Jul 13, 2025·8 min

How Backend Frameworks Shape Code Organization & Team Habits

Learn how backend frameworks influence folder structure, boundaries, testing, and team workflows—so teams can ship faster with consistent, maintainable code.

Learn how backend frameworks influence folder structure, boundaries, testing, and team workflows—so teams can ship faster with consistent, maintainable code.

A backend framework is more than a bundle of libraries. Libraries help you do specific jobs (routing, validation, ORM, logging). A framework adds an opinionated “way of working”: a default project structure, common patterns, built-in tooling, and rules about how pieces connect.

Once a framework is in place, it guides hundreds of small choices:

This is why two teams building “the same API” can end up with very different codebases—even if they use the same language and database. The framework’s conventions become the default answer to “how do we do this here?”

Frameworks often trade flexibility for predictable structure. The upside is faster onboarding, fewer debates, and reusable patterns that reduce accidental complexity. The downside is that framework conventions can feel restrictive when your product needs unusual workflows, performance tuning, or non-standard architectures.

A good decision isn’t “framework or not,” but how much convention you want—and whether your team is willing to keep paying the cost of customization over time.

Most teams don’t start with an empty folder—they start with a framework’s “recommended” layout. Those defaults decide where people put code, how they name things, and what feels “normal” in reviews.

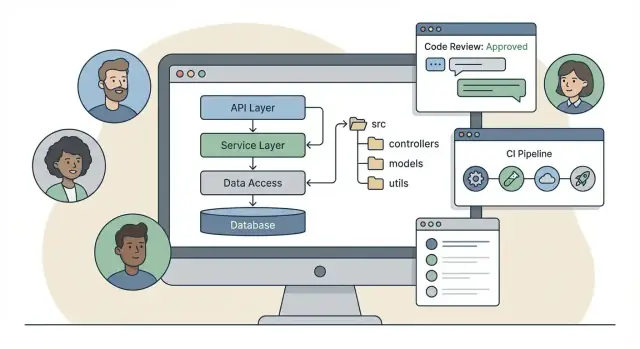

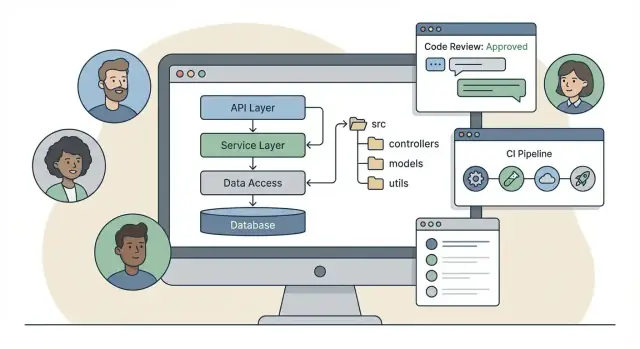

Some frameworks push a classic layered structure: controllers / services / models. It’s easy to learn and maps neatly to request handling:

/src

/controllers

/services

/models

/repositories

Other frameworks lean toward feature modules: group everything for one feature together (HTTP handlers, domain rules, persistence). That encourages local reasoning—when you work on “Billing,” you open one folder:

/src

/modules

/billing

/http

/domain

/data

Neither is automatically better, but each shapes habits. Layered structures can make cross-cutting standards (logging, validation, error handling) easier to centralize. Module-first structures can reduce “horizontal scrolling” across the codebase as it grows.

CLI generators (scaffolding) are sticky. If the generator creates a controller + service pair for every endpoint, people will keep doing that—even when a simpler function would do. If it generates a module with clear boundaries, teams are more likely to respect those boundaries under deadline pressure.

This same dynamic shows up in “vibe-coding” workflows too: if your platform’s defaults produce a predictable layout and clear module seams, teams tend to keep the codebase coherent as it grows. For example, Koder.ai generates full-stack apps from chat prompts, and the practical benefit (beyond speed) is that your team can standardize on consistent structures and patterns early—then iterate on them like any other codebase (including exporting the source code when you want full control).

Frameworks that make controllers the star can tempt teams to cram business rules into request handlers. A useful rule of thumb: controllers translate HTTP → application call, and nothing more. Put business logic in a service/use-case layer (or module domain layer), so it can be tested without HTTP and reused by background jobs or CLI tasks.

If you can’t answer “Where does pricing logic live?” in one sentence, your framework defaults might be fighting your domain. Adjust early—folders are easy to change; habits are not.

A backend framework isn’t just a set of libraries—it defines how a request should travel through your code. When everyone follows the same request path, features ship faster and reviews become less about style and more about correctness.

Routes should read like a table of contents for your API. Good frameworks encourage routes that are:

A practical convention is to keep route files focused on mapping: GET /orders/:id -> OrdersController.getById, not “if user is VIP, do X.”

Controllers (or handlers) work best as translators between HTTP and your core logic:

When frameworks provide helpers for parsing, validation, and response formatting, teams are tempted to pile logic into controllers. The healthier pattern is “thin controllers, thick services”: keep request/response concerns in controllers, and keep business decisions in a separate layer that doesn’t know about HTTP.

Middleware (or filters/interceptors) shapes where teams put repeated behaviors like authentication, logging, rate limiting, and request IDs. The key convention: middleware should enrich or guard the request, not implement product rules.

For example, auth middleware can attach req.user, and controllers can pass that identity into core logic. Logging middleware can standardize what gets logged without every controller reinventing it.

Agree on predictable names:

OrdersController, OrdersService, CreateOrder (use-case)authMiddleware, requestIdMiddlewarevalidateCreateOrder (schema/validator)When names encode intent, code reviews focus on behavior, not where things “should have gone.”

A backend framework doesn’t just help you ship endpoints—it pushes your team toward a particular “shape” of code. If you don’t define boundaries early, the default gravity is often: controllers call the ORM, the ORM calls the database, and business rules get sprinkled everywhere.

A simple, durable split looks like this:

CreateInvoice, CancelSubscription). Orchestrates work and transactions, but stays framework-lean.Frameworks that generate “controllers + services + repositories” can be helpful—if you treat it as directional flow, not as a requirement that every feature needs every layer.

An ORM makes it tempting to pass database models everywhere because they’re convenient and already validated-ish. Repositories help by giving you a narrower interface (“get customer by id”, “save invoice”), so your application and domain code don’t depend on ORM details.

To avoid “everything depends on the database” designs:

Add a service/application use-case layer when logic is reused across endpoints, requires transactions, or must enforce rules consistently. Skip it for simple CRUD that truly has no business behavior—adding layers there can create ceremony without clarity.

Dependency Injection (DI) is one of those framework defaults that trains your whole team. When it’s baked into the framework, you stop “new-ing up” services in random places and start treating dependencies as something you declare, wire, and swap intentionally.

DI nudges teams toward small, focused components: a controller depends on a service, a service depends on a repository, and each part has a clear role. That tends to improve testability and makes it easier to replace implementations (for example, a real payment gateway vs. a mock).

The downside is that DI can hide complexity. If every class depends on five other classes, it becomes harder to understand what actually runs on a request. Misconfigured containers can also cause errors that feel far away from the code you were editing.

Most frameworks push constructor injection because it makes dependencies explicit and prevents “service locator” patterns.

A helpful habit is pairing constructor injection with interface-driven design: code depends on a stable contract (like EmailSender) rather than a specific vendor client. That keeps changes localized when you switch providers or refactor.

DI works best when your modules are cohesive: one module owns one slice of functionality (orders, billing, auth) and exposes a small public surface.

Circular dependencies are a common failure mode. They’re often a sign that boundaries are unclear—two modules share concepts that deserve their own module, or one module is doing too much.

Teams should agree on where dependencies are registered: a single composition root (startup/bootstrap), plus module-level wiring for module internals.

Keeping wiring centralized makes code reviews easier: reviewers can spot new dependencies, confirm they’re justified, and prevent “container sprawl” that turns DI from a tool into a mystery.

A backend framework influences what “a good API” looks like on your team. If validation is a first-class feature (decorators, schemas, pipes, request guards), people design endpoints around clear inputs and predictable outputs—because it’s easier to do the right thing than to skip it.

When validation lives at the boundary (before business logic), teams start treating request payloads as contracts, not “whatever the client sends.” That usually leads to:

This is also where frameworks encourage shared conventions: where validation is defined, how errors are surfaced, and whether unknown fields are allowed.

Frameworks that support global exception filters/handlers make consistency achievable. Instead of each controller inventing its own responses, you can standardize:

code, message, details, traceId)A consistent error shape reduces front-end branching logic and makes API docs easier to trust.

Many frameworks nudge you toward DTOs (input) and view models (output). That separation is healthy: it prevents accidental exposure of internal fields, avoids coupling clients to database schemas, and makes refactors safer. A practical rule: controllers speak in DTOs; services speak in domain models.

Even small APIs evolve. Framework routing conventions often determine whether versioning is URL-based (/v1/...) or header-based. Whichever you pick, set the basics early: never remove fields without a deprecation window, add fields in a backward-compatible way, and document changes in one place (e.g., /docs or /changelog).

A backend framework doesn’t just help you ship features; it dictates how you test them. The built-in test runner, bootstrapping utilities, and DI container often determine what’s easy—which becomes what your team actually does.

Many frameworks provide a “test app” bootstrapper that can spin up the container, register routes, and run requests in-memory. That nudges teams toward integration tests early—because they’re only a few lines more than a unit test.

A practical split looks like this:

For most services, speed matters more than perfect “pyramid” purity. A good rule is: keep lots of small unit tests, a focused set of integration tests around boundaries (database, queues), and a thin E2E layer that proves the contract.

If your framework makes request simulation cheap, you can lean slightly heavier on integration tests—while still isolating domain logic so unit tests remain stable.

Mocking strategy should follow how your framework resolves dependencies:

Framework boot time can dominate CI. Keep tests snappy by caching expensive setup, running DB migrations once per suite, and using parallelization only where isolation is guaranteed. Make failures easy to diagnose: consistent seeding, deterministic clocks, and strict cleanup hooks beat “retry on fail.”

Frameworks don’t just help you ship the first API—they shape how your code grows when the “one service” turns into dozens of features, teams, and integrations. The module and package mechanics your framework makes easy will usually become your long-term architecture.

Most backend frameworks nudge you toward modularity by design: apps, plugins, blueprints, modules, feature folders, or packages. When that’s the default, teams tend to add new capabilities as “one more module” rather than sprinkling new files across the whole project.

A practical rule: treat each module as a mini-product with its own public surface (routes/handlers, service interfaces), private internals, and tests. If your framework supports auto-discovery (e.g., module scanning), use it carefully—explicit imports often make dependencies easier to reason about.

As the codebase grows, mixing business rules with adapters becomes expensive. A useful split is:

Framework conventions influence this: if the framework encourages “service classes,” place domain services in core modules and keep framework-specific wiring (controllers, middleware, providers) at the edges.

Teams often over-share too early. Prefer copying small code until it’s stable, then extract when:

If you do extract, publish internal packages (or workspace libraries) with strict ownership and changelog discipline.

A modular monolith is often the best “middle scale.” If modules have clear boundaries and minimal cross-imports, you can later lift a module into a service with less churn. Design modules around business capabilities, not technical layers. For a deeper strategy, see /blog/modular-monolith.

A framework’s configuration model shapes how consistent (or chaotic) your deployments feel. When config is scattered across ad-hoc files, random environment variables, and “just this one constant,” teams end up debugging differences instead of building features.

Most frameworks nudge you toward a primary source of truth: configuration files, environment variables, or code-based configuration (modules/plugins). Whichever path you choose, standardize it early:

config/default.yml).A good convention is: defaults live in versioned config files, environment variables override per environment, and code reads from one typed config object. That keeps “where to change a value” obvious during incidents.

Frameworks often provide helpers for reading env vars, integrating secret stores, or validating config at startup. Use that tooling to make secrets hard to mishandle:

.env sprawl.The operational habit you’re aiming for is simple: developers can run locally with safe placeholders, while real credentials only exist in the environment that needs them.

Framework defaults can either encourage parity (same boot process everywhere) or create special cases (“production uses a different server entrypoint”). Aim for the same startup command and the same config schema across environments, changing only values.

Staging should be treated as a rehearsal: same feature flags, same migrations path, same background jobs—just smaller scale.

When configuration isn’t documented, teammates guess—and guesses become outages. Keep a short, maintained reference in the repo (for example, /docs/configuration) listing:

Many frameworks can validate config on boot. Pair that with documentation and you reduce “works on my machine” to a rare exception instead of a recurring theme.

A backend framework sets the baseline for how you understand your system in production. When observability is built in (or strongly encouraged), teams stop treating logs and metrics as “later” work and start designing them as part of the API.

Many frameworks integrate directly with common tooling for structured logging, distributed tracing, and metrics collection. That integration influences code organization: you tend to centralize cross-cutting concerns (logging middleware, tracing interceptors, metrics collectors) instead of sprinkling print statements across controllers.

A good standard is to define a small set of required log fields that every request-related log line includes:

correlation_id (or request_id) to connect logs across servicesroute and method to understand which endpoint is involveduser_id or account_id (when available) for support investigationsduration_ms and status_code for performance and reliabilityFramework conventions (like request context objects or middleware pipelines) make it easier to generate and pass correlation IDs consistently, so developers don’t reinvent the pattern per feature.

Framework defaults often determine whether health checks are first-class citizens or an afterthought. Standard endpoints like /health (liveness) and /ready (readiness) become part of the team’s definition of “done,” and they push you toward cleaner boundaries:

When these endpoints are standardized early, operational requirements stop leaking into random feature code.

Observability data is also a decision-making tool. If traces show that a single endpoint repeatedly spends time in the same dependency, that’s a clear signal to extract a module, add caching, or redesign a query. If logs reveal inconsistent error shapes, it’s a prompt to centralize error handling. In other words: the framework’s observability hooks don’t just help you debug—they help you reorganize the codebase with confidence.

A backend framework doesn’t just organize code—it sets the “house rules” for how a team works. When everyone follows the same conventions (file placement, naming, how dependencies are wired), reviews get faster and onboarding gets easier.

Scaffolding tools can standardize new endpoints, modules, and tests in minutes. The trap is letting generators dictate your domain model.

Use scaffolds to create consistent shells (routes/controllers, DTOs, test stubs), then immediately edit the output to match your architecture rules. A good policy is: generators are allowed, but the final code must still read like a thoughtful design—not a template dump.

If you’re using an AI-assisted workflow, apply the same discipline: treat generated code as scaffolding. On platforms like Koder.ai, you can iterate quickly via chat while still enforcing your team conventions (module boundaries, DI patterns, error shapes) through reviews—because speed only helps if the structure stays predictable.

Frameworks often imply an idiomatic structure: where validation lives, how errors are raised, how services are named. Capture those expectations in a short team style guide that includes:

Keep it lightweight and actionable; link to it from /contributing.

Make standards automatic. Configure formatters and linters to reflect framework conventions (imports, decorators/annotations, async patterns). Then enforce them consistently via pre-commit hooks and CI, so reviews focus on design instead of whitespace and naming.

A framework-based checklist prevents slow drift into inconsistency. Add a PR template that asks reviewers to confirm things like:

Over time, these small workflow guardrails are what keep a codebase maintainable as the team grows.

Framework choices tend to lock in patterns—directory layout, controller style, dependency injection, and even how people write tests. The goal isn’t to pick the perfect framework; it’s to pick one that matches how your team ships software, and to keep change possible when requirements shift.

Start with your delivery constraints, not feature checklists. A small team usually benefits from strong conventions, batteries-included tooling, and fast onboarding. Larger teams often need clearer module boundaries, stable extension points, and patterns that make it hard to create hidden coupling.

Ask practical questions:

A rewrite is often the end result of smaller pains ignored for too long. Watch for:

You can evolve without stopping feature work by introducing seams:

Before committing (or before the next major upgrade), do a short trial:

If you want a structured way to evaluate options, create a lightweight RFC and store it with the codebase (e.g., /docs/decisions) so future teams understand why you chose what you chose—and how to change it safely.

One extra lens to consider: if your team is experimenting with faster build loops (including chat-driven development), evaluate whether your workflow still produces the same architectural artifacts—clear modules, enforceable contracts, and operable defaults. The best speedups (whether from a framework CLI or a platform like Koder.ai) are the ones that reduce cycle time without eroding the conventions that keep a backend maintainable.

A backend framework provides an opinionated way to build an application: default project structure, request lifecycle conventions (routing → middleware → controllers/handlers), built-in tooling, and “blessed” patterns. Libraries usually solve isolated problems (routing, validation, ORM), but don’t enforce how those pieces fit together across a team.

Framework conventions become the default answer to everyday questions: where code lives, how requests flow, how errors are shaped, and how dependencies are wired. That consistency speeds onboarding and reduces review debates, but it also creates “lock-in” to certain patterns that can be costly to bend later.

Pick layered when you want clear separation of technical concerns and easy centralization of cross-cutting behavior (auth, validation, logging).

Pick feature modules when you want teams to work “locally” within a business capability (e.g., Billing) with minimal jumping across folders.

Whichever you choose, document the rules and enforce them in reviews so the structure stays coherent as the codebase grows.

Use generators to create consistent shells (routes/controllers, DTOs, test stubs), then treat the output as a starting point—not the architecture.

If scaffolding always produces controller+service+repo for everything, it can add ceremony to simple endpoints. Periodically review generated patterns and update templates to match how you actually want to build features.

Keep controllers focused on HTTP translation:

Move business rules into an application/service or domain layer so they’re reusable (jobs/CLI) and testable without booting the web stack.

Middleware should enrich or guard the request, not implement product rules.

Good fits:

Business decisions (pricing, eligibility, workflow branching) should live in services/use-cases where they can be tested and reused.

It improves testability and makes replacements easier (e.g., swapping a payment provider or using fakes in tests) by wiring dependencies explicitly.

Keep DI understandable by:

If you see circular dependencies, it’s usually a boundary problem—not a “DI problem.”

Treat requests/responses as contracts:

code, message, details, traceId)Use DTOs/view models so you don’t accidentally expose internal/ORM fields and so clients aren’t coupled to your database schema.

Let framework tooling guide what’s easy, but keep a deliberate split:

Prefer overriding DI bindings or using in-memory adapters over brittle monkey-patching, and keep CI fast by minimizing repeated framework boot and DB setup.

Watch for early signals:

Reduce rewrite risk by creating seams: