Sep 20, 2025·8 min

Douglas Crockford and JSON: Why Every App Speaks It

How Douglas Crockford popularized JSON and why it became the default language for web apps and APIs—plus practical tips for using JSON well today.

JSON in Plain English: What It Is and Why It Matters

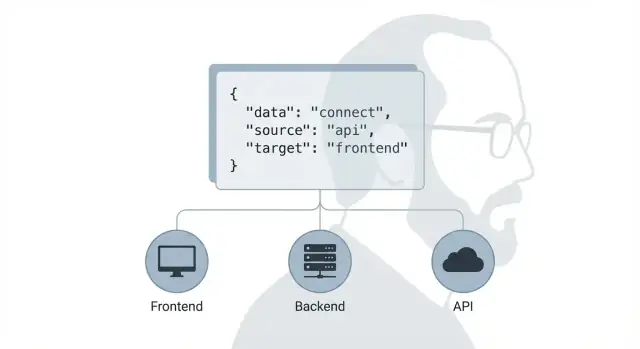

JSON (JavaScript Object Notation) is a lightweight way to represent data as plain text using key–value pairs and lists.

If you build web apps—even if you don’t think about “data formats” much—JSON is probably already the glue holding your product together. It’s how a frontend asks for data, how a backend replies, how mobile apps sync state, and how third-party services send events. When JSON is clear and consistent, teams ship faster; when it’s messy, every feature takes longer because everyone is arguing about what the data “means.”

A tiny example

Here’s a small JSON object you can read at a glance:

{

"userId": 42,

"name": "Sam",

"isPro": true,

"tags": ["beta", "newsletter"]

}

Even without technical context, you can usually infer what’s going on: a user has an ID, a name, a status flag, and a list of tags.

What you’ll get from this article

You’ll learn:

- Where JSON came from and how it became mainstream (including Douglas Crockford’s role)

- Why its “minimal” design is a big part of why it won

- Why JSON fits so naturally with APIs and HTTP

- Practical guidance for using JSON well—so payloads stay understandable as your app grows

The goal is simple: help you understand not just what JSON is, but why nearly every app “speaks” it—and how to avoid the common mistakes teams keep repeating.

Douglas Crockford’s Role in Making JSON Mainstream

Douglas Crockford didn’t “invent” every idea behind JSON, but he did something just as important: he made a simple, workable pattern visible, named it, and pushed it into the mainstream.

The early-web problem: data exchange was messy

In the early days of web applications, teams were juggling awkward options for moving data between browser and server. XML was common but verbose. Custom delimiter-based formats were compact but brittle. JavaScript could technically evaluate data as code, but that blurred the line between “data” and “executable script,” which was a recipe for bugs and security issues.

Crockford saw a cleaner path: use a small subset of JavaScript literal syntax that could represent plain data reliably—objects, arrays, strings, numbers, booleans, and null—without extra features.

Naming, documentation, and the “one page you could point to”

One of Crockford’s biggest contributions was social, not technical: he called it JSON (JavaScript Object Notation) and published clear documentation at json.org. That gave teams a shared vocabulary (“we’ll send JSON”) and a reference that was short enough to read and strict enough to implement.

He also promoted JSON as a data format independent of JavaScript as a programming language: many languages could parse and generate it, and it mapped naturally to common data structures.

Standardization milestones people could trust

Adoption accelerates when teams feel safe betting on a format long-term. JSON gradually gained that “safe bet” status through widely known milestones:

- RFC 4627 (2006): early formal description for interoperable implementations

- ECMA-404: a concise standard defining JSON syntax

- RFC 7159 and later RFC 8259 (2017): clarified interoperability and cemented JSON’s place on the internet

Crockford’s advocacy, combined with these standards and a growing ecosystem of parsers, helped JSON move from a handy convention to the default way apps talk—especially across HTTP APIs (covered later in /blog/json-and-apis).

Before JSON: Data Formats the Web Tried to Live With

Before JSON became the default way to move data around, the web relied on a mix of formats that were either too heavy, too inconsistent, or too custom to scale across teams.

What people used before JSON

XML was the big “standard” choice. It worked across languages, had tooling, and could represent nested structures. It also brought a lot of ceremony along for the ride.

At the same time, many apps passed data as custom query strings (especially in early AJAX-style requests): key/value pairs stuffed into URLs or POST bodies. Others invented ad‑hoc text formats—a comma-separated list here, a pipe-delimited blob there—often with hand-rolled escaping rules that only one developer understood.

The pain points teams kept hitting

The common problems weren’t theoretical:

- Verbosity: XML made small payloads feel big, and large payloads feel enormous.

- Parsing complexity: Real-world XML often required heavier parsers and careful handling of namespaces, attributes vs elements, and whitespace.

- Inconsistent conventions: With ad‑hoc formats, every endpoint became its own mini-protocol. Clients had to guess types, encoding, and edge cases.

Why “good enough and simple” wins

Most apps don’t need a format that can express every possible document structure. They need a predictable way to send objects, arrays, strings, numbers, and booleans—quickly, consistently, and with minimal room for interpretation. Simpler formats reduce the number of decisions (and mistakes) teams make per endpoint.

A quick comparison: XML vs JSON

<user>

<id>42</id>

<name>Ada</name>

<isActive>true</isActive>

</user>

{

"id": 42,

"name": "Ada",

"isActive": true

}

Both express the same idea, but JSON is easier to scan, easier to generate, and closer to how most applications already model data in memory.

Why JSON Is Minimal: The Design Choices That Worked

JSON’s staying power isn’t an accident. It succeeds because it’s deliberately small: just enough structure to represent real application data without inviting endless variation.

The smallest useful set of building blocks

JSON gives you a minimal toolkit that maps cleanly to how most apps think about data:

- Objects: named fields (like a contact with

name,email) - Arrays: ordered lists (like items in a cart)

- Strings: text

- Numbers: numeric values (with a few caveats)

- Booleans:

true/false - null: an explicit “no value”

That’s it. No dates, no comments, no custom numeric types, no references. This simplicity makes JSON easy to implement across languages and platforms.

Human-readable, machine-friendly—by design

JSON is readable enough for people to scan in logs and API responses, while remaining easy for machines to parse quickly. It avoids extra ceremony, but keeps clear delimiters ({}, [], :) so parsers can be fast and reliable.

The tradeoff: because JSON is so minimal, teams must agree on conventions for things like timestamps, money, and identifiers (for example, ISO-8601 strings for dates).

Strictness is a feature, not a limitation

JSON’s strict rules (double-quoted strings, no trailing commas, a small fixed set of types) reduce ambiguity. Less ambiguity means fewer “it works on my machine” failures when different systems exchange data.

A misconception worth clearing up

JSON looks like JavaScript object syntax, but JSON is not JavaScript. It’s a language-agnostic data format with its own rules, usable from Python, Java, Go, Ruby, and anywhere else that needs consistent serialization and interoperability.

How JSON Became the Default Between Frontends and Backends

JSON didn’t win because it was the most feature-rich format. It won because it fit the way web apps were already being built: a JavaScript-heavy browser talking to a server over simple HTTP requests.

JavaScript was already on every page

Once browsers standardized around JavaScript, the client side had a built-in way to represent structured data: objects, arrays, strings, numbers, booleans, and null. JSON mirrored those primitives closely, so moving data between “what the browser understands” and “what the server sends” felt natural.

Early Ajax-style apps accelerated this. Instead of returning full HTML pages, servers could return a small payload for the UI to render. A response like this was immediately useful:

{

"user": {"id": 42, "name": "Sam"},

"unreadCount": 3

}

Easy parsing everywhere, not just in browsers

Even though JSON’s syntax looks like JavaScript, it’s language-neutral. As soon as servers and clients in other languages needed to interoperate with web frontends, JSON libraries appeared—and quickly became “standard equipment.” Parsing a JSON string into native data structures is usually one function call, and generating JSON is just as simple.

Tooling snowballed into a default choice

Once frameworks, API clients, debuggers, proxies, and documentation tools assumed JSON, choosing something else created friction. Developers could inspect payloads in browser devtools, copy/paste examples into tests, and rely on mature libraries for encoding, decoding, and error handling.

One payload, many consumers

A single JSON response can serve a web UI, a mobile app, an internal service, and a third-party integration with minimal changes. That interoperability made JSON a safe bet for teams building “one backend, many frontends”—and helped it become the default contract between client and server.

JSON and APIs: The Practical Fit With HTTP

Launch with hosting

Move from prototype to production with hosting and a custom domain when you are ready.

JSON didn’t win because it was fancy—it fit neatly into how the web already worked. HTTP is built around sending a request and getting a response, and JSON is an easy, predictable way to represent the “body” of that response (or request) as structured data.

HTTP + JSON in one minute

An API request usually includes a method and a URL (for example, GET /users?limit=20). The server replies with a status code (like 200 or 404), headers, and an optional body.

When the body is JSON, a key header is:

Content-Type: application/json

That header tells clients how to interpret the bytes they receive. On the way in (client → server), sending Content-Type: application/json signals “I’m posting JSON,” and servers can parse it consistently.

Common API response patterns

JSON works especially well for repeating patterns that show up across many APIs.

Pagination often wraps a list with metadata:

{

"data": [{"id": 1, "name": "A"}],

"pagination": {"limit": 20, "offset": 0, "total": 153}

}

Filtering and sorting typically happen in the URL query string, while results remain a JSON array (or a data field). For example: GET /orders?status=paid&sort=-created_at.

Error responses benefit from a standard shape so clients can display messages and handle retries:

{

"error": {

"code": "invalid_request",

"message": "limit must be between 1 and 100",

"details": {"field": "limit"}

}

}

The practical match is simple: HTTP provides delivery and meaning (verbs, status codes, caching), while JSON provides a lightweight, human-readable structure for the data itself.

JSON vs XML: Why JSON Usually Wins for App Data

When people compare JSON and XML, they’re often really comparing “data for apps” versus “data for documents.” Both formats can represent structured information, but JSON tends to match what most applications actually move around: simple objects, lists, strings, numbers, booleans, and null.

Readability and size: fewer tags, less noise

XML is verbose by design. Repeating opening and closing tags makes payloads larger and harder to scan in logs or network inspectors. JSON typically conveys the same meaning with fewer characters and less visual clutter, which helps during debugging and can reduce bandwidth costs at scale.

This isn’t just about aesthetics: smaller payloads often mean faster transfers and less work for parsers and proxies.

Data model alignment: maps and lists fit app data

Most app data naturally looks like dictionaries (key/value maps) and arrays (lists): a user with attributes, an order with line items, a page with components. JSON maps directly onto that mental model, and it matches native data structures in JavaScript and most modern languages.

XML can represent the same structures, but it usually requires conventions: attributes vs elements, repeated child elements for lists, and extra rules for “what counts as a number” (since everything is text unless you add typing on top).

Where XML can still shine (without dismissing it)

XML remains strong for document-centric use cases: mixed content (text interleaved with markup), publishing workflows, and ecosystems with mature XML tooling (e.g., certain enterprise integrations). If your payload is closer to a document than an object graph, XML can be a good fit.

Guidance: choose based on needs, not trends

If your primary goal is exchanging application data between frontend, backend, and APIs, JSON is usually the simpler, more direct choice. If you need document markup, mixed content, or you’re integrating into an XML-heavy domain, XML may be the better tool.

JSON Rules That Still Surprise Teams

Build a JSON-ready UI

Create a React frontend that consumes your API responses without wiring everything by hand.

JSON looks like “JavaScript objects,” so teams often assume they can treat it like JavaScript. That’s where bugs sneak in: JSON is stricter, smaller, and less forgiving.

The strict syntax rules

A few “it works on my machine” issues show up again and again:

- Double quotes are required for keys and string values.

{name: "Ada"}is not JSON;{ "name": "Ada" }is. - No trailing commas.

{ "a": 1, }will fail in many parsers. - No comments.

//and/* ... */are invalid. If you need notes, keep them in documentation or use a separate field (carefully) during development.

These constraints are intentional: they keep parsers simple and consistent across languages.

Numbers, dates, and decimals: choose types on purpose

JSON has only one numeric type: number. There’s no built-in integer, decimal, or date.

- Money and high-precision decimals (prices, exchange rates) are often safer as strings (e.g.,

"19.99") to avoid rounding differences across systems. - Dates and times should usually be strings in a standard format, most commonly ISO 8601 (e.g.,

"2025-12-26T10:15:30Z"). Avoid custom date formats that require guesswork. - Be careful with very large integers: some environments can’t represent them precisely. When in doubt, send them as strings.

Unicode and escaping in real systems

JSON is Unicode, but real systems still trip over encoding and escaping:

- Ensure everything is consistently UTF-8 over the wire.

- Remember that certain characters must be escaped inside strings (like quotes

"and backslashes\\). - Watch for invisible characters copied from documents (non-breaking spaces, smart quotes) that can break parsing.

Security: parse JSON safely

Always parse JSON with a real JSON parser (JSON.parse or your language’s equivalent). Avoid any eval-style approach, even if it “seems faster.” And validate inputs at the edges—especially for public APIs—so unexpected fields or types don’t slip into business logic.

Designing JSON Payloads That Age Well

A JSON payload isn’t just “data in transit”—it’s a long-term interface between teams, systems, and future you. The difference between a payload that lasts and one that gets rewritten every quarter is usually boring discipline: consistency, careful change management, and predictable edge cases.

Consistency beats cleverness

Pick naming rules and stick to them everywhere:

- Use one casing style (commonly

camelCaseorsnake_case) and don’t mix. - Keep keys stable. Renaming

userIdtoidis a breaking change even if the meaning feels “obvious.” - Prefer explicit fields over “magic” polymorphism. A key that changes type (

"count": 3vs"count": "3") will cause bugs that are hard to trace.

Versioning without drama

You can avoid most version wars by making changes additive:

- Add new optional fields instead of changing or removing existing ones.

- Treat removals as deprecations: keep the old field, stop documenting it for new clients, and announce a removal date.

- If you truly need a breaking change, version the endpoint (

/v2/...) or include a clear version signal in a header—don’t silently change semantics.

Errors should be boringly predictable

Clients handle failures best when errors share one shape:

{

"error": {

"code": "INVALID_ARGUMENT",

"message": "email must be a valid address",

"details": { "field": "email" }

}

}

Documentation that matches reality

Great JSON docs include real examples—successful and failing responses—with complete fields. Keep examples synchronized with production behavior, and call out which fields are optional, nullable, or deprecated. When examples match real responses, integrations go faster and break less.

Where Koder.ai fits (if you’re building APIs fast)

If you’re using a vibe-coding workflow to spin up new features quickly, JSON contracts become even more important: rapid iteration is great until clients and services drift apart.

On Koder.ai, teams commonly generate a React frontend plus a Go + PostgreSQL backend and then iterate through API shapes in planning mode before locking them in. Features like snapshots and rollback help when a “small” JSON change turns out to be breaking, and source code export makes it easy to keep the contract in your repo and enforce it with tests.

Validation and Contracts: JSON Schema and Beyond

JSON is easy to generate, which is both its strength and its trap. If one service sends "age": "27" (string) and another expects 27 (number), nothing in JSON itself will stop it. The result is usually the worst kind of bug: a client crash in production, or a subtle UI glitch that only happens with certain data.

Why validation matters (even for “simple” JSON)

Validation is about catching bad or unexpected data before it reaches the people who rely on it—your frontend, partner integrations, analytics pipeline, or mobile apps.

Common failure points include missing required fields, renamed keys, wrong types, and “almost right” values (like dates in inconsistent formats). A small validation step at the API boundary can turn these from outages into clear error messages.

JSON Schema: what it is and when to use it

JSON Schema is a standard way to describe what your JSON should look like: required properties, allowed types, enums, patterns, and more. It’s most useful when:

- You have multiple clients (web + mobile + partners) consuming the same API

- You need backward-compatible changes over time

- You want automated checks in CI/CD, not just human review

With a schema, you can validate requests on the server, validate responses in tests, and generate documentation. Many teams pair it with their API docs (often via OpenAPI), so the contract is explicit rather than “tribal knowledge.” If you already publish developer docs, linking schema examples from /docs can keep things consistent.

Lightweight alternatives (and complements)

Not every team needs full schema tooling on day one. Practical options include:

- Shared example payloads kept in the repo (golden files)

- Contract tests that verify real responses match expectations

- Consumer-driven contracts (clients define what they require)

A helpful rule: start with examples and contract tests, then add JSON Schema when changes and integrations start to multiply.

Performance and Reliability With JSON at Scale

Add a mobile client

Generate a Flutter app that stays in sync with your backend JSON.

JSON feels “lightweight” when you’re sending a few fields. At scale—mobile clients on shaky networks, high-traffic APIs, analytics-heavy pages—JSON can become a performance problem or a reliability risk if you don’t shape and ship it carefully.

Keep payloads small: page, filter, and avoid overfetching

The most common scaling issue isn’t JSON parsing—it’s sending too much of it.

Pagination is the simple win: return predictable chunks (for example, limit + cursor) so clients don’t download thousands of records at once. For endpoints that return nested objects, consider partial responses: let the client ask for only what it needs (selected fields or “include” expansions). This prevents “overfetching,” where a screen only needs name and status but receives every historical detail and configuration field.

A practical rule: design responses around user actions (what a screen needs now), not around what your database can join.

Compression and caching: fewer bytes, fewer requests

If your API serves large JSON responses, compression can dramatically cut transfer size. Many servers can gzip or brotli responses automatically, and most clients handle it without extra code.

Caching is the other lever. At a high level, aim for:

- Cacheable responses for data that doesn’t change every second

- Clear cache rules (e.g., using ETag or “last modified” patterns)

This reduces repeat downloads and smooths traffic spikes.

Streaming and incremental parsing (when JSON gets huge)

For very large outputs—exports, event feeds, bulk sync—consider streaming responses or incremental parsing so clients don’t have to load an entire document into memory before doing anything useful. It’s not required for most apps, but it’s a valuable option when “one big JSON blob” starts timing out.

Observability: log safely without leaking data

JSON is easy to log, which is both helpful and dangerous. Treat logs as a product surface:

- Avoid logging whole request/response bodies by default

- Redact sensitive fields (tokens, passwords, personal identifiers)

- Prefer structured logs that capture IDs, timing, and error codes over raw payloads

Done well, you’ll debug faster while reducing the risk of accidental data exposure.

What’s Next for JSON and a Simple Best-Practices Checklist

JSON isn’t “finished”—it’s stable. What changes now is the ecosystem around it: stronger editors, better validation, safer API contracts, and more tooling that helps teams avoid accidental breaking changes.

Where JSON is going

JSON will likely stay the default wire format for most web and mobile apps because it’s widely supported, easy to debug, and maps cleanly to common data structures.

The biggest shift is toward typed APIs: teams still send JSON, but they define it more precisely using tools like JSON Schema, OpenAPI, and code generators. That means fewer “guess the shape” moments, better autocomplete, and earlier error detection—without abandoning JSON itself.

Related formats: JSON Lines / NDJSON

When you need to send or store many records efficiently (logs, analytics events, exports), a single giant JSON array can be awkward. JSON Lines (also called NDJSON) solves this by putting one JSON object per line. It streams well, can be processed line-by-line, and plays nicely with command-line tooling.

A simple best-practices checklist

Use this as a quick pre-flight check for payloads that will live longer than a sprint:

- Keep keys consistent and predictable (pick a naming style and stick to it).

- Prefer stable identifiers (don’t make clients depend on array positions).

- Use ISO 8601 timestamps (e.g.,

2025-12-26T10:15:00Z). - Distinguish “missing” vs “empty” vs

nulland document your choice. - Version carefully (add fields freely; remove/rename only with a plan).

- Validate at the edges (server input validation; client-side sanity checks).

- Return helpful errors (machine-readable codes plus human text).

Keep learning

If you want to go deeper, browse related guides on /blog—especially topics like schema validation, API versioning, and designing payloads for long-term compatibility.