Aug 02, 2025·8 min

Hitachi: Industrial Tech Meets Enterprise Software at Scale

Explore how Hitachi blends industrial systems with enterprise software to turn operational data into safer, more efficient outcomes across the physical economy.

Explore how Hitachi blends industrial systems with enterprise software to turn operational data into safer, more efficient outcomes across the physical economy.

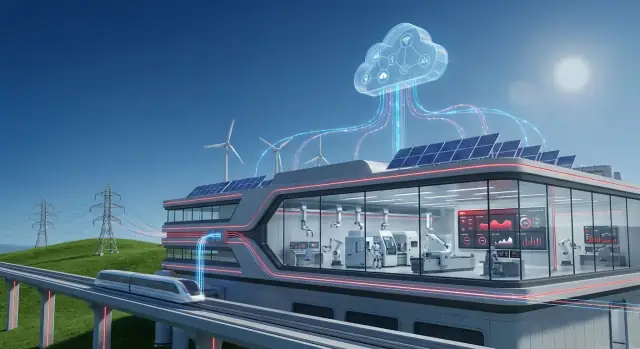

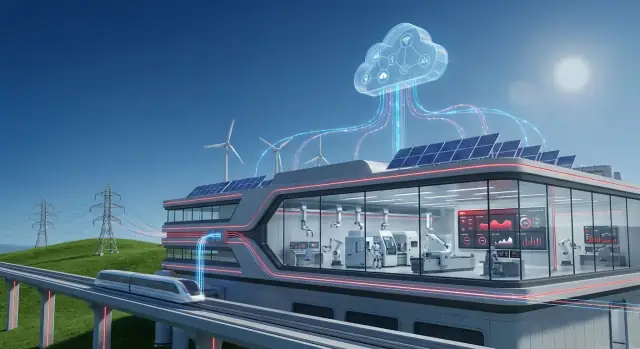

The “physical economy” is the part of business that moves atoms, not just information. It’s the power plant balancing supply and demand, the rail network keeping trains on schedule, the factory turning raw materials into finished goods, and the water utility maintaining pressure and quality across a city.

In these environments, software isn’t only measuring clicks or conversions—it’s influencing real equipment, real people, and real costs. A late maintenance decision can become a breakdown. A minor process drift can turn into scrap, downtime, or a safety incident.

That’s why data matters differently here: it has to be timely, trustworthy, and tied to what’s happening on the ground.

When your “product” is availability, throughput, and reliability, data becomes a practical tool:

But there are real trade-offs. You can’t pause a factory to “update later.” Sensors can be noisy. Connectivity isn’t guaranteed. And decisions often need to be explainable to operators, engineers, and regulators.

This is where OT and IT convergence starts to matter.

When OT and IT work together, operational signals can trigger business workflows—like creating a work order, checking inventory, scheduling crews, and tracking outcomes.

You’ll learn where value typically shows up (uptime, maintenance, energy efficiency), what it takes architecturally (edge-to-cloud patterns), and what to watch out for (security, governance, and change management). The goal is a clear, realistic picture of how industrial data becomes better decisions—not just more dashboards.

Hitachi sits at an intersection that’s increasingly important for modern organizations: the systems that run physical operations (trains, power networks, factories, water plants) and the software that plans, measures, and improves how those operations perform.

That background matters because industrial environments tend to reward proven engineering, long asset lifecycles, and steady incremental improvements—not quick platform swaps.

When people say “industrial technology” in this context, they’re usually talking about the stack that keeps real-world processes stable and safe:

This side of the house is about physics, constraints, and operating conditions—heat, vibration, load, wear, and the realities of field work.

“Enterprise software” is the set of systems that turns operations into coordinated decisions and auditable actions across teams:

Hitachi’s story is relevant because it reflects a broader shift: industrial companies want operational data to flow into business workflows without losing context or control. The goal isn’t “more data” for its own sake—it’s tighter alignment between what’s happening on the ground and how the organization plans, maintains, and improves its assets over time.

Industrial sites are full of signals that describe what’s happening right now: temperatures drifting, vibration rising, power quality fluctuating, throughput slowing, alarms chattering. Factories, rail systems, mines, and utilities generate these signals continuously because physical equipment must be monitored to stay safe, efficient, and compliant.

The challenge isn’t getting more data—it’s turning raw readings into decisions people trust.

Most operations pull from a mix of real-time control systems and business records:

On their own, each source tells a partial story. Together, they can explain why performance changes and what to do next.

Operational data is messy for predictable reasons. Sensors get replaced, tags get renamed, and networks drop packets. Common issues include:

If you’ve ever wondered why dashboards disagree, it’s often because timestamps, naming, or units don’t line up.

A reading becomes meaningful only when you can answer: what asset is this, where is it, and what state was it in?

“Vibration = 8 mm/s” is far more actionable when it’s tied to Pump P-204, in Line 3, running at 80% load, after a bearing change last month, during a specific product run.

This context—asset hierarchy, location, operating mode, and maintenance history—is what allows analytics to separate normal variation from early warning signs.

The operational data journey is essentially a move from signals → clean time series → contextualized events → decisions, so teams can shift from reacting to alarms to managing performance deliberately.

Operational technology (OT) is the stuff that runs a physical operation: machines, sensors, control systems, and the procedures that keep a plant, rail network, or power substation working safely.

Information technology (IT) is the stuff that runs the business: ERP, finance, HR, procurement, customer systems, and the networks and apps employees use every day.

OT–IT convergence is simply getting these two worlds to share the right data at the right time—without putting production, safety, or compliance at risk.

Most problems aren’t technical first; they’re operational.

To make convergence practical, you typically need a few building blocks:

A practical approach is to pick one high-value use case (for example, predictive maintenance on a critical asset), connect a limited data set, and agree on clear success metrics.

Once the workflow is stable—data quality, alerts, approvals, and security—expand to more assets, then more sites. This keeps OT comfortable with reliability and change control while giving IT the standards and visibility it needs to scale.

Industrial systems generate valuable signals—temperatures, vibration, energy use, throughput—but they don’t all belong in the same place. “Edge-to-cloud” simply means splitting the work between computers near the equipment (edge) and centralized platforms (cloud or data center), based on what the operation needs.

Certain decisions must happen in milliseconds or seconds. If a motor is overheating or a safety interlock triggers, you can’t wait for a round trip to a distant server.

Edge processing helps with:

Centralized platforms are best when the value depends on combining data across lines, plants, or regions.

Typical “cloud-side” work includes:

Architecture is also about trust. Good governance defines:

When edge and cloud are designed together, you get speed on the shop floor and consistency at the enterprise level—without forcing every decision to live in one place.

Industrial software creates the most visible business value when it connects how assets behave with how the organization responds. It’s not just about knowing a pump is degrading—it’s about making sure the right work gets planned, approved, executed, and learned from.

Asset Performance Management (APM) focuses on reliability outcomes: monitoring condition, detecting anomalies, understanding risk, and recommending actions that reduce failures. It answers, “What is likely to fail, when, and what should we do about it?”

Enterprise Asset Management (EAM) is the system of record for asset and maintenance operations: asset hierarchies, work orders, labor, permits, inventory, and compliance history. It answers, “How do we plan, track, and control the work and costs?”

Used together, APM can prioritize the right interventions, while EAM ensures those interventions happen with proper controls—supporting reliability and tighter cost control.

Predictive maintenance becomes meaningful when it drives measurable outcomes such as:

Programs that work typically start with fundamentals:

Analytics without follow-through becomes a dashboard nobody trusts. If a model flags bearing wear but no one creates a work order, reserves parts, or captures findings after repair, the system can’t learn—and the business won’t feel the benefit.

A digital twin is best understood as a practical, working model of a real asset or process—built to answer “what if?” questions before you change the real thing. It’s not a 3D animation for presentations (though it can include visuals). It’s a decision tool that combines how something is designed to behave with how it is actually behaving.

Once a twin reflects reality closely enough, teams can test options safely:

This is where simulation becomes valuable: you can compare scenarios and choose the one that best fits production goals, cost, risk, and compliance.

Useful twins blend two data types:

Industrial software programs (including edge-to-cloud setups) help keep these sources synchronized so the twin reflects day-to-day operations rather than “as designed” assumptions.

Digital twins aren’t “set and forget.” Common issues include:

A good approach is to start with a narrowly defined decision (one line, one asset class, one KPI), prove value, then expand.

Connecting factories, rail systems, energy assets, and buildings creates value—but it also changes the risk profile. When software touches physical operations, security is no longer only about protecting data; it’s about keeping systems stable, keeping people safe, and keeping service running.

In office IT, a breach is often measured in lost information or downtime for knowledge workers. In operational technology (OT), interruptions can stop production lines, damage equipment, or create unsafe conditions.

OT environments also tend to run older systems for long lifecycles, can’t always reboot on demand, and must prioritize predictable behavior over rapid change.

Start with fundamentals that fit industrial realities:

Industrial programs should align security actions with operational safety and compliance needs: clear change control, traceability of who did what, and evidence that critical systems remain within safe operating limits.

Assume something will fail—whether it’s a cyber event, misconfiguration, or hardware fault. Maintain offline backups, rehearse restore procedures, define recovery priorities, and assign clear responsibilities across IT, OT, and operations leadership.

Reliability improves when everyone knows what to do before an incident happens.

Sustainability in heavy industry isn’t mainly a branding exercise—it’s an operations problem. When you can see what machines, plants, fleets, and supply networks are actually doing (in near real time), you can target the specific sources of energy waste, unplanned downtime, scrap, and rework that drive both cost and emissions.

Operational intelligence turns “we think this line is inefficient” into evidence: which assets are over-consuming power, which process steps run out of spec, and which shutdowns force restart cycles that burn extra fuel.

Even small improvements—shorter warm-up times, fewer idling hours, tighter setpoint control—add up across thousands of operating hours.

Three levers show up repeatedly:

It helps to separate three concepts:

Transparent metrics matter. Use clear baselines, document assumptions, and support claims with audit-ready evidence. That discipline helps avoid overclaiming impact—and makes real progress easier to scale across sites.

Choosing industrial software isn’t just a feature comparison—it’s a commitment to how work gets done across operations, maintenance, engineering, and IT.

A practical evaluation starts by aligning on the decisions you want the system to improve (for example: fewer unplanned outages, faster work orders, better energy performance) and the sites where you’ll prove it first.

Use a scorecard that reflects both the plant floor and enterprise needs:

Avoid “big bang” deployments. A phased approach reduces risk and builds credibility:

In practice, teams often underestimate how many “small” internal tools they’ll need during rollout—triage queues, exception reviews, work-order enrichment forms, approval workflows, and simple portals that connect OT signals to IT systems. Platforms like Koder.ai can help here by letting teams quickly build and iterate on these supporting web apps via chat, then integrate them with existing APIs—without waiting for a full custom development cycle.

Industrial software succeeds when frontline teams trust it. Budget time for role-based training, updated procedures (who acknowledges alerts, who approves work orders), and incentives that reward data-driven behavior—not just firefighting.

If you’re mapping options, it can help to review a vendor’s packaged use cases under /solutions, understand commercial models on /pricing, and talk through your environment via /contact.

Industrial tech is moving from “connected equipment” to “connected outcomes.” The direction is clear: more automation on the shop floor, more operational data available to business teams, and faster feedback loops between planning and execution.

Instead of waiting for weekly reports, organizations will expect near-real-time visibility into production, energy use, quality, and asset health—and then act on it with minimal manual handoffs.

Automation will expand beyond control systems into decision workflows: scheduling, maintenance planning, inventory replenishment, and exception management.

At the same time, data sharing is getting broader—but also more selective. Companies want to share the right data with the right partners (OEMs, contractors, utilities, logistics providers) without exposing sensitive process details.

That pushes vendors and operators to treat data as a product: well-defined, permissioned, and traceable. Success will hinge on governance that feels practical for operations, not just compliance-driven for IT.

As organizations mix legacy equipment with new sensors and software, interoperability becomes the difference between scaling and stalling. Open standards and well-supported APIs reduce lock-in, shorten integration timelines, and let teams upgrade one part of the stack without rewriting everything else.

In plain terms: if you can’t easily connect assets, historians, ERP/EAM, and analytics tools, you’ll spend your budget on plumbing instead of performance.

Expect “AI copilots” designed for specific industrial roles—maintenance planners, reliability engineers, control room operators, and field technicians. These tools won’t replace expertise; they’ll summarize alarms, recommend actions, draft work orders, and help teams explain why a change is suggested.

This is also where “vibe-coding” platforms like Koder.ai fit naturally: they can accelerate the creation of internal copilots and workflow apps (for example, an incident summarizer or a maintenance-planning assistant) while still allowing teams to export source code, deploy, and iterate with snapshots and rollback.

Next, more sites will adopt autonomous optimization in bounded areas: automatically tuning setpoints within safe limits, balancing throughput vs. energy cost, and adjusting maintenance windows based on real condition data.

It refers to industries where software influences real-world operations—power grids, rail networks, factories, and utilities—so data quality and timing affect uptime, safety, and cost, not just reporting.

In these settings, data must be trusted, time-aligned, and connected to the real asset and operating conditions to support decisions that can’t wait.

Because operations can’t simply “update later.” Sensors can be noisy, networks can drop, and a bad or late decision can create scrap, downtime, or safety risk.

Industrial teams also need decisions to be explainable to operators, engineers, and regulators—not just statistically accurate.

OT (Operational Technology) runs the process: PLCs, SCADA, instrumentation, and safety practices that keep equipment stable.

IT (Information Technology) runs the business: ERP, EAM/CMMS, analytics, identity/access, and enterprise cybersecurity.

Convergence is making them share the right data safely so operational signals can trigger business workflows (work orders, inventory checks, scheduling).

Common issues include:

Fixing these basics often resolves “disagreeing dashboards” more than adding new BI tools.

Volume doesn’t tell you what to do unless you know:

Example: “8 mm/s vibration” is far more actionable when tied to a specific pump, line, operating load, and recent repair history.

A practical flow is:

The goal is decisions and follow-through, not more dashboards.

Use edge when you need:

Use centralized platforms (cloud/data center) when you need:

APM (Asset Performance Management) focuses on risk and reliability outcomes: detecting degradation, predicting failures, and recommending interventions.

EAM/CMMS is the system of record for executing and auditing maintenance: asset hierarchies, work orders, labor, parts, permits, and history.

Together, APM prioritizes what to do, and EAM ensures it gets planned, controlled, and completed.

A digital twin is a working model used to test “what if?” decisions—throughput, energy, wear, and constraints—before changing the real system.

To be credible, it needs both:

Plan for ongoing maintenance (model drift, sensor gaps, validation routines).

Start with controls that fit operational realities:

Also prepare for recovery: offline backups, practiced restores, defined priorities, and clear OT/IT responsibilities.