Jun 08, 2025·8 min

How ACID Guarantees Shape Reliable Transactional Systems

Learn how ACID guarantees affect database design and app behavior. Explore atomicity, consistency, isolation, durability, trade-offs, and real examples.

Learn how ACID guarantees affect database design and app behavior. Explore atomicity, consistency, isolation, durability, trade-offs, and real examples.

When you pay for groceries, book a flight, or move money between accounts, you expect the outcome to be unambiguous: either it worked, or it didn’t. Databases aim to provide that same certainty—even when many people use the system at once, servers crash, or networks hiccup.

A transaction is a single unit of work the database treats as one “package.” It might include multiple steps—subtracting inventory, creating an order record, charging a card, and writing a receipt—but it’s meant to behave as one coherent action.

If any step fails, the system should rewind to a safe point rather than leaving a half-finished mess.

Partial updates aren’t just technical glitches; they become customer support tickets and financial risk. For example:

These failures are hard to debug because everything looks “mostly correct,” yet the numbers don’t add up.

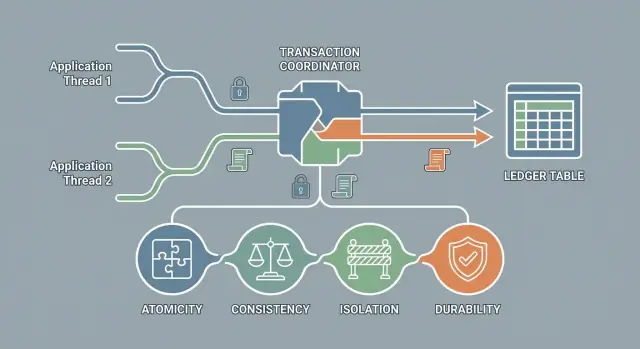

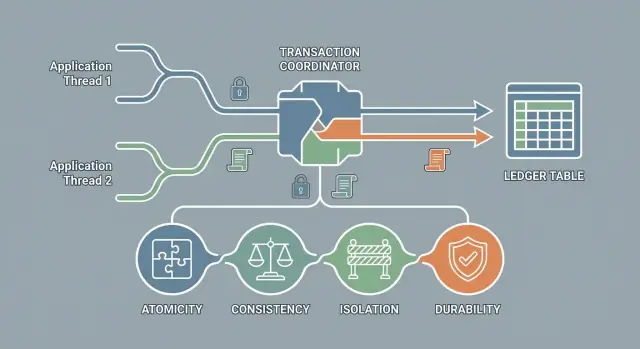

ACID is shorthand for four guarantees many databases can provide for transactions:

It’s not a specific database brand or a single feature you toggle; it’s a promise about behavior.

Stronger guarantees usually mean the database must do more work: extra coordination, waiting for locks, tracking versions, and writing to logs. That can reduce throughput or increase latency under heavy load. The goal isn’t “maximum ACID at all times,” but choosing guarantees that match your real business risks.

Atomicity means a transaction is treated as a single unit of work: it either finishes completely or has no effect at all. You never end up with “half an update” visible in the database.

Imagine transferring $50 from Alice to Bob. Under the hood, this typically involves at least two changes:

With atomicity, those two changes succeed together or fail together. If the system can’t safely do both, it must do neither. That prevents the nightmare outcome where Alice is charged but Bob doesn’t receive the money (or Bob receives it without Alice being charged).

Databases give transactions two exits:

A useful mental model is “draft vs. publish.” While the transaction is running, the changes are provisional. Only a commit publishes them.

Atomicity matters because failures are normal:

If any of these happens before the commit completes, atomicity ensures the database can roll back so partial work doesn’t leak into real balances.

Atomicity protects database state, but your application still must handle uncertainty—especially when a network drop makes it unclear whether a commit happened.

Two practical complements:

Together, atomic transactions and idempotent retries help you avoid both partial updates and accidental double-charges.

Consistency in ACID doesn’t mean “the data looks reasonable” or “all replicas match.” It means every transaction must take the database from one valid state to another valid state—according to the rules you define.

A database can only keep data consistent relative to explicit constraints, triggers, and invariants that describe what “valid” means for your system. ACID doesn’t invent these rules; it enforces them during transactions.

Common examples include:

order.customer_id must point to an existing customer.If these rules are in place, the database will reject any transaction that would violate them—so you don’t end up with “half-valid” data.

App-level validation is important, but it’s not sufficient on its own.

A classic failure mode is checking something in the app (“email is available”) and then inserting the row. Under concurrency, two requests can pass the check at the same time. A unique constraint in the database is what guarantees only one insert succeeds.

If you encode “no negative balances” as a constraint (or enforce it reliably within a single transaction), then any transfer that would overdraw an account must fail as a whole. If you don’t encode that rule anywhere, ACID can’t protect it—because there’s nothing to enforce.

Consistency is ultimately about being explicit: define the rules, then let transactions ensure those rules are never broken.

Isolation ensures transactions don’t step on each other. While one transaction is in progress, other transactions should not see half-finished work or accidentally overwrite it. The goal is simple: each transaction should behave as if it were running alone, even when many users are active at the same time.

Real systems are busy: customers place orders, support agents update profiles, background jobs reconcile payments—all at once. These actions overlap in time, and they often touch the same rows (an account balance, inventory count, or booking slot).

Without isolation, timing becomes part of your business logic. A “subtract stock” update could race with another checkout, or a report might read data mid-change and show numbers that never existed in a stable state.

Full “act like you’re alone” isolation can be expensive. It can reduce throughput, increase waiting (locks), or cause transaction retries. Meanwhile, many workflows don’t need the strictest protection—reading yesterday’s analytics, for example, can tolerate minor inconsistencies.

That’s why databases offer configurable isolation levels: you choose how much concurrency risk you’ll accept in exchange for better performance and fewer conflicts.

When isolation is too weak for your workload, you’ll run into classic anomalies:

Understanding these failure modes makes it easier to pick an isolation level that matches your product’s promises.

Isolation determines what other transactions you’re allowed to “see” while yours is still running. When isolation is too weak for a workload, you can get anomalies—behaviors that are technically possible but surprising to users.

Dirty read happens when you read data another transaction has written but not committed.

Scenario: Alex transfers $500 out of an account, the balance temporarily becomes $200, and you read that $200 before Alex’s transfer later fails and rolls back.

User outcome: a customer sees an incorrect low balance, a fraud rule triggers incorrectly, or a support agent gives the wrong answer.

Non-repeatable read means you read the same row twice and get different values because another transaction committed in between.

Scenario: You load an order total ($49.00), then refresh details a moment later and see $54.00 because a discount line was removed.

User outcome: “My total changed while I was checking out,” leading to mistrust or abandoned carts.

Phantom read is like non-repeatable read, but with a set of rows: a second query returns extra (or missing) rows because another transaction inserted/deleted matching records.

Scenario: A hotel search shows “3 rooms available,” then during booking the system rechecks and finds none because new reservations were added.

User outcome: double booking attempts, inconsistent availability screens, or overselling inventory.

Lost update occurs when two transactions read the same value and both write back updates, with the later write overwriting the earlier one.

Scenario: Two admins edit the same product price. Both start from $10; one saves $12, the other saves $11 last.

User outcome: someone’s change disappears; totals and reports are wrong.

Write skew happens when two transactions each make a change that is individually valid, but together violate a rule.

Scenario: Rule: “At least one on-call doctor must be scheduled.” Two doctors independently mark themselves off-call after checking that the other is still on-call.

User outcome: you end up with zero coverage, despite each transaction “passing” its checks.

Stronger isolation reduces anomalies but can increase waiting, retries, and costs under high concurrency. Many systems choose weaker isolation for read-heavy analytics, while using stricter settings for money movement, booking, and other correctness-critical flows.

Isolation is about what your transaction is allowed to “see” while other transactions are running. Databases expose this as isolation levels: higher levels reduce surprising behavior, but can cost throughput or increase waiting.

Teams often pick Read Committed as a default for user-facing apps: good performance, and “no dirty reads” matches most expectations.

Use Repeatable Read when you need stable results inside a transaction (for example, generating an invoice from a set of line items) and you can tolerate some overhead.

Use Serializable when correctness is more important than concurrency (for example, enforcing complex invariants like “never oversell inventory”), or when you can’t easily reason about race conditions in application code.

Read Uncommitted is rare in OLTP systems; it’s sometimes used for monitoring or approximate reporting where occasional wrong reads are acceptable.

Names are standardized, but exact guarantees differ by database engine (and sometimes by configuration). Confirm with your database documentation and test the anomalies that matter to your business.

Durability means that once a transaction is committed, its results should survive a crash—power loss, process restart, or a sudden machine reboot. If your app tells a customer “payment successful,” durability is the promise that the database won’t “forget” that fact after the next failure.

Most relational databases achieve durability with write-ahead logging (WAL). At a high level, the database writes a sequential “receipt” of changes to a log on disk before it considers the transaction committed. If the database crashes, it can replay the log during startup to restore the committed changes.

To keep recovery time reasonable, databases also create checkpoints. A checkpoint is a moment where the database ensures enough of the recent changes are written into the main data files, so recovery doesn’t need to replay an unbounded amount of log history.

Durability is not a single on/off switch; it depends on how aggressively the database forces data to stable storage.

fsync) before confirming commit. This is safer, but can add latency.The underlying hardware matters too: SSDs, RAID controllers with write caches, and cloud volumes can behave differently under failure.

Backups and replication help you recover or reduce downtime, but they’re not the same as durability. A transaction can be durable on the primary even if it hasn’t reached a replica yet, and backups are typically point-in-time snapshots rather than commit-by-commit guarantees.

When you BEGIN a transaction and later COMMIT, the database coordinates many moving parts: who can read which rows, who can update them, and what happens if two people try to change the same record at once.

A key “under the hood” choice is how to handle conflicts:

Many systems blend both ideas depending on workload and isolation level.

Modern databases often use MVCC (Multi-Version Concurrency Control): instead of keeping only one copy of a row, the database keeps multiple versions.

This is a big reason some databases handle lots of reads and writes concurrently with less blocking—though write/write conflicts still need resolution.

Locks can lead to deadlocks: Transaction A waits for a lock held by B, while B waits for a lock held by A.

Databases typically resolve this by detecting the cycle and aborting one transaction (a “deadlock victim”), returning an error so the application can retry.

If ACID enforcement is creating friction, you’ll often see:

These symptoms often mean it’s time to revisit transaction size, indexing, or which isolation/locking strategy fits the workload.

ACID guarantees aren’t just database theory—they influence how you design APIs, background jobs, and even UI flows. The core idea is simple: decide which steps must succeed together, then wrap only those steps in a transaction.

A good transactional API usually maps to a single business action, even if it touches multiple tables. For example, a /checkout operation might: create an order, reserve inventory, and record a payment intent. Those database writes should typically live in one transaction so they commit together (or roll back together) if any validation fails.

A common pattern is:

This keeps atomicity and consistency while avoiding slow, fragile transactions.

Where you place transaction boundaries depends on what “one unit of work” means:

ACID helps, but your application must still handle failures correctly:

Avoid long transactions, calling external APIs inside a transaction, and user think time inside a transaction (for example, “lock cart row, ask user to confirm”). These increase contention and make isolation conflicts far more likely.

If you’re building a transactional system quickly, the biggest risk is rarely “not knowing ACID”—it’s accidentally scattering one business action across multiple endpoints, jobs, or tables without a clear transaction boundary.

Platforms like Koder.ai can help you move faster while still designing around ACID: you can describe a workflow (for example, “checkout with inventory reservation and payment intent”) in a planning-first chat, generate a React UI plus a Go + PostgreSQL backend, and iterate with snapshots/rollback if a schema or transaction boundary needs to change. The database still enforces the guarantees; the value is in speeding up the path from a correct design to a working implementation.

A single database can usually deliver ACID guarantees within one transaction boundary. Once you spread work across multiple services (and often multiple databases), those same guarantees become harder to keep—and more expensive when you try.

Strict consistency means every read sees the “latest committed truth.” High availability means the system keeps responding even when parts are slow or unreachable.

In a multi-service setup, a temporary network problem can force a choice: block or fail requests until every participant agrees (more consistent, less available), or accept that services may be briefly out of sync (more available, less consistent). Neither is “always right”—it depends on what mistakes your business can tolerate.

Distributed transactions require coordination across boundaries you don’t fully control: network delays, retries, timeouts, service crashes, and partial failures.

Even if every service is correct, the network can create ambiguity: did the payment service commit but the order service never received the acknowledgment? To resolve that safely, systems use coordination protocols (like two-phase commit), which can be slow, reduce availability during failures, and add operational complexity.

Sagas break a workflow into steps, each committed locally. If a later step fails, earlier steps are “undone” using compensating actions (for example, refund a charge).

Outbox/inbox patterns make event publishing and consumption reliable. A service writes business data and an “event to publish” record in the same local transaction (outbox). Consumers record processed message IDs (inbox) to handle retries without duplicating effects.

Eventual consistency accepts short windows where data differs between services, with a clear plan for reconciliation.

Relax guarantees when:

Control risk by defining invariants (what must never be violated), designing idempotent operations, using timeouts and retries with backoff, and monitoring for drift (stuck sagas, repeated compensations, growing outbox tables). For truly critical invariants (for example, “never overspend an account”), keep them within a single service and a single database transaction where possible.

A transaction can be “correct” in a unit test and still fail under real traffic, restarts, and concurrency. Use this checklist to keep ACID guarantees aligned with how your system behaves in production.

Start by writing down what must always be true (your data invariants). Examples: “account balance never goes negative,” “order total equals sum of line items,” “inventory can’t drop below zero,” “a payment is linked to exactly one order.” Treat these as product rules, not database trivia.

Then decide what must be inside one transaction versus what can be deferred.

Keep transactions small: touch fewer rows, do less work (no external API calls), and commit quickly.

Make concurrency a first-class test dimension.

If you support retries, add an explicit idempotency key and test “request repeated after success.”

Watch indicators that your guarantees are becoming expensive or fragile:

Alert on trends, not just spikes, and tie metrics back to the endpoints or jobs causing them.

Use the weakest isolation that still protects your invariants; don’t “max it out” by default. When you need strict correctness for a small critical section (money movement, inventory decrement), narrow the transaction to just that section and keep everything else outside it.

ACID is a set of transactional guarantees that help databases behave predictably under failures and concurrency:

A transaction is a single “unit of work” the database treats as one package. Even if it performs multiple SQL statements (e.g., create order, decrement inventory, record payment intent), it has only two outcomes:

Because partial updates create real-world contradictions that are expensive to fix later—for example:

ACID (especially atomicity + consistency) prevents these “half-finished” states from becoming visible as truth.

Atomicity ensures the database never exposes a “half-complete” transaction. If anything fails before commit—app crash, network drop, DB restart—the transaction is rolled back so earlier steps don’t leak into persistent state.

In practice, atomicity is what makes multi-step changes (like a transfer that updates two balances) safe.

You can’t always know whether a commit happened if the client loses the response (e.g., network timeout right after commit). Combine ACID transactions with:

This prevents both partial updates and accidental double-charges/double-writes.

In ACID, “consistency” means the database moves from one valid state to another according to rules you define—constraints, foreign keys, uniqueness, and checks.

If you don’t encode a rule (e.g., “balance can’t go below zero”), ACID can’t enforce it automatically. The database needs explicit invariants to protect.

App validation improves UX and can enforce complex rules, but it can fail under concurrency (two requests pass the same check at the same time).

Database constraints are the final gatekeeper:

Use both: validate early in the app, enforce definitively in the database.

Isolation controls what your transaction can observe while others run. Weak isolation can produce anomalies such as:

Isolation levels let you trade performance for protection against these anomalies.

A common, practical baseline is Read Committed for many OLTP apps because it prevents dirty reads with good performance. Move upward when needed:

Always confirm behavior in your specific database engine because details vary.

Durability means once the database confirms a commit, the change will survive crashes. Typically this is implemented via write-ahead logging (WAL) and checkpoints.

Be aware of configuration trade-offs:

Backups and replication help recovery/availability, but they’re not the same guarantee as durability.