Mar 25, 2025·8 min

How Adobe Built High Switching Costs in Creative Workflows

A practical look at how Adobe workflows, file formats, and subscriptions create high switching costs—and how teams can reduce lock-in without chaos.

A practical look at how Adobe workflows, file formats, and subscriptions create high switching costs—and how teams can reduce lock-in without chaos.

High switching costs are the extra time, money, and risk a team absorbs when it tries to move from one toolset to another—even if the new tools are cheaper or “better.” It’s not just the price of new licenses. It’s the rework, the retraining, the broken handoffs, and the uncertainty during a live production schedule.

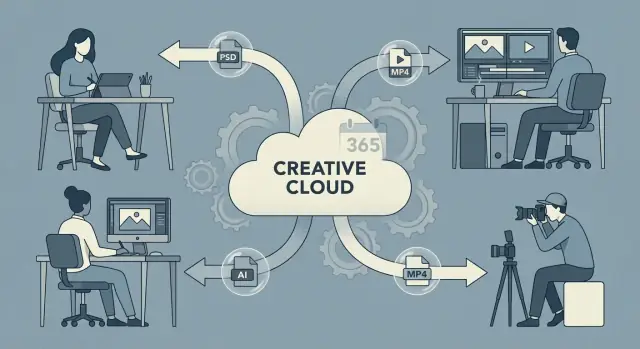

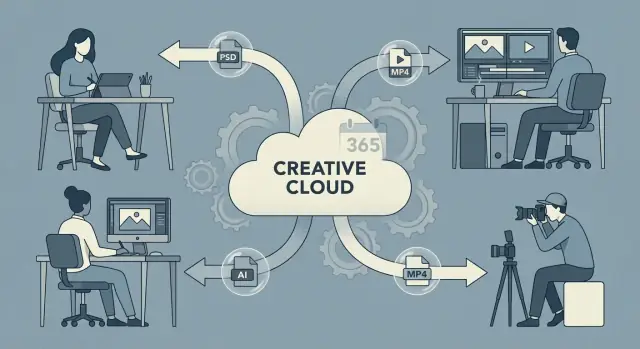

An ecosystem is the connected set of apps, file types, plugins, shared assets, and habits that work together. Adobe Creative Cloud isn’t only a collection of programs; it’s a web of defaults that quietly shapes how work gets made and shared.

Creative teams value continuity because their work isn’t only ideas—it’s also accumulated decisions:

When those building blocks move cleanly from project to project, teams stay fast and consistent. When they don’t, productivity drops and quality can drift.

This article looks at how Adobe built switching costs through three reinforcing pillars:

Workflows: established ways teams edit, design, review, and deliver

Formats: files like PSD, AI, and PDF acting as working documents—not just exports

Subscriptions: recurring pricing that changes how “leaving” is calculated over time

This is an analysis of how lock-in can form in creative production, not a product endorsement. Many teams succeed with creative software alternatives—but the real challenge is usually the hidden cost of changing everything around the software, not just the app icon on someone’s dock.

A creative “project” rarely stays a single file handled by one person. In most teams, it quickly becomes a pipeline: a repeatable sequence that turns ideas into assets that ship on time, every time.

A common flow looks like this:

Concept → design → review → delivery → archive

At each step, work shifts format, owner, and expectations. A rough idea becomes a draft layout, then a polished asset, then a packaged deliverable, then something searchable months later.

Dependencies form at the handoffs—when one person needs to open, edit, export, comment on, or reuse what someone else made.

Each handoff adds a simple question that matters: Can the next person pick this up instantly without rework? If the answer depends on a particular tool, file type, plugin, or export preset, the pipeline becomes “sticky.”

Consistency isn’t about preference—it’s about speed and risk.

When everyone uses the same tools and conventions, teams spend less time translating work (rebuilding layers, re-exporting assets, hunting missing fonts, re-linking images). Fewer translations also means fewer mistakes: wrong color profiles, mismatched dimensions, outdated logos, or exports that look fine on one machine but not in production.

Teams gradually standardize on templates, naming conventions, shared export settings, and “the way we do it.” Over time, those standards harden into habits.

Habits become dependencies when deadlines, approvals, and reuse assume the same inputs every time. That’s the moment a single project stops being portable—and the pipeline starts defining what tools the team can realistically use.

Creative teams rarely choose a tool once—they choose it every day, by habit. Over time, Adobe apps become the default not because people love change-resistant software, but because the tooling quietly optimizes itself around how the team works.

Once a team has a set of reusable building blocks—color palettes, brushes, character styles, presets, LUTs, export settings, and naming conventions—work speeds up across projects. A consistent retouching look can be applied in Lightroom and Photoshop. Typography rules can travel from a layout to marketing variations.

Even when files don’t literally share the same settings, teams standardize them and expect them to behave consistently.

When UI patterns and keyboard shortcuts feel familiar across apps, switching tasks is smoother: select, mask, align, transform, export. That consistency turns into muscle memory.

A designer can jump between Photoshop, Illustrator, InDesign, and After Effects without re-learning basic interactions, which makes the whole stack feel like one extended workspace.

Actions, templates, scripts, and batch processes often start small (“just to speed up exports”), then grow into a production layer. A team might build:

That saved time is real—and it’s why workflow investment accumulates over years. Replacing software isn’t only about features; it’s about rebuilding the invisible machinery that keeps production moving.

File formats don’t just store artwork—they decide whether someone else can continue the work or only receive the result. That distinction is a major reason Adobe projects tend to stay inside Adobe.

An exported file (like a flattened PNG) is great for delivery, but it’s basically a dead end for production. You can place it, crop it, and maybe retouch it, but you can’t reliably change the underlying decisions—individual layers, masks, type settings, or non-destructive effects.

Native formats like PSD (Photoshop) and AI (Illustrator) are designed as working files. They preserve the structure that makes iteration fast: layers and groups, smart objects, masks, blend modes, appearance stacks, embedded/linked assets, and editable text.

Even when there isn’t a literal “history,” the file often contains enough structured state (adjustment layers, live effects, styles) to feel history-like: you can step back, tweak, and re-export without rebuilding.

Other apps can sometimes open or import PSD/AI, but “opens” doesn’t always mean “faithfully editable.” Common failure points include:

The result is hidden rework: teams spend time fixing conversions instead of designing.

Formats like PDF and SVG are best thought of as interchange: they’re excellent for sharing, proofing, printing, and certain handoffs. But they don’t consistently preserve app-specific editability (especially complex effects or multi-artboard project structure).

So many teams end up sharing PDFs for review—while keeping PSD/AI as the “source of truth,” which quietly reinforces the same toolchain.

A .PSD, .AI, or even a “simple” .INDD layout often looks self-contained: open it, tweak it, export it. In practice, one design file can behave more like a mini-project with its own supply chain.

That’s where switching costs hide—because the risk isn’t “can another tool open the file?” but “will it render the same, print the same, and stay editable?”

Many documents rely on parts that live elsewhere, even if the file opens without errors at first:

If any of these are broken, the document may still open—but it opens “wrong,” which is harder to detect than a clear error.

Color management is a dependency you don’t see on the canvas. A file might assume a specific ICC profile (sRGB, Adobe RGB, or a print CMYK profile). When another tool or another computer uses different defaults, you can get:

The problem is less about “supporting CMYK” and more about consistent profile handling across import, preview, and export.

Type is rarely portable.

A document may depend on specific fonts (including licensed families or variable fonts), kerning pairs, OpenType features, and even the text engine that defines line breaking and glyph shaping. Substitute a font, and the layout reflows: line lengths change, hyphenation shifts, and captions jump pages.

Handoff often requires collecting fonts, linked images, and sometimes color settings into one folder. It sounds straightforward, but teams frequently miss:

That’s how a single design file becomes a web of dependencies—and why moving away from Adobe can feel less like opening a file elsewhere and more like reconstructing a project.

For many creative teams, the biggest time-saver isn’t a fancy filter—it’s a shared library. Once a team starts relying on centralized assets, switching tools stops being “export some files” and becomes “rebuild how we work.”

Adobe’s Libraries and asset panels make common elements instantly reusable: logos, icons, product shots, color swatches, character styles, motion presets, and even approved copy snippets.

Designers stop hunting through folders or asking in chat, because the “approved” pieces sit right inside the apps they already use. The payoff is real: fewer re-created assets, fewer off-brand variations, and less time spent packaging files for others.

That convenience is also the hook—when the library is the workflow, leaving means losing that built-in retrieval and reuse.

Over time, libraries turn into a living brand system. Teams centralize:

As the library becomes the single source of truth, it quietly replaces informal style guides with something more direct: assets people can drag-and-drop without thinking.

Many teams adopt a simple habit: “If it’s in the library, it’s current.” The latest hero image, updated logo, or refreshed button style isn’t emailed around—it’s updated once and reused everywhere.

That reduces coordination overhead, but it also makes leaving hard: you’re not just moving files, you’re moving a versioning system and a trust model.

Even if you can export SVGs, PNGs, or PDFs, you may not be able to export the behavior of the library: naming conventions, permissions, update workflows, and where people instinctively go to grab approved assets.

Rebuilding that in a new tool takes planning, training, and a transition period where “latest” is suddenly unclear again.

Creative work rarely ships after one person “finishes” a file. It moves through a review loop: someone requests changes, someone annotates details, someone approves, and the cycle repeats.

The more a tool makes that loop feel effortless, the more it becomes the default—even when switching tools might reduce licensing costs.

Modern review isn’t just “looks good” in an email. Teams rely on precise feedback: pinned comments on a specific frame, annotations that reference a layer or timecode, side-by-side comparisons, and an audit trail of what changed.

When that feedback is tied to the same ecosystem as the source files (and the same accounts), the loop tightens:

A simple share link is a quiet switching-cost generator. Clients don’t need to download a giant file, install a viewer, or worry about “which version is current.” They open a preview, leave feedback, and move on.

That convenience makes the collaboration channel feel like part of the deliverable—and it nudges everyone to stay in the same stack because it’s the path of least resistance.

Access control also locks habits in place. Who can view versus comment? Who can export? Can external users see everything or only a specific preview?

When a team has established a working pattern around permissions—especially with freelancers and agencies—changing tools means rethinking governance, not just interfaces.

A gentle caution: avoid relying on a single review channel as the “source of truth.” When feedback lives in one system, you can lose context during a tool change, a contract handoff, or even an account transition. Exportable summaries, agreed naming conventions, and periodic decision notes keep reviews portable without slowing production.

Adobe Creative Cloud isn’t priced like a “buy once, use forever” tool. Subscription access becomes an ongoing requirement for staying compatible with your own workflow: opening current client files, exporting in expected formats, syncing libraries, and using the same fonts and plugins everyone else has.

Subscriptions are easier to approve because they look like operating expenses: a per-seat cost that can be forecasted and tied to a team budget.

That predictability is real—especially for companies that hire contractors, scale teams up and down, or need standardized tooling across departments. But the flip side is the long-term total cost.

Over years, the “rent” can exceed what teams mentally compare it to (a one-time license), and the exit math gets tricky: switching isn’t just about learning new tools, it’s about justifying why you’d pay twice during a transition period.

When a subscription ends, the impact isn’t limited to missing updates. Practical consequences can include:

Even when files remain on disk, a lapse can turn “we’ll revisit this later” into “we can’t work on this at all,” especially for teams maintaining long-lived assets.

In businesses, subscriptions aren’t personal choices—they’re procurement systems. Seats are assigned, reclaimed, and audited. Onboarding often includes approved templates, shared libraries, SSO, and device policies.

Renewals become calendar events with budget owners, vendor relationships, and sometimes multi-year commitments. All of that administration creates momentum: once a company standardizes on Adobe, leaving means redoing not only tools, but purchasing, training, and governance—at the same time.

A big part of Adobe Creative Cloud’s stickiness doesn’t come from the core apps alone—it comes from everything teams pile on top of them. Plugins, scripts, panels, and small extensions often start as “nice-to-haves,” but they quickly become the shortcuts that keep production moving.

In many teams, the most valuable work isn’t the glamorous stuff—it’s the repetitive work: exporting dozens of sizes, renaming layers, generating thumbnails, cleaning up files, packaging deliverables for clients, or preparing handoff assets.

Add-ons can turn these tasks into one-click actions. Once a team relies on that speed, switching tools isn’t just “learning a new interface.” It means recreating the same automation (or accepting slower throughput), plus re-training everyone on a different set of behaviors.

Creative apps rarely stand alone. They connect to stock asset sources, font services, cloud storage, review and approval systems, asset libraries, and other third-party services that sit upstream and downstream from design.

When those connections are built around one platform—through official integrations, shared login flows, or embedded panels—the creative tool becomes a hub. Moving away isn’t only replacing the editor; it’s rewiring how assets enter the team and how deliverables leave it.

Teams often build internal scripts, templates, and presets tailored to their brand and process. Over time, those homegrown tools encode assumptions specific to Adobe file structures, layer naming, export settings, and library conventions.

The compounding effect is the real multiplier: the more add-ons, integrations, and internal helpers you accumulate, the more switching becomes a full ecosystem migration—not a simple software swap.

Switching tools isn’t only a file or licensing decision—it’s a people decision. Many creative teams stay with Adobe Creative Cloud because the human cost of changing is predictable, high, and easy to underestimate.

Job descriptions for designers, editors, and motion artists often list Photoshop, Illustrator, InDesign, After Effects, or Premiere as baseline requirements. Recruiters screen for those keywords, portfolios are built around them, and candidates signal competence by naming them.

That creates a quiet loop: the more common Adobe is in the market, the more hiring processes treat it as table stakes. Even teams open to alternatives may revert because they need someone productive on day one.

Adobe benefits from decades of courses, tutorials, certifications, and classroom programs. New hires frequently arrive with familiar shortcuts, panel names, and workflows.

When you switch, you’re not only teaching a new interface—you’re rewriting the shared vocabulary the team uses to collaborate (“send me the PSD,” “make it a smart object,” “package the InDesign file”).

Most teams have practical documentation that only makes sense in the current stack:

Those playbooks aren’t glamorous, but they keep production moving. Migrating them takes time, and inconsistencies create real risk.

The strongest lock-in often sounds reasonable: fewer questions, fewer mistakes, faster onboarding. Once a team believes Adobe is the safest common denominator, switching starts to feel like choosing friction—regardless of whether the alternative is cheaper or better.

Teams usually start talking about leaving Adobe when something “breaks” in the business, not because they dislike the tools.

Pricing changes are the obvious spark, but they’re rarely the only one. Common triggers include new requirements (more video, more social variants, more localization), performance issues on older machines, platform constraints (remote contractors, mixed OS fleets), or a security/compliance push that forces tighter control over assets and access.

When evaluating alternatives, it helps to score four things:

Many teams underestimate the “time to normal,” because production work continues while people learn new habits.

Before committing to a migration, run a short pilot: pick one campaign or content type, recreate the full cycle (create → review → export → archive), and measure revision count, turnaround time, and failure points.

You’re not trying to “win a debate”—you’re mapping hidden dependencies early, while it’s still cheap to change course.

Reducing lock-in doesn’t have to mean ripping out your stack or forcing everyone onto new tools overnight. The goal is to keep output flowing while making your work easier to move, audit, and reuse later.

Keep “editable” source files (PSD/AI/AE, etc.) where they add value, but shift routine handoffs to formats other tools can reliably open.

This reduces the number of moments where a project must be opened in one vendor’s app to move forward.

Treat archiving as a deliverable, not an afterthought. For each project, save:

If you can’t re-open a file in five years, you can still re-use the output and understand what was shipped.

Run a small team in parallel for 2–4 weeks: same briefs, same deadlines, different toolchain. Track what breaks (fonts, templates, review cycles, plugins) and what improves.

You’ll get real data instead of guesses.

Write down:

Switching costs aren’t unique to design software. Product and engineering teams experience the same gravity around codebases, frameworks, deployment pipelines, and account-bound collaboration.

If you’re building internal tools to support creative production (asset portals, campaign managers, review dashboards), platforms like Koder.ai can help you prototype and ship web/back-end/mobile apps from a chat interface—while keeping portability in mind. Features like source code export and snapshots/rollback can reduce long-term risk by making it easier to audit what’s running and migrate later if requirements change.

For next steps, collect requirements and compare options, then use decision aids like /pricing and related guides on /blog.

High switching costs are the extra time, money, and risk your team absorbs when moving to a new toolset—not just new license fees. Typical costs include retraining, rebuilding templates/automation, fixing file-conversion issues, disrupted review loops, and slowed throughput during active production.

Because creative work is an accumulation of decisions stored in working files and habits: layers, masks, typography rules, presets, shortcuts, templates, and export routines. When continuity breaks, teams spend time translating and re-checking work, which increases turnaround time and the chance of production mistakes.

Score options across four dimensions:

Use a pilot to replace assumptions with measured failure points.

Native formats (like PSD/AI) are working documents that preserve structure—editable text, layer effects, masks, smart objects, appearances. Interchange formats (PDF/SVG/PNG) are great for sharing and delivery, but they often don’t preserve every editable decision reliably.

A practical rule: use native files for creation and iteration, interchange formats for review and handoff.

Common break points include:

Before migrating, test your real files: the templates, the “hairy” PSDs, the print PDFs, and the assets that re-open repeatedly over months.

Create a repeatable “handoff package” checklist:

README with owner, date, tool version, and known gotchasThe goal is: the file opens renders correctly later, even if tools change.

Libraries lock in more than files—they lock in “where people go for the latest.” To migrate with less pain:

Plan for a transition period where “latest” must be explicitly communicated.

Review loops become sticky when comments, approvals, and version history live inside one ecosystem. To keep reviews more portable:

This reduces the chance that a tool change strands critical feedback context.

A lapse can block practical work even if files still exist:

If you’re risk-sensitive, ensure you have exported deliverables and a documented archive before changing subscription status.

Start with a controlled pilot instead of a full cutover:

This approach surfaces hidden dependencies while the cost of reversing course is still low.