Nov 12, 2025·8 min

From Nonprofit Lab to AI Leader: The History of OpenAI

Explore the history of OpenAI, from its nonprofit origins and key research milestones to the launch of ChatGPT, GPT-4, and its evolving mission.

Explore the history of OpenAI, from its nonprofit origins and key research milestones to the launch of ChatGPT, GPT-4, and its evolving mission.

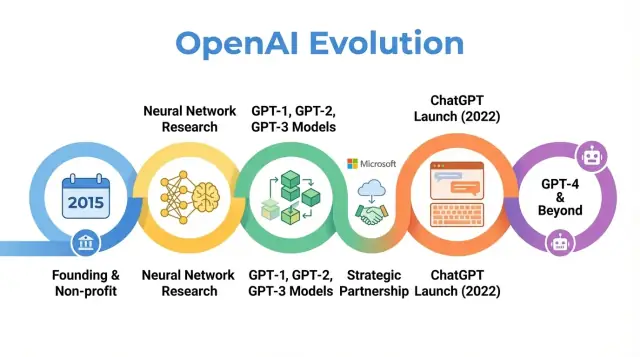

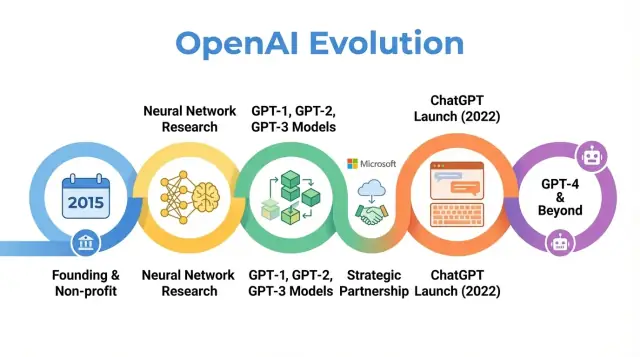

OpenAI is an AI research and deployment company whose work has shaped how people think about artificial intelligence, from early research papers to products like ChatGPT. Understanding how OpenAI evolved—from a small nonprofit lab in 2015 to a central player in AI—helps explain why modern AI looks the way it does today.

OpenAI’s story is not just a sequence of model releases. It is a case study in how mission, incentives, technical breakthroughs, and public pressure interact. The organization began with a strong emphasis on open research and broad benefit, then restructured to attract capital, formed a deep partnership with Microsoft, and launched products used by hundreds of millions of people.

Tracing OpenAI’s history illuminates several wider trends in AI:

Mission and values: OpenAI was founded with the stated goal of ensuring that artificial general intelligence benefits all of humanity. How that mission has been interpreted and revised over time reveals the tensions between idealistic goals and commercial realities.

Research breakthroughs: The progression from early projects to systems like GPT-3, GPT-4, DALL·E, and Codex tracks a broader shift toward large-scale foundation models that power many current AI applications.

Governance and structure: The move from a pure nonprofit to a capped-profit entity, and the creation of complex governance mechanisms, highlight how new organizational forms are being tried to manage powerful technologies.

Public impact and scrutiny: With ChatGPT and other releases, OpenAI moved from a research lab known mainly within AI circles to a household name, drawing attention to safety, alignment, and regulation debates that now shape policy discussions worldwide.

This article follows OpenAI’s journey from 2015 to its latest developments, showing how each phase reflects broader shifts in AI research, economics, and governance—and what that might mean for the future of the field.

OpenAI was founded in December 2015, at a point when machine learning—especially deep learning—was rapidly improving but still far from general intelligence. Image recognition benchmarks were falling, speech systems were getting better, and companies like Google, Facebook, and Baidu were pouring money into AI.

A growing concern among researchers and tech leaders was that advanced AI might end up controlled by a handful of powerful corporations or governments. OpenAI was conceived as a counterweight: a research organization focused on long‑term safety and broad distribution of AI’s benefits, rather than on narrow commercial advantage.

From day one, OpenAI defined its mission in terms of artificial general intelligence (AGI), not just incremental machine learning progress. The core statement was that OpenAI would work to ensure AGI, if created, “benefits all of humanity.”

That mission had several concrete implications:

Early public blog posts and the founding charter emphasized both openness and caution: OpenAI would publish much of its work, but would also consider the societal impact of releasing powerful capabilities.

OpenAI began as a nonprofit research lab. The initial funding commitments were announced at around $1 billion in pledged support, though this was a long‑term pledge rather than upfront cash. Key early backers included Elon Musk, Sam Altman, Reid Hoffman, Peter Thiel, Jessica Livingston, and YC Research, along with support from companies such as Amazon Web Services and Infosys.

The early leadership team combined startup, research, and operating experience:

This mix of Silicon Valley entrepreneurship and top‑tier AI research shaped OpenAI’s early culture: highly ambitious about pushing the frontier of AI capabilities, but organized as a mission‑driven nonprofit aimed at long‑term global impact rather than short‑term commercialization.

When OpenAI launched as a nonprofit research lab in 2015, its public promise was simple but ambitious: advance artificial intelligence while sharing as much as possible with the wider community.

The early years were defined by an "open by default" philosophy. Research papers were posted quickly, code was usually released, and internal tools were turned into public projects. The idea was that accelerating broad scientific progress—and scrutiny—would be safer and more beneficial than concentrating capabilities inside a single company.

At the same time, safety was already part of the conversation. The team discussed when openness might increase misuse risk and began sketching ideas for staged release and policy reviews, even if those ideas were still informal compared with later governance processes.

OpenAI’s early scientific focus spanned several core areas:

These projects were less about polished products and more about testing what was possible with deep learning, compute, and clever training regimes.

Two of the most influential outputs of this era were OpenAI Gym and Universe.

Both projects reflected a commitment to shared infrastructure rather than proprietary advantage.

During this nonprofit period, OpenAI was often portrayed as a mission-driven counterweight to large tech firms’ AI labs. Peers valued the quality of its research, the availability of code and environments, and the willingness to engage in safety discussions.

Media coverage emphasized the unusual combination of high-profile funders, a non-commercial structure, and a promise to publish openly. That reputation—as an influential, open research lab concerned with long-term consequences—set expectations that would later shape reactions to every strategic shift the organization made.

The turning point in OpenAI’s history was its decision to focus on large transformer-based language models. This shift transformed OpenAI from a primarily research-focused nonprofit into a company known for foundational models that others build on.

GPT-1 was modest by later standards—117 million parameters, trained on BookCorpus—but it offered a crucial proof of concept.

Instead of training separate models for each NLP task, GPT-1 showed that a single transformer model, trained with a simple objective (predict the next word), could be adapted with minimal fine-tuning to tasks like question answering, sentiment analysis, and textual entailment.

For OpenAI’s internal roadmap, GPT-1 validated three ideas:

GPT-2 pushed the same basic recipe much further: 1.5 billion parameters and a much larger web-derived dataset. Its outputs were often startlingly coherent: multi-paragraph articles, fictional stories, and summaries that looked, at a glance, like human writing.

Those capabilities raised alarms about potential misuse: automated propaganda, spam, harassment, and fake news at scale. Instead of releasing the full model immediately, OpenAI adopted a staged release strategy:

This was one of the first high-profile examples of OpenAI explicitly tying deployment decisions to safety and social impact, and it shaped how the organization thought about disclosure, openness, and responsibility.

GPT-3 scaled up again—this time to 175 billion parameters. Instead of relying mainly on fine-tuning for each task, GPT-3 demonstrated “few-shot” and even “zero-shot” learning: the model could often perform a new task simply from instructions and a few examples in the prompt.

That level of generality changed how both OpenAI and the broader industry thought about AI systems. Rather than building many narrow models, one large model could serve as a general-purpose engine for:

Crucially, OpenAI chose not to open-source GPT-3. Access was offered via a commercial API. This decision marked a strategic pivot:

GPT-1, GPT-2, and GPT-3 trace a clear arc in OpenAI’s history: scaling transformers, discovering emergent capabilities, wrestling with safety and misuse, and laying the commercial groundwork that would later support products like ChatGPT and the continued development of GPT-4 and beyond.

By 2018, OpenAI’s leaders were convinced that staying a small, donation-funded lab would not be enough to build and safely steer very large AI systems. Training frontier models already required tens of millions of dollars in compute and talent, with cost curves clearly pointing much higher. To compete for top researchers, scale experiments, and secure long-term access to cloud infrastructure, OpenAI needed a structure that could attract serious capital without abandoning its original mission.

In 2019, OpenAI launched OpenAI LP, a new “capped-profit” limited partnership. The goal was to unlock large external investment while keeping the nonprofit’s mission — ensuring that artificial general intelligence benefits all of humanity — at the top of the decision-making hierarchy.

Traditional venture-backed startups are ultimately accountable to shareholders seeking uncapped returns. OpenAI’s founders worried that this would create strong pressure to prioritize profit over safety, openness, or careful deployment. The LP structure was a compromise: it could issue equity-like interests and raise money at scale, but under a different set of rules.

In the capped-profit model, investors and employees can earn returns on their stakes in OpenAI LP, but only up to a fixed multiple of their original investment (for early investors, often cited as up to 100x, with lower caps in later tranches). Once that cap is reached, any additional value created is meant to flow to the nonprofit parent to be used in line with its mission.

This contrasts sharply with typical startups, where equity value can, at least theoretically, grow without limit and where maximizing shareholder value is the legal and cultural default.

OpenAI Nonprofit remains the controlling entity. Its board oversees OpenAI LP and is chartered to prioritize humanity’s interests over those of any particular group of investors or employees.

Formally:

This governance design is meant to give OpenAI the fundraising and hiring flexibility of a commercial organization while retaining mission-first control.

The restructuring sparked debate inside and outside the organization. Supporters argued it was the only practical way to secure the billions likely required for cutting-edge AI research while still constraining profit incentives. Critics questioned whether any structure that offers large returns could truly resist commercial pressure, and whether the caps were high enough or clearly enforced.

Practically, OpenAI LP opened the door to large strategic investments, most notably from Microsoft, and allowed the company to offer competitive compensation packages pegged to potential upside. That, in turn, enabled OpenAI to scale its research teams, expand training runs for models like GPT-3 and GPT-4, and build the infrastructure needed to deploy systems such as ChatGPT at global scale — all while maintaining a formal governance link back to its nonprofit origins.

In 2019, OpenAI and Microsoft announced a multi‑year partnership that reshaped both companies’ roles in AI. Microsoft invested a reported $1 billion, combining cash and Azure cloud credits, in exchange for becoming OpenAI’s preferred commercial partner.

The deal aligned with OpenAI’s need for massive compute resources to train increasingly large models, while giving Microsoft access to cutting‑edge AI that could differentiate its products and cloud platform. Over subsequent years, the relationship deepened through additional financing and technical collaboration.

OpenAI chose Microsoft Azure as its primary cloud platform for several reasons:

This made Azure the default environment for training and serving models like GPT‑3, Codex, and later GPT‑4.

The partnership led to one of the world’s largest AI supercomputing systems, built on Azure for OpenAI’s workloads. Microsoft highlighted these clusters as flagship examples of Azure’s AI capabilities, while OpenAI relied on them to push model size, training data, and experimentation speed.

This joint infrastructure effort blurred the line between “customer” and “partner”: OpenAI effectively influenced Azure’s AI roadmap, and Azure was tuned to OpenAI’s needs.

Microsoft received exclusive licensing rights to some OpenAI technologies, most notably GPT‑3. That allowed Microsoft to embed OpenAI models across its products—Bing, Office, GitHub Copilot, Azure OpenAI Service—while other companies accessed them via OpenAI’s own API.

This exclusivity fueled debate: supporters argued it provided the funding and distribution needed to scale powerful AI safely; critics worried it concentrated influence over frontier models in a single major tech company.

At the same time, the partnership gave OpenAI mainstream visibility. Microsoft’s branding, product integrations, and enterprise sales channels helped move OpenAI systems from research demos into everyday tools used by millions, shaping public perception of OpenAI as both an independent lab and a core Microsoft AI partner.

As OpenAI’s models improved at understanding and generating language, the team pushed into new modalities: images and code. This shift expanded OpenAI’s work from writing and dialogue into visual creativity and software development.

CLIP (Contrastive Language–Image Pretraining), announced in early 2021, was a major step toward models that understand the world more like humans do.

Instead of training only on labeled images, CLIP learned from hundreds of millions of image–caption pairs scraped from the public web. It was trained to match images with their most likely text descriptions and to distinguish them from incorrect ones.

This gave CLIP surprisingly general abilities:

CLIP became a foundation for later generative image work at OpenAI.

DALL·E (2021) applied GPT-style architectures to images, generating pictures directly from text prompts: “an armchair in the shape of an avocado” or “a storefront sign that says ‘openai’”. It demonstrated that language models could be extended to produce coherent, often whimsical imagery.

DALL·E 2 (2022) significantly improved resolution, realism, and controllability. It introduced features such as:

These systems changed how designers, marketers, artists, and hobbyists prototype ideas, shifting some creative work from manual drafting toward iterative prompt‑driven exploration.

Codex (2021) took the GPT-3 family and adapted it to source code, training on large public codebases. It can translate natural language into working snippets for languages like Python, JavaScript, and many others.

GitHub Copilot, built on Codex, brought this into everyday development tools. Programmers began receiving entire functions, tests, and boilerplate as suggestions, using natural-language comments as guidance.

For software development, Codex hinted at a gradual shift:

Together, CLIP, DALL·E, and Codex showed that OpenAI’s approach could extend beyond text into vision and code, broadening the impact of its research across art, design, and engineering.

OpenAI launched ChatGPT as a free "research preview" on November 30, 2022, announcing it in a short blog post and tweet rather than a major product campaign. The model was based on GPT‑3.5 and optimized for dialogue, with guardrails to refuse some harmful or unsafe requests.

Usage surged almost immediately. Millions of people signed up within days, and ChatGPT became one of the fastest‑growing consumer applications ever. Screenshots of conversations flooded social media as users tested its ability to write essays, debug code, draft emails, and explain complex topics in plain language.

ChatGPT’s appeal came from its versatility rather than a single narrow use case.

In education, students used it to summarize readings, generate practice questions, translate or simplify academic articles, and get step‑by‑step explanations of math or science problems. Teachers experimented with it to design syllabi, draft rubrics, and create differentiated learning materials, even as schools debated whether and how it should be allowed.

At work, professionals asked ChatGPT to draft emails, marketing copy, and reports, outline presentations, generate code snippets, write test cases, and serve as a brainstorming partner for product ideas or strategies. Individual freelancers and small businesses especially leaned on it as a low‑cost assistant for content and analysis.

For everyday problem‑solving, people turned to ChatGPT for travel plans, cooking ideas from what was in their fridge, basic legal and medical explanations (typically with disclaimers to seek professional advice), and help learning new skills or languages.

The initial research preview was free to reduce friction and collect feedback on failures, misuse, and missing capabilities. As usage grew, OpenAI faced both high infrastructure costs and user demand for more reliable access.

In February 2023, OpenAI introduced ChatGPT Plus, a subscription plan that offered faster responses, priority access during peak times, and early access to new features and models such as GPT‑4. This created a recurring revenue stream while keeping a free tier for broad access.

Over time, OpenAI added more business‑oriented options: API access to the same conversational models, tools for integration into products and workflows, and offerings such as ChatGPT Enterprise and team plans aimed at organizations needing higher security, admin controls, and compliance features.

ChatGPT’s sudden visibility intensified long‑running debates about AI.

Regulators and policymakers worried about privacy, data protection, and compliance with existing laws, especially in regions like the European Union. Some authorities temporarily restricted or investigated ChatGPT while assessing whether data collection and processing met legal standards.

Educators confronted plagiarism and academic integrity concerns as students could generate essays and homework answers that were difficult to detect. This led to bans or strict policies in some schools, while others shifted toward assignments that emphasized process, oral exams, or in‑class work.

Ethicists and researchers raised alarms about misinformation, overreliance on AI for critical decisions, bias in responses, and potential impacts on creative and knowledge‑work jobs. There were also questions about training data, copyright, and the rights of artists and writers whose work might have influenced model behavior.

For OpenAI, ChatGPT marked a turning point: it transformed the organization from a mostly research‑focused lab into a company at the center of global discussions about how powerful language models should be deployed, governed, and integrated into everyday life.

OpenAI released GPT-4 in March 2023 as a major step beyond GPT-3.5, the model that initially powered ChatGPT. GPT-4 improved on reasoning, following complex instructions, and maintaining coherence over longer conversations. It also became far better at handling nuanced prompts, such as explaining legal clauses, summarizing technical papers, or drafting code from ambiguous requirements.

Compared to GPT-3.5, GPT-4 reduced many obvious failure modes: it was less likely to invent sources when asked for citations, handled edge cases in math and logic problems more reliably, and produced more consistent outputs across repeated queries.

GPT-4 introduced multimodal capabilities: in addition to text, it can accept images as input in some configurations. This enables use cases like describing charts, reading handwritten notes, interpreting UI screenshots, or analyzing photos to extract structured information.

On standardized benchmarks, GPT-4 significantly outperformed previous models. It achieved near top-percentile scores on simulated professional exams such as the bar exam, SAT, and various advanced placement tests. It also improved on coding and reasoning benchmarks, reflecting stronger abilities in both language understanding and problem solving.

GPT-4 quickly became the core of OpenAI’s API and powered a new wave of third‑party products: AI copilots in productivity suites, coding assistants, customer support tools, education platforms, and vertical-specific applications in fields like law, finance, and healthcare.

Despite these advances, GPT-4 still hallucinates, can be prompted into unsafe or biased outputs, and lacks genuine understanding or up‑to‑date factual knowledge. OpenAI focused heavily on alignment research for GPT-4—using techniques like reinforcement learning from human feedback, red‑teaming, and system‑level safety rules—but emphasizes that careful deployment, monitoring, and ongoing research are still required to manage risks and misuse.

From its early years, OpenAI framed safety and alignment as core to its mission, not an afterthought to product launches. The organization has consistently stated that its goal is to build highly capable AI systems that are aligned with human values and deployed in a way that benefits everyone, not just its shareholders or early partners.

In 2018, OpenAI published the OpenAI Charter, which formalized its priorities:

The Charter effectively acts as a governance compass, shaping decisions about research directions, deployment speed, and external partnerships.

As models grew more capable, OpenAI built dedicated safety and governance functions alongside its core research teams:

These groups influence launch decisions, access tiers, and usage policies for models like GPT‑4 and DALL·E.

A defining technical approach has been reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF). Human labelers review model outputs, rank them, and train a reward model. The main model is then optimized to produce responses closer to human‑preferred behavior, reducing toxic, biased, or unsafe outputs.

Over time, OpenAI has layered RLHF with additional techniques: system-level safety policies, content filters, fine‑tuning for specific domains, and monitoring tools that can restrict or flag high‑risk use.

OpenAI has participated in public safety frameworks, such as voluntary commitments with governments, model reporting practices, and frontier model safety standards. It has collaborated with academics, civil-society organizations, and security researchers on evaluations, red‑teaming, and audits.

These collaborations, combined with formal documents like the Charter and evolving usage policies, form the backbone of OpenAI’s approach to governing increasingly powerful AI systems.

OpenAI’s rapid rise has been shadowed by criticism and internal strain, much of it centered on how closely the organization still aligns with its original mission of broad, safe benefit.

Early on, OpenAI emphasized open publication and sharing. Over time, as models like GPT-2, GPT-3, and GPT-4 grew more capable, the company shifted toward limited releases, API-only access, and fewer technical details.

Critics argued this move conflicted with the promise implied by the name “OpenAI” and the early nonprofit messaging. Supporters within the company have argued that withholding full model weights and training details is necessary to manage misuse risks and security concerns.

OpenAI has responded by publishing safety evaluations, system cards, and policy documents, while still keeping core model weights proprietary. It presents this as a balance between openness, safety, and competitive pressure.

As OpenAI deepened its partnership with Microsoft—integrating models into Azure and products like Copilot—observers raised concerns about concentration of compute, data, and decision-making power.

Critics worry that a small number of companies now control the most advanced general-purpose models and the vast infrastructure behind them. Others argue that aggressive commercialization (ChatGPT Plus, enterprise offerings, and exclusive licensing) diverges from the original nonprofit mission of broadly shared benefit.

OpenAI’s leadership has framed revenue as necessary to fund expensive research while maintaining a capped-profit structure and a charter that prioritizes humanity’s interests over shareholder returns. It has also introduced programs like free access tiers, research partnerships, and some open-source tools to demonstrate public benefit.

Internal disagreements over how fast to move, how open to be, and how to prioritize safety have surfaced repeatedly.

Dario Amodei and others left in 2020 to found Anthropic, citing different views on safety and governance. Later, resignations from key safety researchers, including Jan Leike in 2024, publicly highlighted concerns that short-term product goals were taking precedence over long-term safety work.

The most visible rupture occurred in November 2023, when the board briefly removed CEO Sam Altman, citing a loss of trust. After intense employee backlash and negotiations involving Microsoft and other stakeholders, Altman returned, the board was reconstituted, and OpenAI pledged governance reforms, including a new Safety and Security Committee.

These episodes underscored that the organization is still wrestling with how to reconcile rapid deployment, commercial success, and its stated responsibilities around safety and broad benefit.

OpenAI has shifted from a small, research-focused nonprofit into a central infrastructure provider for AI, influencing how new tools are built, regulated, and understood.

Instead of just publishing models, OpenAI now operates a full platform used by startups, enterprises, and solo developers. Through APIs for models like GPT-4, DALL·E, and future systems, it has become:

This platform role means OpenAI is not only advancing research—it is setting defaults for how millions of people first experience powerful AI.

OpenAI’s work pushes competitors and open-source communities to respond with new models, training methods, and safety approaches. That competition accelerates progress while sharpening debates about openness, centralization, and commercialization of AI.

Governments and regulators increasingly look to OpenAI’s practices, transparency reports, and alignment research when writing rules for AI deployment, safety evaluations, and responsible use. Public conversations about ChatGPT, GPT-4, and future systems heavily influence how society imagines both the risks and benefits of AI.

As models grow more capable, unresolved issues around OpenAI’s role become more important:

These questions will shape whether future AI systems amplify existing inequalities or help reduce them.

Developers and businesses can:

Individuals can:

OpenAI’s future influence will depend not only on its internal decisions, but on how governments, competitors, civil society, and everyday users choose to engage, critique, and demand accountability from the systems it builds.

OpenAI was founded in 2015 as a nonprofit research lab with the mission to ensure that artificial general intelligence (AGI), if created, benefits all of humanity.

Several factors shaped its creation:

This origin story continues to influence OpenAI’s structure, partnerships, and public commitments today.

AGI (artificial general intelligence) refers to AI systems that can perform a wide range of cognitive tasks at or above human level, rather than being narrow tools optimized for a single job.

OpenAI’s mission is to:

This mission is formalized in the OpenAI Charter and shapes major decisions about research directions and deployment.

OpenAI moved from a pure nonprofit to a “capped‑profit” limited partnership (OpenAI LP) to raise the large amounts of capital needed for cutting‑edge AI research while trying to keep its mission at the top of the hierarchy.

Key points:

It is an experiment in governance, and its effectiveness remains a subject of debate.

Microsoft provides OpenAI with massive cloud compute via Azure and has invested billions of dollars in the company.

The partnership includes:

In return, OpenAI gains the resources needed to train and deploy frontier models at global scale, while Microsoft gets differentiated AI capabilities for its ecosystem.

The GPT series shows a progression in scale, capabilities, and deployment strategy:

OpenAI began with an “open by default” approach—releasing papers, code, and tools like OpenAI Gym widely. As models became more powerful, it shifted toward:

OpenAI argues this is necessary to reduce misuse risks and manage security. Critics counter that it undermines the original promise implied by the name “OpenAI” and concentrates power in one company.

OpenAI uses a mix of organizational structures and technical methods to manage safety and misuse:

These measures reduce risk but do not eliminate problems such as hallucinations, bias, and potential misuse, which remain active research and governance challenges.

ChatGPT, launched in late 2022, made large language models directly accessible to the general public through a simple chat interface.

It changed AI adoption by:

This public visibility also intensified scrutiny of OpenAI’s governance, business model, and safety practices.

OpenAI’s models, especially Codex and GPT‑4, are already altering parts of knowledge and creative work:

Potential benefits:

Risks and concerns:

You can engage with OpenAI’s ecosystem in several ways:

Each step pushed technical boundaries while forcing new decisions about safety, access, and commercialization.

The net impact will depend heavily on policy, organizational choices, and how individuals and firms choose to integrate AI into their workflows.

In all cases, it helps to stay informed about how models are trained and governed, and to push for transparency, accountability, and equitable access as these systems grow more capable.