special-case patches that never get removed, and layers that exist mostly to work around earlier decisions.

Each extra exception is a tax on understanding. The cost shows up later, when someone tries to fix a bug and discovers that a change in one area subtly breaks several others.

When a design is simple, progress comes from steady work: reviewable changes, smaller diffs, and fewer emergency fixes. Teams don’t need “hero” developers who remember every historical edge case or can debug under pressure at 2 a.m. Instead, the system supports normal human attention spans.

A practical test: if you keep adding exceptions (“unless…”, “except when…”, “only for this customer…”), you’re probably accumulating accidental complexity. Prefer solutions that reduce branching in behavior—one consistent rule beats five special cases, even if the consistent rule is slightly more general than you first imagined.

Structured programming is a simple idea with big consequences: write code so its execution path is easy to follow. In plain terms, most programs can be built from three building blocks—sequence, selection, and repetition—without relying on tangled jumps.

if/else, switch).for, while).When control flow is composed from these structures, you can usually explain what the program does by reading top-to-bottom, without “teleporting” around the file.

Before structured programming became the norm, many codebases leaned heavily on arbitrary jumps (classic goto-style control flow). The problem wasn’t that jumps are always evil; it’s that unrestricted jumping creates execution paths that are hard to predict. You end up asking questions like “How did we get here?” and “What state is this variable in?”—and the code doesn’t answer clearly.

Clear control flow helps humans build a correct mental model. That model is what you rely on when debugging, reviewing a pull request, or changing behavior under time pressure.

When structure is consistent, modification becomes safer: you can change one branch without accidentally affecting another, or refactor a loop without missing a hidden exit path. Readability isn’t just aesthetics—it’s the foundation for changing behavior confidently without breaking what already works.

Dijkstra pushed a simple idea: if you can explain why your code is correct, you can change it with less fear. Three small reasoning tools make that practical—without turning your team into mathematicians.

An invariant is a fact that stays true while a piece of code runs, especially inside a loop.

Example: you’re summing prices in a cart. A useful invariant is: “total equals the sum of all items processed so far.” If that stays true at every step, then when the loop ends, the result is trustworthy.

Invariants are powerful because they focus your attention on what must never break, not just what should happen next.

A precondition is what must be true before a function runs. A postcondition is what the function guarantees after it finishes.

Everyday examples:

In code, a precondition might be “input list is sorted,” and the postcondition might be “output list is sorted and contains the same elements plus the inserted one.”

When you write these down (even informally), design gets sharper: you decide what a function expects and promises, and you naturally make it smaller and more focused.

In reviews, it shifts debate away from style (“I’d write it differently”) toward correctness (“Does this code maintain the invariant?” “Do we enforce the precondition or document it?”).

You don’t need formal proofs to benefit. Pick the buggiest loop or the trickiest state update and add a one-line invariant comment above it. When someone edits the code later, that comment acts like a guardrail: if a change breaks this fact, the code is no longer safe.

Testing and reasoning aim at the same outcome—software that behaves as intended—but they work very differently. Tests discover problems by trying examples. Reasoning prevents whole categories of problems by making the logic explicit and checkable.

Tests are a practical safety net. They catch regressions, verify real-world scenarios, and document expected behavior in a way the whole team can run.

But tests can only show the presence of bugs, not their absence. No test suite covers every input, every timing variation, or every interaction between features. Many “works on my machine” failures come from untested combinations: a rare input, a specific order of operations, or a subtle state that only appears after several steps.

Reasoning is about proving properties of the code: “this loop always terminates,” “this variable is never negative,” “this function never returns an invalid object.” When done well, it rules out entire classes of defects—especially around boundaries and edge cases.

The limitation is effort and scope. Full formal proofs for an entire product are rarely economical. Reasoning works best when applied selectively: core algorithms, security-sensitive flows, money or billing logic, and concurrency.

Use tests broadly, and apply deeper reasoning where failure is expensive.

A practical bridge between the two is to make intent executable:

These techniques don’t replace tests—they tighten the net. They turn vague expectations into checkable rules, making bugs harder to write and easier to diagnose.

“Clever” code often feels like a win in the moment: fewer lines, a neat trick, a one-liner that makes you feel smart. The problem is that cleverness doesn’t scale across time or across people. Six months later, the author forgets the trick. A new teammate reads it literally, misses the hidden assumption, and changes it in a way that breaks behavior. That’s “cleverness debt”: short-term speed bought with long-term confusion.

Dijkstra’s point wasn’t “write boring code” as a style preference—it was that disciplined constraints make programs easier to reason about. On a team, constraints also reduce decision fatigue. If everyone already knows the defaults (how to name things, how to structure functions, what “done” looks like), you stop re-litigating basics in every pull request. That time goes back into product work.

Discipline shows up in routine practices:

A few concrete habits prevent cleverness debt from accumulating:

calculate_total() over do_it()).Discipline isn’t about perfection—it’s about making the next change predictable.

Modularity isn’t just “splitting code into files.” It’s isolating decisions behind clear boundaries, so the rest of the system doesn’t need to know (or care) about internal details. A module hides the messy parts—data structures, edge cases, performance tricks—while exposing a small, stable surface.

When a change request arrives, the ideal outcome is: one module changes, and everything else stays untouched. That’s the practical meaning of “keeping change local.” Boundaries prevent accidental coupling—where updating one feature silently breaks three others because they shared assumptions.

A good boundary also makes reasoning easier. If you can state what a module guarantees, you can reason about the larger program without re-reading its entire implementation every time.

An interface is a promise: “Given these inputs, I will produce these outputs and maintain these rules.” When that promise is clear, teams can work in parallel:

This isn’t about bureaucracy—it’s about creating safe coordination points in a growing codebase.

You don’t need a grand architecture review to improve modularity. Try these lightweight checks:

Well-drawn boundaries turn “change” from a system-wide event into a localized edit.

When software is small, you can “keep it all in your head.” At scale, that stops being true—and the failure modes become familiar.

Common symptoms look like this:

Dijkstra’s core bet was that humans are the bottleneck. Clear control flow, small well-defined units, and code you can reason about aren’t aesthetic choices—they’re capacity multipliers.

In a large codebase, structure acts like compression for understanding. If functions have explicit inputs/outputs, modules have boundaries you can name, and the “happy path” isn’t tangled with every edge case, developers spend less time reconstructing intent and more time making deliberate changes.

As teams grow, communication costs rise faster than line counts. Disciplined, readable code reduces the amount of tribal knowledge required to contribute safely.

That shows up immediately in onboarding: new engineers can follow predictable patterns, learn a small set of conventions, and make changes without needing a long tour of “gotchas.” The code itself teaches the system.

During an incident, time is scarce and confidence is fragile. Code written with explicit assumptions (preconditions), meaningful checks, and straightforward control flow is easier to trace under pressure.

Just as importantly, disciplined changes are easier to roll back. Smaller, localized edits with clear boundaries reduce the chance that a rollback triggers new failures. The result isn’t perfection—it’s fewer surprises, faster recovery, and a system that stays maintainable as years and contributors accumulate.

Dijkstra’s point wasn’t “write code the old way.” It was “write code you can explain.” You can adopt that mindset without turning every feature into a formal proof exercise.

Start with choices that make reasoning cheap:

A good heuristic: if you can’t summarize what a function guarantees in one sentence, it’s probably doing too much.

You don’t need a big refactor sprint. Add structure at the seams:

isEligibleForRefund).These upgrades are incremental: they lower the cognitive load for the next change.

When reviewing (or writing) a change, ask:

If reviewers can’t answer quickly, the code is signaling hidden dependencies.

Comments that restate the code go stale. Instead, write why the code is correct: the key assumptions, edge cases you’re guarding, and what would break if those assumptions change. A short note like “Invariant: total is always the sum of processed items” can be more valuable than a paragraph of narration.

If you want a lightweight place to capture these habits, collect them into a shared checklist (see /blog/practical-checklist-for-disciplined-code).

Modern teams increasingly use AI to accelerate delivery. The risk is familiar: speed today can turn into confusion tomorrow if the generated code is hard to explain.

A Dijkstra-friendly way to use AI is to treat it as an accelerator for structured thinking, not a replacement for it. For example, when building in Koder.ai—a vibe-coding platform where you create web, backend, and mobile apps through chat—you can keep the “reasoning first” habits by making your prompts and review steps explicit:

Even if you eventually export the source code and run it elsewhere, the same principle applies: generated code should be code you can explain.

This is a lightweight “Dijkstra-friendly” checklist you can use during reviews, refactors, or before merging. It’s not about writing proofs all day—it’s about making correctness and clarity the default.

total always equals sum of processed items” prevents subtle bugs.Pick one messy module and restructure control flow first:

Then add a few focused tests around the new boundaries. If you want more patterns like this, browse related posts at /blog.

Because as codebases grow, the main bottleneck becomes understanding—not typing. Dijkstra’s emphasis on predictable control flow, clear contracts, and correctness reduces the risk that a “small change” causes surprising behavior elsewhere, which is exactly what slows teams down over time.

In this context, “scale” is less about performance and more about complexity multiplying:

These forces make reasoning and predictability more valuable than cleverness.

Structured programming favors a small set of clear control structures:

if/else, switch)for, while)The goal isn’t rigidity—it’s making execution paths easy to follow so you can explain behavior, review changes, and debug without “teleporting” through the code.

The problem is unrestricted jumping that creates hard-to-predict paths and unclear state. When control flow becomes tangled, developers waste time answering basic questions like “How did we get here?” and “What state is valid right now?”

Modern equivalents include deeply nested branching, scattered early exits, and implicit state changes that make behavior hard to trace.

Correctness is the “quiet feature” users rely on: the system consistently does what it promises and fails in predictable, explainable ways when it can’t. It’s the difference between “it works in a few examples” and “it keeps working after refactors, integrations, and edge cases show up.”

Because dependencies amplify errors. A small incorrect state or boundary bug gets copied, cached, retried, wrapped, and “worked around” across modules and services. Over time, teams stop asking “what’s true?” and start relying on “what usually happens,” which makes incidents harder and changes riskier.

Simplicity is about few ideas in motion at once: clear responsibilities, clear data flow, and minimal special cases. It’s not about fewer lines or clever one-liners.

A good test is whether behavior remains easy to predict when requirements change. If every new case adds “unless…” rules, you’re accumulating accidental complexity.

An invariant is a fact that should remain true throughout a loop or state transition. A lightweight way to use it:

total equals the sum of processed items”)This makes later edits safer because the next person knows what must not break.

Testing finds bugs by trying examples; reasoning prevents whole categories of bugs by making logic explicit. Tests can’t prove absence of defects because they can’t cover every input or timing. Reasoning is especially valuable for high-cost failure areas (money, security, concurrency).

A practical blend is: broad tests + targeted assertions + clear preconditions/postconditions around critical logic.

Start with small, repeatable moves that reduce cognitive load:

These are incremental “structure upgrades” that make the next change cheaper without requiring a rewrite.