Aug 30, 2025·8 min

Edgar F. Codd’s Relational Model: Why SQL Won Business

Learn how Edgar F. Codd’s relational model turned data into tables, keys, and rules—paving the way for SQL databases that power business apps.

Learn how Edgar F. Codd’s relational model turned data into tables, keys, and rules—paving the way for SQL databases that power business apps.

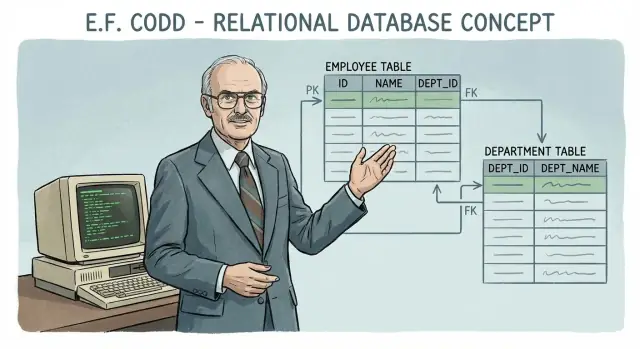

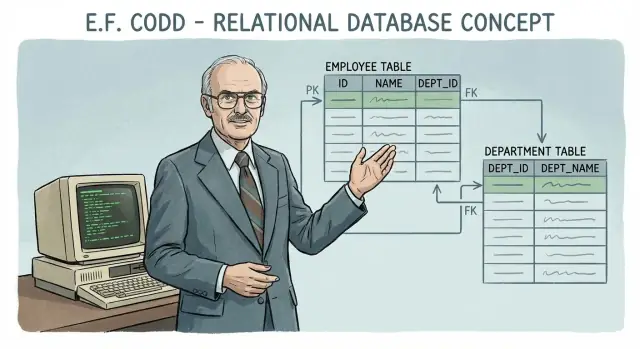

At its simplest, the relational model stores information as a set of tables (what Codd called “relations”) that can be linked through shared values.

A table is a tidy grid:

Businesses don’t keep data in isolation. A sale involves a customer, a product, a price, a salesperson, and a date—each changing at different speeds and owned by different teams. Early systems often stored these details in tightly coupled, hard-to-change structures. That made reporting slow, changes risky, and “simple questions” surprisingly expensive.

The relational model introduced a clearer approach: keep separate tables for separate concepts, then connect them when you need answers. Instead of duplicating customer details on every invoice record, you store customers once and reference them from invoices. This reduces contradictions (two spellings of the same customer) and makes updates more predictable.

By emphasizing well-defined tables and rules for connecting them, the model set a new expectation: the database should help prevent inconsistency as it grows—especially when many people and systems write to it.

Codd’s model wasn’t a query language, but it inspired one. If data lives in related tables, you need a standard way to:

That path led to SQL, which turned the model into a practical way for everyday teams to ask questions of business data and get repeatable, auditable answers.

Before the relational model, many organizations stored important information in files—often one file per application. Payroll had its own records, inventory had another, and customer service kept yet another version of “the customer.” Each system worked in isolation, and that isolation created predictable pain.

Early data processing was usually built around custom file formats and programs written for a single purpose. The structure of the data (where each field lives, how records are ordered) was tightly tied to the code that read it. That meant even small changes—adding a new field, renaming a product category, changing an address format—could require rewriting multiple programs.

Because teams couldn’t easily share a single source of truth, they copied data. Customer addresses might exist in sales files, shipping files, and billing files.

When an address changed, every copy had to be updated. If one system was missed, inconsistencies appeared: invoices went to the wrong place, shipments got delayed, and support agents saw different “facts” depending on which screen they used. Data cleanups became recurring projects instead of a one-time fix.

Business users still asked business questions—“Which customers bought product X and later returned it?”—but answering them required stitching together files never designed to work together. Teams often built one-off reporting extracts, which introduced yet more copies and more opportunities for mismatch.

The result: reporting cycles were slow, and “quick questions” became engineering work.

Organizations needed shared data that multiple applications could rely on, with fewer inconsistencies and less duplicated effort. They also needed a way to ask new questions without rebuilding the underlying storage every time. That gap set the stage for Codd’s key idea: define data in a consistent, application-independent way, so systems can evolve without breaking the truth they depend on.

Edgar F. Codd was a British computer scientist who spent much of his career at IBM, working on how organizations could store and retrieve information efficiently. In the 1960s, most “database” systems were closer to carefully managed file cabinets: data was stored in rigid, pre-defined structures, and changing those structures often meant rewriting applications. That brittleness frustrated teams as businesses grew and requirements changed.

In 1970, Codd published a paper with a long title—“A Relational Model of Data for Large Shared Data Banks”—that proposed a surprisingly simple idea: represent data as related tables, and use a formal set of operations to query and combine them.

At a high level, the paper argued that:

Codd grounded his proposal in mathematics (set theory and logic). That wasn’t academic showmanship—it gave database design a clear, testable basis. With a formal model, you can reason about whether a query is correct, whether two queries are equivalent, and how to optimize execution without changing results. For business software, that translates into fewer surprises as systems scale and evolve.

At the time, many systems relied on hierarchical or network models where developers “navigated” data along predefined paths. Codd’s approach challenged that mindset by saying the database should do the heavy lifting. Applications shouldn’t have to know the storage layout; they should describe the desired result, and the database should figure out an efficient way to produce it.

That separation of concerns set the stage for SQL and for databases that could survive years of changing product requirements.

Codd’s relational model starts with a simple idea: store facts in relations—what most people recognize as tables—but treat them as a precise way to describe data, not as “smart spreadsheets.” A relation is a set of statements about things your business cares about: customers, invoices, payments, products, shipments.

A relation represents one kind of fact pattern. For example, an Orders relation might capture “an order has an ID, a date, a customer, and a total.” The key point is that each relation has a clearly defined meaning, and each column is part of that meaning.

A row (Codd called it a tuple) is one specific instance of that fact: one particular order. In the relational model, rows don’t have an inherent “position.” Row 5 isn’t special—what matters is the values and the rules that define them.

A column (an attribute) is one specific property in the relation: OrderDate, CustomerID, TotalAmount. Columns aren’t just labels; they define what kind of value is allowed.

A domain is the allowed set of values for an attribute—like dates for OrderDate, positive numbers for TotalAmount, or a controlled code list for Status (e.g., Pending, Paid, Refunded). Domains reduce ambiguity and prevent subtle errors like mixing “12/10/25” formats or storing “N/A” inside numeric fields.

“Relational” refers to how facts can be connected across relations (like customers to orders), enabling common business tasks—billing, reporting, auditing, customer support—without duplicating the same information everywhere.

Tables are useful on their own, but business data only makes sense when you can reliably connect facts: which customer placed which order, which items were in it, and how much was charged. Keys are the mechanism that makes those connections dependable.

A primary key is a column (or set of columns) whose value uniquely identifies a row. Think of it as a row’s “name tag.” The important part is stability: names, emails, and addresses can change, but an internal ID should not.

A good primary key prevents duplicate or ambiguous records. If two customers share the same name, the primary key still distinguishes them.

A foreign key is a column that stores the primary key from another table. This is how relationships are represented without copying all the data.

For example, you might model sales like this:

Foreign key constraints act like guardrails. They prevent:

In practical terms, keys and constraints let teams trust reports and workflows. When the database enforces relationships, fewer bugs slip into billing, fulfillment, and customer support—because the data can’t quietly drift into impossible states.

Normalization is the relational model’s way of keeping data from drifting into contradictions as it grows. When the same fact is stored in multiple places, it’s easy to update one copy and forget another. That’s how businesses end up with invoices going to the wrong address, reports that don’t match, or a customer marked “inactive” in one screen and “active” in another.

At a practical level, normalization reduces common problems:

It also avoids insert anomalies (you can’t add a new customer until they place an order) and delete anomalies (deleting the last order accidentally deletes the only copy of the customer’s details).

You don’t need heavy theory to use the idea well:

First Normal Form (1NF): keep each field atomic. If a customer has multiple phone numbers, don’t cram them into one cell; use a separate table (or separate rows) so each value can be searched and updated cleanly.

Second Normal Form (2NF): if a table’s identity depends on more than one column (a composite key), make sure non-key details depend on the whole thing. An order line should store item quantity and price for that line, not customer address.

Third Normal Form (3NF): remove “side facts” that belong elsewhere. If a table stores CustomerId and also CustomerCity, the city should typically live in the customer table, not be copied into every order.

More normalization usually means more tables and more joins. That improves consistency, but it can complicate reporting and sometimes affects performance. Many teams aim for 3NF for core entities (customers, products, invoices), then selectively denormalize for read-heavy dashboards—while keeping one authoritative source of truth enforced by primary key / foreign key relationships.

Relational algebra is the “math” behind the relational model: a small set of precise operations for transforming one set of rows (a table) into another set of rows.

That precision matters. If the rules are clear, then query results are clear. You can predict what happens when you filter, reshape, or combine data—without relying on undocumented behaviors or manual navigation.

Relational algebra defines building blocks that can be composed. Three of the most important are:

Select: pick the rows you want.

Example idea: “Only orders from last month” or “Only customers in France.” You keep the same columns, but reduce the number of rows.

Project: pick the columns you want.

Example idea: “Show customer name and email.” You keep the same rows (logically), but drop columns you don’t need.

Join: combine related facts from different tables.

Example idea: “Attach customer details to each order,” using a shared identifier (like customer_id). The output is a new table where each row brings together fields that were stored separately.

Business data is naturally split across subjects: customers, orders, invoices, products, payments. That separation keeps each fact stored once (which helps avoid mismatches), but it also means answers often require recombining those facts.

Joins are the formal way to do that recombination while preserving meaning. Instead of copying customer names into every order row (and later fixing spelling changes everywhere), you store customers once and join when you need a report.

Because relational algebra is defined as operations on sets of rows, the expected outcome of each step is well-scoped:

This is the conceptual backbone that later made SQL practical: queries become sequences of well-defined transformations, not ad-hoc data fetching.

Codd’s relational model described what data means (relations, keys, and operations) without prescribing a friendly way for people to use it day to day. SQL filled that gap: it turned relational ideas into a practical, readable language that analysts, developers, and database products could share.

SQL is inspired by relational algebra, but it isn’t a perfect implementation of Codd’s original theory.

One key difference is how SQL treats missing or unknown values. Classic relational theory is based on two-valued logic (true/false), while SQL introduces NULL, which leads to three-valued logic (true/false/unknown). Another difference: relational theory works with sets (no duplicates), but SQL tables often allow duplicate rows unless you explicitly prevent them.

Despite these differences, SQL kept the core promise: you describe the result you want (a declarative query), and the database figures out the steps.

Codd published his foundational paper in 1970. In the 1970s, IBM built early prototypes (notably System R) that demonstrated a relational database could perform well enough for real workloads and that a high-level query language could be compiled into efficient execution plans.

In parallel, academic and commercial efforts pushed SQL forward. By the late 1980s, SQL standardization (ANSI/ISO) made it possible for vendors to converge on a common language—even if each product kept its own extensions.

SQL lowered the cost of asking questions. Instead of writing custom programs for every report, teams could express questions directly:

GROUP BYFor business software, SQL’s combination of joins and aggregation was a breakthrough. A finance team could reconcile invoices to payments; a product team could analyze conversion funnels; an operations team could monitor inventory and fulfillment—all by querying the same shared, structured data model.

That usability is a big reason the relational model escaped the research world and became a daily tool.

Business systems live or die on trust. It’s not enough for a database to “store data”—it must preserve correct balances, accurate inventory counts, and a believable audit trail even when many people use the system at once.

A transaction groups a set of changes into a single business operation. Think: “transfer $100,” “ship an order,” or “post a payroll run.” Each of these touches multiple tables and multiple rows.

The key idea is all-or-nothing behavior:

That’s how you avoid situations like money leaving one account but never arriving in the other, or inventory being reduced without an order being recorded.

ACID is shorthand for the guarantees businesses rely on:

Constraints (like primary keys, foreign keys, and checks) prevent invalid states from being recorded. Transactions ensure that related updates across tables arrive together.

In practice: an order is saved, its line items are saved, inventory is decremented, and an entry is written to an audit log—either all of it happens, or none of it does. That combination is what lets SQL databases support serious business software at scale.

SQL databases didn’t “win” because they were trendy—they matched how most organizations already think and work. A company is full of repeating, structured things: customers, invoices, products, payments, employees. Each has a clear set of attributes, and they relate to each other in predictable ways. The relational model maps neatly to that reality: a customer can have many orders, an order has line items, payments reconcile to invoices.

Business processes are built around consistency and traceability. When finance asks, “Which invoices are unpaid?” or support asks, “What plan is this customer on?”, the answers should be the same no matter which tool or team is asking. Relational databases are designed to keep facts stored once and referenced everywhere, reducing contradictions that lead to costly rework.

As SQL became widespread, an ecosystem formed around it: reporting tools, BI dashboards, ETL pipelines, connectors, and training. That compatibility lowered the cost of adoption. If your data lives in a relational database, it’s usually straightforward to plug into common reporting and analytics workflows without custom glue code.

Applications evolve quickly—new features, new UIs, new integrations. A well-designed schema acts like a durable contract: even as services and screens change, core tables and relationships keep the meaning of the data stable. That stability is a big reason SQL databases became the dependable center of business software.

Schemas don’t just organize data—they clarify roles. Teams can agree on what a “Customer” is, which fields are required, and how records connect. With primary keys and foreign keys, responsibilities become explicit: who creates records, who can update them, and what must remain consistent across the business.

Relational databases earned their place by being predictable and safe, but they’re not the best fit for every workload. Many critiques of SQL systems are really critiques of using one tool for every job.

A relational schema is a contract: tables, columns, types, and constraints define what “valid data” means. That’s great for shared understanding, but it can slow teams when the product is still evolving.

If you’re shipping new fields weekly, coordinating migrations, backfills, and deployments can become a bottleneck. Even with good tooling, schema changes require planning—especially when tables are large or systems must stay online 24/7.

“NoSQL” wasn’t a rejection of the relational idea so much as a response to specific pain points:

Many of these systems traded away strict consistency or rich joins to gain speed, flexibility, or distribution.

Most modern stacks are polyglot: a relational database for core business records, plus an event stream, a search index, a cache, or a document store for content and analytics. The relational model remains the source of truth, while other stores serve read-heavy or specialized queries.

When choosing, focus on:

A good default is SQL for core data, then add alternatives only where the relational model is clearly the limiting factor.

Codd’s relational model isn’t just history—it’s a set of habits that make business data easier to trust, change, and report on. Even if your app uses a mix of storage systems, the relational way of thinking is still a strong default for “systems of record” (orders, invoices, customers, inventory).

Start by modeling the real-world nouns your business cares about as tables (Customers, Orders, Payments), then use relationships to connect them.

A few rules that prevent most pain later:

If you’re turning these principles into an actual product, it helps to have tooling that keeps schema intent and application code aligned. For example, Koder.ai can generate a React + Go + PostgreSQL app from a chat prompt, which makes it easy to prototype a normalized schema (tables, keys, relationships) and iterate—while still keeping the database as the source of truth and allowing source code export when you’re ready to take full control.

If your data needs strong correctness guarantees, ask:

If the answer is “yes” often, a relational database is usually the simplest path.

“SQL can’t scale” is too broad. SQL systems scale in many ways (indexes, caching, read replicas, sharding when needed). Most teams hit modeling and query issues long before they hit true database limits.

“Normalization makes everything slow” is also incomplete. Normalization reduces anomalies; performance is managed with indexes, query design, and selective denormalization when measurements justify it.

Codd gave teams a shared contract: data arranged in related tables, manipulated with well-defined operations, and protected by constraints. That contract is why everyday software can evolve for years without losing the ability to answer basic questions like “what happened, when, and why?”

The relational model stores data as tables (relations) with:

Its key benefit is that separate tables can be linked through shared identifiers, so you can keep each fact in one place and recombine it for reports and workflows.

File-based systems tied data layout tightly to application code. That created practical problems:

Relational databases decoupled data definition from any single app and made cross-cutting queries routine.

A primary key (PK) uniquely identifies each row in a table and should remain stable over time.

Practical guidance:

customer_id) over mutable fields like email.A foreign key (FK) is a column whose values must match an existing primary key in another table. It’s how you represent relationships without copying entire records.

Example pattern:

orders.customer_id references customers.customer_idWith FK constraints enabled, the database can prevent:

Normalization reduces inconsistency by storing each fact once (or as close to once as practical). It helps prevent:

A common target is , then selective denormalization only when measured needs justify it.

A good 1NF rule: one field, one value.

If you find yourself adding columns like phone1, phone2, phone3, split them into a related table instead:

customer_phones(customer_id, phone_number, type)This makes searching, validating, and updating phone numbers straightforward and avoids awkward “missing column” cases.

Relational algebra defines the core operations behind relational queries:

You don’t need to write relational algebra day to day, but understanding these concepts helps you reason about SQL results and avoid accidental data duplication in joins.

SQL made relational ideas usable by providing a declarative way to ask questions: you describe the result, and the database chooses an execution plan.

Key practical wins:

GROUP BY)Even though SQL isn’t a “perfect” implementation of Codd’s theory, it preserved the core workflow: reliable querying over related tables.

SQL differs from the “pure” relational model in a few important ways:

NULL introduces three-valued logic (true/false/unknown), which affects filters and joins.Practically, this means you should be deliberate about handling and enforce uniqueness where it matters.

Use a relational database when you need strong correctness for shared business records.

A practical checklist:

Consider adding NoSQL or specialized stores when you specifically need flexible shapes, high-scale distribution patterns, or specialized queries (search/graph)—but keep a clear system of record.

NULL