Aug 26, 2025·8 min

Guillermo Rauch, Vercel & Next.js: Making Deployment Simple

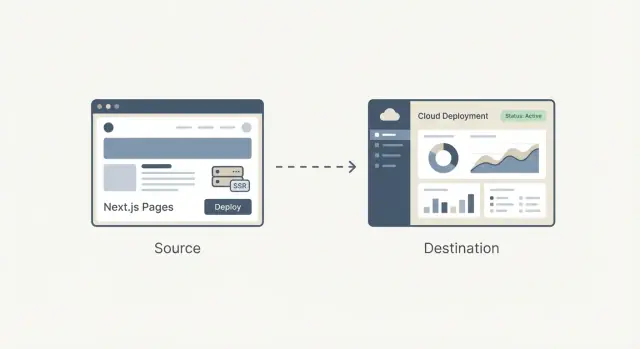

Explore how Guillermo Rauch, Vercel, and Next.js helped turn deployment, SSR, and frontend infrastructure into simpler products for mainstream builders.

Why Deployment and SSR Became Products

Not long ago, shipping a web app usually meant: build it, find a host, wire it up, and keep it running. Even if your code was simple, getting it live often forced decisions about servers, caching, build pipelines, TLS certificates, and monitoring. None of that was glamorous, but it was unavoidable—and it routinely pulled teams away from the product they were trying to ship.

From “hosting” to a repeatable workflow

The big shift is that deployment stopped being a one-off technical project and became a workflow you repeat every day. Teams wanted preview URLs for every pull request, rollbacks that don’t require detective work, and a reliable path from local code to production.

Once those needs became common across startups, agencies, and enterprises, deployment started to look less like custom engineering and more like something that could be packaged: a product with clear defaults, a UI, sensible automation, and predictable outcomes.

Why deployment and SSR felt specialized

Server-side rendering (SSR) added another layer of complexity. It’s not just “serve files”; it’s “run code on the server to generate HTML, cache it safely, and update it without breaking users.” Doing SSR well meant understanding:

- Runtime environments (Node, serverless functions)

- Caching rules and invalidation

- Performance trade-offs and cold starts

- Routing, rewrites, and headers

This was manageable for specialists, but it was easy to misconfigure—and hard to maintain as a project grew.

The core question this article answers

So what does it mean to productize frontend infrastructure?

It means turning the messy, error-prone parts of shipping a frontend—builds, deploys, previews, SSR/SSG handling, caching, and edge delivery—into a standard, mostly automatic system that works the same way across projects.

In the sections ahead, the goal is practical: understand what’s being simplified, what you gain, and what trade-offs you accept—without needing to become an ops expert.

Guillermo Rauch’s Role in the Modern Frontend Stack

Guillermo Rauch is best known today as the CEO of Vercel and a leading voice behind Next.js. His influence is less about a single invention and more about a consistent obsession: making web development feel “obvious” to the people building products.

Builder + open-source leader (the factual part)

Rauch has spent much of his career shipping developer tools in public. Before Vercel, he built and maintained popular open-source projects (notably Socket.IO) and helped grow a culture where documentation, examples, and sensible defaults are treated as part of the product—not afterthoughts.

He later founded ZEIT (renamed to Vercel), a company that focused on turning deployment into a streamlined workflow. Next.js, originally developed within that ecosystem, became the flagship framework that paired a modern frontend experience with production-friendly features.

Developer experience as a product decision

A useful way to understand Rauch’s impact is through the choices that kept repeating:

- Reduce the number of “expert-only” steps between code and a live URL.

- Make performance and rendering options accessible through conventions.

- Prefer end-to-end workflows (framework + hosting) when it removes friction.

That focus shaped both the framework and the platform: Next.js encouraged teams to adopt server-side rendering and static generation without learning an entirely new operational playbook, while Vercel pushed deployment toward a predictable, repeatable default.

Fact vs interpretation (no hero myths)

It’s easy to turn this story into a single-person narrative. A more accurate interpretation is that Rauch helped align a broader shift already underway: frontend teams wanted faster iteration, fewer handoffs, and infrastructure that didn’t require a dedicated ops specialist for every change.

Vercel and Next.js work as a case study in product thinking because they packaged those wants into defaults that mainstream teams could actually use.

Next.js in Simple Terms: What It Solves

Next.js is a React framework that gives you a “full web app starter kit” on top of React. You still build components the same way, but Next.js adds the missing pieces most teams end up assembling anyway: pages, routing, ways to fetch data, and production-friendly performance defaults.

The problems it addresses

Routing and pages: In a plain React app, you usually add a router library, decide on URL conventions, and wire everything together. Next.js makes URLs and pages a first-class feature, so your app structure maps naturally to routes.

Data loading: Real apps need data—product lists, user accounts, CMS content. Next.js provides common patterns for loading data on the server, at build time, or in the browser, without forcing every team to invent a custom setup.

Performance defaults: Next.js bakes in practical optimizations—code splitting, smarter asset handling, and rendering choices—so you get good speed without hunting for a long checklist of plugins.

How it differs from a “plain React app”

A plain React app is often “React + a pile of decisions”: routing library, build configuration, SSR/SSG tools (if needed), and conventions that only exist in your repo.

Next.js is more opinionated: it standardizes the common decisions so new developers can understand the project faster, and teams spend less time maintaining plumbing.

When Next.js may be unnecessary

Next.js can be overkill if you’re building a small, mostly static site with a handful of pages, or a simple internal tool where SEO and initial load performance aren’t priorities.

If you don’t need multiple rendering options, structured routing, or server-side data loading, a lightweight React setup (or even no React at all) may be the simpler, cheaper choice.

SSR, SSG, and Client Rendering: The Practical Differences

Modern web apps can feel mysterious because “where the page is built” changes depending on the approach. A simple way to think about SSR, SSG, and client-side rendering (CSR) is: when and where does the HTML get created?

SSR (Server-Side Rendering)

With SSR, the server generates the HTML for each request (or for many requests if caching is used). That can help with SEO and make the first view appear quickly—especially on slower devices—because the browser receives real content early.

A common misconception: SSR is not automatically faster. If every request triggers slow database calls, SSR can feel sluggish. The real speed often comes from caching (at the server, CDN, or edge) so repeated visits don’t redo the work.

SSG (Static Site Generation)

With SSG, pages are pre-built ahead of time (during a build step) and served as static files. This is great for reliability and cost, and it often delivers excellent load times because the page is already “done” before the user arrives.

SSG shines for marketing pages, docs, and content that doesn’t change every second. The trade-off is freshness: updating content may require a rebuild or an incremental update strategy.

CSR (Client-Side Rendering)

With CSR, the browser downloads JavaScript and builds the UI on the user’s device. This can be perfect for highly interactive, personalized parts of an app (dashboards, editors), but it can delay the first meaningful view and complicate SEO if the content isn’t available as HTML upfront.

Why teams mix all three

Most real products combine modes: SSG for landing pages (SEO and speed), SSR for dynamic pages that still need indexable content (product pages, listings), and CSR for logged-in experiences.

Choosing well connects directly to outcomes: SEO (discoverability), speed (conversion), and reliability (fewer incidents, steadier revenue).

Before Productization: What Deploying Web Apps Looked Like

Before platforms made deployment feel like a button-click, shipping a web app often meant assembling your own mini “infrastructure project.” Even a simple marketing site with a dynamic contact form could turn into a chain of servers, scripts, and services that had to stay perfectly in sync.

The typical workflow

A common setup looked like this: you provisioned one or more servers (or a VM), installed a web server, and wired up a CI pipeline that built your app and copied artifacts over SSH.

On top of that, you might configure a reverse proxy (like Nginx) to route requests, terminate TLS, and handle compression. Then came caching: maybe an HTTP cache, a CDN configuration, and rules about which pages were safe to cache and for how long.

If you needed SSR, you were now operating a Node process that had to be started, monitored, restarted, and scaled.

Pain points that slowed teams down

The problems weren’t theoretical—they showed up every release:

- Configuration drift: staging is “close enough” to production until it isn’t. A minor OS package difference could break builds or runtime behavior.

- Slow releases: each deploy required coordination across CI scripts, server state, environment variables, and cache invalidation.

- Hard rollbacks: reverting often meant re-deploying an old build and hoping the server state (and dependencies) still matched.

Why “it works on my machine” was so common

Local development hides the messy parts: you have a warm cache, a different Node version, a different env var, and no real traffic patterns.

Once deployed, those differences surface immediately—often as subtle SSR mismatches, missing secrets, or routing rules that behave differently behind a proxy.

The hidden tax on smaller teams

Advanced setups (SSR, multi-region performance, safe preview environments) were possible, but they demanded operational time. For many small teams, that meant settling for simpler architecture—not because it was best, but because the deployment overhead was too high.

Vercel’s Core Idea: Deployment as a Default Workflow

Vercel didn’t just automate deployment—it packaged it into a default workflow that feels like part of writing code. The product idea is simple: deployment shouldn’t be a separate “ops task” you schedule; it should be the normal outcome of everyday development.

“Git push to deploy” as a product

“Git push to deploy” is often described like a neat script. Vercel treats it more like a promise: if your code is in Git, it’s deployable—consistently, repeatedly, and without a checklist of manual steps.

That difference matters because it changes who feels confident shipping. You don’t need a specialist to interpret server settings, cache rules, or build steps each time. The platform turns those decisions into defaults and guardrails.

Preview deploys change collaboration

Preview deployments are a big part of why this feels like a workflow, not a tool. Every pull request can generate a shareable URL that matches production behavior closely.

Designers can review spacing and interactions in a real environment. QA can test the exact build that would ship. PMs can click through the feature and leave concrete feedback—without waiting for a “staging push” or asking someone to run the branch locally.

Rollbacks and environment parity as safety tools

When deploying becomes frequent, safety becomes a daily need. Quick rollbacks mean a bad release is an inconvenience, not an incident.

Environment parity—keeping previews, staging, and production behaving similarly—reduces the “it worked on my machine” problem that slows teams down.

A simple user story: marketing + app update

Imagine you’re shipping a new pricing page plus a small change in the signup flow. With preview deploys, marketing reviews the page, QA tests the flow, and the team merges with confidence.

If analytics shows a problem after launch, you roll back in minutes while you fix it—without freezing all other work.

From CDN to Edge: Frontend Infrastructure Without the Ops Team

A CDN (Content Delivery Network) is a set of servers around the world that store (and deliver) copies of your site’s files—images, CSS, JavaScript, and sometimes HTML—so users download them from a nearby location.

Caching is the rulebook for how long those copies can be reused. Good caching means faster pages and fewer hits to your origin server. Bad caching means users seeing stale content—or your team being afraid to cache anything at all.

The edge is the next step: instead of only serving files from global locations, you can run small pieces of code close to the user, at request time.

This is where “frontend infrastructure without the ops team” becomes real: many teams get global distribution and smart request handling without managing servers in multiple regions.

What edge functions are useful for

Edge functions shine when you need quick decisions before a page is served:

- Personalization: pick content based on location, device, or user segment.

- Auth checks: redirect unauthenticated users, validate a session, or set headers.

- A/B tests: route users into experiments consistently (without extra round trips).

When edge is overkill

If your site is mostly static pages, has low traffic, or you have strict requirements about exactly where code may execute (for legal or data residency reasons), edge may add complexity without clear payoff.

Trade-offs to understand

Running code across many locations can make observability and debugging harder: logs and traces are more distributed, and reproducing “it only fails in one region” issues can take time.

There’s also vendor-specific behavior (APIs, limits, runtime differences) that can affect portability.

Used thoughtfully, edge capabilities let teams get “global by default” performance and control—without hiring an ops team to stitch it together.

Framework + Platform Integration: Benefits and Trade-Offs

A framework and a hosting platform “fit together” when the platform understands what the framework produces at build time—and what it needs at request time.

That means the host can interpret build output (static files vs. server functions), apply the right routing rules (dynamic routes, rewrites), and set sensible caching behavior (what can be cached at the edge, what must be fresh).

What integration simplifies

When the platform knows the framework’s conventions, a lot of work disappears:

- Image optimization can be automatic: the framework outputs a predictable image pipeline, and the platform can run it close to users, cache results, and handle formats.

- Headers and redirects become configuration instead of custom server code. You declare intent (security headers, caching, canonical redirects) and the platform applies it consistently.

- Preview deployments and environment settings tend to “just work” because the platform can map branches, builds, and runtime settings to the framework’s expectations.

The net benefit is fewer bespoke scripts and fewer “works on my machine” deployment surprises.

The trade-offs of tight coupling

The downside is lock-in by convenience. If your app relies on platform-specific features (edge function APIs, proprietary caching rules, build plugins), moving later can mean rewriting parts of your routing, middleware, or deployment pipeline.

To keep portability in mind, separate concerns: keep business logic framework-native, document any host-specific behavior, and prefer standards where possible (HTTP headers, redirects, environment variables).

How to evaluate alternatives

Don’t assume there’s one best choice. Compare platforms by: deployment flow, supported rendering modes, cache control, edge support, observability, pricing predictability, and how easy it is to exit.

A small proof-of-concept—deploying the same repo to two providers—often reveals the real differences faster than docs.

Performance as a Feature: Speed for Users and for Teams

Performance isn’t just about bragging rights on a speed test. It’s a product feature: faster pages reduce bounce rates and improve conversions, and faster builds let teams ship more often without waiting around.

Two kinds of “fast” that matter

For users, “fast” means the page becomes usable quickly—especially on mid-range phones and slower networks. For teams, “fast” means deployments finish in minutes (or seconds) so changes can go live with confidence.

Vercel popularized the idea that you can optimize both at once by making performance part of the default workflow rather than a special project.

Incremental builds and caching (in plain terms)

A traditional build often rebuilds everything, even if you edited one line on one page. Incremental builds aim to rebuild only what changed—like updating a single chapter in a book instead of reprinting the entire book.

Caching helps by reusing previously computed results:

- Build caching reuses parts of earlier builds so the next deploy is quicker.

- Rendering caches keep precomputed pages close to users, so repeated visits don’t trigger repeated work.

In Next.js, patterns like incremental static regeneration (ISR) fit this mindset: serve a fast prebuilt page, then refresh it in the background when content changes.

Performance budgets: guardrails, not perfection

A performance budget is a simple limit you agree on—like “keep the homepage under 200KB of JavaScript” or “Largest Contentful Paint should stay under 2.5s on typical mobile.” The point isn’t to be perfect; it’s to prevent slowdowns from quietly creeping in.

Simple checks to add to your workflow

Keep it lightweight and consistent:

- Run Lighthouse in CI for key pages and fail the build if you break the budget.

- Track real-user metrics (RUM) so you’re measuring actual experience, not only lab results.

- Review bundle size changes in PRs to catch “just one more dependency” problems early.

When speed is treated as a feature, you get better user experience—and a faster team cadence—without turning every release into a performance fire drill.

Making It Mainstream: Defaults, Templates, and Learning Curves

Most tools don’t become mainstream because they’re the most flexible—they win because a new user can succeed quickly.

How mainstream builders choose

Mainstream builders (small teams, agencies, product devs without deep infra expertise) tend to evaluate platforms with simple questions:

- Can we ship a real site this week?

- Will it be fast by default?

- Can we change it safely later?

This is where templates, clear docs, and “happy path” workflows matter. A template that deploys in minutes and demonstrates routing, data fetching, and authentication is often more persuasive than a feature matrix.

Documentation that shows one recommended approach (and explains when to deviate) reduces time spent guessing.

Why sensible defaults beat endless options

A long list of toggles can feel powerful, but it forces every team to become an expert just to make basic decisions. Sensible defaults lower cognitive load:

- Good caching behavior out of the box

- A recommended rendering approach per page type

- Safe environment variable handling

- Standard build/deploy steps that rarely need customization

When defaults are right, teams spend their time on product work instead of configuration.

Common needs templates should cover

Real-world builders often start with familiar patterns:

- E-commerce: product pages, search, checkout integrations, SEO

- Content sites: CMS-driven pages, previews, image optimization

- Dashboards: auth, role-based access, fast navigation, API-heavy pages

The best templates don’t just “look nice”—they encode proven structure.

Pitfalls for newcomers

Two mistakes show up repeatedly:

- Over-engineering early: adding edge logic, complex caching, or multiple data layers before traffic justifies it.

- Confusing rendering choices: mixing SSR/SSG/client rendering without a clear reason, leading to slow pages or fragile builds.

A good learning curve nudges teams toward one clear starting point—and makes advanced choices feel like deliberate upgrades, not required homework.

Productization beyond deployment: building apps from intent

Deployment platforms productized the path from Git to production. A parallel trend is emerging upstream: productizing the path from idea to a working codebase.

Koder.ai is an example of this “vibe-coding” direction: you describe what you want in a chat interface, and the platform uses an agent-based LLM workflow to generate and iterate on a real application. It’s designed for web, server, and mobile apps (React on the frontend, Go + PostgreSQL on the backend, Flutter for mobile), with practical shipping features like source code export, deployment/hosting, custom domains, snapshots, and rollback.

In practice, this pairs naturally with the workflow this article describes: tighten the loop from intent → implementation → preview URL → production, while keeping an escape hatch (exportable code) when you outgrow the defaults.

What to Look For When Choosing a Frontend Platform

Choosing a frontend platform isn’t just picking “where to host.” It’s picking the default workflow your team will live in: how code becomes a URL, how changes get reviewed, and how outages get handled.

1) Cost model: what you actually pay for

Most platforms look similar on the homepage, then diverge in the billing details. Compare the units that map to your real usage:

- Pricing model: flat vs. usage-based, and what’s included at each tier.

- Build minutes: how CI/CD time is counted, whether previews consume the same pool, and what happens when you exceed limits.

- Bandwidth and requests: how egress is priced, whether CDN traffic is bundled, and how spikes are handled.

- Team seats: who counts as a billable user (developers, designers, contractors), and whether read-only roles exist.

A practical tip: estimate costs for a normal month and a “launch week” month. If you can’t simulate both, you’ll be surprised at the worst moment.

2) Reliability, regions, and scaling questions

You don’t need to be an infrastructure expert, but you should ask a few direct questions:

- Where can you deploy (regions/edge locations), and can you control that?

- What happens during traffic spikes—does the platform throttle, queue, or fail?

- How are incidents communicated, and is there a public status page?

- What’s the rollback story: one click, automatic, or manual?

If your customers are global, region coverage and cache behavior can matter as much as raw performance.

3) Security basics that should be non-negotiable

Look for everyday safeguards rather than vague promises:

- Secrets management: how environment variables are stored, rotated, and scoped (prod vs. preview).

- Access control: role-based permissions, SSO support, and separation between projects.

- Audit trails: visibility into deploys, config changes, and who did what.

4) A lightweight selection checklist

Use this as a quick filter before deeper evaluation:

- Can we create preview deployments for every PR with minimal setup?

- Does it support our rendering needs (static, server rendering, edge functions) without extra glue?

- Are logs, metrics, and error tracing easy to find when something breaks?

- Can we export/migrate later without rewriting the app?

Pick the platform that reduces “deployment decisions” your team has to make weekly—while still leaving you enough control when it counts.

Takeaways: A Simple Playbook for Teams Shipping the Web

Productization turns “deployment and rendering decisions” from bespoke engineering work into repeatable defaults. That reduces friction in two places that usually slow teams down: getting changes live and keeping performance predictable.

When the path from commit → preview → production is standardized, iteration speeds up because fewer releases depend on a specialist (or a lucky afternoon of debugging).

A practical migration path (start small, measure, expand)

Start with the smallest surface area that gives you feedback:

- Add preview deployments first. Treat every pull request as something you can click and review.

- Move one page or route to a framework default (for example, a marketing page to static generation, or a logged-in page to server rendering) and compare outcomes.

- Measure what matters: build time, deploy frequency, rollback time, Core Web Vitals, and “time to review” for stakeholders.

Once that works, expand gradually:

- Consolidate environments (preview/staging/prod) and define who can promote.

- Introduce edge or serverless functions only where latency or personalization benefits justify it.

- Standardize templates so new projects start with working auth, analytics, and caching patterns.

Keep learning paths lightweight

If you want to go deeper without getting lost, browse patterns and case studies on /blog, then sanity-check costs and limits on /pricing.

If you’re also experimenting with faster ways to get from requirements to a working baseline (especially for small teams), Koder.ai can be useful as a companion tool: generate a first version via chat, iterate quickly with stakeholders, and then keep the same productized path to previews, rollbacks, and production.

Convenience vs. control: how to decide

Integrated platforms optimize for speed of shipping and fewer operational decisions. The trade-off is less low-level control (custom infrastructure, unique compliance needs, bespoke networking).

Choose the “most productized” setup that still fits your constraints—and keep an exit plan (portable architecture, clear build steps) so you’re deciding from strength, not lock-in.

FAQ

What does it mean to “productize frontend infrastructure”?

It means packaging the messy parts of shipping a frontend—builds, deploys, previews, SSR/SSG handling, caching, and global delivery—into a repeatable workflow with sensible defaults.

Practically, it reduces the number of custom scripts and “tribal knowledge” required to get from a commit to a reliable production URL.

Why did deployment evolve from “hosting” into a product?

Because deployment became a daily workflow, not an occasional project. Teams needed:

- preview URLs for every pull request

- safe, fast rollbacks

- consistent environments (preview/staging/prod)

- fewer manual steps between code and production

Once these needs were common, they could be standardized into a product experience instead of reinvented per team.

Why is SSR harder to operate than static hosting?

SSR isn’t just serving files; it’s running server code to generate HTML, then making it fast and safe with caching and routing.

Common sources of complexity include runtime setup (Node/serverless), cache invalidation, cold starts, headers/rewrites, and making sure production behavior matches local development.

In practical terms, how do SSR, SSG, and CSR differ?

Think in terms of when HTML is created:

- SSR: HTML is generated at request time (often cached for speed).

- SSG: HTML is generated at build time and served as static files.

- CSR: HTML is mostly assembled in the browser after JavaScript loads.

Many apps mix them: SSG for marketing/docs, SSR for indexable dynamic pages, and CSR for highly interactive logged-in areas.

What does Next.js add compared to a plain React app?

A plain React app usually becomes “React + a pile of decisions” (routing, build config, rendering strategy, conventions). Next.js standardizes common needs:

- built-in routing conventions

- multiple data-loading patterns (server/build/client)

- production-friendly performance defaults

It’s most valuable when you need SEO, multiple rendering modes, or a consistent full-app structure.

When is Next.js overkill?

If you’re building a small mostly static site, a simple internal tool, or anything where SEO and first-load performance aren’t key constraints, Next.js can be unnecessary overhead.

In those cases, a lightweight static setup (or a simpler SPA) can be cheaper to run and easier to reason about.

How do preview deployments change team collaboration?

Preview deploys create a shareable URL for each pull request that closely matches production.

That improves collaboration because:

- QA tests the exact build that would ship

- designers review real interactions and spacing

- PMs and stakeholders can click and comment without local setup

It also reduces last-minute “staging-only” surprises.

Is SSR automatically faster for users?

Not necessarily. SSR can be slow if every request triggers expensive work (database calls, slow APIs).

SSR feels fast when paired with smart caching:

- cache rendered HTML at the server/CDN/edge when safe

- define clear freshness rules so you don’t over-fetch

- avoid doing per-request work that could be precomputed or cached

The speed win often comes from caching strategy, not SSR alone.

What are edge functions good for—and when are they not worth it?

Edge runs small pieces of code close to users, which is useful for:

- quick redirects and auth checks

- A/B test routing

- lightweight personalization

It can be overkill when your site is mostly static, traffic is low, or you have strict data residency/compliance constraints. Also expect harder debugging: logs and failures can be distributed across regions.

What are the benefits and risks of tight Next.js + platform integration?

Integration simplifies things like routing, previews, and caching because the host understands the framework’s build output. The trade-off is convenience-driven lock-in.

To keep an exit path:

- keep business logic framework-native

- prefer standards (HTTP headers, redirects, environment variables)

- document any host-specific features you rely on

A practical test is deploying the same repo to two providers and comparing the friction.