Jun 12, 2025·8 min

From User Stories to Database Schema: An AI-Guided Method

Learn a practical method to turn user stories, entities, and workflows into a clear database schema, and how AI reasoning can help you check gaps and rules.

Learn a practical method to turn user stories, entities, and workflows into a clear database schema, and how AI reasoning can help you check gaps and rules.

A database schema is the plan for how your app will remember things. In practical terms, it’s:

When the schema matches real work, it reflects what people actually do—create, review, approve, schedule, assign, cancel—rather than what sounds tidy on a whiteboard.

User stories and acceptance criteria describe real needs in plain language: who does what, and what “done” means. If you use those as your source, the schema is less likely to miss key details (like “we must track who approved the refund” or “a booking can be rescheduled multiple times”).

Starting from stories also keeps you honest about scope. If it isn’t in the stories (or the workflow), treat it as optional instead of quietly building a complicated model “just in case.”

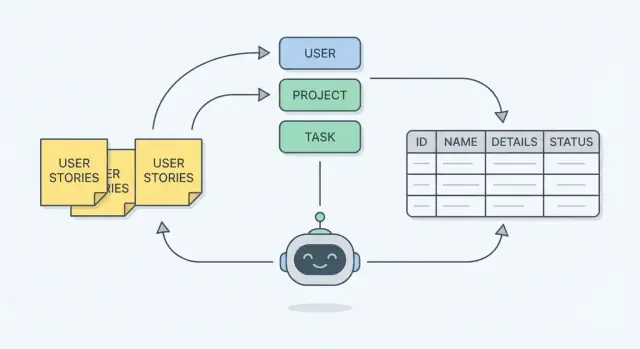

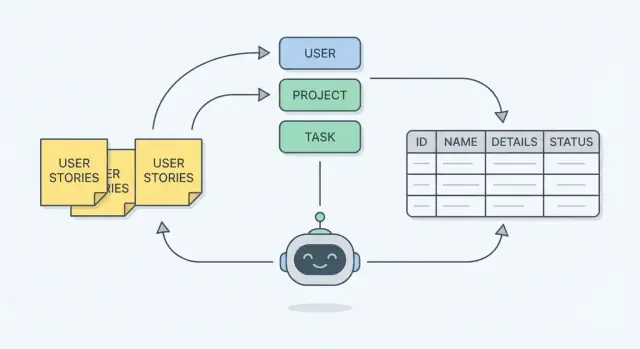

AI can help you move faster by:

AI cannot reliably:

Treat AI as a strong assistant, not the decision-maker.

If you want to turn that assistant into momentum, a vibe-coding platform like Koder.ai can help you go from schema decisions to a working React + Go + PostgreSQL app faster—while still keeping you in control of the model, constraints, and migrations.

Schema design is a loop: draft → test against stories → find missing data → refine. The goal isn’t a perfect first output; it’s a model you can trace back to each user story and confidently say: “Yes, we can store everything this workflow needs—and we can explain why each table exists.”

Before you turn requirements into tables, get clear on what you’re modeling. A good schema rarely starts from a blank page—it starts from concrete work people do and the proof you’ll need later (screens, outputs, and edge cases).

User stories are the headline, but they’re not enough by themselves. Gather:

If you’re using AI, these inputs keep the model grounded. AI can propose entities and fields quickly, but it needs real artifacts to avoid inventing structure that doesn’t match your product.

Acceptance criteria often contain the most important database rules, even when they don’t mention data explicitly. Look for statements like:

Vague stories (“As a user, I can manage projects”) hide multiple entities and workflows. Another frequent gap is missing edge cases like cancellations, retries, partial refunds, or reassignment.

Before you think about tables or diagrams, read the user stories and highlight the nouns. In requirements writing, nouns usually point to the “things” your system must remember—these often become entities in your schema.

A quick mental model: nouns become entities, while verbs become actions or workflows. If a story says “A manager assigns a technician to a job,” the likely entities are manager, technician, and job—and “assigns” hints at a relationship you’ll model later.

Not every noun deserves its own table. A noun is a strong candidate for an entity when it:

If a noun shows up only once, or only describes something else (“red button”, “Friday”), it may not be an entity.

A common mistake is turning every detail into a table. Use this rule of thumb:

Two classic examples:

AI can speed up entity discovery by scanning stories and returning a draft list of candidate nouns grouped by theme (people, work items, documents, locations). A useful prompt is: “Extract nouns that represent data we must store, and group duplicates/synonyms.”

Treat the output as a starting point, not the answer. Ask follow-ups like:

The goal of Step 1 is a short, clean list of entities you can defend by pointing back to real stories.

Once you’ve named the entities (like Order, Customer, Ticket), the next job is capturing the details you’ll need later. In a database, those details are fields (also called attributes)—the reminders your system can’t afford to forget.

Start with the user story, then read the acceptance criteria like a checklist of what must be stored.

If a requirement says “Users can filter orders by delivery date,” then delivery_date isn’t optional—it must exist as a field (or be reliably derived from other stored data). If it says “Show who approved the request and when,” you’ll likely need approved_by and approved_at.

A practical test: Will someone need this to display, search, sort, audit, or calculate something? If yes, it probably belongs as a field.

Many stories include words like “status,” “type,” or “priority.” Treat these as controlled vocabularies—a limited set of allowed values.

If the set is small and stable, a simple enum-style field can work. If it may grow, needs labels, or requires permissions (e.g., admin-managed categories), use a separate lookup table (e.g., status_codes) and store a reference.

This is how stories turn into fields you can trust—searchable, reportable, and hard to mis-enter.

Once you’ve listed the entities (User, Order, Invoice, Comment, etc.) and drafted their fields, the next step is to connect them. Relationships are the “how these things interact” layer implied by your stories.

One-to-one (1:1) means “one thing has exactly one of another thing.”

User ↔ Profile (often you can merge these unless there’s a reason to keep them separate).One-to-many (1:N) means “one thing can have many of another thing.” This is the most common.

User → Order (store user_id on Order).Many-to-many (M:N) means “many things can relate to many things.” This needs an extra table.

Databases can’t store “a list of product IDs” neatly inside Order without causing problems later (searching, updating, reporting). Instead, create a join table that represents the relationship itself.

Example:

OrderProductOrderItem (join table)OrderItem typically includes:

order_idproduct_idquantity, unit_price, discountNotice how the story’s details (“quantity”) often belong on the relationship, not on either entity.

Stories also tell you whether a connection is mandatory or sometimes missing.

Order needs a user_id (you should not allow a blank).phone can be empty.shipping_address_id might be empty for digital orders.A quick check: if the story implies you can’t create the record without the link, treat it as required. If the story says “can,” “may,” or gives exceptions, treat it as optional.

When you read a story, rewrite it as a simple pairing:

User 1:N CommentComment N:1 UserDo this for every interaction in your stories. By the end, you’ll have a connected model that matches how the work actually happens—before you ever open an ER diagram tool.

User stories tell you what people want. Workflows show you how work actually moves, step by step. Translating a workflow into data is one of the fastest ways to catch “we forgot to store that” problems—before you build anything.

Write the workflow as a sequence of actions and state changes. For example:

Those bold words often become a status field (or a small “state” table), with clear allowed values.

As you walk through each step, ask: “What would we need to know later?” Workflows commonly reveal fields like:

submitted_at, approved_at, completed_atcreated_by, assigned_to, approved_byrejection_reason, approval_notesequence for multi-step processesIf your workflow includes waiting, escalation, or handoffs, you’ll usually need at least one timestamp and one “who has it now” field.

Some workflow steps aren’t just fields—they’re separate data structures:

Give AI both: (1) the user stories and acceptance criteria, and (2) the workflow steps. Ask it to list every step and identify required data for each (state, actor, timestamps, outputs), then highlight any requirement that can’t be supported by the current fields/tables.

In platforms like Koder.ai, this “gap check” becomes especially practical because you can iterate quickly: adjust the schema assumptions, regenerate scaffolding, and keep moving without a long detour through manual boilerplate.

When you turn user stories into tables, you’re not just listing fields—you’re also deciding how the data stays identifiable and consistent over time.

A primary key uniquely identifies one record—think of it as the row’s permanent ID card.

Why every row needs one: stories imply updates, references, and history. If a story says “Support can view an order and issue a refund,” you need a stable way to point to the order—even if the customer changes their email, the address is edited, or the order status changes.

In practice, this is usually an internal id (often a number or UUID) that never changes.

A foreign key is how one table safely points to another. If orders.customer_id references customers.id, the database can enforce that every order belongs to a real customer.

This matches stories like “As a user, I can see my invoices.” The invoice isn’t floating around; it’s attached to a customer (and often to an order or subscription).

User stories regularly contain hidden uniqueness requirements:

These rules prevent confusing duplicates that otherwise show up months later as “data bugs.”

Indexes speed up searches like “find customer by email” or “list orders by customer.” Start with indexes that align with your most common queries and uniqueness rules.

What to defer: heavy indexing for rare reports or speculative filters. Capture those needs in stories, validate the schema first, then optimize based on real usage and slow-query evidence.

Normalization has one simple goal: prevent conflicting duplicates. If the same fact can be saved in two places, sooner or later it will disagree (two spellings, two prices, two “current” addresses). A normalized schema stores each fact once, then references it.

1) Watch for repeated groups

If you see patterns like “Phone1, Phone2, Phone3” or “ItemA, ItemB, ItemC,” that’s a signal for a separate table (e.g., CustomerPhones, OrderItems). Repeated groups make it hard to search, validate, and scale.

2) Don’t copy the same name/details into multiple tables

If CustomerName appears in Orders, Invoices, and Shipments, you’ve created multiple sources of truth. Keep customer details in Customers, and store only a customer_id elsewhere.

3) Avoid “multiple columns for the same thing”

Columns like billing_address, shipping_address, home_address can be fine if they’re truly different concepts. But if you’re really modeling “many addresses of different types,” use an Addresses table with a type field.

4) Separate lookups from free text

If users pick from a known set (status, category, role), model it consistently: either a constrained enum or a lookup table. This prevents “Pending” vs “pending” vs “PENDING.”

5) Check that every non-ID field depends on the right thing

A helpful gut-check: in a table, if a column describes something other than the table’s main entity, it likely belongs elsewhere. Example: Orders shouldn’t store product_price unless it means “price at time of order” (a historical snapshot).

Sometimes you do store duplicates on purpose:

The key is making it intentional: document which field is the source of truth and how copies are updated.

AI can flag suspicious duplication (repeated columns, similar field names, inconsistent “status” fields) and suggest splits into tables. Humans still choose the trade-off—simplicity vs. flexibility vs. performance—based on how the product will actually be used.

A useful rule: store facts you can’t reliably recreate later; calculate everything else.

Stored data is the source of truth: individual line items, timestamps, status changes, who did what. Calculated (derived) data is produced from those facts: totals, counters, flags like “is overdue”, and rollups like “current inventory”.

If two values can be computed from the same underlying facts, prefer storing the facts and calculating the rest. Otherwise you risk contradictions.

Derived values change whenever their inputs change. If you store both the inputs and the derived result, you now have to keep them in sync across every workflow and edge case (edits, refunds, partial shipments, backdated changes). One missed update and the database starts telling two different stories.

Example: storing order_total while also storing order_items. If someone changes a quantity or applies a discount and the total isn’t updated perfectly, finance sees one number while the cart shows another.

Workflows reveal when you need historical truth, not just “current truth.” If users need to know what the value was at the time, store a snapshot.

For an order, you may store:

order_total at checkout (snapshot), because taxes, discounts, and pricing rules may change laterFor inventory, “inventory level” is often calculated from movements (receipts, sales, adjustments). But if you need an audit trail, you store the movements and optionally store periodic snapshots for reporting speed.

For login tracking, store last_login_at as a fact (an event timestamp). “Is active in the last 30 days?” stays calculated.

Let’s use a familiar support ticket app. We’ll go from five user stories to a simple ER model (entities + fields + relationships), then check it against one workflow.

From those nouns, we get core entities:

Before (common miss): Ticket has assignee_id, but we forgot to ensure only agents can be assignees.

After: AI flags it and you add a practical rule: assignee must be a User with role = “agent” (implemented via application validation or a database constraint/policy, depending on your stack). This prevents “assigned to customer” data that breaks reports later.

A schema is only “done” when every user story can be answered with data you can actually store and query. The simplest validation step is to pick up each story and ask: “Can we answer this question from the database, reliably, for every case?” If the answer is “maybe,” your model has a gap.

Rewrite every user story as one or more test questions—things you’d expect a report, screen, or API to ask. Examples:

If you can’t express a story as a clear question, the story is unclear. If you can express it—but can’t answer it with your schema—you’re missing a field, a relationship, a status/event, or a constraint.

Create a tiny dataset (5–20 rows per key table) that includes normal cases and awkward ones (duplicates, missing values, cancellations). Then “play through” the stories using that data. You’ll quickly spot problems like “we can’t tell which address was used at the time of purchase” or “we have nowhere to store who approved the change.”

Ask AI to generate validation questions per story (including edge cases and deletion scenarios), and to list what data would be required to answer them. Compare that list to your schema: any mismatch is a concrete action item, not a vague feeling that “something’s off.”

AI can speed up data modeling, but it also increases the risk of leaking sensitive information or hard-coding bad assumptions. Treat it like a very fast assistant: useful, but it still needs guardrails.

Share inputs that are realistic enough to model, but sanitized enough to be safe:

invoice_total: 129.50, status: "paid")Avoid anything that can identify a person or reveal confidential operations:

If you need realism, generate synthetic samples that match formats and ranges—never copy production rows.

Schemas fail most often because “everyone assumed” something different. Next to your ER model (or in the same repo), keep a short decision log:

This turns AI output into team knowledge instead of a one-off artifact.

Your schema will evolve with new stories. Keep it safe by:

If you’re using a platform like Koder.ai, take advantage of guardrails like snapshots and rollback when iterating on schema changes, and export the source code when you need deeper customization or a traditional review process.

Start with the stories and highlight nouns that represent things your system must remember (e.g., Ticket, User, Category).

Promote a noun to an entity when it:

Keep a short list you can justify by pointing to specific story sentences.

Use an “attribute vs. entity” test:

customer.phone_number).A quick clue: if you ever need “many of these,” you probably need another table.

Treat acceptance criteria as a storage checklist. If a requirement says you must filter/sort/display/audit something, you must store it (or be able to derive it reliably).

Examples:

approved_by, approved_atdelivery_dateRewrite story sentences into relationship sentences:

customer_id on orders)order_items)If the relationship itself has data (quantity, price, role), that data belongs on the join table.

Model M:N with a join table that stores both foreign keys plus relationship-specific fields.

Typical pattern:

ordersproductsWalk through the workflow step-by-step and ask: “What would we need to prove this happened later?”

Common additions:

submitted_at, closed_atStart with:

id)orders.customer_id → customers.id)Then add indexes for your most common lookups (e.g., , , ). Defer speculative indexing until you see real query patterns.

Run a quick consistency check:

Phone1/Phone2, split into a child table.Denormalize later only with a clear reason (performance, reporting, audit snapshots) and document what’s authoritative.

Store facts you can’t reliably recreate later; calculate everything else.

Good to store:

Good to calculate:

If you store derived values (like ), decide how it stays in sync and test the edge cases (refunds, edits, partial shipments).

Use AI for drafts, then verify against your artifacts.

Practical prompts:

Guardrails:

emailorder_items with order_id, product_id, quantity, unit_priceAvoid storing “a list of IDs” in a single column—querying, updating, and enforcing integrity becomes painful.

created_by, assigned_to, closed_byrejection_reasonIf you need “who changed what when,” add an event/audit table rather than overwriting a single field.

emailcustomer_idstatus + created_atorder_total