Aug 09, 2025·7 min

Environment configuration patterns for dev, staging, prod

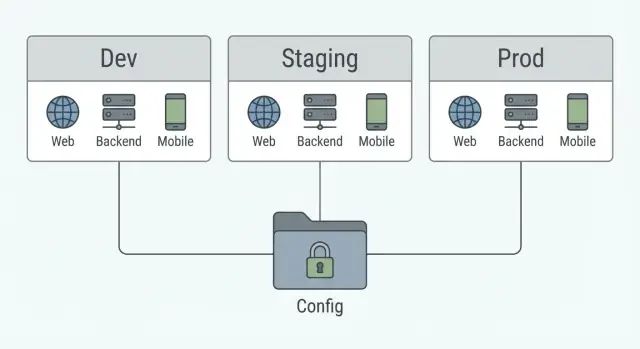

Environment configuration patterns that keep URLs, keys, and feature flags out of code across web, backend, and mobile in dev, staging, and prod.

Why hardcoded config keeps causing problems

Hardcoded config feels fine on day one. Then you need a staging environment, a second API, or a quick feature switch, and the “simple” change turns into a release risk. The fix is straightforward: keep environment values out of source files and put them in a predictable setup.

The usual troublemakers are easy to spot:

- API base URLs baked into the app (calling prod while you test, or calling dev after release)

- API keys committed to the repo (leaks, surprise bills, emergency rotations)

- Feature toggles written as constants (you have to ship code to turn something off)

- Analytics and error reporting IDs hardcoded (data ends up in the wrong place)

“Just change it for prod” creates a habit of last-minute edits. Those edits often skip review, tests, and repeatability. One person changes a URL, another changes a key, and now you can’t answer a basic question: what exact config shipped with this build?

A common scenario: you build a new mobile version against staging, then someone flips the URL to prod right before release. The backend changes again the next day, and you need to roll back. If the URL is hardcoded, rollback means another app update. Users wait, and support tickets pile up.

The goal here is a simple scheme that works across a web app, a Go backend, and a Flutter mobile app:

- clear rules for what belongs in code vs config

- safe defaults for dev, staging, and prod

- feature switches that can change without a full rebuild

- secrets handled outside the codebase, with room to rotate them

What really changes between dev, staging, and prod

Dev, staging, and prod should feel like the same app running in three different places. The point is to change values, not behavior.

What should change is anything tied to where the app runs or who is using it: base URLs and hostnames, credentials, sandbox vs real integrations, and safety controls like logging level or stricter security settings in prod.

What should stay the same is the logic and the contract between parts. API routes, request and response shapes, feature names, and core business rules shouldn’t vary by environment. If staging behaves differently, it stops being a reliable rehearsal for production.

A practical rule for “new environment” vs “new config value”: create a new environment only when you need an isolated system (separate data, access, and risk). If you just need different endpoints or different numbers, add a config value instead.

Example: you want to test a new search provider. If it’s safe to enable it for a small group, keep one staging environment and add a feature flag. If it requires a separate database and strict access controls, that’s when a new environment makes sense.

A practical config model you can reuse everywhere

A good setup does one thing well: it makes it hard to accidentally ship a dev URL, a test key, or an unfinished feature.

Use the same three layers for every app (web, backend, mobile):

- Defaults: safe values that work in most places.

- Environment overrides: what changes for dev, staging, prod.

- Secrets: sensitive values that never live in the repo.

To avoid confusion, pick one source of truth per app and stick to it. For example, the backend reads from environment variables at startup, the web app reads from build-time variables or a small runtime config file, and the mobile app reads from a small environment file selected at build time. Consistency inside each app matters more than forcing the exact same mechanism everywhere.

A simple, reusable scheme looks like this:

- Defaults live in code as non-sensitive constants (timeouts, page size, retry counts).

- Overrides live in env-specific files or environment variables (API base URL, analytics on/off).

- Secrets live in a secret store and get injected during deploy/build (JWT secret, database password, third-party API keys).

Naming that people can understand

Give every config item a clear name that answers three questions: what it is, where it applies, and what type it is.

A practical convention:

- Prefix by app: WEB_, API_, MOBILE_

- Use ALL_CAPS with underscores

- Group by purpose: API_BASE_URL, AUTH_JWT_SECRET, FEATURES_NEW_CHECKOUT

- Keep booleans explicit: FEATURES_SEARCH_ENABLED=true

This way, nobody has to guess whether “BASE_URL” is for the React app, the Go service, or the Flutter app.

Step by step: web app config (React) without hardcoding

React code runs in the user’s browser, so anything you ship can be read. The goal is simple: keep secrets on the server, and let the browser read only “safe” settings like an API base URL, app name, or a non-sensitive feature toggle.

1) Decide what is build-time vs runtime

Build-time config is injected when you build the bundle. It’s fine for values that rarely change and are safe to expose.

Runtime config is loaded when the app starts (for example, from a small JSON file served with the app, or an injected global). It’s better for values you may want to change after deploy, like switching an API base URL between environments.

A simple rule: if changing it shouldn’t require rebuilding the UI, make it runtime.

2) Store the API base URL without committing it

Keep a local file for developers (not committed) and set real values in your deploy pipeline.

- Local dev: use

.env.local(gitignored) with something likeVITE_API_BASE_URL=http://localhost:8080 - CI/CD: set

VITE_API_BASE_URLas an environment variable in the build job, or put it into a runtime config file created during deploy

Runtime example (served next to your app):

{ "apiBaseUrl": "https://api.staging.example.com", "features": { "newCheckout": false } }

Then load it once at startup and keep it in a single place:

export async function loadConfig() {

const res = await fetch('/config.json', { cache: 'no-store' });

return res.json();

}

3) Expose only safe values to the browser

Treat anything in React env vars as public. Don’t put passwords, private API keys, or database URLs in the web app.

Safe examples: API base URL, Sentry DSN (public), build version, and simple feature flags.

Step by step: backend config (Go) you can validate

Backend config stays safer when it’s typed, loaded from environment variables, and validated before the server starts accepting traffic.

Start by deciding what the backend needs to run, and make those values explicit. Typical “must have” values are:

APP_ENV(dev, staging, prod)HTTP_ADDR(for example:8080)DATABASE_URL(Postgres DSN)PUBLIC_BASE_URL(used for callbacks and links)API_KEY(for a third party service)

Then load them into a struct and fail fast if anything is missing or malformed. That way you find problems in seconds, not after a partial deploy.

package config

import (

"errors"

"net/url"

"os"

"strings"

)

type Config struct {

Env string

HTTPAddr string

DatabaseURL string

PublicBaseURL string

APIKey string

}

func Load() (Config, error) {

c := Config{

Env: mustGet("APP_ENV"),

HTTPAddr: getDefault("HTTP_ADDR", ":8080"),

DatabaseURL: mustGet("DATABASE_URL"),

PublicBaseURL: mustGet("PUBLIC_BASE_URL"),

APIKey: mustGet("API_KEY"),

}

return c, c.Validate()

}

func (c Config) Validate() error {

if c.Env != "dev" && c.Env != "staging" && c.Env != "prod" {

return errors.New("APP_ENV must be dev, staging, or prod")

}

if _, err := url.ParseRequestURI(c.PublicBaseURL); err != nil {

return errors.New("PUBLIC_BASE_URL must be a valid URL")

}

if !strings.HasPrefix(c.DatabaseURL, "postgres://") {

return errors.New("DATABASE_URL must start with postgres://")

}

return nil

}

func mustGet(k string) string {

v, ok := os.LookupEnv(k)

if !ok || strings.TrimSpace(v) == "" {

panic("missing env var: " + k)

}

return v

}

func getDefault(k, def string) string {

if v, ok := os.LookupEnv(k); ok && strings.TrimSpace(v) != "" {

return v

}

return def

}

This keeps database DSNs, API keys, and callback URLs out of code and out of git. In hosted setups, you inject these env vars per environment so dev, staging, and prod can differ without changing a single line.

Step by step: mobile config (Flutter) that stays flexible

Stop hardcoding settings

Prototype quickly, then keep URLs, flags, and secrets out of your source files.

Flutter apps usually need two layers of config: build-time flavors (what you ship) and runtime settings (what the app can change without a new release). Keeping those separate stops “just one quick URL change” from turning into an emergency rebuild.

1) Use flavors for identity, not endpoints

Create three flavors: dev, staging, prod. Flavors should control things that must be fixed at build time, like app name, bundle id, signing, analytics project, and whether debug tools are enabled.

Then pass only non-sensitive defaults with --dart-define (or your CI) so you never hardcode them in code:

ENV=stagingDEFAULT_API_BASE=https://api-staging.example.comCONFIG_URL=https://config.example.com/mobile.json

In Dart, read them with String.fromEnvironment and build a simple AppConfig object once at startup.

2) Put URLs and switches in a fetched config

If you want to avoid rebuilding for small endpoint changes, don’t treat the API base URL as a constant. Fetch a tiny config file on app launch (and cache it). The flavor sets only where to fetch config from.

A practical split:

- Flavor (build-time): app identity, default config URL, crash reporting project

- Remote config (runtime): API base URL, feature flags, rollout percentages, maintenance mode

- Secrets: never shipped in the app (mobile binaries can be inspected)

If you move your backend, you update the remote config to point to the new base URL. Existing users pick it up on next launch, with a safe fallback to the last cached value.

Feature flags and switches that do not turn into chaos

Feature flags are useful for gradual rollouts, A-B tests, quick kill switches, and testing risky changes in staging before turning them on in prod. They’re not a replacement for security controls. If a flag guards something that must be protected, it’s not a flag - it’s an auth rule.

Treat every flag like an API: clear name, an owner, and an end date.

Naming that makes intent obvious

Use names that tell you what happens when the flag is ON, and what part of the product it touches. A simple scheme:

feature.checkout_new_ui_enabled(customer-facing feature)ops.payments_kill_switch(emergency off switch)exp.search_rerank_v2(experiment)release.api_v3_rollout_pct(gradual rollout)debug.show_network_logs(diagnostics)

Prefer positive booleans (..._enabled) over double negatives. Keep a stable prefix so you can search and audit flags.

Defaults, guardrails, and cleanup

Start with safe defaults: if the flag service is down, your app should behave like the stable version.

A realistic pattern: ship a new endpoint in the backend, keep the old one running, and use release.api_v3_rollout_pct to slowly move traffic. If errors spike, flip it back without a hotfix.

To prevent flag pileups, keep a few rules:

- Every flag has an owner and an “remove by” date

- Remove flags within 1-2 releases after full rollout

- Log flag values in key flows for debugging

- Review flags monthly like you review dependencies

Secrets: storage, access, and rotation basics

Avoid emergency mobile rebuilds

Generate a Flutter app with flavors and a remote config URL for flexible endpoints.

A “secret” is anything that would cause damage if leaked. Think API tokens, database passwords, OAuth client secrets, signing keys (JWT), webhook secrets, and private certificates. Not secrets: API base URLs, build numbers, feature flags, or public analytics IDs.

Separate secrets from the rest of your settings. Developers should be able to change safe config freely, while secrets get injected only at runtime and only where needed.

Where secrets should live (by environment)

In dev, keep secrets local and disposable. Use a .env file or your OS keychain and make it easy to reset. Never commit it.

In staging and prod, secrets should live in a dedicated secrets store, not in your code repo, not in chat logs, and not baked into mobile apps.

- Web (React): don’t put secrets in the browser. If the client needs a token, use a short-lived token issued by your backend.

- Backend (Go): load secrets from environment variables or a secrets manager at startup, and keep them in memory only.

- Mobile (Flutter): treat the app as public. Any “secret” in the app can be extracted, so use backend-issued tokens and device secure storage only for user session data.

Rotation basics (without breaking production)

Rotation fails when you swap a key and forget old clients still use it. Plan an overlap window.

- Support two valid secrets at once (active + previous) for a short window.

- Roll out the new secret first, then switch the “active” pointer.

- Monitor auth failures, then remove the old secret after the window ends.

- Log secret versions (not secret values) to debug safely.

This overlap approach works for API keys, webhook secrets, and signing keys. It avoids surprise outages.

Example rollout: changing API URLs without breaking users

You have a staging API and a new production API. The goal is to move traffic over in phases, with a quick way back if anything looks off. This is easier when the app reads the API base URL from config, not from code.

Treat the API URL as a deploy-time value everywhere. In the web app (React), it’s often a build-time value or runtime config file. In mobile (Flutter), it’s typically a flavor plus remote config. In the backend (Go), it’s a runtime env var. The important part is consistency: the code uses one variable name (for example, API_BASE_URL) and never embeds the URL in components, services, or screens.

A safe phased rollout can look like this:

- Deploy the prod API and keep it “dark” (internal traffic only) while staging stays the default.

- Switch backend dependencies first (if your backend calls other services), using env vars and a quick restart.

- Move web traffic over in a small slice (or only internal accounts).

- Release the mobile app with the new setup, but keep a server-controlled flag to delay switching until you’re ready.

- Increase traffic gradually and keep a rollback ready.

Verification is mostly about catching mismatches early. Before real users hit the change, confirm health endpoints respond, auth flows work, and the same test account can complete one key journey end-to-end.

Quick checklist before you ship

Most production config bugs are boring: a staging value left in place, a flag default flipped, or an API key missing in one region. A quick pass catches most of them.

Before you deploy, confirm three things match the target environment: endpoints, secrets, and defaults.

- Base URLs point to the right place (API, auth, CDN, payments). Check web, backend, and mobile separately.

- No test keys in production, and no production keys in dev or staging. Also confirm key names match what the app expects.

- Feature flags have safe defaults. Anything risky should default to off and be enabled intentionally.

- Build and release settings match (bundle ID/package name, custom domain, CORS origins, OAuth redirect URLs).

- Observability is configured (logs, error reporting, tracing) and set to the correct environment label.

Then do a fast smoke test. Pick one real user flow and run it end to end, using a fresh install or clean browser profile so you don’t rely on cached tokens.

- Open the app and confirm it loads without console errors.

- Sign in and hit one API call that requires auth (profile, settings, or a simple data list).

- Trigger one controlled failure (bad input or offline mode) and confirm you see a friendly message, not a blank screen.

- Check logs and error reporting: one test error should appear under the right environment within a few minutes.

A practical habit: treat staging like production with different values. That means the same config schema, the same validation rules, and the same deployment shape.

Common mistakes that lead to outages

Host across environments

Move from staging to prod with clearer inputs and fewer last-minute edits.

Most configuration outages aren’t exotic. They’re simple mistakes that slip through because config is spread across files, build steps, and dashboards, and nobody can answer: “What values will this app use right now?” A good setup makes that question easy.

Mixing build-time and runtime settings

A common trap is putting runtime values into build-time places. Baking an API base URL into a React build means you must rebuild for every environment. Then someone deploys the wrong artifact and production points to staging.

A safer rule: only bake in values that truly never change after release (like an app version). Keep environment details (API URLs, feature switches, analytics endpoints) runtime where possible, and make the source of truth obvious.

Shipping dev endpoints or test keys

This happens when defaults are “helpful” but unsafe. A mobile app might default to a dev API if it can’t read config, or a backend might fall back to a local database if an env var is missing. That turns a small config mistake into a full outage.

Two habits help:

- Fail closed: if a required value is missing, crash early with a clear error.

- Make production the hardest environment to misconfigure: no dev defaults, no test keys accepted, no debug endpoints enabled.

A realistic example: a release goes out Friday night, and the production build accidentally contains a staging payment key. Everything “works” until charges silently fail. The fix isn’t a new payment library. It’s validation that rejects non-production keys in production.

Letting staging drift away from production

Staging that doesn’t match production gives false confidence. Different database settings, missing background jobs, or extra feature flags make bugs appear only after launch.

Keep staging close by mirroring the same config schema, the same validation rules, and the same deployment shape. Only the values should differ, not the structure.

Next steps: make config boring, repeatable, and safe

The goal isn’t fancy tooling. It’s boring consistency: the same names, the same types, the same rules across dev, staging, and prod. When config is predictable, releases stop feeling risky.

Start by writing down a clear config contract in one place. Keep it short but specific: every key name, its type (string, number, boolean), where it’s allowed to come from (env var, remote config, build-time), and its default. Add notes for values that must never be set in a client app (like private API keys). Treat this contract like an API: changes need review.

Then make mistakes fail early. The best time to discover a missing API base URL is in CI, not after deployment. Add automated validation that loads config the same way your app does and checks:

- required values are present (no empty strings)

- types are correct (no "true" vs true bugs)

- prod-only rules pass (for example, HTTPS required)

- feature flags have known names (no typos)

- secrets are not checked into the repo

Finally, make it easy to recover when a config change is wrong. Snapshot what’s running, change one thing at a time, verify quickly, and keep a rollback path.

If you’re building and deploying with a platform like Koder.ai (koder.ai), the same rules apply: treat environment values as inputs to build and hosting, keep secrets out of exported source, and validate config before you ship. That consistency is what makes redeploys and rollbacks feel routine.

When config is documented, validated, and reversible, it stops being a source of outages and turns into a normal part of shipping.