Apr 01, 2025·8 min

Douglas Engelbart’s Augmented Intellect: Mouse, Hypertext, Teams

How Douglas Engelbart’s Augmenting Human Intellect work predicted modern productivity software—mouse, hypertext, shared documents, and real-time collaboration.

How Douglas Engelbart’s Augmenting Human Intellect work predicted modern productivity software—mouse, hypertext, shared documents, and real-time collaboration.

Most of us spend our days moving ideas around: writing, revising, searching, sharing, and trying to keep decisions connected to the right context. It feels normal now—but the pattern of “knowledge work” we take for granted was still being invented in the 1960s.

Douglas Engelbart didn’t set out to build a gadget. He set out to improve how people think and coordinate when problems get complex. His research group treated office work as something you could design deliberately, not just speed up with faster machines.

Engelbart used the phrase augmenting human intellect to mean: helping people do better thinking and better teamwork by giving them tools that make ideas easier to create, connect, and act on. Not replacing humans—amplifying them.

Many features in modern productivity software trace back to three core concepts Engelbart pushed forward:

We’ll walk through what Engelbart actually built (especially the NLS oN-Line System) and what was shown in the famous 1968 demonstration often called the “Mother of All Demos.” Then we’ll connect those ideas to tools you already use—docs, wikis, project trackers, and chat—so you can spot what’s working, what’s missing, and why certain workflows feel smooth while others feel like busywork.

Douglas Engelbart’s core contribution wasn’t a single invention—it was a goal. In his 1962 report, Augmenting Human Intellect: A Conceptual Framework, he argued that computers should help people think, learn, and solve complex problems better than they could alone. He called this “augmentation,” and he treated it as a design north star rather than a vague aspiration.

Automation aims to replace human effort: do the task for you, faster and cheaper. That’s useful, but it can also narrow what you’re able to do—especially when work is ambiguous, creative, or involves tradeoffs.

Augmentation is different. The computer doesn’t take over the thinking; it strengthens it. It helps you externalize ideas, move faster through information, spot connections, and revise your understanding as you go. The goal isn’t to eliminate the human—it’s to amplify human judgment.

Engelbart also believed improvement should compound. If better tools make you more capable, you can use that capability to build even better tools, methods, and habits. This loop—improving how we improve—was central to his thinking.

It implies that small upgrades (a better way to structure notes, navigate documents, or coordinate decisions) can have outsized, long-term effects.

Crucially, Engelbart focused on groups. Complex problems rarely live in one person’s head, so augmentation had to include shared context: common documents, common language, and ways to coordinate work without losing the reasoning behind decisions.

That team-first emphasis is why his ideas still map so cleanly onto modern knowledge work.

Engelbart’s NLS (oN-Line System) wasn’t a “computer program” in the way people used that phrase in the 1960s. It was closer to an interactive knowledge workspace: a place where you could create, navigate, revise, and connect information while staying in the flow of your work.

Instead of treating the computer like a remote calculator you fed with cards and waited on, NLS treated it like a partner for thinking—something you could steer moment to moment.

NLS combined capabilities that modern productivity tools often split across documents, wikis, and collaboration apps:

NLS was designed for research, planning, and collaboration: drafting proposals, organizing projects, maintaining knowledge bases, and coordinating decisions.

The point wasn’t to make computers look impressive; it was to make teams more capable.

At the time, many organizations still relied on batch computing (submit a job, wait for results) and paper-based processes (memos, binders, manual version control). NLS replaced waiting and retyping with interactive editing, navigable structure, and connected information—a blueprint for the productivity platforms we take for granted today.

Before Engelbart, most computing interaction was typed: you wrote commands, hit enter, and waited for the machine to respond. That works for calculators and batch jobs, but it breaks down once information lives on the screen as objects you want to manipulate—words, headings, links, files, and views.

If your goal is to speed up knowledge work, you need a faster way to “touch” what you’re thinking about.

Engelbart’s team was building NLS as an environment where people could navigate and edit complex documents, jump between related ideas, and manage multiple views.

In that kind of interface, “go to line 237” is slower and more error-prone than simply pointing at the thing you mean.

A pointing device turns intention into action with less translation: point, select, act. That reduction in mental overhead is part of what made on-screen work feel more like direct manipulation than remote control.

The first mouse was a small wooden device with wheels that tracked movement across a surface and translated it into cursor motion.

Novelty wasn’t just the hardware—it was the pairing of a stable on-screen pointer with quick selection. It let users choose text blocks, activate commands, and move through a structured document without constantly switching into “command language” mode.

Nearly every familiar pattern follows from that same idea: pointing to targets, clicking to select, dragging to move, resizing windows, and working across multiple panes or windows at once.

Even touchscreens echo the same principle: make digital objects feel manipulable.

Engelbart’s group also explored the chording keyboard—pressing key combinations to issue commands quickly with one hand while the other hand pointed.

It’s a reminder that the mouse wasn’t meant to replace typing, but to complement it: one hand for navigation and selection, the other for rapid input and control.

Hypertext is a simple idea with a big effect: information doesn’t have to be read in one fixed order. Instead, you can connect small pieces—notes, paragraphs, documents, people, terms—and jump between them as needed.

A traditional document is like a road: you start at the top and move forward. Hypertext turns information into a map. You can follow what’s relevant right now, skip what isn’t, and still return to the main thread.

That shift changes how you organize knowledge. Rather than forcing everything into one “perfect” outline, you can keep information where it naturally belongs and add links that explain relationships:

Over time, those connections become a second layer of structure—one that reflects how people actually think and work.

You see hypertext every time you click a hyperlink on the web, but it’s just as important inside modern work tools:

Links aren’t only about convenience; they reduce misunderstandings. When a project brief links to the decision log, customer feedback, and current status, the team shares the same context—and new teammates can catch up without a long verbal history.

In practice, good linking is a form of empathy: it anticipates the next question and provides a clear path to the answer.

Engelbart treated a document less like a “page” and more like a structured system. In NLS, information was organized into outlines—nested headings and subpoints you could expand, collapse, rearrange, and reuse.

The unit of work wasn’t a paragraph floating on a canvas; it was a block with a place in a hierarchy.

Structured writing is writing with deliberate shapes: headings, numbered levels, and reusable blocks (sections, bullets, or snippets) that can move without breaking the whole.

When content is modular, editing gets faster because you can:

Modern document editors and knowledge bases quietly reflect this idea. Outliners, docs with heading navigation, and block-based tools all make it easier to treat writing like building.

Task lists are the same pattern: each task is a “block” you can nest under a project, assign, link, and track.

The practical payoff isn’t just neatness. Structure improves clarity (people can scan), speeds up editing (you adjust parts, not everything), and makes collaboration easier (teammates can comment or own specific sections).

Start a “Project Alpha” doc with a simple outline:

As you learn, you don’t rewrite—you refactor. Move a risk from “Notes” into “Scope,” nest tasks under milestones, and add links from each milestone to a dedicated page (meeting notes, specs, or a checklist).

The result is a living map: one place to navigate context, not a long thread to scroll.

Engelbart didn’t picture “collaboration” as emailing documents back and forth. His goal was shared workspaces where the group could see the same material, at the same time, with enough context to make joint decisions quickly.

The unit of work wasn’t a file sitting on one person’s computer—it was a living, navigable body of knowledge the team could continually improve.

When work is split into private drafts, coordination becomes a separate job: collecting versions, reconciling changes, and guessing which copy is current.

Engelbart’s vision reduced that overhead by keeping knowledge in a shared system where updates were immediately visible and linkable.

That “shared context” matters as much as the shared text. It’s the surrounding structure—what this section is connected to, why a change was made, what decision it supports—that prevents teams from rewriting the same thinking repeatedly.

In the famous 1968 demo, Engelbart showed capabilities that feel normal now but were radical then: remote interaction, shared editing, and ways for people to coordinate while looking at the same information.

The point wasn’t simply that two people could type into the same document; it was that a system could support the workflow of collaboration—reviewing, discussing, updating, and moving forward with less friction.

Today’s collaboration software often maps neatly onto these ideas:

These are not nice-to-haves; they’re mechanisms for maintaining shared context when many hands touch the same work.

Even the best platform can’t force good collaboration. Teams still need norms: when to comment vs. edit directly, how decisions get recorded, what “done” means, and who owns the final call.

Engelbart’s deeper insight was that improving knowledge work requires designing both the tools and the practices around them—so coordination becomes a supported habit rather than an ongoing struggle.

Real-time co-editing means multiple people can work on the same document at the same moment—and everyone sees changes appear almost instantly.

Engelbart’s NLS treated this as a coordination problem, not a novelty: the value isn’t just speed of typing, it’s speed of agreement.

When edits are live, decision-making accelerates because the team shares a single, current “source of truth.” Instead of waiting for attachments, copy-pasting updates into chat, or reconciling separate notes, the group can converge in minutes on what changed, what it implies, and what to do next.

Live collaboration works best when you can see what others are trying to do.

A moving cursor, a highlighted selection, or a small activity feed answers practical questions: Who is editing this section? Are they rewriting, adding a reference, or just scanning?

This visibility reduces duplicated work (“I didn’t realize you were already fixing that paragraph”) and makes handoffs smoother (“I’ll take the next section while you finish this one”).

Coordination gets tricky when two people edit the same part.

Modern tools handle this with a few understandable ideas:

Even when the software “auto-merges,” teams still need clarity about intent—why a change was made, not just that it happened.

Real-time co-editing turns collaboration from a relay into a shared workspace—and coordination becomes the main skill the tool is trying to support.

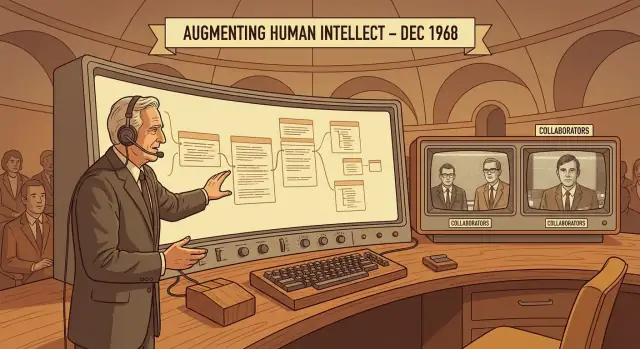

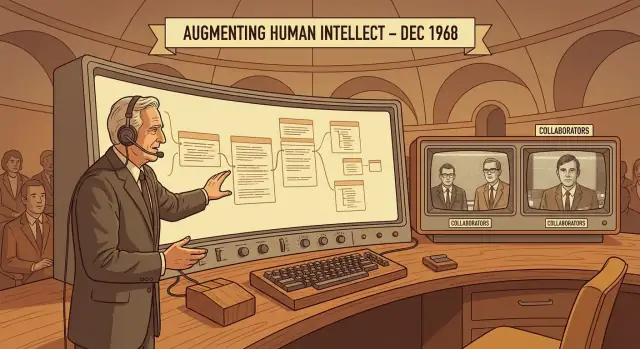

On December 9, 1968, Douglas Engelbart and his team took the stage in San Francisco and ran a live, 90‑minute demonstration of their NLS (oN-Line System).

It later earned the nickname “the Mother of All Demos” because it showed a coherent vision of interactive, connected knowledge work—performed in real time, in front of an audience.

Engelbart didn’t just show a faster way to type. He demonstrated a whole working environment:

The deeper point wasn’t any single gadget. The demo argued that computers could be partners for “knowledge work”: helping people create, organize, and revisit information faster than paper-based workflows allowed.

Just as importantly, it suggested that this work could be networked and collaborative, with shared context instead of isolated files.

It’s tempting to treat 1968 as the moment modern computing suddenly appeared. That’s not what happened.

NLS didn’t immediately become everyone’s office tool, and many parts were expensive, complex, or ahead of available hardware.

What the demo did do was make a persuasive, working case that these ideas were feasible. Later systems—from research labs to commercial software—borrowed and reinterpreted pieces of that vision over time, rather than copying NLS wholesale.

Engelbart didn’t just predict specific features like the mouse or links—he sketched a pattern for how knowledge work should flow. Modern tools often look different on the surface, but many of their “best” moments are direct echoes of his core concepts.

Across categories, the same foundations keep reappearing: links (to connect ideas), structure (outlines, blocks, fields), search (to retrieve), permissions (to share safely), and history (versioning and audit trails).

The common failure isn’t missing features—it’s fragmentation.

Work gets split across apps, and the context leaks away: a decision in chat, the rationale in a doc, the action in a task, the evidence in a file. You can link them, but you still spend time reconstructing “what’s going on.”

Think in four verbs: capture → connect → coordinate → decide. If your tools support all four with minimal context-switching—and preserve links, structure, and history along the way—you’re closer to Engelbart’s real contribution than any single app could ever be.

This is also a useful lens for newer “vibe-coding” tools: when an AI helps you ship software, the win isn’t just generating code—it’s keeping intent, decisions, and implementation connected. Platforms like Koder.ai try to operationalize that idea by letting teams build web, backend, and mobile apps through chat while maintaining a clear path from requirements to working features.

Engelbart’s core promise wasn’t a specific app—it was a way of working: structure information, connect it, and make collaboration explicit.

You can adopt a lot of that in whatever you already use (Docs, Word, Notion, Confluence, Slack, email).

Start documents as an outline, not a “perfect” narrative. Use headings, bullets, and short blocks that can be rearranged.

This makes meetings faster (everyone can point to the same section) and editing less intimidating (people can adjust one block without rewriting the whole page).

When you write a claim, add the link next to it. When you make a decision, record why and link to the discussion or evidence.

A small decision log prevents endless re-litigation.

Decision note format: Decision → Reason → Owner → Date → Link to evidence

Don’t let outcomes live only in chat. After a meeting, post a short summary that includes:

Assign clear ownership for each doc (“DRI” or “Editor”) so someone is accountable for keeping it coherent.

When making significant edits, add a short change summary at the top (or in a comment): What changed + why + what you need from others. This is the human version of version control.

Use consistent naming: TEAM — Project — Doc — YYYY-MM-DD.

Use templates for recurring work: meeting notes, project briefs, retro notes, decision logs.

Engelbart didn’t single‑handedly invent the mouse, hypertext, or collaboration.

Earlier ideas existed: Vannevar Bush described linked knowledge in “As We May Think,” and others built pointing devices before the modern mouse. What Engelbart truly pushed forward was the system-level direction: integrating pointing, links, structured documents, and teamwork into one coherent environment—with the explicit goal of improving how groups think and solve problems.

The 1960s version of this future was expensive and fragile. Interactive computing required costly time‑sharing machines, specialized displays, and custom input hardware.

Networks were limited, storage was scarce, and software had to be hand-crafted.

Just as important: many organizations weren’t ready. Engelbart’s approach asked teams to change habits, adopt shared conventions, and invest in training—costs that are easy to cut when budgets tighten. Later, the industry’s shift toward personal computers favored simpler, standalone apps over deeply integrated collaborative systems.

NLS rewarded users who learned its structured methods (and, famously, advanced input techniques). That meant “computer literacy” wasn’t optional.

The collaboration piece also required psychological buy‑in: working in shared spaces, exposing drafts, and coordinating decisions openly—hard in competitive or siloed cultures.

For more context on how these ideas echo in modern tools, see /blog/how-his-ideas-show-up-in-todays-productivity-software.

Engelbart argued that computers should amplify human thinking and teamwork, not replace it. “Augmentation” means making it easier to:

If a tool helps you understand, decide, and collaborate faster (not just execute), it fits his goal.

Automation does work instead of you (good for repetitive, well-defined tasks). Augmentation helps you do better thinking on messy, ambiguous work.

A practical rule: if the task needs judgment (tradeoffs, unclear goals, evolving context), prioritize tools and workflows that improve clarity, navigation, and shared understanding—not just speed.

Bootstrapping is the idea that improvements should compound: better tools make you more capable, and that capability helps you improve your tools and methods again.

To apply it:

Small process upgrades become a flywheel.

NLS (the oN-Line System) was an early interactive knowledge workspace for creating, organizing, and connecting information while working.

It combined ideas many tools split today:

Think “docs + wiki + collaboration” in one environment.

In a screen-based workspace, pointing reduces translation overhead. Instead of remembering commands like “go to line 237,” you can point to what you mean and act.

Practical takeaway: when choosing tools, favor interfaces that let you quickly select, rearrange, and navigate content (multi-pane views, good keyboard shortcuts, precise selection). Speed comes from reduced friction, not just faster typing.

Hypertext turns information into a network you can navigate, not a single linear document.

To make it useful in daily work:

Good links prevent “why are we doing this?” from becoming a recurring meeting.

Structured writing treats content as movable blocks (headings, bullets, nested sections) rather than one long page.

A simple workflow:

This makes collaboration easier because people can own and comment on specific sections.

Engelbart’s core insight was that complex work needs shared context, not just shared files.

Practical habits that create shared context:

Tools enable this, but team norms make it stick.

Real-time co-editing is valuable because it speeds up alignment, not typing.

To avoid chaos:

Live editing works best when intent is visible and decisions get captured.

A few constraints slowed adoption:

Also, Engelbart didn’t “invent everything”; his impact was system-level integration (pointing + links + structure + teamwork) aimed at improving how groups solve problems. For a modern mapping of those ideas, see /blog/how-his-ideas-show-up-in-todays-productivity-software.