Nov 15, 2025·8 min

Hejlsberg’s TypeScript & C#: Tooling That Scales Code

How Anders Hejlsberg shaped C# and TypeScript to improve developer experience: types, IDE services, refactoring, and feedback loops that scale codebases.

How Anders Hejlsberg shaped C# and TypeScript to improve developer experience: types, IDE services, refactoring, and feedback loops that scale codebases.

A codebase rarely slows down because engineers suddenly forget how to code. It slows down because the cost of figuring things out rises: understanding unfamiliar modules, making a change safely, and proving the change didn’t break something else.

As a project grows, “just search and edit” stops working. You start paying for every missing hint: unclear APIs, inconsistent patterns, weak autocomplete, slow builds, and unhelpful errors. The result isn’t only slower delivery—it’s more cautious delivery. Teams avoid refactors, postpone cleanup, and ship smaller, safer changes that don’t move the product forward.

Anders Hejlsberg is a key figure behind both C# and TypeScript—two languages that treat developer experience (DX) as a first-class feature. That matters because a language isn’t only syntax and runtime behavior; it’s also the tooling ecosystem around it: editors, refactoring tools, navigation, and the quality of feedback you get while writing code.

This article looks at TypeScript and C# through a practical lens: how their design choices help teams move faster as systems and teams expand.

When we say a codebase is “scaling,” we’re usually talking about several pressures at once:

Strong tooling reduces the tax created by those pressures. It helps engineers answer common questions instantly: “Where is this used?”, “What does this function expect?”, “What changes if I rename this?”, and “Is this safe to ship?” That’s developer experience—and it’s often the difference between a large codebase that evolves and one that ossifies.

Anders Hejlsberg’s influence is easiest to see not as a set of quotes or personal milestones, but as a consistent product philosophy that shows up in mainstream developer tooling: make common work fast, make mistakes obvious early, and make large-scale change safer.

This section isn’t a biography. It’s a practical lens for understanding how language design and the surrounding tooling ecosystem can shape day-to-day engineering culture. When teams talk about “good DX,” they often mean things that were deliberately designed into systems like C# and TypeScript: predictable autocomplete, sensible defaults, refactoring you can trust, and errors that point you toward a fix instead of just rejecting your code.

You can observe the impact in the expectations developers now bring to languages and editors:

These outcomes are measurable in practice: fewer avoidable runtime mistakes, more confident refactors, and shorter time spent “re-learning” a codebase when joining a team.

C# and TypeScript run in different environments and serve different audiences: C# is often used for server-side and enterprise applications, while TypeScript targets the JavaScript ecosystem. But they share a similar DX goal: help developers move quickly while reducing the cost of change.

Comparing them is useful because it separates principles from platform. When similar ideas succeed in two very different runtimes—static language on a managed runtime (C#) and a typed layer over JavaScript (TypeScript)—it suggests the win is not accidental. It’s the result of explicit design choices that prioritize feedback, clarity, and maintainability at scale.

Static typing often gets framed as taste: “I like types” vs. “I prefer flexibility.” In large codebases, it’s less about preference and more about economics. Types are a way to keep everyday work predictable as more people touch more files more often.

A strong type system gives names and shapes to your program’s promises: what a function expects, what it returns, and what states are allowed. That turns implicit knowledge (held in someone’s head or buried in docs) into something the compiler and tooling can enforce.

Practically, that means fewer “Wait, can this be null?” conversations, clearer autocompletion, safer navigation across unfamiliar modules, and faster code review because intent is encoded in the API.

Compile-time checks fail early, often before code is merged. If you pass the wrong argument type, forget a required field, or misuse a return value, the compiler flags it immediately.

Runtime failures show up later—maybe in QA, maybe in production—when a particular code path executes with real data. Those bugs are usually costlier: they’re harder to reproduce, they interrupt users, and they create reactive work.

Static types don’t prevent every runtime bug, but they remove a big class of “this should never have compiled” errors.

As teams grow, the common breakpoints are:

Types act like a shared map. When you change a contract, you get a concrete list of what needs updating.

Typing has costs: a learning curve, extra annotations (especially at boundaries), and occasional friction when the type system can’t express what you mean cleanly. The key is using types strategically—most heavily at public APIs and shared data structures—so you get the scaling benefits without turning development into paperwork.

A feedback loop is the tiny cycle you repeat all day: edit → check → fix. You change a line, your tools immediately verify it, and you correct what’s wrong before your brain context-switches.

In a slow loop, “check” mostly means running the app and relying on manual testing (or waiting for CI). That delay turns small mistakes into scavenger hunts:

The longer the gap between edit and discovery, the more expensive each fix becomes.

Modern languages and their tooling shorten the loop to seconds. In TypeScript and C#, your editor can flag problems as you type, often with a suggested fix.

Concrete examples that get caught early:

user.address.zip, but address isn’t guaranteed to exist.return makes the rest of the function impossible to execute.These aren’t “gotchas”—they’re common slips that fast tools turn into quick corrections.

Fast feedback reduces coordination costs. When the compiler and language service catch mismatches immediately, fewer issues escape into code review, QA, or other teams’ workstreams. That means less back-and-forth (“What did you mean here?”), fewer broken builds, and fewer “someone changed a type and my feature exploded” surprises.

At scale, speed isn’t just runtime performance—it’s how quickly developers can be confident their change is valid.

“Language services” is a plain name for the set of editor features that make code feel searchable and safe to touch. Think: autocomplete that understands your project, “go to definition” that jumps to the right file, rename that updates every usage, and diagnostics that underline problems before you run anything.

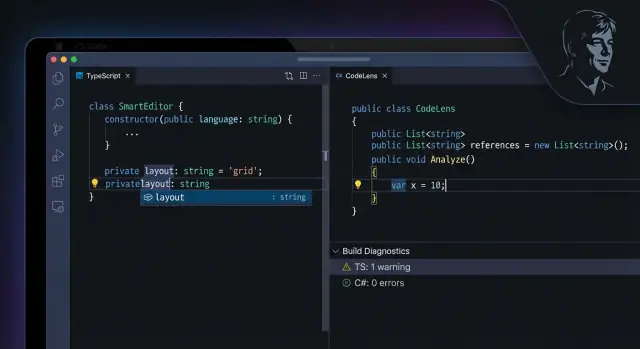

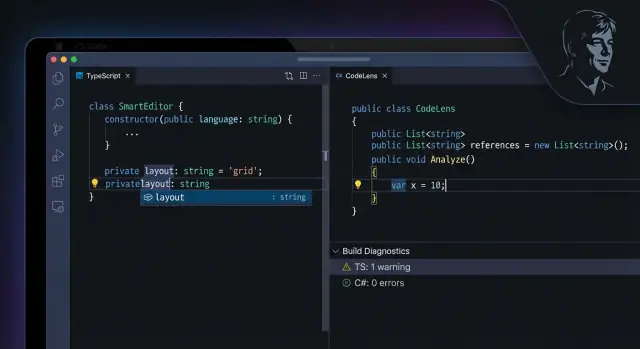

TypeScript’s editor experience works because the TypeScript compiler isn’t only for producing JavaScript—it also powers the TypeScript Language Service, the engine behind most IDE features.

When you open a TS project in VS Code (or other editors that speak the same protocol), the language service reads your tsconfig, follows imports, builds a model of your program, and continuously answers questions like:

That’s why TypeScript can offer accurate autocomplete, safe renames, jump-to-definition, “find all references,” quick fixes, and inline errors while you’re still typing. In large JavaScript-heavy repositories, that tight loop is a scaling advantage: engineers can edit unfamiliar modules and get immediate guidance about what will break.

C# benefits from a similar principle, but with especially deep IDE integration in common workflows (notably Visual Studio and also VS Code via language servers). The compiler platform supports rich semantic analysis, and the IDE layers on refactorings, code actions, project-wide navigation, and build-time feedback.

This matters when teams grow: you spend less time “mentally compiling” the codebase. Instead, the tools can confirm intent—showing you the real symbol you’re calling, the nullability expectations, the impacted call sites, and whether a change ripples across projects.

At small size, tooling is a nice-to-have. At large size, it’s how teams move without fear. Strong language services make unfamiliar code easier to explore, easier to change safely, and easier to review—because the same facts (types, references, errors) are visible to everyone, not just the person who originally wrote the module.

Refactoring isn’t a “spring cleaning” event you do after the real work. In large codebases, it is the real work: continuously reshaping code so new features don’t get slower and riskier each month.

When a language and its tooling make refactoring safe, teams can keep modules small, names accurate, and boundaries clear—without scheduling a risky, multi-week rewrite.

Modern IDE support in TypeScript and C# tends to cluster around a few high-leverage moves:

These are small actions, but at scale they’re the difference between “we can change this” and “nobody touch that file.”

Text search can’t tell whether two identical words refer to the same symbol. Real refactoring tools use the compiler’s understanding of the program—types, scopes, overloads, module resolution—to update meaning, not just characters.

That semantic model is what makes it possible to rename an interface without touching a string literal, or to move a method and automatically fix every import and reference.

Without semantic refactoring, teams routinely ship avoidable breakage:

This is where developer experience directly becomes engineering throughput: safer change means more change, earlier—and less fear baked into the codebase.

TypeScript succeeds largely because it doesn’t ask teams to “start over.” It accepts that most real projects begin as JavaScript—messy, fast-moving, and already shipping—and then lets you layer safety on top without blocking momentum.

TypeScript uses structural typing, which means compatibility is based on a value’s shape (its fields and methods), not the name of a declared type. If an object has { id: number }, it can usually be used anywhere that shape is expected—even if it came from a different module or wasn’t explicitly “declared” as that type.

It also leans heavily on type inference. You often get meaningful types without writing them:

const user = { id: 1, name: "Ava" }; // inferred as { id: number; name: string }

Finally, TypeScript is gradual: you can mix typed and untyped code. You can annotate the most critical boundaries first (API responses, shared utilities, core domain modules), and leave the rest for later.

This incremental path is why TypeScript fits existing JavaScript codebases. Teams can convert file-by-file, accept some any early on, and still gain immediate wins: better autocomplete, safer refactors, and clearer function contracts.

Most organizations start with moderate settings, then ratchet stricter rules as the codebase stabilizes—enabling options like strict, tightening noImplicitAny, or improving strictNullChecks coverage. The key is progress without paralysis.

Types model what you expect to happen; they don’t prove runtime behavior. You still need tests—especially for business rules, integration edges, and anything involving I/O or untrusted data.

C# has grown around a simple idea: make the “normal” way of writing code also the safest and most readable way. That matters when a codebase stops being something one person can hold in their head and becomes a shared system maintained by many.

Modern C# leans into syntax that reads like business intent rather than mechanics. Small features add up: clearer object initialization, pattern matching for “handle these shapes of data,” and expressive switch expressions that reduce nested if blocks.

When dozens of developers touch the same files, these affordances reduce the need for tribal knowledge. Code reviews become less about deciphering and more about validating behavior.

One of the most practical scaling improvements is nullability. Instead of treating null as an ever-present surprise, C# helps teams express intent:

That shifts many defects from production to compile time, and it’s especially helpful in large teams where APIs are used by people who didn’t write them.

As systems grow, so do network calls, file I/O, and background work. C#’s async/await makes asynchronous code read like synchronous code, which reduces the cognitive load of handling concurrency.

Instead of threading callbacks through the codebase, teams can write straightforward flows—fetch data, validate, then continue—while the runtime manages the waiting. The result is fewer timing-related bugs and fewer custom conventions that new team members must learn.

C#’s productivity story is inseparable from its language services and IDE integration. In large solutions, strong tooling changes what’s feasible day to day:

This is how teams keep momentum. When the IDE can reliably answer “where is this used?” and “what will this change break?”, developers make improvements proactively instead of avoiding change.

The lasting pattern is consistency: common tasks (null handling, async workflows, refactors) are supported by both the language and the tools. That combination turns good engineering habits into the easiest path—exactly what you want when scaling a codebase and the team behind it.

When a codebase is small, a vague error can be “good enough.” At scale, diagnostics become part of your team’s communication system. TypeScript and C# both reflect a Hejlsberg-style bias toward messages that don’t just stop you—they show you how to move forward.

Helpful diagnostics tend to share three traits:

This matters because errors are often read under pressure. A message that teaches reduces back-and-forth and turns “blocked” time into “learning” time.

Errors enforce correctness right now. Warnings are where long-term health is protected: deprecated APIs, unreachable code, questionable null usage, implicit any, and other “it works today, but might break later” issues.

Teams can treat warnings as a gradual ratchet: start permissive, then tighten policies over time (and ideally keep warning counts from creeping up).

Consistent diagnostics create consistent code. Instead of relying on tribal knowledge (“we don’t do that here”), the tools explain the rule at the moment it matters.

That’s a scaling advantage: newcomers can fix issues they’ve never seen before because the compiler and IDE effectively document intent—right in the error list.

When a codebase grows, slow feedback becomes a daily tax. It rarely shows up as a single “big” problem; it’s death by a thousand waits: longer builds, slower test suites, and CI pipelines that turn quick checks into an hour-long context switch.

A few common symptoms appear across teams and stacks:

Modern language toolchains increasingly treat “rebuild everything” as the last resort. The key idea is simple: most edits only affect a small slice of the program, so tools should reuse prior work.

Incremental compilation and caching typically rely on:

This isn’t just about faster builds. It’s what enables “live” language services to stay responsive while you type, even in large repositories.

Treat IDE responsiveness like a product metric, not a nice-to-have. If rename, find references, and diagnostics take seconds, people stop trusting them—and stop refactoring.

Set explicit budgets (for example: local build under X minutes, key editor actions under Y ms, CI checks under Z minutes). Measure them continuously.

Then act on the numbers: split hot paths in CI, run the smallest test set that proves a change, and invest in caching and incremental workflows wherever you can. The goal is simple: make the fastest path the default path.

Large codebases don’t usually fail because of one bad function—they fail because boundaries blur over time. The easiest way to keep change safe is to treat APIs (even internal ones) as products: small, stable, and intentional.

In both TypeScript and C#, types turn “how to call this” into an explicit contract. When a shared library exposes well-chosen types—narrow inputs, clear return shapes, meaningful enums—you reduce the number of “implicit rules” that only live in someone’s head.

For internal APIs, this matters even more: teams move, ownership changes, and the library becomes a dependency you can’t “just read quickly.” Strong types make misuse harder and refactors safer because callers break at compile time instead of in production.

A maintainable system is usually layered:

This is less about “architecture purity” and more about making it obvious where changes should happen.

APIs evolve. Plan for it:

Support these habits with automation: lint rules that ban internal imports, code review checklists for API changes, and CI checks that enforce semver and prevent accidental public exports. When the rules are executable, maintainability stops being a personal virtue and becomes a team guarantee.

Large codebases don’t fail because a team “picked the wrong language.” They fail because change gets risky and slow. The practical pattern behind both TypeScript and C# is simple: types + tooling + fast feedback make everyday change safer.

Static types are most valuable when they’re paired with great language services (autocomplete, navigation, quick fixes) and tight feedback loops (instant errors, incremental builds). That combination turns refactoring from a stressful event into a routine activity.

Not every scaling win comes from the language alone—workflow matters too. Platforms like Koder.ai aim to compress the “edit → check → fix” loop even further by letting teams build web, backend, and mobile apps through a chat-driven workflow (React on the web, Go + PostgreSQL on the backend, Flutter for mobile), while still keeping the outcome grounded in real, exportable source code.

In practice, features like planning mode (to clarify intent before changes), snapshots and rollback (to make refactors safer), and built-in deployment/hosting with custom domains map directly onto the same theme in this article: reduce the cost of change and keep feedback tight as systems grow.

Start with tooling wins. Standardize an IDE setup, enable consistent formatting, add linting, and make “go to definition” and rename work reliably across the repo.

Add safety gradually. Turn on type checking where it hurts most (shared modules, APIs, high-churn code). Move toward stricter settings over time instead of trying to “flip the switch” in a week.

Refactor with guardrails. Once types and tooling are trustworthy, invest in bigger refactors: extracting modules, clarifying boundaries, and deleting dead code. Use the compiler and IDE to do the heavy lifting.

Pick one upcoming feature and treat it as a pilot: tighten types in the touched area, require green builds in CI, and measure lead time and bug rate before/after.

If you want more ideas, browse related engineering posts at /blog.

Developer experience (DX) is the day-to-day cost of making a change: understanding code, editing safely, and proving it works. As codebases and teams grow, that “figuring things out” cost dominates—and good DX (fast navigation, reliable refactors, clear errors) keeps delivery speed from collapsing under complexity.

In a large repo, time is lost to uncertainty: unclear contracts, inconsistent patterns, and slow feedback.

Good tooling reduces that uncertainty by answering quickly:

Because it’s a repeatable design philosophy that shows up in both ecosystems: prioritize fast feedback, strong language services, and safe refactoring. The practical lesson isn’t “follow a person,” it’s “build a workflow where common work is fast and mistakes are surfaced early.”

Static types turn implicit assumptions into checkable contracts. That helps most when many people touch the same code:

Compile-time checks fail early—often while you type or before merging—so you fix issues when context is fresh. Runtime failures show up later (QA/production), with higher costs: reproduction, interruption, and emergency patching.

A practical rule: use types to prevent “should never have compiled” errors, and use tests to validate real runtime behavior and business rules.

TypeScript is designed for incremental adoption in existing JavaScript:

A common migration strategy is file-by-file conversion and tightening strictness over time.

C# tends to make the “normal” way of coding align with readability and safety at scale:

null.async/await keeps asynchronous flows readable.The result is less reliance on personal conventions and more consistency enforced by tools.

Language services are the editor features powered by a semantic understanding of your code (not just text). They typically include:

In TypeScript, this is largely driven by the TypeScript compiler + language service; in C#, by compiler/analysis infrastructure plus IDE integration.

Use semantic refactoring (IDE/compiler-backed), not search-and-replace. Good refactors rely on understanding scopes, overloads, module resolution, and symbol identity.

Practical habits:

Treat speed as a product metric and optimize the feedback loop:

The goal is to keep edit → check → fix tight enough that people stay confident making changes.

tsconfig