Dec 10, 2025·6 min

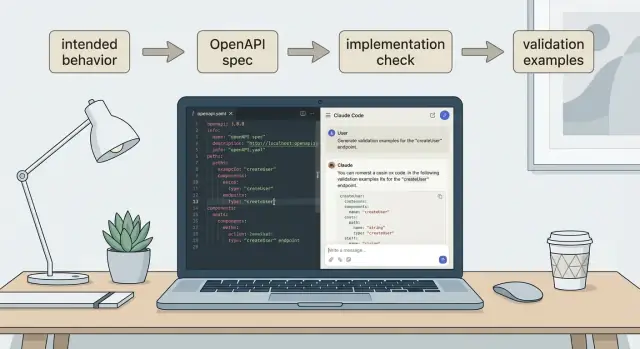

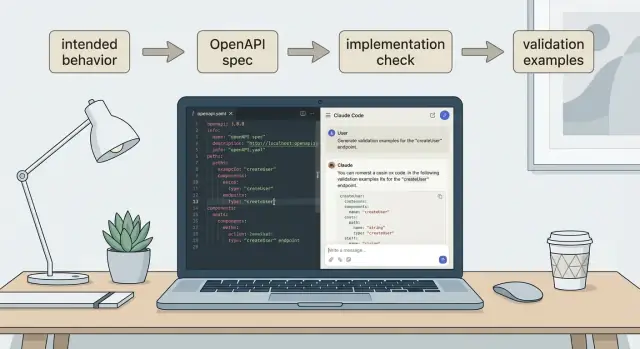

Generate OpenAPI from behavior with Claude Code, honestly

Learn how to generate OpenAPI from behavior using Claude Code, then compare it to your API implementation and create simple client and server validation examples.

Learn how to generate OpenAPI from behavior using Claude Code, then compare it to your API implementation and create simple client and server validation examples.

An OpenAPI contract is a shared description of your API: what endpoints exist, what you send, what you get back, and what errors look like. It’s the agreement between the server and anything that calls it (a web app, mobile app, or another service).

The problem is drift. The running API changes, but the spec doesn’t. Or the spec gets “cleaned up” to look nicer than reality, while the implementation keeps returning odd fields, missing status codes, or inconsistent error shapes. Over time, people stop trusting the OpenAPI file, and it becomes just another doc everyone ignores.

Drift usually comes from normal pressures: a quick fix ships without updating the spec, a new optional field is added “temporarily,” pagination evolves, or teams update different “sources of truth” (backend code, a Postman collection, and an OpenAPI file).

Keeping it honest means the spec matches real behavior. If the API sometimes returns 409 for a conflict, that belongs in the contract. If a field is nullable, say so. If auth is required, don’t leave it vague.

A good workflow leaves you with:

That last point matters because a contract only helps when it’s enforced. An honest spec plus repeatable checks turns “API documentation” into something teams can rely on.

If you start by reading code or copying routes, your OpenAPI will describe what exists today, including quirks you may not want to promise. Instead, describe what the API should do for a caller, then use the spec to verify the implementation matches.

Before writing YAML or JSON, collect a small set of facts per endpoint:

Then write behavior as examples. Examples force you to be specific and make it easier to draft a consistent contract.

For a Tasks API, a happy path example might be: “Create a task with title and get back id, title, status, and createdAt.” Add common failures: “Missing title returns 400 with {\"error\":\"title is required\"}” and “No auth returns 401.” If you already know edge cases, include them: whether duplicate titles are allowed, and what happens when a task ID doesn’t exist.

Capture rules as simple sentences that don’t depend on code details:

title is required and 1-120 characters.”limit is set (max 200).”dueDate is ISO 8601 date-time.”Finally, decide your v1 scope. If you’re unsure, keep v1 small and clear (create, read, list, update status). Save search, bulk updates, and complex filters for later so the contract stays believable.

Before you ask Claude Code to write a spec, write behavior notes in a small, repeatable format. The goal is to make it hard to accidentally “fill gaps” with guesses.

A good template is short enough that you’ll actually use it, but consistent enough that two people would describe the same endpoint similarly. Keep it focused on what the API does, not how it’s implemented.

Use one block per endpoint:

METHOD + PATH:

Purpose (1 sentence):

Auth:

Request:

- Query:

- Headers:

- Body example (JSON):

Responses:

- 200 OK example (JSON):

- 4xx example (status + JSON):

Edge cases:

Data types (human terms):

Write at least one concrete request and two responses. Include status codes and realistic JSON bodies with actual field names. If a field is optional, show one example where it’s missing.

Call out edge cases explicitly. These are the spots where specs quietly become untrue later because everyone assumed something different: empty results, invalid IDs (400 vs 404), duplicates (409 vs idempotent behavior), validation failures, and pagination limits.

Also note data types in plain words before you think about schemas: strings vs numbers, date-time formats, booleans, and enums (list allowed values). This prevents a “pretty” schema that doesn’t match real payloads.

Claude Code works best when you treat it like a careful scribe. Give it your behavior notes and strict rules for how the OpenAPI should be shaped. If you only say “write an OpenAPI spec,” you’ll usually get guesses, inconsistent naming, and missing error cases.

Paste your behavior notes first, then add a tight instruction block. A practical prompt looks like this:

You are generating an OpenAPI 3.1 YAML spec.

Source of truth: the behavior notes below. Do not invent endpoints or fields.

If anything is unclear, list it under ASSUMPTIONS and leave TODO markers in the spec.

Requirements:

- Include: info, servers (placeholder), tags, paths, components/schemas, components/securitySchemes.

- For each operation: operationId, tags, summary, description, parameters, requestBody (when needed), responses.

- Model errors consistently with a reusable Error schema and reference it in 4xx/5xx responses.

- Keep naming consistent: PascalCase schema names, lowerCamelCase fields, stable operationId pattern.

Behavior notes:

[PASTE YOUR NOTES HERE]

Output only the OpenAPI YAML, then a short ASSUMPTIONS list.

After you get the draft, scan the ASSUMPTIONS first. That’s where honesty is won or lost. Approve what’s correct, fix what’s wrong, and rerun with updated notes.

To keep naming consistent, state conventions up front and stick to them. For example: a stable operationId pattern, noun-only tag names, singular schema names, one shared Error schema, and one auth scheme name used everywhere.

If you work in a vibe-coding workspace like Koder.ai, it helps to save the YAML as a real file early and iterate in small diffs. You can see which changes came from approved behavior decisions versus details the model guessed.

Before you compare anything to production, make sure the OpenAPI file is internally consistent. This is the fastest place to catch wishful thinking and vague wording.

Read each endpoint like you’re the client developer. Focus on what a caller must send and what they can rely on receiving.

A practical review pass:

Error responses deserve extra care. Pick one shared shape and reuse it everywhere. Some teams keep it very simple ({ error: string }), others use an object ({ error: { code, message, details } }). Either can work, but don’t mix them across endpoints and examples. If you do, client code will accumulate special cases.

A quick sanity scenario helps. If POST /tasks requires title, the schema should mark it required, the failure response should show what error body you actually return, and the operation should clearly state whether auth is required.

Once the spec reads like your intended behavior, treat the running API as the truth for what clients experience today. The goal isn’t to “win” between spec and code. It’s to surface differences early and make a clear decision on each one.

For a first pass, real request/response samples are usually the simplest option. Logs and automated tests also work if they’re reliable.

Watch for common mismatches: endpoints present in one place but not the other, field name or shape differences, status code differences (200 vs 201, 400 vs 422), undocumented behaviors (pagination, sorting, filtering), and auth differences (spec says public, code requires a token).

Example: your OpenAPI says POST /tasks returns 201 with {id,title}. You call the running API and get 200 plus {id,title,createdAt}. That’s not “close enough” if you generate client SDKs from the spec.

Before you edit anything, decide how you resolve conflicts:

Keep every change small and reviewable: one endpoint, one response, one schema tweak. It’s easier to review and easier to retest.

Once you have a spec you trust, turn it into small validation examples. This is what keeps drift from creeping back in.

On the server, validation means failing fast when a request doesn’t match the contract, and returning a clear error. That protects your data and makes bugs easier to spot.

A simple way to express server validation examples is to write them as cases with three parts: input, expected output, and expected error (an error code or message pattern, not exact text).

Example (contract says title is required and must be 1 to 120 chars):

{

"name": "Create task without title returns 400",

"request": {"method": "POST", "path": "/tasks", "body": {"title": ""}},

"expect": {"status": 400, "body": {"error": {"code": "VALIDATION_ERROR"}}}

}

On the client, validation is about detecting drift before users do. If the server starts returning a different shape, or a required field disappears, your tests should flag it.

Keep client checks focused on what you truly rely on, like “a task has id, title, status.” Avoid asserting every optional field or exact ordering. You want failures on breaking changes, not harmless additions.

A few guidelines that keep tests readable:

If you build with Koder.ai, you can generate and keep these example cases next to your OpenAPI file, then update them as part of the same review when behavior changes.

Imagine a small API with three endpoints: POST /tasks creates a task, GET /tasks lists tasks, and GET /tasks/{id} returns one task.

Start by writing a few concrete examples for one endpoint, as if you were explaining it to a tester.

For POST /tasks, intended behavior could be:

{ \"title\": \"Buy milk\" } and get 201 with a new task object, including an id, the title, and done:false.{} and get 400 with an error like { \"error\": \"title is required\" }.{ \"title\": \"x\" } (too short) and get 422 with { \"error\": \"title must be at least 3 characters\" }.When Claude Code drafts the OpenAPI, the snippet for this endpoint should capture the schema, status codes, and realistic examples:

paths:

/tasks:

post:

summary: Create a task

requestBody:

required: true

content:

application/json:

schema:

$ref: '#/components/schemas/CreateTaskRequest'

examples:

ok:

value: { "title": "Buy milk" }

responses:

'201':

description: Created

content:

application/json:

schema:

$ref: '#/components/schemas/Task'

examples:

created:

value: { "id": "t_123", "title": "Buy milk", "done": false }

'400':

description: Bad Request

content:

application/json:

schema:

$ref: '#/components/schemas/Error'

examples:

missingTitle:

value: { "error": "title is required" }

'422':

description: Unprocessable Entity

content:

application/json:

schema:

$ref: '#/components/schemas/Error'

examples:

tooShort:

value: { "error": "title must be at least 3 characters" }

A common mismatch is subtle: the running API returns 200 instead of 201, or it returns { \"taskId\": 123 } instead of { \"id\": \"t_123\" }. That’s the kind of “almost the same” difference that breaks generated clients.

Fix it by choosing one truth source. If intended behavior is correct, change the implementation to return 201 and the agreed Task shape. If production behavior is already relied on, update the spec (and the behavior notes) to match reality, then add the missing validation and error responses so clients aren’t surprised.

A contract becomes dishonest when it stops describing rules and starts describing whatever your API returned on one good day. A simple test: could a new implementation pass this spec without copying today’s quirks?

One trap is overfitting. You capture one response and turn it into law. Example: your API currently returns dueDate: null for every task, so the spec says the field is always nullable. But the real rule might be “required when status is scheduled.” The contract should express the rule, not just the current dataset.

Errors are where honesty often breaks. It’s tempting to spec only success responses because they look clean. But clients need the basics: 401 when the token is missing, 403 for forbidden access, 404 for unknown IDs, and a consistent validation error (400 or 422).

Other patterns that cause trouble:

taskId in one route but id elsewhere, or priority as a string in one response and a number in another).string, everything becomes optional).A good contract is testable. If you can’t write a failing test from the spec, it’s not honest yet.

Before you hand an OpenAPI file to another team (or paste it into docs), do a fast pass for “can someone use this without reading your mind?”

Start with examples. A spec can be valid and still useless if every request and response is abstract. For each operation, include at least one realistic request example and one success response example. For errors, one example per common failure (auth, validation) is usually enough.

Then check consistency. If one endpoint returns { \"error\": \"...\" } and another returns { \"message\": \"...\" }, clients end up with branching logic everywhere. Pick a single error shape and reuse it, along with predictable status codes.

A short checklist:

A practical trick: pick one endpoint, pretend you’ve never seen the API, and answer “What do I send, what do I get back, and what breaks?” If the OpenAPI can’t answer that clearly, it’s not ready.

This workflow pays off when it runs regularly, not only during a release scramble. Pick a simple rule and stick to it: run it whenever an endpoint changes, and run it again before you publish an updated spec.

Keep ownership simple. The person who changes an endpoint updates the behavior notes and spec draft. A second person reviews the “spec vs implementation” diff like a code review. QA or support teammates often make great reviewers because they spot unclear responses and edge cases quickly.

Treat contract edits like code edits. If you’re using a chat-driven builder like Koder.ai, taking a snapshot before risky edits and using rollback when needed keeps iteration safe. Koder.ai also supports exporting source code, which makes it easier to keep the spec and implementation side by side in your repo.

A routine that usually works without slowing teams down:

Next action: pick one endpoint that already exists. Write 5-10 lines of behavior notes (inputs, outputs, error cases), generate a draft OpenAPI from those notes, validate it, then compare it to the running implementation. Fix one mismatch, retest, and repeat. After one endpoint, the habit tends to stick.

OpenAPI drift is when the API you actually run no longer matches the OpenAPI file people share. The spec might be missing new fields, status codes, or auth rules, or it might describe “ideal” behavior that the server doesn’t follow.

It matters because clients (apps, other services, generated SDKs, tests) make decisions based on the contract, not on what your server “usually” does.

Client breakages become random and hard to debug: a mobile app expects 201 but gets 200, an SDK can’t deserialize a response because a field was renamed, or error handling fails because error shapes differ.

Even when nothing crashes, teams lose trust and stop using the spec, which removes your early warning system.

Because code reflects current behavior, including accidental quirks you may not want to promise long-term.

A better default is: write intended behavior first (inputs, outputs, errors), then verify the implementation matches. That gives you a contract you can enforce, instead of a snapshot of today’s routes.

For each endpoint, capture:

Pick one error body shape and reuse it everywhere.

A simple default is either:

{ "error": "message" }, or{ "error": { "code": "...", "message": "...", "details": ... } }Then make it consistent across endpoints and examples. Consistency matters more than sophistication because clients will hard-code this shape.

Give Claude Code your behavior notes and strict rules, and tell it not to invent fields. A practical instruction set:

TODO in the spec and list it under ASSUMPTIONS.”Error) and reference them.”After generation, review the first. That’s where drift starts if you accept guesses.

Validate the spec itself first:

201)This catches “wishful” OpenAPI files before you even look at production behavior.

Treat the running API as what users experience today, and decide mismatch-by-mismatch:

Keep changes small (one endpoint or one response at a time) so you can retest quickly.

Server-side validation should reject requests that violate the contract and return a clear, consistent error (status + error code/shape).

Client-side validation should detect breaking response changes early by asserting only what you truly rely on:

Avoid asserting every optional field so tests fail on real breakages, not harmless additions.

A practical routine is:

If you’re building in Koder.ai, you can keep the OpenAPI file alongside the code, use snapshots before risky edits, and rollback if a spec/code change gets messy.

If you can write a concrete request and two responses, you’re usually far enough to draft a truthful spec.