Jul 23, 2025·8 min

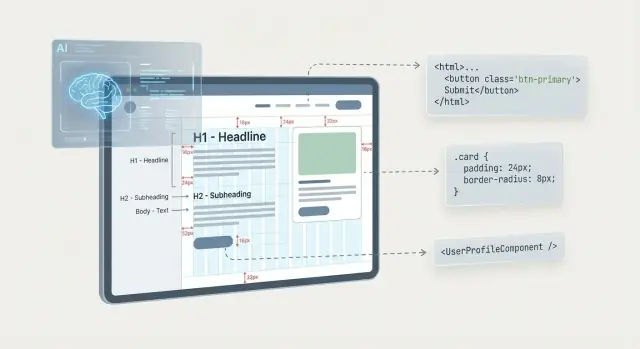

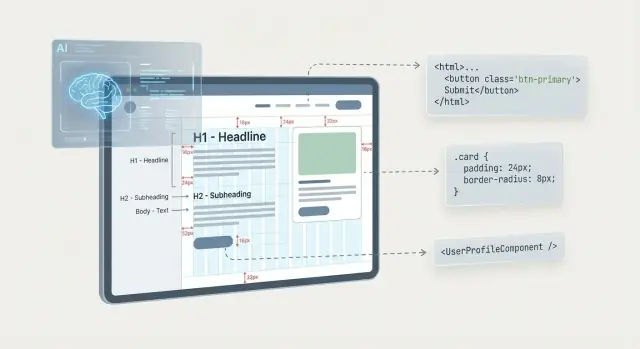

How AI Reads Layout and Intent to Turn Designs into UI Code

Learn how AI infers layout, hierarchy, and user intent from designs, then generates UI code—plus limits, best practices, and review tips.

Learn how AI infers layout, hierarchy, and user intent from designs, then generates UI code—plus limits, best practices, and review tips.

“Design to code” AI translates a visual design idea—usually a Figma frame or a screenshot—into runnable UI code. The point isn’t “perfect code”; it’s a usable first draft that captures structure, styling, and basic behavior so a human can refine it.

At its core, the system maps what it can observe to how UIs are typically constructed.

AI can infer common patterns: a row of icons is likely a toolbar; a stacked label + input is likely a form field; consistent styling suggests a reusable component. It may also guess responsive behavior based on constraints and spacing.

But you usually must specify what pixels can’t guarantee: real component names, design tokens (colors/type scales), states (hover/disabled/error), breakpoints, data rules, and actual interactions (validation, navigation targets, analytics).

Treat the output as a starting point. Expect to review structure, replace ad-hoc styles with tokens, align to your component library, and iterate. “Design to code” is acceleration—not automation that removes the need for design and engineering judgment.

AI can’t infer product rules from a “pretty screen.” It works from the evidence you provide—some inputs describe pixels, others describe structure. That difference often determines whether you get clean UI code or brittle absolute positioning.

A screenshot is the thinnest input: it contains colors and shapes, but no explicit facts about what’s a button vs. a label, what’s reusable, or how the layout should adapt.

From pixels alone, AI must guess boundaries (where one element ends and another begins), text styles, spacing rules, and even whether a “card” is one component or several separate pieces. It also can’t infer constraints—so responsive behavior is mostly speculation.

When AI can access the design file (or an export that preserves structure), it gains crucial metadata: frames, groups, layer names, auto-layout settings, constraints, and text/style definitions.

This is where layout becomes more than geometry. For example, a Figma frame with Auto Layout communicates intent like “stack these items vertically with 16px gap” far better than any screenshot. Consistent layer naming also helps map elements to UI roles (e.g., “Primary Button,” “Nav Item,” “Input/Error”).

A connected design system reduces guesswork. Tokens (colors, spacing, typography) let AI generate code that references a shared source of truth instead of hard-coded values. Published components (buttons, fields, modals) provide ready-made building blocks and clearer boundaries for reuse.

Even small conventions—like naming variants (Button/Primary, Button/Secondary) and using semantic tokens (text/primary) instead of #111111—improve component mapping.

Specs add the “why” behind the UI: hover behavior, loading and empty states, validation rules, keyboard behavior, and error messaging.

Without this, AI tends to generate a static snapshot. With it, output can include interaction hooks, state handling, and more realistic component APIs—closer to something a team can ship and maintain.

Design-to-code tools don’t perceive a screen like a person; they try to explain every layer as layout rules: rows, columns, containers, and spacing. The clearer those rules are, the less the output relies on brittle positioning.

Most models start by looking for repeated alignment and equal gaps. If several elements share the same left edge, baseline, or center line, AI often treats them as a column or grid track. Consistent spacing (e.g., 8/16/24px patterns) hints that layout can be expressed with stack gaps, grid gutters, or tokenized spacing.

When spacing varies slightly (15px here, 17px there), AI may conclude the layout is “manual” and fall back to absolute coordinates to preserve pixel-perfect distances.

AI also searches for visual “enclosure”: backgrounds, borders, shadows, and padding-like gaps that suggest a container. A card with a background and internal padding is a clear signal for a parent element with children.

From there it often maps structure into primitives such as:

Clean grouping in the design file helps distinguish parents from siblings.

If the design includes constraints (pinning, hugging, fill), AI uses them to decide what stretches and what stays fixed. “Fill” elements typically become flexible widths (e.g., flex: 1), while “hug” maps to content-sized elements.

Absolute positioning usually appears when the model can’t confidently express relationships with flow layouts—often due to inconsistent spacing, overlapping layers, or misaligned elements. It can look correct at one screen size but break responsiveness and text resizing.

Using a small spacing scale and aligning to a clear grid dramatically increases the chance the AI produces clean flex/grid code instead of coordinates. Consistency isn’t just aesthetics—it’s a machine-readable pattern.

AI doesn’t “understand” hierarchy; it infers importance from patterns that usually signal it. The more clearly your design communicates those signals, the more likely the generated UI matches your intent.

Typography is one of the strongest clues. Larger type, heavier weight, higher contrast color, and more generous line height typically indicate higher priority.

For example, a 32px bold title above a 16px regular paragraph is a clear “heading + body” pattern. Where it gets tricky is when styles blur—e.g., two text blocks differ by only 1–2px or use the same weight with different colors. In those cases, AI may label both as plain text or choose the wrong heading level.

Hierarchy is also inferred from spatial relationships. Elements that are closer together, aligned, and separated from other content by whitespace are treated as a group.

Common backgrounds (cards, panels, tinted sections) act like visual brackets: AI often interprets them as containers such as a section, aside, or a component wrapper. Uneven padding or inconsistent spacing can cause accidental regrouping—like a button being attached to the wrong card.

Repeated patterns—identical cards, list items, rows, or form fields—are strong evidence of a reusable component. Even small differences (icon size, corner radius, text style) may lead AI to generate multiple one-off versions instead of a single component with variants.

Buttons communicate intent through size, fill, contrast, and position. A filled button with strong contrast is usually treated as the primary action; outlined or text buttons become secondary. If two actions look equally emphasized, AI may guess incorrectly which one is “primary.”

Finally, AI tries to map hierarchy into semantics: headings (h1–h6), grouped regions (section), and meaningful clusters (like “product details” vs. “purchase actions”). Clear typographic steps and consistent grouping make this translation far more reliable.

Models predict intent by matching what they see to patterns learned from many UIs: common shapes, labels, iconography, and placement conventions.

Certain arrangements strongly suggest specific components. A horizontal strip at the top with a logo on the left and text items on the right is likely a navigation bar. A row of equal-width items with one highlighted often maps to tabs. Repeated boxes with an image, title, and short text read as cards. Dense grids with aligned headers and rows often become tables.

These guesses matter because they affect structure: a “tab” implies selected state and keyboard navigation, while a “row of buttons” might not.

AI looks for cues that typically indicate interaction:

From there it assigns behaviors: click, open menu, navigate, submit, expand/collapse. The more the design differentiates interactive from static elements, the more accurate the output.

If the design shows multiple variants—hover, active/selected, disabled, error, loading—AI can map them to stateful components (e.g., disabled buttons, validation messages, skeleton loaders). When states aren’t explicit, AI may omit them.

Ambiguity is common: is a card clickable or informational? Is a chevron decorative or a disclosure control? In those cases, clarify through naming, annotations, or separate frames that demonstrate the interaction.

Once an AI has a plausible read of layout, the next step is translating “what it looks like” into “what it is”: semantic HTML, reusable components, and consistent styling.

Most tools map design layers and groups into a DOM tree: frames become containers, text layers become headings/paragraphs, and repeated items become lists or grids.

When intent is clear, AI may attach better semantics—e.g., a top bar becomes a <header>, a logo and links become a <nav>, and a clickable card becomes an <a> or <button>. ARIA roles can sometimes be inferred (like role="dialog" for a modal), but only when the pattern is unambiguous; otherwise, safer output is plain HTML plus TODOs for accessibility review.

To avoid generating a single giant file, AI tries to cut UI into primitives:

Common signals for a “component” are repetition, consistent padding/typography, and a grouped clickable area. Common failure modes are over-fragmentation (too many tiny components) or under-fragmentation (everything hardcoded once).

The generator usually picks one approach based on the target stack or its defaults:

High-quality output leans on design tokens—colors, spacing, radius, shadows—so the code stays consistent when the design evolves. A strict pixel match often produces one-off values (e.g., 13px gaps, near-identical grays) that look right but are hard to maintain.

A practical balance is: preserve hierarchy and spacing rhythm, then normalize into tokens and components you can reuse (and refactor further in the review step—see /blog/how-to-review-and-refactor-generated-ui-code).

Design files often look “finished” because they’re drawn at a few fixed frame sizes (like 1440 and 375). Code can’t assume that. A design-to-code tool must decide how the UI behaves across in-between widths, using a mix of clues and defaults.

If your design includes multiple versions of the same screen (desktop/tablet/mobile) and the structure is consistent, AI can align them and infer where layout rules change. Without variants, it typically falls back to common breakpoints and treats the frame size as the “base,” which can lead to awkward jumps.

AI looks for patterns: repeated cards in a grid, equal spacing, and alignment. From that it may decide that a 3-column grid becomes 2 columns, then 1. It struggles when the design relies on manual nudges—elements that look aligned but aren’t truly consistent—because it can’t tell whether that was intentional.

Most designs use short, tidy copy. Real products don’t. AI-generated UI code often sets fixed widths/heights or truncates too aggressively.

A quick sanity check is to test:

AI may preserve the pixel-perfect crop from the design, but responsive UIs need rules: keep aspect ratio, choose how to crop, and decide when images should scale down versus swap placement. If the design doesn’t specify this, expect “fill” behavior that crops important parts.

Before trusting the output, preview at very small widths, very large monitors, and in-between sizes. If anything overlaps, clips, or becomes unreadable, the issue is usually missing layout intent—not “bad code”—and it’s a signal to add clearer constraints in the design.

AI can convert pixels into UI code surprisingly well, but accessibility is where “looks right” often diverges from “works for everyone.” Because many requirements aren’t visible in a static frame, the model needs explicit signals.

Some accessibility-friendly choices do show up visually, and AI can often map them into better HTML:

Other requirements aren’t reliably visible:

Expect gaps like missing label/for connections, incorrect heading levels, clickable divs without keyboard support, weak focus styles, and icons without text alternatives.

h1 → h2 → h3).header, nav, main, footer) and aren’t duplicated.alt (or alt="" when decorative).Add a short spec when you have modals, drawers, complex forms, custom selects, drag-and-drop, or anything with non-trivial states. Even a few notes like “trap focus in modal,” “Esc closes,” and “announce inline errors” can dramatically improve generated UI code.

AI can produce UI code that looks close at first glance, but small interpretation errors add up quickly. Most issues come from “reasonable guesses” when the design doesn’t clearly encode rules.

A common complaint is mismatched spacing: buttons that feel slightly off, sections that breathe too much, or cards that look cramped. This happens when padding across similar elements is inconsistent, or when auto-layout/constraints are mixed with manual nudges. The model may infer a pattern (e.g., “16px everywhere”) and override exceptions—or preserve exceptions that were accidental.

Generated markup often has too many wrapper elements. Each inferred visual grouping becomes another <div>. The result is harder to style, harder to debug, and sometimes slower to render. You’ll notice it when a simple card becomes five nested containers just to align an icon and a title.

AI might split components too granularly (every label becomes its own component) or too monolithic (a whole screen becomes one component). The root cause is unclear boundaries: if repeated patterns aren’t identical, the model can’t confidently extract a shared component.

Typography often “drifts” because design text styles don’t map cleanly to code. Subtle differences in line height, letter spacing, or weight may be lost, and font fallbacks can change metrics between environments. That’s why a headline that fit in Figma suddenly wraps in code.

If hover, focus, error, loading, or empty states aren’t represented in the design, the AI rarely invents them. The UI may look correct in a static screenshot but fail as soon as users interact.

AI code generators don’t “see” your design the way a human does—they read a structured file full of layers, constraints, styles, and component instances. The cleaner that structure is, the less the model has to guess (and the fewer weird div soups you’ll untangle later).

Layer names are one of the strongest signals for intent and component mapping. Prefer consistent, descriptive patterns that match how you build UI:

Button/Primary, Button/SecondaryCard/Product, Card/ArticleForm/Input/Text, Form/CheckboxAvoid leaving everything as “Rectangle 12” or “Group 5”—that pushes the AI toward generic wrappers instead of reusable components.

Manual positioning often turns into absolute coordinates in code. If you want flex/grid output, your design should behave like flex/grid:

When the design responds well inside the design tool, the generated UI is much more likely to be responsive by default.

One-off colors, font sizes, and spacing values encourage one-off CSS. Instead:

This improves consistency and makes it easier to refactor toward a design system later.

AI can’t infer what it can’t find. Add key variants like hover/pressed/disabled, error states for inputs, loading states, and empty states.

When behavior matters, annotate it briefly: “opens modal”, “server-validated”, “shows toast on success”. A single line near a component can prevent incorrect interaction code.

If you’re standardizing a team workflow, capture these conventions in a lightweight checklist and link it internally (e.g., /blog/design-to-code-checklist).

AI-generated UI code is best treated like a first draft: it can save hours, but it still needs a human pass to ensure the UI behaves correctly, stays maintainable, and matches product standards.

Start by reading the markup as if you were a screen reader.

<h1>, then logical <h2>/<h3>).<ul>/<ol>) and not stacked <div>s.If semantics are wrong, fixing CSS won’t rescue accessibility or usability.

Many generators rely on absolute positioning or deeply nested wrappers to “match the screenshot.” That tends to break when content changes.

Prefer flex/grid rules over coordinates, and reduce nesting until each wrapper has a clear reason to exist (layout grouping, spacing, or component boundary). If you see repeated style={{ left, top, width, height }} patterns, rewrite that area first.

Look for repeating UI patterns (cards, input rows, nav items) and turn them into reusable components. Then replace hard-coded values with tokens: spacing, radius, typography, and colors. If your team already has token guidance, align to it; otherwise, start with a minimal set and expand deliberately (see /blog/design-tokens).

You don’t need a heavy test suite to get value.

Generators guess intent. Capture any edits you made (interaction rules, breakpoints, component mapping decisions) so the next generation pass—or the next developer—doesn’t undo them.

AI “design to code” works best when you treat it as an accelerator, not an autopilot. The fastest teams pick a workflow that matches the maturity of their design system and the risk level of the screen they’re building.

1) AI assist inside design tools (e.g., Figma plugins): Great for staying close to the source file. You get quick scaffolding while designers iterate, and it’s easier to keep names, components, and tokens aligned with the file.

2) External converters (upload/export → code): Useful when you need a repeatable pipeline across many files or teams. It can be faster for bulk conversion, but you often spend more time cleaning up structure and wiring interactions.

In practice, many teams end up combining design-to-code with a broader “spec to shipped app” flow. For example, platforms like Koder.ai take the same principle—turning intent into implementation—and extend it beyond UI scaffolding: you can describe features in chat, generate React frontends with Go/PostgreSQL backends (and Flutter for mobile), then iterate with planning mode, snapshots, rollback, and source-code export when it’s time to integrate with an existing repo.

AI shines on:

Be cautious with:

Treat each generation as a draft: review output, note recurring issues (naming, missing states, incorrect semantics), then update your prompt/spec and design conventions. Over a few rounds, quality improves more than you’d expect.

Before committing, run a small pilot and score results on: fidelity to layout, component reuse, responsiveness, accessibility basics, and refactor time. If you’re comparing tooling options and plans, check /pricing.

It’s an AI-assisted translation from a visual UI (Figma frame, design export, or screenshot) into runnable UI code. The goal is a solid first draft—layout, styling rhythm, and basic structure—so a developer can refactor into tokens, components, and production-quality semantics.

It typically translates:

Pixels don’t encode everything. You usually must specify or provide:

A screenshot is the thinnest input: it has color and geometry but no explicit structure (layers, constraints, components). Expect more guesswork, more absolute positioning, and less reusable code.

A Figma/Sketch file or structured export provides frames, layer names, Auto Layout, constraints, and styles—signals that help produce cleaner flex/grid layouts and more accurate component boundaries.

AI looks for repeated alignment and consistent gaps to express the UI as flex/grid rules. If it finds a clear spacing rhythm (like 8/16/24), it can generate stable stacks and grids.

If spacing is inconsistent or elements are slightly misaligned, the model often falls back to absolute coordinates to preserve the exact look—at the cost of responsiveness.

It searches for visual “enclosure” signals:

Clean grouping and consistent structure in the design tool (frames, Auto Layout) makes parent/child relationships much easier to reproduce in code.

Absolute positioning appears when relationships are ambiguous—overlaps, inconsistent spacing, manual nudges, or unclear grouping. It can match one screen size but tends to break with:

If you want flexible output, make the design behave like flex/grid via Auto Layout and constraints.

It infers hierarchy from visual cues:

When styles differ by only 1–2px or hierarchy steps are unclear, it may choose the wrong heading level or treat headings as plain text.

AI guesses interactivity from UI affordances:

If a “card” could be clickable or informational, annotate or show a variant; otherwise the model may wire the wrong behavior or omit it entirely.

Do a fast, structured pass:

Treat the output as scaffolding, then document assumptions so future generations don’t undo your decisions.