Nov 07, 2025·8 min

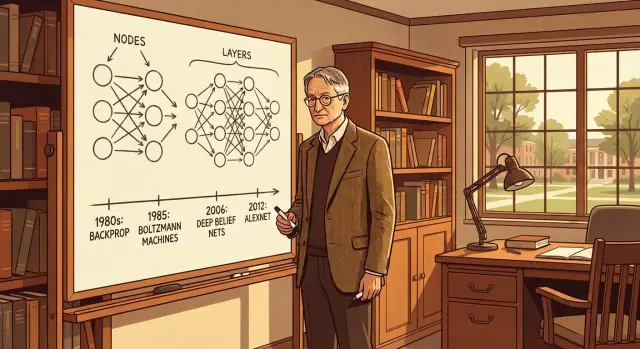

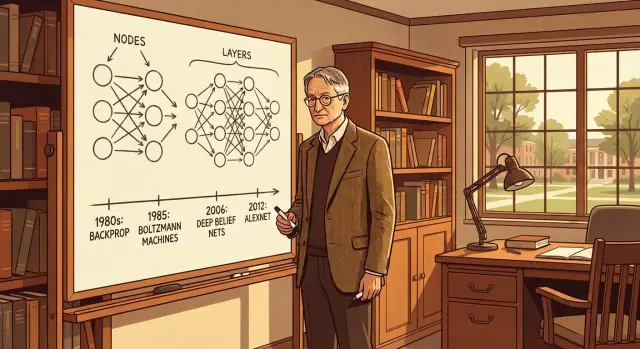

Geoffrey Hinton’s Neural Network Breakthroughs Explained

A clear guide to Geoffrey Hinton’s key ideas—from backprop and Boltzmann machines to deep nets and AlexNet—and how they shaped modern AI.

A clear guide to Geoffrey Hinton’s key ideas—from backprop and Boltzmann machines to deep nets and AlexNet—and how they shaped modern AI.

This guide is for curious, non-technical readers who keep hearing that “neural networks changed everything” and want a clean, grounded explanation of what that actually means—without needing calculus or programming.

You’ll get a plain-English tour of the ideas Geoffrey Hinton helped push forward, why they mattered at the time, and how they connect to AI tools people use now. Think of it as a story about better ways to teach computers to recognize patterns—words, images, sounds—by learning from examples.

Hinton didn’t “invent AI,” and no single person created modern machine learning. His importance is that he repeatedly helped make neural networks work in practice when many researchers believed they were dead ends. He contributed key concepts, experiments, and a research culture that treated learning representations (useful internal features) as the central problem—rather than hand-coding rules.

In the sections ahead, we’ll unpack:

In this article, a breakthrough means a shift that makes neural networks more useful: they train more reliably, learn better features, generalize to new data more accurately, or scale to bigger tasks. It’s less about a single flashy demo—and more about turning an idea into a dependable method.

Neural networks weren’t invented to “replace programmers.” Their original promise was more specific: to build machines that could learn useful internal representations from messy real-world inputs—images, speech, and text—without engineers hand-coding every rule.

A photo is just millions of pixel values. A sound recording is a stream of pressure measurements. The challenge is turning those raw numbers into concepts people care about: edges, shapes, phonemes, words, objects, intent.

Before neural networks became practical, many systems relied on handcrafted features—carefully designed measurements like “edge detectors” or “texture descriptors.” That worked in narrow settings, but it often broke when lighting changed, accents differed, or environments got more complex.

Neural networks aimed to solve this by learning features automatically, layer by layer, from data. If a system can discover the right intermediate building blocks on its own, it can generalize better and adapt to new tasks with less manual engineering.

The idea was compelling, but several barriers kept neural nets from delivering on it for a long time:

Even when neural networks were unfashionable—especially during parts of the 1990s and early 2000s—researchers like Geoffrey Hinton kept pushing on representation learning. He proposed ideas (mid-1980s onward) and revisited older ones (like energy-based models) until the hardware, data, and methods caught up.

That persistence helped keep the core goal alive: machines that learn the right representations, not just the final answer.

Backpropagation (often shortened to “backprop”) is the method that lets a neural network improve by learning from its mistakes. The network makes a prediction, we measure how wrong it was, and then we adjust the network’s internal “knobs” (its weights) to do a bit better next time.

Imagine a network trying to label a photo as “cat” or “dog.” It guesses “cat,” but the correct answer is “dog.” Backprop starts with that final error and works backward through the network’s layers, figuring out how much each weight contributed to the wrong answer.

A practical way to think about it:

Those nudges are usually done with a companion algorithm called gradient descent, which just means “take small steps downhill on the error.”

Before backprop was widely adopted, training multi-layer neural networks was unreliable and slow. Backprop made it feasible to train deeper networks because it provided a systematic, repeatable way to tune many layers at once—rather than only tweaking the final layer or guessing adjustments.

That shift mattered for the breakthroughs that followed: once you can train several layers effectively, networks can learn richer features (edges → shapes → objects, for example).

Backprop isn’t the network “thinking” or “understanding” like a person. It’s math-driven feedback: a way to adjust parameters to better match examples.

Also, backprop isn’t a single model—it’s a training method that can be used across many neural network types.

If you want a gentle deeper dive on how networks are structured, see /blog/neural-networks-explained.

Boltzmann machines were one of Geoffrey Hinton’s key steps toward making neural networks learn useful internal representations, not just spit out answers.

A Boltzmann machine is a network of simple units that can be on/off (or, in modern versions, take real values). Instead of predicting an output directly, it assigns an energy to a whole configuration of units. Lower energy means “this configuration makes sense.”

A helpful analogy is a table covered with small dips and valleys. If you drop a marble onto the surface, it will roll around and settle into a low point. Boltzmann machines try to do something similar: given partial information (like some visible units set by data), the network “wiggles” its internal units until it settles into states that have low energy—states it has learned to treat as likely.

Training classic Boltzmann machines involved repeatedly sampling many possible states to estimate what the model believes versus what the data shows. That sampling can be painfully slow, especially for large networks.

Even so, the approach was influential because it:

Most products today rely on feedforward deep networks trained with backpropagation because they’re faster and easier to scale.

The legacy of Boltzmann machines is more conceptual than practical: the idea that good models learn “preferred states” of the world—and that learning can be viewed as moving probability mass toward those low-energy valleys.

Neural networks didn’t just get better at fitting curves—they got better at inventing the right features. That’s what “representation learning” means: instead of a human hand-coding what to look for, the model learns internal descriptions (representations) that make the task easier.

A representation is the model’s own way of summarizing raw input. It’s not a label like “cat” yet; it’s the useful structure on the way to that label—patterns that capture what tends to matter. Early layers might respond to simple signals, while later layers combine them into more meaningful concepts.

Before this shift, many systems depended on expert-designed features: edge detectors for images, handcrafted audio cues for speech, or carefully engineered text statistics. Those features worked, but they often broke when conditions changed (lighting, accents, wording).

Representation learning let models adapt features to the data itself, which improved accuracy and made systems more resilient across messy real inputs.

The common thread is hierarchy: simple patterns combine into richer ones.

In image recognition, a network might first learn edge-like patterns (light-to-dark changes). Next it can combine edges into corners and curves, then into parts like wheels or eyes, and finally into whole objects like “bicycle” or “face.”

Hinton’s breakthroughs helped make this layered feature-building practical—and that’s a big reason deep learning started winning on tasks people actually care about.

Deep belief networks (DBNs) were an important stepping stone on the way to the deep neural networks people recognize today. At a high level, a DBN is a stack of layers where each layer learns to represent the layer below it—starting from raw inputs and gradually building more abstract “concepts.”

Imagine teaching a system to recognize handwriting. Instead of trying to learn everything at once, a DBN first learns simple patterns (like edges and strokes), then combinations of those patterns (loops, corners), and eventually higher-level shapes that resemble parts of digits.

The key idea is that each layer tries to model the patterns in its input without being told the correct answer yet. Then, after the stack has learned these increasingly useful representations, you can fine-tune the whole network for a specific task like classification.

Earlier deep networks often struggled to train well when initialized randomly. Training signals could get weak or unstable as they were pushed through many layers, and the network could settle into unhelpful settings.

Layer-by-layer pretraining gave the model a “warm start.” Each layer began with a reasonable understanding of the structure in the data, so the full network wasn’t searching blindly.

Pretraining didn’t magically solve every problem, but it made depth practical at a time when data, computing power, and training tricks were more limited than they are now.

DBNs helped demonstrate that learning good representations across multiple layers could work—and that depth wasn’t just theory, but a usable path forward.

Neural networks can be strangely good at “studying for the test” in the worst way: they memorize the training data instead of learning the underlying pattern. That problem is called overfitting, and it shows up any time a model looks great in practice runs but disappoints on new, real-world inputs.

Imagine you’re preparing for a driving exam by memorizing the exact route your instructor used last time—every turn, every stop sign, every pothole. If the exam uses the same route, you’ll do brilliantly. But if the route changes, your performance drops because you didn’t learn the general skill of driving; you learned one specific script.

That’s overfitting: high accuracy on familiar examples, weaker results on new ones.

Dropout was popularized by Geoffrey Hinton and collaborators as a surprisingly simple training trick. During training, the network randomly “turns off” (drops out) some of its units on each pass through the data.

This forces the model to stop relying on any single pathway or “favorite” set of features. Instead, it has to spread information across many connections and learn patterns that still hold even when parts of the network are missing.

A helpful mental model: it’s like studying while occasionally losing access to random pages of your notes—you’re pushed to understand the concept, not memorize one particular phrasing.

The main payoff is better generalization: the network becomes more reliable on data it hasn’t seen before. In practice, dropout helped make larger neural networks easier to train without them collapsing into clever memorization, and it became a standard tool in many deep learning setups.

Before AlexNet, “image recognition” wasn’t just a cool demo—it was a measurable competition. Benchmarks like ImageNet asked a simple question: given a photo, can your system name what’s in it?

The catch was scale: millions of images and thousands of categories. That size mattered because it separated ideas that sounded good in small experiments from methods that held up when the world got messy.

Progress on these leaderboards was usually incremental. Then AlexNet (built by Alex Krizhevsky, Ilya Sutskever, and Geoffrey Hinton) arrived and made the results feel less like a steady climb and more like a step change.

AlexNet showed that a deep convolutional neural network could beat the best traditional computer-vision pipelines when three ingredients were combined:

This wasn’t only “a bigger model.” It was a practical recipe for training deep networks effectively on real-world tasks.

Imagine sliding a small “window” over a photo—like moving a postage stamp across the image. Inside that window, the network looks for a simple pattern: an edge, a corner, a stripe. The same pattern-checker is reused everywhere on the image, so it can find “edge-like things” whether they’re on the left, right, top, or bottom.

Stack enough of these layers and you get a hierarchy: edges become textures, textures become parts (like wheels), and parts become objects (like bicycles).

AlexNet made deep learning feel reliable and worth investing in. If deep nets could dominate a hard, public benchmark, they could likely improve products too—search, photo tagging, camera features, accessibility tools, and more.

It helped turn neural networks from “promising research” into an obvious direction for teams building real systems.

Deep learning didn’t “arrive overnight.” It started to look dramatic when a few ingredients finally lined up—after years of earlier work showing the ideas were promising but hard to scale.

More data. The web, smartphones, and large labeled datasets (like ImageNet) meant neural networks could learn from millions of examples instead of thousands. With small datasets, big models mostly memorize.

More compute (especially GPUs). Training a deep network means doing the same math billions of times. GPUs made that affordable and fast enough to iterate. What used to take weeks could take days—or hours—so researchers could try more architectures, more hyperparameters, and fail faster.

Better training tricks. Practical improvements reduced the “it trains… or it doesn’t” randomness:

None of these changed the core idea of neural networks; they changed the reliability of getting them to work.

Once compute and data reached a threshold, improvements started stacking. Better results attracted more investment, which funded bigger datasets and faster hardware, which enabled even better results. From the outside, it looks like a jump; from the inside, it’s compounding.

Scaling up brings real costs: more energy use, more expensive training runs, and more effort to deploy models efficiently. It also increases the gap between what a small team can prototype and what only well-funded labs can train from scratch.

Hinton’s key ideas—learning useful representations from data, training deep networks reliably, and preventing overfitting—aren’t “features” you can point to in an app. They’re part of why many everyday features feel faster, more accurate, and less frustrating.

Modern search systems don’t just match keywords. They learn representations of queries and content so that “best noise-canceling headphones” can surface pages that don’t repeat the exact phrase. The same representation learning helps recommendation feeds understand that two items are “similar” even when their descriptions differ.

Machine translation improved dramatically once models got better at learning layered patterns (from characters to words to meaning). Even when the underlying model type has evolved, the training playbook—large datasets, careful optimization, and regularization ideas that grew out of deep learning—still shapes how teams build reliable language features.

Voice assistants and dictation rely on neural networks that map messy audio into clean text. Backpropagation is the workhorse that tunes these models, while techniques like dropout help them avoid memorizing quirks of a particular speaker or microphone.

Photo apps can recognize faces, group similar scenes, and let you search “beach” without manual labeling. That’s representation learning in action: the system learns visual features (edges → textures → objects) that make tagging and retrieval work at scale.

Even if you’re not training models from scratch, these principles show up in day-to-day product work: start with solid representations (often via pretrained models), stabilize training and evaluation, and use regularization when systems start “memorizing the benchmark.”

This is also why modern “vibe-coding” tools can feel so capable. Platforms like Koder.ai sit on top of current-generation LLMs and agent workflows to help teams turn plain-language specs into working web, backend, or mobile apps—often faster than traditional pipelines—while still letting you export source code and deploy like a normal engineering team.

If you want the high-level training intuition, see /blog/backpropagation-explained.

Big breakthroughs often get turned into simple stories. That makes them easier to remember—but it also creates myths that hide what actually happened, and what still matters today.

Hinton is a central figure, but modern neural networks are the result of decades of work across many groups: researchers who developed optimization methods, people who built datasets, engineers who made GPUs practical for training, and teams who proved ideas at scale.

Even within “Hinton’s work,” his students and collaborators played major roles. The real story is a chain of contributions that finally lined up.

Neural networks have been researched since the mid-20th century, with periods of excitement and disappointment. What changed wasn’t the existence of the idea, but the ability to train larger models reliably and to show clear wins on real problems.

The “deep learning era” is more of a resurgence than a sudden invention.

Deeper models can help, but they aren’t magic. Training time, cost, data quality, and diminishing returns are real constraints. Sometimes smaller models outperform bigger ones because they’re easier to tune, less sensitive to noise, or better matched to the task.

Backpropagation is a practical way to adjust model parameters using labeled feedback. Humans learn from far fewer examples, use rich prior knowledge, and don’t rely on the same kind of explicit error signals.

Neural nets can be inspired by biology without being accurate replicas of the brain.

Hinton’s story isn’t just a list of inventions. It’s a pattern: keep a simple learning idea, test it relentlessly, and upgrade the surrounding ingredients (data, compute, and training tricks) until it works at scale.

The most transferable habits are practical:

It’s tempting to take the headline lesson as “bigger models win.” That’s incomplete.

Chasing size without clear goals often leads to:

A better default is: start small, prove value, then scale—and only scale the part that’s clearly limiting performance.

If you want to turn these lessons into day-to-day practice, these are good follow-ups:

From backprop’s basic learning rule, to representations that capture meaning, to practical tricks like dropout, to a breakthrough demo like AlexNet—the arc is consistent: learn useful features from data, make training stable, and validate progress with real results.

That’s the playbook worth keeping.

Geoffrey Hinton matters because he repeatedly helped make neural networks work in practice when many researchers thought they were dead ends.

Rather than “inventing AI,” his impact comes from pushing representation learning, advancing training methods, and helping establish a research culture that focused on learning features from data instead of hand-coding rules.

A “breakthrough” here means neural networks became more dependable and useful: they trained more reliably, learned better internal features, generalized better to new data, or scaled to harder tasks.

It’s less about a flashy demo and more about turning an idea into a repeatable method teams can trust.

Neural networks aim to turn messy raw inputs (pixels, audio waveforms, text tokens) into useful representations—internal features that capture what matters.

Instead of engineers designing every feature by hand, the model learns layers of features from examples, which tends to be more robust when conditions change (lighting, accents, wording).

Backpropagation is a training method that improves a network by learning from mistakes:

It works with algorithms like gradient descent, which take small steps that reduce error over time.

Backprop made it feasible to tune many layers at once in a systematic way.

That matters because deeper networks can build feature hierarchies (e.g., edges → shapes → objects). Without a reliable way to train multiple layers, depth often failed to deliver real gains.

Boltzmann machines learn by assigning an energy (a score) to whole configurations of units; low energy means “this pattern makes sense.”

They were influential because they:

They’re less common in products today mainly because classic training is slow to scale.

Representation learning means the model learns its own internal features that make tasks easier, instead of relying on handcrafted features.

In practice, this usually improves robustness: the learned features adapt to real data variation (noise, different cameras, different speakers) better than brittle, human-designed feature pipelines.

Deep belief networks (DBNs) helped make depth practical by using layer-by-layer pretraining.

Each layer first learns structure in its input (often without labels), giving the full network a “warm start.” After that, the whole stack is fine-tuned for a specific task like classification.

Dropout fights overfitting by randomly “turning off” some units during training.

That prevents the network from relying too heavily on any single pathway and pushes it to learn features that still work when parts of the model are missing—often improving generalization on new, real-world data.

AlexNet showed a practical recipe that scaled: deep convolutional networks + GPUs + lots of labeled data (ImageNet).

It wasn’t just “a bigger model”—it demonstrated that deep learning could consistently beat traditional computer-vision pipelines on a hard, public benchmark, which triggered broad industry investment.