Jun 01, 2025·8 min

Foxconn and the Platform Playbook of Building Technology

Foxconn shows how manufacturing orchestration, supplier networks, and logistics can turn “building tech” into a platform-style business. Learn the playbook.

Foxconn shows how manufacturing orchestration, supplier networks, and logistics can turn “building tech” into a platform-style business. Learn the playbook.

When people hear “building tech,” they picture a factory floor: machines, workers, and assembly lines. But the real differentiator is often an operating capability—a repeatable way to take a product design and turn it into millions of reliable units, on time, at a predictable cost.

That capability can behave like a platform.

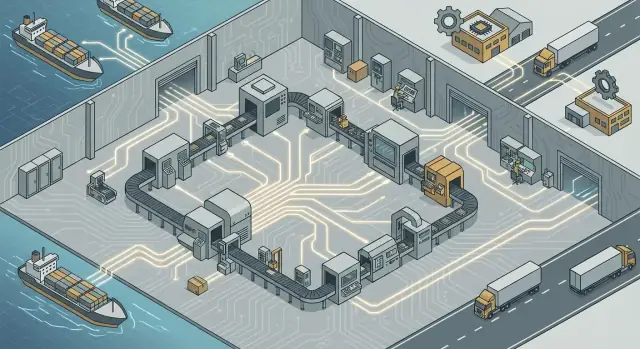

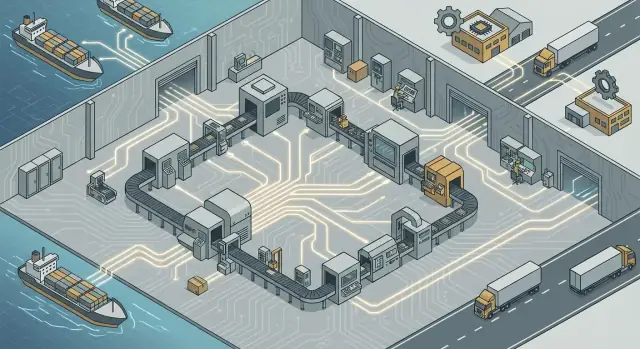

Think of manufacturing as a service layer that sits between an idea and the real world. Brands bring designs, demand forecasts, and timelines. The manufacturer provides a standardized system for sourcing parts, coordinating suppliers, assembling devices, testing quality, and shipping at scale.

The more that system can be reused across products and customers, the more it starts to look like a platform business model: a set of shared rails that many “apps” (products) can run on.

This is not a story about secret margins or insider numbers. It’s about mechanisms—how “building tech” becomes a repeatable engine:

Platforms win by lowering the cost of repeating a hard thing. In manufacturing, the “hard thing” is going from prototype to mass production without chaos. When a manufacturer accumulates playbooks, supplier relationships, quality systems, and operational data, each new product can ramp faster—with fewer surprises.

That’s the lens we’ll use to understand Foxconn: not just as a large contract manufacturer, but as an organization that productizes the act of building.

Foxconn sits in a part of the hardware world that’s easy to misunderstand: it’s not “just a factory,” and it’s not a consumer brand either. It’s a specialist in turning designs into millions of consistent units—fast—while managing the messy reality of suppliers, parts shortages, process tuning, and quality escapes.

Hardware manufacturing gets described with overlapping acronyms. Here’s the plain-English version:

At scale, the “product” is operational performance. Brands buy:

If assembly were the only thing, the lowest bidder would always win. In reality, the hard part is coordinating hundreds of parts, multiple tiers of suppliers, and tightly controlled processes—while meeting aggressive launch dates.

The “secret sauce” is repeatable execution: proven lines, trained operators, tuned test procedures, and the ability to debug manufacturing problems quickly.

Margins tend to appear in:

Margins often get competed away in mature, stable products where requirements are fixed and multiple suppliers can build to the same spec. That’s why operational know-how—and the ability to keep learning across programs—matters as much as the factory footprint itself.

When people think about contract manufacturing, they picture factories and machines. But Foxconn’s real “product” is often orchestration: the ability to reliably coordinate thousands of parts, dozens of suppliers, multiple sites, and changing requirements—so a finished device ships on time.

At a high level, the job is to keep one continuous flow moving:

Any break in the chain—one late connector, one firmware mismatch, one missing label spec—can stall the entire program. Orchestration is the work of preventing those breaks and recovering quickly when they happen.

Think of a control tower as a single operational view of reality: what’s arriving, what’s on the line, what failed test, what’s blocked, and what can be rerouted. It’s part people, part process, part systems.

The key isn’t micromanaging every station. It’s maintaining tight feedback loops so issues surface early (before thousands of units are affected) and decisions are made with full context across supply, schedule, and quality.

Orchestration depends on clean interfaces between the brand and the manufacturer:

When these inputs are ambiguous or late, even a world-class factory can produce the wrong thing efficiently.

A faster machine helps one step. Great coordination improves every step—reducing waiting, rework, and surprise shortages. That compounding effect is why “manufacturing orchestration” is a competitive advantage you can’t easily copy by buying similar equipment.

A factory’s real advantage isn’t just machines and labor—it’s access. When you’re building millions of devices, the difference between “we can get the part” and “we’re waiting on the part” becomes a business advantage.

Foxconn’s scale turns supplier management into leverage: more visibility, more options, and faster problem-solving when something breaks.

Before a supplier becomes “approved,” the bar is practical and repeatable:

Large manufacturers can run this qualification at volume—comparing suppliers side by side, building scorecards, and keeping backup options warm.

For critical parts, multi-sourcing reduces risk: if one supplier has a disruption, another can fill the gap. The tradeoff is complexity—more testing, more contracts, more coordination.

Single-sourcing can be cheaper and cleaner operationally, and sometimes it’s unavoidable (unique tooling, patented processes, or a supplier that’s simply the best). But it concentrates risk. The “right” choice often depends on how hard the part is to replace and how painful a shortage would be.

When demand spikes, suppliers prioritize customers who offer predictable forecasts, fast payment, and long-term volume. Scale also helps negotiate:

Imagine a phone build where every component is available—except one power-management chip with a 16-week lead time. You can’t “mostly” assemble a finished product; that single constrained part stalls the entire program, ties up cash in partially built inventory, and can even miss a launch window.

That’s why supplier network mastery is leverage: it’s not just buying parts cheaper—it’s keeping the whole system moving when one small piece threatens to stop it.

A product design can be “right” for the user and still be painful to build. For a manufacturer like Foxconn, the advantage isn’t just cheaper labor or bigger factories—it’s the ability to shape designs into versions that can be produced, tested, and ramped reliably.

DFM (Design for Manufacture) and DFA (Design for Assembly) mean making choices that reduce ambiguity and friction on the line: fewer unique parts, connectors that can’t be plugged in backwards, tolerances that match real tooling, and layouts that allow automated placement and easy inspection.

Small decisions add up. A screw that requires a custom bit, a cable that’s hard to route, or a component placed too close to an edge can create slowdowns, quality escapes, or extra manual steps that don’t show up in a CAD model.

When manufacturing engineers are involved early, they can flag risk before it becomes rework: parts with long lead times, materials that behave unpredictably at scale, or designs that require frequent calibration.

That reduces late-stage redesigns, missed launch dates, and expensive “temporary” fixes that become permanent. It also accelerates decision-making: teams can choose between design options based not only on performance, but on yield, throughput, and testability.

Revisions are inevitable. The operational edge is handling them without chaos: clear version control, controlled roll-in/roll-out plans, and parallel builds when needed (old rev and new rev) so production doesn’t halt while teams validate a fix.

Testing isn’t a separate phase—it’s a design requirement. Accessible test points, built-in self-checks, and fixtures designed alongside the product can shorten cycle time and improve yield.

If you can’t test it quickly and consistently, you can’t build it at scale.

When you manufacture millions of devices, “quality” isn’t a vague promise—it’s math. Small percentage changes determine whether a program makes money, ships on time, or becomes a customer-support nightmare.

At scale, the real cost isn’t only parts—it’s lost throughput. A factory that’s busy reworking yesterday’s problems can’t build today’s orders.

To keep outcomes consistent across shifts, lines, and sites, manufacturers rely on disciplined routines:

High-volume factories run a tight cycle: detect → diagnose → fix → prevent recurrence.

Detection happens through in-line testing and trend monitoring. Diagnosis uses data (traceability) plus hands-on analysis. The fix might be a process tweak, a supplier correction, or a design change. Prevention means updating standard work, training, and controls so the same failure can’t quietly creep back.

Global brands don’t just buy assembly—they buy predictability: stable yield, controlled changes, and the confidence that a problem can be isolated and corrected without stopping the whole program.

Repeatable quality becomes a competitive moat because it protects launch dates, customer experience, and reputation.

Scaling hardware isn’t just “make more.” It’s keeping the same product experience while the factory turns from a controlled workshop into a high-speed system.

The trap is assuming the hard part is unit cost; often, the real race is time-to-volume—how fast you can reach stable, high output without quality drifting.

Good capacity planning goes beyond counting assembly lines. You have to balance lines, labor, tooling, and the few critical constraints that quietly cap output.

A line can look “available” on paper, but still be blocked by:

The play is to identify the constraint early and plan around it—sometimes by duplicating the bottleneck step, sometimes by redesigning the process so it’s less fragile.

Most successful ramps follow a predictable sequence:

The key control mechanism is disciplined change management: if design tweaks, supplier substitutions, or process shortcuts happen informally during ramp, you get hidden variation that only appears at scale.

Consumer electronics demand is lumpy—product launches and holiday peaks can dwarf baseline volumes. “Flex capacity” in practice means pre-qualified options: extra shifts, mirrored lines, alternate tools, and second-source components that have already passed validation.

When you can ramp fast, you can ship earlier, capture demand, and learn sooner—often worth more than shaving cents off the bill of materials.

A factory doesn’t feel “fast” until you look at what surrounds it. For a company like Foxconn, logistics is the connective tissue that turns assembly capacity into reliable delivery dates.

Inbound logistics is about getting thousands of components (chips, displays, connectors, screws, packaging) to the right line at the right hour. The challenge isn’t distance—it’s coordination. A missing $0.20 part can stop a whole product.

Outbound logistics flips the priorities: finished goods must leave the factory in the right configuration, with the right paperwork, and on the right route to hit retail launches or online delivery windows. Here, accuracy and timing matter as much as speed.

Packaging is not decoration—it’s an operational choice. The carton size affects pallet density, air-freight cost, damage rates, and even how quickly a warehouse can process shipments.

Customs and compliance are another hidden clock. Correct product codes, certifications, and documentation prevent shipments from being held. Warehousing then becomes the buffer zone: some inventory sits near factories for flexibility, some sits closer to customers for fast fulfillment.

Last-mile coordination is often outsourced, but it still needs tight control: carrier selection, delivery appointment windows, return labels, and exception handling when something goes wrong.

Lead time is not just “how long it takes”—it’s how much certainty you can promise. Buffers (extra time, extra inventory, extra capacity) make delivery promises safer, but they tie up cash.

Too little buffer risks stockouts and missed launches; too much buffer turns into slow-moving inventory and write-downs.

When disruptions happen, teams lean on a few practical levers:

Done well, logistics becomes a product feature: predictable delivery dates, fewer surprises, and the ability to scale volume without chaos.

When people say “platform business,” they often mean software. But a high-volume manufacturer can behave like a platform too—by reusing the same production system across many different product programs.

The “platform” here is a set of repeatable processes: how a line is designed, how parts are qualified, how tests are run, how defects are handled, and how changes are approved.

Once those building blocks work, they can be copied (and improved) across programs—phones, tablets, accessories, or anything with similar components.

What gets shared is very tangible:

Over time, this becomes a library of “known-good” methods that reduce risk and speed up ramp-ups.

As a product matures, the manufacturer accumulates thousands of tiny decisions: which vendor lot codes behave best, how to tune a pick-and-place machine for a tricky package, which rework steps preserve yield, and how to interpret borderline test results.

Much of this knowledge is embedded in processes, people, and tooling—not just in documents.

So even if another factory offers a lower quoted price, a move can trigger hidden costs: re-qualifying suppliers, rebuilding fixtures, re-validating tests, retraining teams, and surviving a new yield curve.

Those switching costs are a major reason mature programs tend to stay put.

More programs running through the same manufacturing system can improve bargaining power with suppliers and create faster learning loops. A defect seen in one product can lead to a process tweak that prevents it in the next.

The result is a compounding advantage: scale improves capability, and capability attracts more scale.

Factories don’t “run on machines” as much as they run on decisions: what to build next, where to place people, which parts to quarantine, which supplier lot to re-test.

At Foxconn scale, those decisions can’t be made from memory or gut feel. They’re made from operations data—captured continuously and fed into systems that coordinate thousands of moving pieces.

A modern contract manufacturer relies on a stack of planning and execution tools: demand and capacity planning, production scheduling, warehouse systems, and shop-floor execution.

The value isn’t the software brand; it’s the closed loop between plan and reality.

On the floor, data is created everywhere: scan events when material moves, machine parameters and cycle times, test results, rework codes, operator IDs, and timestamps.

Traceability records link a finished unit back to component lots, process steps, and test stations—so when something breaks, you can narrow the blast radius fast.

“Garbage in, garbage out” is painfully literal in manufacturing. If operators skip scans, stations aren’t time-synced, or defect codes are inconsistent, then forecasts drift, yield reports lie, and teams argue about whose spreadsheet is “right.”

High-quality data requires boring discipline: standard definitions, enforced workflows, calibrated equipment, and clear ownership.

The fastest factories aren’t the ones with the most dashboards—they’re the ones where the numbers are trusted.

When the data is reliable, it improves everyday execution:

Software enables visibility and speed, but it doesn’t substitute for process discipline. Systems can tell you what happened and where; only strong operating routines—clear escalation paths, root-cause habits, and accountability—turn that data into repeatable manufacturing performance.

A helpful parallel exists in software delivery: teams also need a “control tower” across plans, changes, environments, and rollbacks. Platforms like Koder.ai apply the same platform logic—standardized rails and tight feedback loops—by letting teams build and iterate on web, backend, and mobile apps through a chat interface, with planning mode plus snapshots/rollback for controlled changes. The point isn’t that software equals manufacturing; it’s that repeatability comes from the system around the work, not just the work itself.

A manufacturing platform can look unbeatable when volumes are rising and the supply chain is stable. The weak points show up when shocks hit—because scale amplifies both wins and failures.

When production and suppliers cluster in a small set of regions, the whole system inherits local fragility. Geopolitical tensions can trigger export controls, tariffs, sanctions, or sudden compliance requirements.

Regulatory changes (labor, environment, customs) can increase lead times or costs with little warning. Even “simple” disruptions—port congestion, fuel price spikes, extreme weather—can turn a well-tuned plan into a missed launch.

Electronics often rely on parts that are single-sourced, capacity-constrained, or have long qualification cycles (custom chips, camera modules, specialty connectors, battery materials).

If one supplier slips, the factory can’t “work around it” with extra labor. The line may stop, or you ship partial volumes, or you redesign midstream—each option damages margins and timelines.

Ramping from pilot to millions of units compresses learning into weeks. If process controls, traceability, or training lag behind, small defect rates become massive recall numbers.

Worse, inconsistent quality erodes trust with the brand customer and end users at the same time.

Diversification helps when it’s real: multi-region footprints, dual builds across sites, and alternate logistics routes. Dual sourcing and pre-qualified substitutes reduce dependency on long-lead parts.

Transparency matters too—shared dashboards, early warning signals, and clear escalation paths.

Finally, contingency planning (buffer inventory in the right places, frozen change windows, and well-rehearsed response playbooks) turns “unknown unknowns” into manageable scenarios.

You don’t need Foxconn-level scale to borrow the operational advantages that make big manufacturers hard to beat. The transferable skill is orchestration: aligning design, suppliers, production, quality, and logistics so the whole system improves with every build.

A factory tour and a good quote aren’t enough. Use this checklist to pressure-test real capability:

Operational excellence starts before the first unit is built:

Keep it simple and consistent:

Treat operations as a product you improve: standard work, feedback loops, and learning that compounds.

The more you can make your process repeatable—across variants, suppliers, and sites—the more leverage you gain on cost, speed, and reliability, even without massive scale.

It means the core advantage isn’t a specific factory building, but a repeatable operating system for taking a design from prototype to millions of consistent units.

Like a software platform, the same “rails” (supplier qualification, line design, test strategy, change control, logistics playbooks) can be reused across many products and customers—reducing time, risk, and cost each time.

Brands mostly buy predictable execution, not just assembly labor:

In other words, they buy the ability to ship on time at scale without chaos.

In typical hardware programs:

Foxconn is commonly discussed as EMS/contract manufacturing, but often provides higher-value orchestration and ramp capabilities too.

Orchestration is the end-to-end coordination that keeps the whole build flowing:

A single missing part or ambiguous spec can stall everything, so orchestration is a product in itself.

A control tower is a centralized operational view that links plan to reality:

The goal is fast feedback loops—catch issues before thousands of units are affected.

Qualification usually checks four practical things:

Large manufacturers also maintain scorecards and backup options so one supplier failure doesn’t become a full program stop.

Use a risk-based approach:

If you must single-source, mitigate with actions like reserved capacity, approved alternates, safety stock for that part, and clear escalation paths.

Design choices determine how smoothly you can build and test:

A design can be great for users but still be slow, fragile, or hard to test on the line—DFM/DFA prevents that.

Track a small set of metrics that reveal drift early:

Common breakpoints are concentrated exposure and single points of failure:

Practical mitigations include dual builds across sites, pre-qualified alternates, alternate logistics routes, well-defined change freezes, and contingency buffers focused on critical parts—not everything.

Consistency matters more than having many dashboards—use definitions everyone trusts.