Sep 21, 2025·8 min

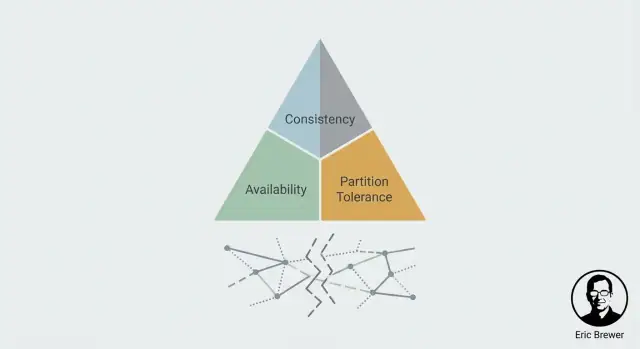

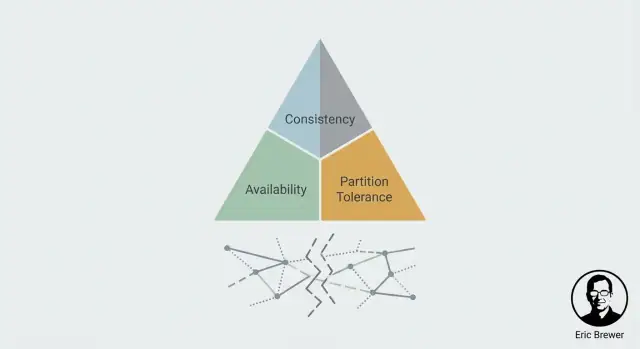

Eric Brewer’s CAP Thinking: Why Distributed Systems Trade Off

Learn Eric Brewer’s CAP theorem as a practical mental model: how consistency, availability, and partitions shape distributed system decisions.

Learn Eric Brewer’s CAP theorem as a practical mental model: how consistency, availability, and partitions shape distributed system decisions.

When you store the same data on more than one machine, you gain speed and fault tolerance—but you also inherit a new problem: disagreement. Two servers can receive different updates, messages can arrive late or not at all, and users might read different answers depending on which replica they hit. CAP became popular because it gives engineers a clean way to talk about that messy reality without hand-waving.

Eric Brewer, a computer scientist and co-founder of Inktomi, introduced the core idea in 2000 as a practical statement about replicated systems under failure. It spread quickly because it matched what teams were already experiencing in production: distributed systems don’t just fail by going down; they fail by splitting.

CAP is most useful when things go wrong—especially when the network doesn’t behave. On a healthy day, many systems can look both consistent and available enough. The pressure test is when machines can’t reliably communicate and you must decide what to do with reads and writes while the system is divided.

That framing is why CAP became a go-to mental model: it doesn’t argue about best practices; it forces a concrete question—what will we sacrifice during a split?

By the end of this article, you should be able to:

CAP endures because it turns vague “distributed is hard” talk into a decision you can make—and defend.

A distributed system is, in plain terms, many computers trying to act like one. You might have several servers in different racks, regions, or cloud zones, but to the user it’s “the app” or “the database.”

To make that shared system work at real-world scale, we usually replicate: we keep multiple copies of the same data on different machines.

Replication is popular for three practical reasons:

So far, replication sounds like a straightforward win. The catch is that replication creates a new job: keeping all copies in agreement.

If every replica could always talk to every other replica instantly, they could coordinate updates and stay aligned. But real networks aren’t perfect. Messages can be delayed, dropped, or routed around failures.

When communication is healthy, replicas can usually exchange updates and converge on the same state. But when communication breaks (even temporarily), you can end up with two valid-looking versions of “the truth.”

For example, a user changes their shipping address. Replica A receives the update, replica B doesn’t. Now the system has to answer a seemingly simple question: what is the current address?

This is the difference between:

CAP thinking starts exactly here: once replication exists, disagreement under communication failure isn’t an edge case—it’s the central design problem.

CAP is a mental model for what users actually feel when a system is spread across multiple machines (often in multiple locations). It doesn’t describe “good” or “bad” systems—just the tension you must manage.

Consistency is about agreement. If you update something, will the next read (from anywhere) reflect that update?

From a user’s point of view, it’s the difference between “I just changed it, and everyone sees the same new value” versus “some people still see the old value for a while.”

Availability means the system responds to requests—reads and writes—with a success result. Not “the fastest possible,” but “it doesn’t refuse to serve you.”

During trouble (a server down, a network hiccup), an available system keeps accepting requests, even if it has to answer with data that might be slightly out of date.

A partition is when the network splits: machines are running, but messages between some of them can’t get through (or arrive too late to be useful). In distributed systems, you can’t treat this as impossible—you have to define behavior when it happens.

Imagine two retail shops that both sell the same product and share “1 inventory count.” A customer buys the last item in Shop A, so Shop A writes inventory = 0. At the same time, a network partition prevents Shop B from hearing about it.

If Shop B stays available, it may sell an item it no longer has (accepting the sale while partitioned). If Shop B enforces consistency, it may refuse the sale until it can confirm the latest inventory (denying service during the split).

A “partition” isn’t just “the internet is down.” It’s any situation where parts of your system can’t reliably talk to each other—even though each part may still be running fine.

In a replicated system, nodes constantly exchange messages: writes, acknowledgements, heartbeats, leader elections, read requests. A partition is what happens when those messages stop arriving (or arrive too late), creating disagreement about reality: “Did the write happen?” “Who is the leader?” “Is node B alive?”

Communication can fail in messy, partial ways:

The important point: partitions are often degradation, not a clean on/off outage. From the application’s point of view, “slow enough” can be indistinguishable from “down.”

As you add more machines, more networks, more regions, and more moving parts, there are simply more opportunities for communication to break temporarily. Even if individual components are reliable, the overall system experiences failures because it has more dependencies and more cross-node coordination.

You don’t need to assume any exact failure rate to accept the reality: if your system runs long enough and spans enough infrastructure, partitions will happen.

Partition tolerance means your system is designed to keep operating during a split—even when nodes can’t agree or can’t confirm what the other side has seen. That forces a choice: either keep serving requests (risking inconsistency) or stop/reject some requests (preserving consistency).

Once you have replication, a partition is simply a communication break: two parts of your system can’t reliably talk to each other for a while. Replicas are still running, users are still clicking buttons, and your service is still receiving requests—but the replicas can’t agree on the latest truth.

That’s the CAP tension in one sentence: during a partition, you must choose to prioritize Consistency (C) or Availability (A). You don’t get both at the same time.

You’re saying: “I’d rather be correct than responsive.” When the system can’t confirm that a request will keep all replicas in sync, it must fail or wait.

Practical effect: some users see errors, timeouts, or “try again” messages—especially for operations that change data. This is common when you’d rather reject a payment than risk charging twice, or block a seat reservation than oversell.

You’re saying: “I’d rather respond than block.” Each side of the partition will keep accepting requests, even if it can’t coordinate.

Practical effect: users get successful responses, but the data they read may be stale, and concurrent updates can conflict. You then rely on reconciliation later (merge rules, last-write-wins, manual review, etc.).

This isn’t always a single global setting. Many products mix strategies:

The key moment is deciding—per operation—what’s worse: blocking a user now, or fixing conflicting truth later.

The slogan “pick two” is memorable, but it regularly misleads people into thinking CAP is a menu of three features where you only get to keep two forever. CAP is about what happens when the network stops cooperating: during a partition (or anything that looks like one), a distributed system must choose between returning consistent answers and staying available for every request.

In real distributed systems, partitions aren’t a setting you can disable. If your system spans machines, racks, zones, or regions, then messages can be delayed, dropped, reordered, or routed oddly. That’s a partition from the perspective of the software: nodes can’t reliably agree on what’s happening.

Even if the physical network is fine, failures elsewhere create the same effect—overloaded nodes, GC pauses, noisy neighbors, DNS hiccups, flaky load balancers. The result is the same: some parts of the system can’t talk to others well enough to coordinate.

Applications don’t experience “partition” as a neat, binary event. They experience latency spikes and timeouts. If a request times out after 200 ms, it doesn’t matter whether the packet arrived at 201 ms or never arrived at all: the app must decide what to do next. From the app’s point of view, slow communication is often indistinguishable from broken communication.

Many real systems are mostly consistent or mostly available, depending on configuration and operating conditions. Timeouts, retry policies, quorum sizes, and “read your writes” options can shift the behavior.

Under normal conditions, a database might look strongly consistent; under stress or cross-region hiccups, it may start failing requests (favoring consistency) or returning older data (favoring availability).

CAP is less about labeling products and more about understanding the trade you’re making when disagreement happens—especially when that disagreement is caused by plain old slowness.

CAP discussions often make consistency sound binary: either “perfect” or “anything goes.” Real systems offer a menu of guarantees, each with a different user experience when replicas disagree or a network link breaks.

Strong consistency (often “linearizable” behavior) means once a write is acknowledged, every later read—no matter which replica it hits—returns that write.

What it costs: during a partition or when a minority of replicas are unreachable, the system may delay or reject reads/writes to avoid showing conflicting states. Users notice this as timeouts, “try again,” or temporarily read-only behavior.

Eventual consistency promises that if no new updates happen, all replicas will converge. It does not promise that two users reading right now will see the same thing.

What users may notice: a recently updated profile photo that “reverts,” counters that lag behind, or a just-sent message that isn’t visible on another device for a short time.

You can often buy a better experience without demanding full strong consistency:

These guarantees map well to how people think (“don’t show me my own changes disappearing”) and can be easier to maintain during partial failures.

Start with user promises, not jargon:

Consistency is a product choice: define what “wrong” looks like to a user, then choose the weakest guarantee that prevents that wrongness.

Availability in CAP isn’t a bragging metric (“five nines”)—it’s a promise you make to users about what happens when the system can’t be certain.

When replicas can’t agree, you often choose between:

Users feel this as “the app works” versus “the app is correct.” Neither is universally better; the right choice depends on what “wrong” means in your product. A slightly outdated social feed is annoying. An outdated account balance can be harmful.

Two common behaviors show up during uncertainty:

This is not a purely technical call; it’s a policy decision. The product needs to define what is acceptable to show, and what must never be guessed.

Availability is rarely all-or-nothing. During a split, you might see partial availability: some regions, networks, or user groups succeed while others fail. This can be a deliberate design (keep serving where the local replica is healthy) or an accidental one (routing imbalances, uneven quorum reach).

A practical middle ground is degraded mode: continue serving safe actions while restricting risky ones. For example, allow browsing and search, but temporarily disable “transfer funds,” “change password,” or other operations where correctness and uniqueness matter.

CAP feels abstract until you map it to what your users experience during a network split: do you prefer the system to keep responding, or to stop and avoid returning (or accepting) conflicting data?

Imagine two data centers both accept orders while they can’t talk to each other.

If you keep the checkout flow available, each side may sell the “last item” and you’ll oversell. That can be acceptable for low-stakes goods (you backorder or apologize), but painful for limited inventory drops.

If you choose consistency-first behavior, you might block new orders when you can’t confirm stock globally. Users see “try again later,” but you avoid selling something you can’t fulfill.

Money is the classic “being wrong is expensive” domain. If two replicas accept withdrawals independently during a split, an account can go negative.

Systems often prefer consistency during critical writes: decline or delay actions if they can’t confirm the latest balance. You’ll trade some availability (temporary payment failures) for correctness, auditability, and trust.

In chat and social feeds, users usually tolerate small inconsistencies: a message arrives a few seconds late, a like count is off, a view metric updates later.

Here, designing for availability can be a good product choice, as long as you’re clear which elements are “eventually correct” and you can merge updates cleanly.

The “right” CAP choice depends on the cost of being wrong: refunds, legal exposure, user trust, or operational chaos. Decide where you can accept temporary staleness—and where you must fail closed.

Once you’ve decided what you’ll do during a network split, you need mechanisms that make that decision real. These patterns show up across databases, message systems, and APIs—even if the product never mentions “CAP.”

A quorum is just “most of the replicas agree.” If you have 5 copies of some data, a majority is 3.

By requiring reads and/or writes to contact a majority, you reduce the chance of returning stale or conflicting data. For example, if a write must be acknowledged by 3 replicas, it’s harder for two isolated groups to both accept different “truths.”

The tradeoff is speed and reach: if you can’t reach a majority (because of a partition or outages), the system may refuse the operation—choosing consistency over availability.

Many “availability” issues are not hard failures but slow responses. Setting a short timeout can make the system feel snappy, but it also increases the chance you’ll treat slow successes as failures.

Retries can recover from transient blips, but aggressive retries can overload an already struggling service. Backoff (waiting a bit longer between retries) and jitter (randomness) help keep retries from turning into a traffic spike.

The key is aligning these settings with your promise: “always respond” usually means more retries and fallbacks; “never lie” usually means tighter limits and clearer errors.

If you choose to stay available during partitions, replicas may accept different updates and you must reconcile later. Common approaches include:

Retries can create duplicates: double-charging a card or submitting the same order twice. Idempotency prevents that.

A common pattern is an idempotency key (request ID) sent with each request. The server stores the first result and returns the same result for repeats—so retries improve availability without corrupting data.

Most teams “choose” a CAP stance on a whiteboard—then discover in production that the system behaves differently under stress. Validation means intentionally creating the conditions where CAP tradeoffs become visible, and checking that your system reacts the way you designed it to.

You don’t need a real cable cut to learn something. Use controlled fault injection in staging (and carefully in production) to simulate partitions:

The goal is to answer concrete questions: Do writes get rejected or accepted? Do reads serve stale data? Does the system recover automatically, and how long does reconciliation take?

If you want to validate these behaviors early (before you’ve invested weeks into wiring services together), it can help to spin up a realistic prototype quickly. For example, teams using Koder.ai often start by generating a small service (commonly a Go backend with PostgreSQL plus a React UI) and then iterating on behaviors like retries, idempotency keys, and “degraded mode” flows in a sandbox environment.

Traditional uptime checks won’t catch “available but wrong” behavior. Track:

Operators need pre-decided actions when a partition happens: when to freeze writes, when to fail over, when to degrade features, and how to validate re-merge safety.

Also plan the user-facing behavior. If you choose consistency, the message might be “We can’t confirm your update right now—please retry.” If you choose availability, be explicit: “Your update may take a few minutes to appear everywhere.” Clear wording reduces support load and preserves trust.

When you’re making a system decision, CAP is most useful as a quick “what breaks during a split?” audit—not a theoretical debate. Use this checklist before you pick a database feature, caching strategy, or replication mode.

Ask these in order:

If a network partition happens, you’re deciding which of these you’ll protect first.

Avoid a single global setting like “we are an AP system.” Instead, decide per:

Example: during a split, you might block writes to payments (prefer consistency) but keep reads for product_catalog available with cached data.

Write down what you can tolerate, with examples:

If you can’t describe inconsistency in plain examples, you’ll struggle to test it and explain incidents.

Next topics that pair well with this checklist: consensus (/blog/consensus-vs-cap), consistency models (/blog/consistency-models-explained), and SLOs/error budgets (/blog/sre-slos-error-budgets).

CAP is a mental model for replicated systems under communication failure. It’s most useful when the network is slow, lossy, or split, because that’s when replicas can’t reliably agree and you’re forced to choose between:

It helps turn “distributed is hard” into a concrete product and engineering decision.

A true CAP scenario requires both:

If your system is a single node, or if you don’t replicate state, CAP tradeoffs aren’t the central issue.

A partition is any situation where parts of your system can’t communicate reliably or within required time limits—even if every machine is still running.

Practically, “partition” often shows up as:

From the application’s perspective, “too slow” can be the same as “down.”

Consistency (C) means reads reflect the latest acknowledged write from anywhere. Users experience it as “I changed it, and everyone sees it.”

Availability (A) means every request receives a successful response (not necessarily the newest data). Users experience it as “the app keeps working,” possibly with stale results.

During a partition, you typically can’t guarantee both simultaneously for all operations.

Because partitions are not optional in distributed systems that span machines, racks, zones, or regions. If you replicate, you must define behavior when nodes can’t coordinate.

So “tolerating partitions” usually means: when communication breaks, the system still has a defined way to operate—either by rejecting/pausing some actions (favoring consistency) or by serving best-effort results (favoring availability).

If you favor consistency, you typically:

This is common for money movement, inventory reservation, and permission changes—places where being wrong is worse than being briefly unavailable.

If you favor availability, you typically:

Users see fewer hard errors, but may see stale data, duplicated effects without idempotency, or conflicting updates that need cleanup.

You can choose differently per endpoint/data type. Common mixed strategies include:

This avoids a single global “we are AP/CP” label that rarely matches real product needs.

Useful options include:

Validate by creating conditions where disagreement becomes visible:

Pick the weakest guarantee that prevents user-visible “wrongness” you can’t tolerate.

Also prepare runbooks and user messaging that match your chosen behavior (fail closed vs fail open).