Aug 07, 2025·8 min

Distributed Databases: Trading Consistency for Availability

Learn why distributed databases often relax consistency to stay available during failures, how CAP and quorum work, and when to choose each approach.

Learn why distributed databases often relax consistency to stay available during failures, how CAP and quorum work, and when to choose each approach.

When a database is split across multiple machines (replicas), you get speed and resilience—but you also introduce periods where those machines don’t perfectly agree or can’t reliably talk to each other.

Consistency means: after a successful write, everyone reads the same value. If you update your profile email, the next read—no matter which replica answers—returns the new email.

In practice, systems that prioritize consistency may delay or reject some requests during failures to avoid returning conflicting answers.

Availability means: the system replies to every request, even if some servers are down or disconnected. You might not get the latest data, but you get an answer.

In practice, systems that prioritize availability may accept writes and serve reads even while replicas disagree, then reconcile differences later.

A trade-off means you can’t maximize both goals at the same time in every failure scenario. If replicas can’t coordinate, the database must either:

The right balance depends on what errors you can tolerate: a short outage, or a short period of wrong/old data. Most real systems choose a point in between—and make the trade-off explicit.

A database is “distributed” when it stores and serves data from multiple machines (nodes) that coordinate over a network. To an application, it may still look like one database—but under the hood, requests can be handled by different nodes in different places.

Most distributed databases replicate data: the same record is stored on multiple nodes. Teams do this to:

Replication is powerful, but it immediately raises a question: if two nodes both have a copy of the same data, how do you guarantee they always agree?

On a single server, “down” is usually obvious: the machine is up or it isn’t. In a distributed system, failure is often partial. One node might be alive but slow. A network link might drop packets. A whole rack might lose connectivity while the rest of the cluster keeps running.

This matters because nodes can’t instantly know whether another node is truly down, temporarily unreachable, or just delayed. While they’re waiting to find out, they still have to decide what to do with incoming reads and writes.

With one server, there’s one source of truth: every read sees the latest successful write.

With multiple nodes, “latest” depends on coordination. If a write succeeds on node A but node B can’t be reached, should the database:

That tension—made real by imperfect networks—is why distribution changes the rules.

A network partition is a break in communication between nodes that are supposed to work as one database. The nodes may still be running and healthy, but they can’t reliably exchange messages—because of a failed switch, an overloaded link, a bad routing change, a misconfigured firewall rule, or even a noisy neighbor in a cloud network.

Once a system is spread across multiple machines (often across racks, zones, or regions), you no longer control every hop between them. Networks drop packets, introduce delays, and sometimes split into “islands.” At small scale these events are rare; at large scale they’re routine. Even a short disruption is enough to matter, because databases need constant coordination to agree on what happened.

During a partition, both sides keep receiving requests. If users can write on both sides, each side may accept updates that the other side doesn’t see.

Example: Node A updates a user’s address to “New Street.” At the same time, Node B updates it to “Old Street Apt 2.” Each side believes its write is the most recent—because it has no way to compare notes in real time.

Partitions don’t show up as neat error messages; they show up as confusing behavior:

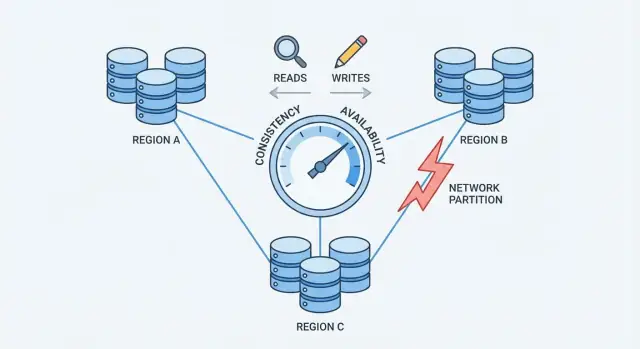

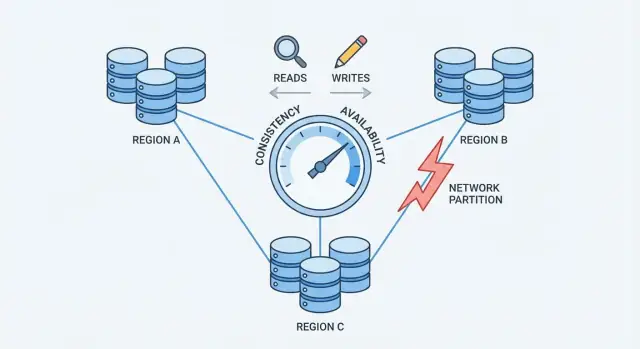

This is the pressure point that forces a choice: when the network can’t guarantee communication, a distributed database must decide whether to prioritize being consistent or being available.

CAP is a compact way to describe what happens when a database is spread across multiple machines.

When there’s no partition, many systems can look both consistent and available.

When there is a partition, you must choose what to prioritize:

balance = 100 to Server A.balance = 80.CAP doesn’t mean “pick only two” as a permanent rule. It means during a partition, you can’t guarantee both Consistency and Availability at the same time. Outside partitions, you can often get very close to both—until the network misbehaves.

Choosing consistency means the database prioritizes “everyone sees the same truth” over “always respond.” In practice, this usually points to strong consistency, often described as linearizable behavior: once a write is acknowledged, any later read (from anywhere) returns that value, as if there were a single up-to-date copy.

When the network splits and replicas can’t reliably talk to each other, a strongly consistent system can’t safely accept independent updates on both sides. To protect correctness, it typically:

From the user’s perspective, this can look like an outage even though some machines are still running.

The main benefit is simpler reasoning. Application code can behave like it’s talking to one database, not several replicas that might disagree. This reduces “weird moments” such as:

You also get cleaner mental models for auditing, billing, and anything that must be correct the first time.

Consistency has real costs:

If your product can’t tolerate failed requests during partial outages, strong consistency may feel expensive—even when it’s the right choice for correctness.

Choosing availability means you optimize for a simple promise: the system responds, even when parts of the infrastructure are unhealthy. In practice, “high availability” isn’t “no errors ever”—it’s that most requests still get an answer during node failures, overloaded replicas, or broken network links.

When the network splits, replicas can’t reliably talk to each other. An availability-first database typically keeps serving traffic from the reachable side:

This keeps applications moving, but it also means different replicas may temporarily accept different truths.

You get better uptime: users can still browse, place items in a cart, post comments, or record events even if a region is isolated.

You also get a smoother user experience under stress. Instead of timeouts, your app can continue with reasonable behavior (“your update is saved”) and sync later. For many consumer and analytics workloads, that trade is worth it.

The price is that the database may return stale reads. A user might update a profile on one replica, then immediately read from another replica and see the old value.

You also risk write conflicts. Two users (or the same user in two locations) can update the same record on different sides of a partition. When the partition heals, the system must reconcile divergent histories. Depending on the rules, one write may “win,” fields may merge, or the conflict may require application logic.

Availability-first design is about accepting temporary disagreement so the product keeps responding—then investing in how you detect and repair the disagreement later.

Quorums are a practical “voting” technique many replicated databases use to balance consistency and availability. Instead of trusting a single replica, the system asks enough replicas to agree.

You’ll often see quorums described with three numbers:

A common rule of thumb is: if R + W > N, then every read overlaps with the latest successful write on at least one replica, which reduces the chance of reading stale data.

If you have N=3 replicas:

Some systems go further with W=3 (all replicas) for stronger consistency, but that can cause more write failures when any replica is slow or down.

Quorums don’t eliminate partition problems—they define who is allowed to make progress. If the network splits 2–1, the side with 2 replicas can still satisfy R=2 and W=2, while the isolated single replica can’t. That reduces conflicting updates, but it means some clients will see errors or timeouts.

Quorums usually mean higher latency (more nodes to contact), higher cost (more cross-node traffic), and more nuanced failure behavior (timeouts can look like unavailability). The benefit is a tunable middle ground: you can dial R and W toward fresher reads or higher write success depending on what matters most.

Eventual consistency means replicas are allowed to be temporarily out of sync, as long as they converge to the same value later.

Think of a chain of coffee shops updating a shared “sold out” sign for a pastry. One store marks it sold out, but the update reaches other stores a few minutes later. During that window, another store might still show “available” and sell the last one. Nobody’s system is “broken”—the updates are just catching up.

When data is still propagating, clients can observe behaviors that feel surprising:

Eventual consistency systems typically add background mechanisms to reduce inconsistency windows:

It’s a good fit when being available matters more than being perfectly current: activity feeds, view counters, recommendations, cached profiles, logs/telemetry, and other non-critical data where “correct in a moment” is acceptable.

When a database accepts writes on multiple replicas, it can end up with conflicts: two (or more) updates to the same item that happened independently on different replicas before those replicas could sync.

A classic example is a user updating their shipping address on one device while also changing their phone number on another. If each update lands on a different replica during a temporary disconnect, the system must decide what the “true” record is once replicas exchange data again.

Many systems start with last-write-wins: whichever update has the newest timestamp overwrites the others.

It’s attractive because it’s easy to implement and fast to compute. The downside is that it can silently lose data. If “newest” wins, then an older-but-important change is discarded—even if the two updates touched different fields.

It also assumes timestamps are trustworthy. Clock skew between machines (or clients) can cause the “wrong” update to win.

Safer conflict handling usually requires tracking causal history.

At a conceptual level, version vectors (and simpler variants) attach a small piece of metadata to each record that summarizes “which replica has seen which updates.” When replicas exchange versions, the database can detect whether one version includes another (no conflict) or whether they diverged (conflict that needs resolution).

Some systems use logical timestamps (e.g., Lamport clocks) or hybrid logical clocks to reduce reliance on wall-clock time while still providing an ordering hint.

Once a conflict is detected, you have choices:

The best approach depends on what “correct” means for your data—sometimes losing a write is acceptable, and sometimes it’s a business-critical bug.

Picking a consistency/availability posture isn’t a philosophical debate—it’s a product decision. Start by asking: what’s the cost of being wrong for a moment, and what’s the cost of saying “try again later”?

Some domains need a single, authoritative answer at write time because “almost correct” is still wrong:

If the impact of a temporary mismatch is low or reversible, you can usually lean more available.

Many user experiences work fine with slightly old reads:

Be explicit about how stale is okay: seconds, minutes, or hours. That time budget drives your replication and quorum choices.

When replicas can’t agree, you typically end up with one of three UX outcomes:

Pick the least damaging option per feature, not globally.

Lean C (consistency) if: wrong results create financial/legal risk, security issues, or irreversible actions.

Lean A (availability) if: users value responsiveness, stale data is tolerable, and conflicts can be resolved safely later.

When in doubt, split the system: keep critical records strongly consistent, and let derived views (feeds, caches, analytics) optimize for availability.

You rarely have to pick a single “consistency setting” for an entire system. Many modern distributed databases let you choose consistency per operation—and smart applications take advantage of that to keep user experience smooth without pretending the trade-off doesn’t exist.

Treat consistency like a dial you turn based on what the user is doing:

This avoids paying the strongest consistency cost for everything, while still protecting the operations that truly need it.

A common pattern is strong for writes, weaker for reads:

In some cases, the reverse works: fast writes (queued/eventual) plus strong reads when confirming a result (“Did my order place?”).

When networks wobble, clients retry. Make retries safe with idempotency keys so “submit order” executed twice doesn’t create two orders. Store and reuse the first result when the same key is seen again.

For multi-step actions across services, use a saga: each step has a corresponding compensating action (refund, release reservation, cancel shipment). This keeps the system recoverable even when parts temporarily disagree or fail.

You can’t manage the consistency/availability trade-off if you can’t see it. Production issues often look like “random failures” until you add the right measurements and tests.

Start with a small set of metrics that map directly to user impact:

If you can, tag metrics by consistency mode (quorum vs. local) and region/zone to spot where behavior diverges.

Don’t wait for the real outage. In staging, run chaos experiments that simulate:

Verify not just “the system stays up,” but what guarantees hold: do reads stay fresh, do writes block, do clients get clear errors?

Add alerts for:

Finally, make the guarantees explicit: document what your system promises during normal operation and during partitions, and educate product and support teams on what users might see and how to respond.

If you’re exploring these trade-offs in a new product, it helps to validate assumptions early—especially around failure modes, retry behavior, and what “stale” looks like in the UI.

One practical approach is to prototype a small version of the workflow (write path, read path, retry/idempotency, and a reconciliation job) before committing to a full architecture. With Koder.ai, teams can spin up web apps and backends via a chat-driven workflow, iterate quickly on data models and APIs, and test different consistency patterns (for example, strict writes + relaxed reads) without the overhead of a traditional build pipeline. When the prototype matches the desired behavior, you can export the source code and evolve it into production.

In a replicated database, the “same” data lives on multiple machines. That boosts resilience and can lower latency, but it introduces coordination problems: nodes can be slow, unreachable, or split by the network, so they can’t always agree instantly on the latest write.

Consistency means: after a successful write, any later read returns that same value—no matter which replica serves it. In practice, systems often enforce this by delaying or rejecting reads/writes until enough replicas (or a leader) confirm the update.

Availability means the system returns a non-error response to every request, even when some nodes are down or can’t communicate. The response might be stale, partial, or based on local knowledge, but the system avoids blocking users during failures.

A network partition is a break in communication between nodes that should act like one system. Nodes may still be healthy, but messages can’t reliably cross the split, which forces the database to choose between:

During a partition, both sides can accept updates they can’t immediately share. That can lead to:

These are user-visible outcomes of replicas being temporarily unable to coordinate.

It doesn’t mean “pick two forever.” It means when a partition happens, you can’t guarantee both:

Outside partitions, many systems can appear to offer both most of the time—until the network misbehaves.

Quorums use voting across replicas:

A common guideline is R + W > N to reduce stale reads. Quorums don’t remove partitions; they define which side can make progress (e.g., the side that still has a majority).

Eventual consistency allows replicas to be temporarily out of sync as long as they converge later. Common anomalies include:

Systems often mitigate this with , , and periodic reconciliation.

Conflicts happen when different replicas accept different writes to the same item during a disconnect. Resolution strategies include:

Pick a strategy based on what “correct” means for your data.

Decide based on business risk and the failure mode your users can tolerate:

Practical patterns include per-operation consistency levels, safe retries with idempotency keys, and with compensation for multi-step workflows.