Aug 13, 2025·6 min

Distributed systems concepts: Kleppmann ideas for SaaS scaling

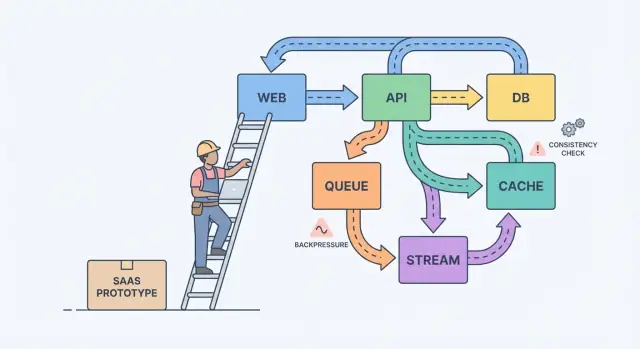

Distributed systems concepts explained through the real choices teams face when turning a prototype into a reliable SaaS: data flow, consistency, and load control.

From prototype to SaaS: where the confusion starts

A prototype proves an idea. A SaaS has to survive real usage: peak traffic, messy data, retries, and customers who notice every hiccup. That’s where things get confusing, because the question shifts from “does it work?” to “does it keep working?”

With real users, “it worked yesterday” fails for boring reasons. A background job runs later than usual. One customer uploads a file that’s 10x bigger than your test data. A payment provider stalls for 30 seconds. None of this is exotic, but the ripple effects get loud once parts of your system depend on each other.

Most of the complexity shows up in four places: data (the same fact exists in multiple places and drifts), latency (50 ms calls sometimes take 5 seconds), failures (timeouts, partial updates, retries), and teams (different people shipping different services on different schedules).

A simple mental model helps: components, messages, and state.

Components do work (web app, API, worker, database). Messages move work between components (requests, events, jobs). State is what you remember (orders, user settings, billing status). Scaling pain is usually a mismatch: you send messages faster than a component can handle, or you update state in two places without a clear source of truth.

A classic example is billing. A prototype might create an invoice, send an email, and update a user’s plan in one request. Under load, email slows down, the request times out, the client retries, and now you have two invoices and one plan change. Reliability work is mostly about preventing those everyday failures from becoming customer-facing bugs.

Turn concepts into written decisions

Most systems get harder because they grow without agreement on what must be correct, what just needs to be fast, and what should happen when something fails.

Start by drawing a boundary around what you’re promising users. Inside that boundary, name the actions that must be correct every time (money movement, access control, account ownership). Then name the areas where “eventually correct” is fine (analytics counts, search indexes, recommendations). This one split turns fuzzy theory into priorities.

Next, write down your source of truth. It’s where facts are recorded once, durably, with clear rules. Everything else is derived data built for speed or convenience. If a derived view is corrupted, you should be able to rebuild it from the source of truth.

When teams get stuck, these questions usually surface what matters:

- What data must never be lost, even if it slows things down?

- What can be recreated from other data, even if it takes hours?

- What’s allowed to be stale, and for how long, from a user’s point of view?

- Which failure is worse for you: duplicates, missing events, or delays?

If a user updates their billing plan, a dashboard can lag. But you can’t tolerate a mismatch between payment status and actual access.

Streams, queues, and logs: choosing the right shape of work

If a user clicks a button and must see the result right away (save profile, load dashboard, check permissions), a normal request-response API is usually enough. Keep it direct.

As soon as work can happen later, move it to async. Think sending emails, charging cards, generating reports, resizing uploads, or syncing data to search. The user shouldn’t wait for these, and your API shouldn’t be tied up while they run.

A queue is a to-do list: each task should be handled once by one worker. A stream (or log) is a record: events are kept in order so multiple readers can replay them, catch up, or build new features later without changing the producer.

A practical way to choose:

- Use request-response when the user needs an immediate answer and the work is small.

- Use a queue for background work with retries where only one worker should perform each job.

- Use a stream/log when you need replay, an audit trail, or multiple consumers that shouldn’t be coupled to one service.

Example: your SaaS has a “Create invoice” button. The API validates input and stores the invoice in Postgres. Then a queue handles “send invoice email” and “charge card.” If you later add analytics, notifications, and fraud checks, a stream of InvoiceCreated events lets each feature subscribe without turning your core service into a maze.

Event design: what you publish and what you keep

As a product grows, events stop being “nice to have” and become a safety net. Good event design comes down to two questions: what facts do you record, and how can other parts of the product react without guessing?

Start with a small set of business events. Pick moments that matter to users and money: UserSignedUp, EmailVerified, SubscriptionStarted, PaymentSucceeded, PasswordResetRequested.

Names outlive code. Use past tense for completed facts, keep them specific, and avoid UI wording. PaymentSucceeded stays meaningful even if you later add coupons, retries, or multiple payment providers.

Treat events as contracts. Avoid a catch-all like “UserUpdated” with a grab bag of fields that change every sprint. Prefer the smallest fact you can stand behind for years.

To evolve safely, favor additive changes (new optional fields). If you need a breaking change, publish a new event name (or explicit version) and run both until old consumers are gone.

What should you store? If you only keep the latest rows in a database, you lose the story of how you got there.

Raw events are great for audit, replay, and debugging. Snapshots are great for fast reads and quick recovery. Many SaaS products use both: store raw events for key workflows (billing, permissions) and maintain snapshots for user-facing screens.

Consistency tradeoffs users actually feel

Build and earn credits

Share what you build or refer others and earn credits to keep iterating.

Consistency shows up as moments like: “I changed my plan, why does it still say Free?” or “I sent an invite, why can’t my teammate log in yet?”

Strong consistency means once you get a success message, every screen should reflect the new state right away. Eventual consistency means the change spreads over time, and for a short window different parts of the app may disagree. Neither is “better.” You choose based on the damage a mismatch can cause.

Strong consistency usually fits money, access, and safety: charging a card, changing a password, revoking API keys, enforcing seat limits. Eventual consistency often fits activity feeds, search, analytics dashboards, “last seen,” and notifications.

If you accept staleness, design for it instead of hiding it. Keep the UI honest: show an “Updating…” state after a write until confirmation arrives, offer a manual refresh for lists, and use optimistic UI only when you can roll back cleanly.

Retries are where consistency gets sneaky. Networks drop, clients double-click, and workers restart. For important operations, make requests idempotent so repeating the same action doesn’t create two invoices, two invites, or two refunds. A common approach is an idempotency key per action plus a server-side rule to return the original result for repeats.

Backpressure: keeping the system from melting down

Backpressure is what you need when requests or events arrive faster than your system can handle. Without it, work piles up in memory, queues grow, and the slowest dependency (often the database) decides when everything fails.

In plain terms: your producer keeps talking while your consumer is drowning. If you keep accepting more work, you don’t just get slower. You trigger a chain reaction of timeouts and retries that multiplies load.

The warning signs are usually visible before an outage: backlog only grows, latency jumps after spikes or deploys, retries rise with timeouts, unrelated endpoints fail when one dependency slows, and database connections sit at the limit.

When you hit that point, pick a clear rule for what happens when you’re full. The goal isn’t to process everything at any cost. It’s to stay alive and recover quickly. Teams typically start with one or two controls: rate limits (per user or API key), bounded queues with a defined drop/delay policy, circuit breakers for failing dependencies, and priorities so interactive requests win over background jobs.

Protect the database first. Keep connection pools small and predictable, set query timeouts, and put hard limits on expensive endpoints like ad-hoc reports.

A step-by-step path to reliability (without rewriting everything)

Reliability rarely requires a big rewrite. It usually comes from a few decisions that make failures visible, contained, and recoverable.

Start with the flows that earn or lose trust, then add safety rails before adding features:

-

Map critical paths. Write down the exact steps for signup, login, password reset, and any payment flow. For each step, list its dependencies (database, email provider, background worker). This forces clarity about what must be immediate versus what can be fixed “eventually.”

-

Add observability basics. Give every request an ID that appears in logs. Track a small set of metrics that match user pain: error rate, latency, queue depth, and slow queries. Add traces only where requests cross services.

-

Isolate slow or flaky work. Anything that talks to an external service or regularly takes more than a second should move to jobs and workers.

-

Design for retries and partial failures. Assume timeouts happen. Make operations idempotent, use backoff, set time limits, and keep user-facing actions short.

-

Practice recovery. Backups matter only if you can restore them. Use small releases and keep a fast rollback path.

If your tooling supports snapshots and rollback (Koder.ai does), build that into normal deployment habits instead of treating it as an emergency trick.

Example: turning a small SaaS into something dependable

From concept to code

Model components, messages, and state, then implement them directly from chat.

Picture a small SaaS that helps teams onboard new clients. The flow is simple: a user signs up, picks a plan, pays, and receives a welcome email plus a few “getting started” steps.

In the prototype, everything happens in one request: create account, charge card, flip “paid” on the user, send email. It works until traffic grows, retries happen, and external services slow down.

To make it dependable, the team turns key actions into events and keeps an append-only history. They introduce a few events: UserSignedUp, PaymentSucceeded, EntitlementGranted, WelcomeEmailRequested. That gives them an audit trail, makes analytics easier, and lets slow work happen in the background without blocking signup.

A few choices do most of the work:

- Treat payments as the source of truth for access, not a single “paid” flag.

- Grant entitlements from

PaymentSucceededwith a clear idempotency key so retries don’t double-grant. - Send emails from a queue/worker, not from the checkout request.

- Record events even if a handler fails, so you can replay and recover.

- Add timeouts and a circuit breaker around external providers.

If payment succeeds but access isn’t granted yet, users feel scammed. The fix isn’t “perfect consistency everywhere.” It’s deciding what must be consistent right now, then reflecting that decision in the UI with a state like “Activating your plan” until EntitlementGranted lands.

On a bad day, backpressure makes the difference. If the email API stalls during a marketing campaign, the old design times out checkouts and users retry, creating duplicate charges and duplicate emails. In the better design, checkout succeeds, email requests queue up, and a replay job drains the backlog once the provider recovers.

Common traps when systems scale

Most outages aren’t caused by one heroic bug. They come from small decisions that made sense in a prototype and then became habits.

One common trap is splitting into microservices too early. You end up with services that mostly call each other, unclear ownership, and changes that require five deploys instead of one.

Another trap is using “eventual consistency” as a free pass. Users don’t care about the term. They care that they clicked Save and later the page shows old data, or an invoice status flips back and forth. If you accept delay, you still need user feedback, timeouts, and a definition of “good enough” on each screen.

Other repeat offenders: publishing events without a reprocessing plan, unbounded retries that multiply load during incidents, and letting every service talk directly to the same database schema so one change breaks many teams.

Quick checks before you call it “production ready”

Release with confidence

Ship small changes with snapshots and rollback ready when real traffic surprises you.

“Production ready” is a set of decisions you can point to at 2 a.m. Clarity beats cleverness.

Start by naming your sources of truth. For each key data type (customers, subscriptions, invoices, permissions), decide where the final record lives. If your app reads “truth” from two places, you’ll eventually show different answers to different users.

Then look at retries. Assume every important action will run twice at some point. If the same request hits your system twice, can you avoid double charging, double sending, or double creating?

A small checklist that catches most painful failures:

- For each data type, you can point to a source of truth and name what’s derived.

- Every important write is safe to retry (idempotency key or a unique constraint).

- Your async work can’t grow without bound (you track lag, oldest message age, and alert before users notice).

- You have a plan for change (reversible migrations, event versioning).

- You can roll back and restore with confidence because you’ve practiced.

Next steps: make one decision at a time

Scaling gets easier when you treat system design as a short list of choices, not a pile of theory.

Write down 3 to 5 decisions you expect to face in the next month, in plain language: “Do we move email sending to a background job?” “Do we accept slightly stale analytics?” “Which actions must be immediately consistent?” Use that list to align product and engineering.

Then pick one workflow that’s currently synchronous and convert only that to async. Receipts, notifications, reports, and file processing are common first moves. Measure two things before and after: user-facing latency (did the page feel faster?) and failure behavior (did retries create duplicates or confusion?).

If you want to prototype these changes quickly, Koder.ai (koder.ai) can be useful for iterating on a React + Go + PostgreSQL SaaS while keeping rollback and snapshots close at hand. The bar stays simple: ship one improvement, learn from real traffic, then decide the next one.

FAQ

What’s the real difference between a prototype and a production SaaS?

A prototype answers “can we build it?” A SaaS must answer “will it keep working when users, data, and failures show up?”

The biggest shift is designing for:

- slow dependencies (email, payments, file processing)

- retries and duplicates

- data that grows and gets messy

- clear rules about what must be correct vs what can be slightly stale

How do I decide what must be strongly consistent vs eventually consistent?

Pick a boundary around what you promise users, then label actions by impact.

Start with must be correct every time:

- charging/refunding money

- access control and entitlements

- account ownership and security actions

Then mark can be eventually correct:

- analytics counters

- search indexes

- notifications and activity feeds

Write it down as a short decision so everyone builds to the same rules.

What does “source of truth” mean in a SaaS, and how do I pick it?

Choose one place where each “fact” is recorded once and treated as final (often Postgres for a small SaaS). That is your source of truth.

Everything else is derived for speed or convenience (caches, read models, search indexes). A good test: if the derived data is wrong, can you rebuild it from the source of truth without guessing?

When should I move work to async instead of keeping it in the API request?

Use request-response when the user needs an immediate result and the work is small.

Move work to async when it can happen later or can be slow:

- sending emails

- charging cards (often after validation)

- report generation

- file processing

Async keeps your API fast and reduces timeouts that trigger client retries.

What’s the difference between a queue and a stream, and which should I use?

A queue is a to-do list: each job should be handled once by one worker (with retries).

A stream/log is a record of events in order: multiple consumers can replay it to build features or recover.

Practical default:

- queue for background tasks (“send welcome email”)

- stream/log for business events you may want to replay or audit (“PaymentSucceeded”)

How do I prevent duplicate charges or duplicate invoices when retries happen?

Make important actions idempotent: repeating the same request should return the same outcome, not create a second invoice or charge.

Common pattern:

- client sends an idempotency key per action

- server stores the result keyed by that value

- repeats return the original result

Also use unique constraints where possible (for example, one invoice per order).

What makes an event “well designed” as my product grows?

Publish a small set of stable business facts, named in past tense, like PaymentSucceeded or SubscriptionStarted.

Keep events:

- specific (avoid “UserUpdated” catch-alls)

- durable (treat as a contract)

- easy to evolve (add optional fields; if breaking, publish a new name/version)

This keeps consumers from guessing what happened.

What are the warning signs I need backpressure, and what should I implement first?

Common signs your system needs backpressure:

- queue backlog only grows

- latency spikes after traffic bursts or deploys

- retries increase because of timeouts

- one slow dependency causes unrelated endpoints to fail

- database connections hit limits

Good first controls:

- rate limits per user/API key

- bounded queues (with a clear drop/delay policy)

- circuit breakers around failing dependencies

- priority so interactive requests win over background jobs

What observability do I need before scaling further?

Start with basics that match user pain:

- a request ID that shows up in logs end-to-end

- metrics for error rate, latency, queue depth, and slow queries

- alerts on “oldest message age” for queues (not just size)

Add tracing only where requests cross services; don’t instrument everything before you know what you’re looking for.

What should be on my “production ready” checklist before real users arrive?

“Production ready” means you can answer hard questions quickly:

- For each data type, where is the source of truth?

- Can every important write be retried safely (idempotency key or unique constraint)?

- Is async work bounded and monitored (lag/oldest message age)?

- Can you roll back releases quickly?

- Can you restore from backups because you’ve practiced?

If your platform supports snapshots and rollback (like Koder.ai), use them as a normal release habit, not only during incidents.