Sep 21, 2025·8 min

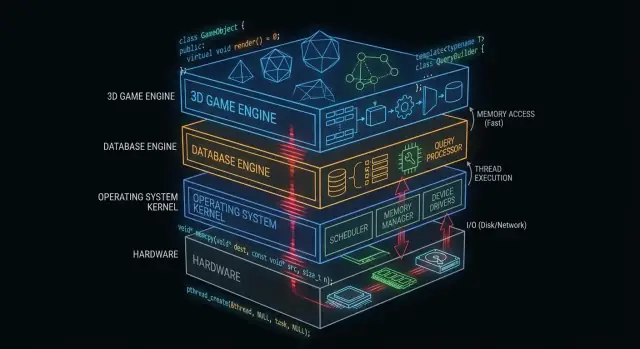

How C and C++ Still Power OS, Databases, and Game Engines

See how C and C++ still form the core of operating systems, databases, and game engines—through memory control, speed, and low-level access.

Why C and C++ Still Matter Behind the Scenes

“Under the hood” is everything your app depends on but rarely touches directly: operating system kernels, device drivers, database storage engines, networking stacks, runtimes, and performance-critical libraries.

By contrast, what many application developers see day to day is the surface area: frameworks, APIs, managed runtimes, package managers, and cloud services. Those layers are built to be safe and productive—even when they intentionally hide complexity.

Why some layers must stay close to hardware

Some software components have requirements that are hard to meet without direct control:

- Predictable performance and latency (e.g., scheduling CPU time, handling interrupts, streaming assets)

- Precise memory control (layout, alignment, cache behavior, avoiding pauses)

- Direct hardware access (registers, DMA, drivers, filesystems and block devices)

- Small, portable binaries that can run early in boot or in constrained environments

C and C++ are still common here because they compile to native code with minimal runtime overhead and give engineers fine-grained control over memory and system calls.

Where C and C++ are most common today

At a high level, you’ll find C and C++ powering:

- Operating system cores and low-level libraries

- Drivers and embedded firmware

- Database engines (query execution, storage, indexing)

- Game engines and real-time subsystems (rendering, physics, audio)

- Compilers, toolchains, and language runtimes that other languages rely on

What this post will (and won’t) cover

This article focuses on the mechanics: what these “behind the scenes” components do, why they benefit from native code, and what trade-offs come with that power.

It won’t claim C/C++ are the best choice for every project, and it won’t turn into a language war. The goal is practical understanding of where these languages still earn their keep—and why modern software stacks continue to build on them.

What Makes C and C++ a Fit for Systems Software

C and C++ are widely used for systems software because they enable “close to the metal” programs: small, fast, and tightly integrated with the OS and hardware.

Compiled to native code (plain English)

When C/C++ code is compiled, it becomes machine instructions that the CPU can execute directly. There’s no required runtime translating instructions while the program runs.

That matters for infrastructure components—kernels, database engines, game engines—where even small overheads can compound under load.

Predictable performance for core infrastructure

Systems software often needs consistent timing, not just good average speed. For example:

- An operating system scheduler must respond quickly under load.

- A database must keep latency stable while many users query at once.

- A game engine must hit a frame budget (for example, ~16 ms for 60 FPS).

C/C++ provide control over CPU usage, memory layout, and data structures, which helps engineers target predictable performance.

Direct memory and pointer access

Pointers let you work with memory addresses directly. That power can sound intimidating, but it unlocks capabilities that many higher-level languages abstract away:

- Custom allocators tuned to specific workloads

- Compact in-memory formats (useful in databases and caches)

- Zero-copy I/O patterns where data isn’t repeatedly duplicated

Used carefully, this level of control can deliver dramatic efficiency gains.

Trade-offs: safety, complexity, and development time

The same freedom is also the risk. Common trade-offs include:

- Safety: mistakes can cause crashes, data corruption, or security vulnerabilities.

- Complexity: manual memory management and undefined behavior require discipline.

- Development time: testing, review, and tooling become non-negotiable for reliability.

A common approach is to keep the performance-critical core in C/C++, then surround it with safer languages for product features and UX.

C/C++ in Operating System Kernels

The operating system kernel sits closest to the hardware. When your laptop wakes up, your browser opens, or a program asks for more RAM, the kernel is coordinating those requests and deciding what happens next.

What a kernel actually does

At a practical level, kernels handle a few core jobs:

- Scheduling: deciding which program (and which thread) gets CPU time, and for how long.

- Memory management: handing out memory to processes, keeping them isolated, and reclaiming memory safely.

- Device management: talking to hardware through drivers (disk, network, keyboard, GPU, etc.).

- Security boundaries: enforcing permissions so one program can’t read or corrupt another program’s data.

Because these responsibilities sit at the center of the system, kernel code is both performance-sensitive and correctness-sensitive.

Why tight control favors C (and sometimes C++)

Kernel developers need precise control over:

- Memory layout: fixed-size structures, alignment, and predictable allocation behavior.

- CPU instructions and calling conventions: interacting with interrupts, context switches, and low-level synchronization.

- Hardware registers: reading/writing specific addresses and handling special CPU modes.

C remains a common “kernel language” because it maps cleanly to machine-level concepts while staying readable and portable across architectures. Many kernels also rely on assembly for the smallest, most hardware-specific parts, with C doing the bulk of the work.

C++ can appear in kernels, but usually in a restricted style (limited runtime features, careful exception policies, and strict rules about allocation). Where it’s used, it’s typically to improve abstraction without giving up control.

Kernel-adjacent code often written in C/C++

Even when the kernel itself is conservative, many nearby components are C/C++:

- Device drivers (especially performance-critical ones)

- Standard libraries and runtimes (parts of libc, low-level threading)

- Bootloaders and early startup code

- System services that need native speed (e.g., networking or storage helpers)

For more on how drivers bridge software and hardware, see /blog/device-drivers-and-hardware-access.

Device Drivers and Hardware Access

Device drivers translate between an operating system and physical hardware—network cards, GPUs, SSD controllers, audio devices, and more. When you click “play,” copy a file, or connect to Wi‑Fi, a driver is often the first code that must respond.

Because drivers sit on the hot path for I/O, they’re extremely performance-sensitive. A few extra microseconds per packet or per disk request can add up quickly on busy systems. C and C++ remain common here because they can call OS kernel APIs directly, control memory layout precisely, and run with minimal overhead.

Interrupts, DMA, and why low-level APIs matter

Hardware doesn’t politely “wait its turn.” Devices signal the CPU via interrupts—urgent notifications that something happened (a packet arrived, a transfer finished). Driver code must handle these events quickly and correctly, often under tight timing and threading constraints.

For high throughput, drivers also rely on DMA (Direct Memory Access), where devices read/write system memory without the CPU copying every byte. Setting up DMA typically involves:

- Preparing buffers in the right format and alignment

- Handing the device physical addresses or mapped descriptors

- Synchronizing ownership of memory between device and CPU

These tasks require low-level interfaces: memory-mapped registers, bit flags, and careful ordering of reads/writes. C/C++ make it practical to express this kind of “close to the metal” logic while still being portable across compilers and platforms.

Stability is non-negotiable

Unlike a normal app, a driver bug can crash the whole system, corrupt data, or open security holes. That risk shapes how driver code is written and reviewed.

Teams reduce danger by using strict coding standards, defensive checks, and layered reviews. Common practices include limiting unsafe pointer use, validating inputs from hardware/firmware, and running static analysis in CI.

Memory Management: Power and Pitfalls

Ship the first version fast

Turn your idea into a working web app without setting up a full toolchain first.

Memory management is one of the biggest reasons C and C++ still dominate parts of operating systems, databases, and game engines. It’s also one of the easiest places to create subtle bugs.

What “memory management” means

At a practical level, memory management includes:

- Allocating memory (getting a chunk to store data)

- Freeing it (giving it back when you’re done)

- Handling fragmentation (leftover holes that make future allocations slower or harder)

In C, this is often explicit (malloc/free). In C++, it may be explicit (new/delete) or wrapped in safer patterns.

Why manual control can be an advantage

In performance-critical components, manual control can be a feature:

- You can avoid unpredictable pauses from garbage collection.

- You can choose where and how memory is allocated (e.g., pooled or arena allocators), improving consistency.

- You can tailor allocation patterns to real workloads (many small objects vs. large contiguous buffers).

This matters when a database must maintain steady latency or a game engine must hit a frame-time budget.

Common failure modes (and why they’re serious)

The same freedom creates classic problems:

- Memory leaks: forgetting to free memory, causing usage to grow until performance degrades or the process crashes.

- Buffer overflows: writing past the end of an array, corrupting data or enabling exploits.

- Use-after-free: using a pointer after freeing it, leading to crashes that are difficult to reproduce.

These bugs can be subtle because the program may “seem fine” until a specific workload triggers failure.

How modern practices help

Modern C++ reduces risk without giving up control:

- RAII (Resource Acquisition Is Initialization) ties resource lifetime to scope so cleanup happens automatically.

- Smart pointers (like

std::unique_ptrandstd::shared_ptr) make ownership explicit and prevent many leaks. - Sanitizers (AddressSanitizer, UndefinedBehaviorSanitizer) and static analysis catch issues early, often in CI.

Used well, these tools keep C/C++ fast while making memory bugs less likely to reach production.

Concurrency and Multi-Core Performance

Modern CPUs aren’t getting dramatically faster per core—they’re getting more cores. That shifts the performance question from “How fast is my code?” to “How well can my code run in parallel without tripping over itself?” C and C++ are popular here because they allow low-level control over threading, synchronization, and memory behavior with very little overhead.

Threads, cores, and scheduling

A thread is the unit your program uses to do work; a CPU core is where that work runs. The operating system scheduler maps runnable threads onto available cores, constantly making trade-offs.

Small scheduling details matter in performance-critical code: pausing a thread at the wrong moment can stall a pipeline, create queue backlogs, or produce stop-and-go behavior. For CPU-bound work, keeping active threads roughly aligned with core count often reduces thrashing.

Locking basics: mutexes, atomics, and contention

- Mutexes are easy to reason about, but heavy sharing creates contention—time spent waiting instead of working.

- Atomics can be faster for small shared-state updates, but require careful design to avoid subtle correctness bugs.

The practical goal isn’t “never lock.” It’s: lock less, lock smarter—keep critical sections small, avoid global locks, and reduce shared mutable state.

Why latency spikes matter

Databases and game engines don’t just care about average speed—they care about worst-case pauses. A lock convoy, page fault, or stalled worker can cause visible stutter or a slow query that violates an SLA.

Common C/C++ patterns

Many high-performance systems rely on:

- Thread pools to reuse workers and keep scheduling predictable.

- Work-stealing queues to balance load across cores.

- Lock-free queues (in select hot paths) to reduce blocking—used carefully because correctness is harder to prove.

These patterns aim for steady throughput and consistent latency under pressure.

Database Engines: Where C/C++ Delivers Speed

A database engine isn’t just “storing rows.” It’s a tight loop of CPU and I/O work that runs millions of times per second, where small inefficiencies add up fast. That’s why so many engines and core components are still written largely in C or C++.

The engine’s main job: parse, plan, execute

When you send SQL, the engine:

- Parses it (turning text into a structured representation)

- Plans it (choosing an efficient way to answer the query)

- Executes it (scans, index lookups, joins, sorts, aggregates, and returns rows)

Each stage benefits from careful control over memory and CPU time. C/C++ enables fast parsers, fewer allocations during planning, and a lean execution hot path—often with custom data structures designed for the workload.

Storage engines: pages, indexes, buffering

Under the SQL layer, the storage engine handles the unglamorous but essential details:

- Pages: data is read and written in fixed-size blocks, not row-by-row.

- Indexes: B-trees, LSM-trees, and related structures must be updated efficiently.

- Buffering: a buffer pool decides what stays in memory, what gets evicted, and how reads/writes are batched.

C/C++ is a strong fit here because these components rely on predictable memory layout and direct control over I/O boundaries.

Cache-friendly data structures (why it matters)

Modern performance often depends more on CPU caches than raw CPU speed. With C/C++, developers can pack frequently used fields together, store columns in contiguous arrays, and minimize pointer chasing—patterns that keep data close to the CPU and reduce stalls.

Where higher-level languages still show up

Even in C/C++-heavy databases, higher-level languages often power admin tools, backups, monitoring, migrations, and orchestration. The performance-critical core stays native; the surrounding ecosystem prioritizes iteration speed and usability.

Storage, Caching, and I/O in Databases

Keep native code isolated

Prototype an FFI boundary and connect your app to existing C or C++ code.

Databases feel instant because they work hard to avoid disk. Even on fast SSDs, reading from storage is orders of magnitude slower than reading from RAM. A database engine written in C or C++ can control every step of that wait—and often avoid it.

Buffer pool and page cache in everyday terms

Think of data on disk as boxes in a warehouse. Fetching a box (disk read) takes time, so you keep the most-used items on a desk (RAM).

- Buffer pool: the database’s own “desk,” holding recently used pages (fixed-size chunks of tables and indexes).

- Page cache: the operating system’s “desk,” caching recently read file data.

Many databases manage their own buffer pool to predict what should stay hot and avoid fighting with the OS over memory.

Why disk is slow—and how caching hides it

Storage isn’t just slow; it’s also unpredictable. Latency spikes, queueing, and random access all add delays. Caching mitigates this by:

- Serving reads from RAM most of the time

- Batching writes into fewer, larger I/O operations

- Prefetching pages likely to be needed next (e.g., during index scans)

Design choices that benefit from low-level control

C/C++ lets database engines tune details that matter at high throughput: aligned reads, direct I/O vs. buffered I/O, custom eviction policies, and carefully structured in-memory layouts for indexes and log buffers. These choices can reduce copies, avoid contention, and keep CPU caches fed with useful data.

Compression and checksums can be CPU-bound

Caching reduces I/O, but increases CPU work. Decompressing pages, computing checksums, encrypting logs, and validating records can become bottlenecks. Because C and C++ offer control over memory access patterns and SIMD-friendly loops, they’re often used to squeeze more work out of each core.

Game Engines: Real-Time Constraints

Game engines operate under strict real-time expectations: the player moves the camera, presses a button, and the world must respond immediately. This is measured in frame time, not average throughput.

Frame budgets: why milliseconds matter

At 60 FPS, you get about 16.7 ms to produce a frame: simulation, animation, physics, audio mixing, culling, rendering submission, and often streaming assets. At 120 FPS, that budget drops to 8.3 ms. Miss the budget and players perceive it as stutter, input lag, or inconsistent pacing.

This is why C programming and C++ programming remain common in engine cores: predictable performance, low overhead, and fine control over memory and CPU usage.

Core subsystems often written in C/C++

Most engines use native code for the heavy lifting:

- Rendering (scene traversal, draw-call building, GPU resource management)

- Physics (collision detection, constraints, rigid bodies)

- Animation (skeletal blending, IK, pose evaluation)

- Audio (real-time mixing, spatialization)

These systems run every frame, so small inefficiencies multiply quickly.

Tight loops and data layout

A lot of game performance comes down to tight loops: iterating entities, updating transforms, testing collisions, skinning vertices. C/C++ makes it easier to structure memory for cache efficiency (contiguous arrays, fewer allocations, fewer virtual indirections). Data layout can matter as much as algorithm choice.

Where scripting fits (and where it doesn’t)

Many studios use scripting languages for gameplay logic—quests, UI rules, triggers—because iteration speed matters. The engine core typically remains native, and scripts call into C/C++ systems through bindings. A common pattern: scripts orchestrate; C/C++ executes the expensive parts.

Compilers, Toolchains, and Interop

Practice performance thinking

Build an internal dashboard to explore performance and latency basics with real endpoints.

C and C++ don’t just “run”—they’re built into native binaries that match a specific CPU and operating system. That build pipeline is a major reason these languages remain central to operating systems, databases, and game engines.

What actually happens during a build

A typical build has a few stages:

- Compiler: turns C/C++ source into machine-specific object files.

- Linker: stitches objects together with libraries to produce an executable or shared library.

- Binary output: the final artifact the OS can load directly (often with separate debug symbols).

The linker step is where many real-world issues surface: missing symbols, mismatched library versions, or incompatible build settings.

Why toolchains and platform support matter

A toolchain is the full set: compiler, linker, standard library, and build tools. For systems software, platform coverage is often decisive:

- Console and mobile SDKs may require specific compilers and linkers.

- Databases and backend software need stable builds across Linux distributions and CPU types.

- OS and driver work can require cross-compilers, strict flags, and ABI discipline.

Teams often choose C/C++ partly because toolchains are mature and available across environments—from embedded devices to servers.

Interfacing with other languages (FFI)

C is commonly treated as the “universal adapter.” Many languages can call C functions via FFI, so teams often put performance-critical logic in a C/C++ library and expose a small API to higher-level code. That’s why Python, Rust, Java, and others frequently wrap existing C/C++ components rather than rewriting them.

Debugging and profiling: what teams measure

C/C++ teams typically measure:

- CPU time (hot functions, call stacks)

- Memory use (allocations, leaks, fragmentation)

- Latency (frame time in games, query time in databases)

- I/O behavior (cache misses, disk reads, syscalls)

The workflow is consistent: find the bottleneck, confirm with data, then optimize the smallest piece that matters.

Choosing C/C++ Today: Practical Decision Guide

C and C++ are still excellent tools—when you’re building software where a few milliseconds, a few bytes, or a specific CPU instruction genuinely matter. They’re not the default best choice for every feature or team.

When C/C++ is the right choice

Pick C/C++ when the component is performance-critical, needs tight memory control, or must integrate closely with the OS or hardware.

Typical fits include:

- Hot paths where latency is visible (parsing, compression, rendering, query execution)

- Low-level modules that must be predictable (allocators, schedulers, networking primitives)

- Cross-platform libraries where native code is the product (SDKs, engines, embedded)

- Situations where portability across compilers/toolchains is a hard requirement

When to prefer other languages

Choose a higher-level language when the priority is safety, iteration speed, or maintainability at scale.

It’s often smarter to use Rust, Go, Java, C#, Python, or TypeScript when:

- The team is large and turnover is expected (fewer foot-guns matters)

- The feature changes frequently and correctness outweighs squeezing cycles

- You need strong memory-safety guarantees

- Developer productivity and the hiring pool are bigger constraints than raw speed

In practice, most products are a mix: native libraries for the critical path, and higher-level services and UIs for everything else.

A practical note for app teams (where Koder.ai fits)

If you’re primarily building web, backend, or mobile features, you often don’t need to write C/C++ to benefit from it—you consume it through your OS, database, runtime, and dependencies. Platforms like Koder.ai lean into that split: you can quickly produce React web apps, Go + PostgreSQL backends, or Flutter mobile apps via a chat-driven workflow, while still integrating native components when needed (for example, calling into an existing C/C++ library through an FFI boundary). This keeps most of the product surface in fast-to-iterate code, without ignoring where native code is the right tool.

Practical checklist (component by component)

Ask these questions before committing:

- Is this on the critical path? Measure first; don’t guess.

- What are the failure modes? Memory corruption in C/C++ can be catastrophic.

- What’s the interface boundary? Can you isolate native code behind a small API?

- Do you have the expertise? Review, testing, and profiling skills are non-negotiable.

- What’s the deployment target? Consoles, embedded, kernels, and drivers often favor C/C++.

- How will you test and profile it? Plan tooling and CI from day one.

Suggested next reads

- /blog/performance-profiling-basics

- /blog/memory-leaks-and-how-to-find-them

- /pricing