Jun 10, 2025·8 min

Caching Layers Cut Load—But They Add Hidden Complexity

Caching layers cut latency and backend load, but add failure modes and operational overhead. Learn common layers, risks, and ways to manage complexity.

Caching layers cut latency and backend load, but add failure modes and operational overhead. Learn common layers, risks, and ways to manage complexity.

Caching keeps a copy of data close to where it’s needed so requests can be served faster, with fewer trips to core systems. The payoff is usually a blend of speed (lower latency), cost (fewer expensive database reads or upstream calls), and stability (origin services survive traffic spikes).

When a cache can answer a request, your “origin” (app servers, databases, third-party APIs) does less. That reduction can be dramatic: fewer queries, fewer CPU cycles, fewer network hops, and fewer opportunities for timeouts.

Caching also smooths bursts—helping systems sized for average load handle peak moments without immediately scaling (or falling over).

Caching doesn’t remove work; it moves it into design and operations. You inherit new questions:

Each caching layer adds configuration, monitoring, and edge cases. A cache that makes 99% of requests faster can still cause painful incidents in the 1%: synchronized expirations, inconsistent user experiences, or sudden floods to the origin.

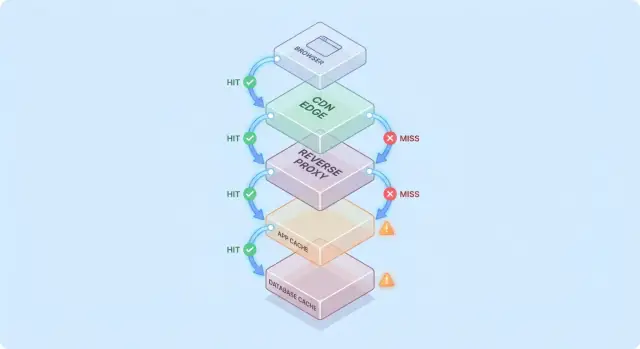

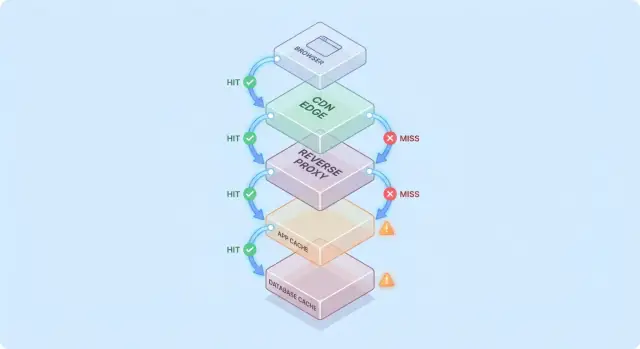

A single cache is one store (for example, an in-memory cache next to your application). A caching layer is a distinct checkpoint in the request path—CDN, browser cache, application cache, database cache—each with its own rules and failure modes.

This post focuses on the practical complexity introduced by multiple layers: correctness, invalidation, and operations (not low-level cache algorithms or vendor-specific tuning).

Caching gets easier to reason about when you picture a request traveling through a stack of “maybe I already have it” checkpoints.

A common path looks like this:

At each hop, the system can either return a cached response (hit) or forward the request to the next layer (miss). The earlier the hit happens (for example at the edge), the more load you avoid deeper in the stack.

Hits make dashboards look great. Misses are where complexity appears: they trigger real work (app logic, database queries) and add overhead (cache lookups, serialization, cache writes).

A useful mental model is: every miss pays for the cache twice—you still do the original work, plus the caching work around it.

Adding a cache layer rarely eliminates bottlenecks; it often moves them:

Suppose your product page is cached at the CDN for 5 minutes, and the app also caches product details in Redis for 30 minutes.

If a price changes, the CDN might refresh quickly while Redis continues serving the old price. Now “truth” depends on which layer answered the request—an early glimpse of why caching layers cut load but increase system complexity.

Caching isn’t one feature—it’s a stack of places where data can be saved and reused. Each layer can reduce load, but each has different rules for freshness, invalidation, and visibility.

Browsers cache images, scripts, CSS, and sometimes API responses based on HTTP headers (like Cache-Control and ETag). This can eliminate repeat downloads entirely—great for performance and for lowering CDN/origin traffic.

The catch: once a response is cached client-side, you don’t fully control revalidation timing. Some users may keep older assets longer (or clear cache unexpectedly), so versioned URLs (e.g., app.3f2c.js) are a common safety net.

A CDN caches content close to users. It shines for static files, public pages, and “mostly stable” responses like product images, documentation, or rate-limited API endpoints.

CDNs can also cache semi-static HTML when you’re careful with variation (cookies, headers, geo, device). Misconfigured variation rules are a frequent source of serving the wrong content to the wrong user.

Reverse proxies (like NGINX or Varnish) sit in front of your application and can cache whole responses. This is useful when you want centralized control, predictable eviction, and fast protection for origin servers during traffic spikes.

It’s typically less globally distributed than a CDN, but easier to tailor to your app’s routes and headers.

This cache targets objects, computed results, and expensive calls (e.g., “user profile by id” or “pricing rules for region”). It’s flexible and can be made aware of business logic.

It also introduces more decision points: key design, TTL choices, invalidation logic, and operational needs like sizing and failover.

Most databases cache pages, indexes, and query plans automatically; some support result caching. This can speed up repeated queries without changing application code.

It’s best viewed as a bonus, not a guarantee: database caches are typically the least predictable under diverse query patterns, and they don’t remove the cost of writes, locks, or contention the way upstream caches can.

Caching pays off most when it turns repeated, expensive backend operations into a cheap lookup. The trick is matching the cache to workloads where requests are similar enough—and stable enough—that reuse is high.

If your system serves far more reads than writes, caching can remove a large share of database and application work. Product pages, public profiles, help center articles, and search/filter results often get requested repeatedly with the same parameters.

Caching also helps with “expensive” work that isn’t strictly database-bound: generating PDFs, resizing images, rendering templates, or computing aggregates. Even a short-lived cache (seconds to minutes) can collapse repeated computation during busy periods.

Caching is especially effective when traffic is uneven. If a marketing email, news mention, or social post sends a burst of users to the same few URLs, a CDN or edge cache can absorb most of that surge.

This reduces load beyond “faster responses”: it can prevent autoscaling thrash, avoid database connection exhaustion, and buy time for rate limits and backpressure to work.

If your backend is far from your users—either literally (cross-region) or logically (a slow dependency)—caching can reduce both load and perceived slowness. Serving content from a CDN cache close to the user avoids repeated long-haul trips to the origin.

Internal caching helps too when the bottleneck is a high-latency store (a remote database, a third-party API, or a shared service). Cutting the number of calls reduces concurrency pressure and improves tail latency.

Caching delivers less benefit when responses are highly personalized (per-user data, sensitive account details) or when underlying data changes constantly (live dashboards, rapidly updating inventories). In those cases, hit rates are low, invalidation costs rise, and the saved backend work may be marginal.

A practical rule: caching is most valuable when many users ask for the same thing within a window where “the same thing” stays valid. If that overlap doesn’t exist, another caching layer can add complexity without cutting much load.

Caching is easy when data never changes. The moment it does, you inherit the hardest part: deciding when cached data stops being trustworthy, and how every cache layer learns that it changed.

Time-to-live (TTL) is appealing because it’s one number and no coordination. The problem is that “correct” TTL depends on how the data is used.

If you set a 5-minute TTL on a product price, some users will see an old price after it changes—potentially a legal or support problem. If you set it to 5 seconds, you may not reduce load much at all. Even worse, different fields in the same response change at different rates (inventory vs. description), so a single TTL forces a compromise.

Event-driven invalidation says: when the source of truth changes, publish an event and purge/update all affected cache keys. This can be very correct, but it creates new work:

That mapping is where “the two hard things: naming and invalidation” becomes painfully practical. If you cache /users/123 and also cache “top contributors” lists, a username change affects more than one key. If you don’t track relationships, you’ll serve mixed reality.

Cache-aside (app reads/writes DB, populates cache) is common, but invalidation is on you.

Write-through (write cache and DB together) reduces staleness risk, but adds latency and failure-handling complexity.

Write-back (write cache first, flush later) boosts speed, but makes correctness and recovery much harder.

Stale-while-revalidate serves slightly old data while refreshing in the background. It smooths spikes and protects the origin, but it’s also a product decision: you’re explicitly choosing “fast and mostly current” over “always latest.”

Caching changes what “correct” means. Without a cache, users mostly see the latest committed data (subject to normal database behavior). With caches, users might see data that’s slightly behind—or inconsistent between screens—sometimes without any obvious error.

Strong consistency aims for “read-after-write”: if a user updates their shipping address, the next page load should show the new address everywhere. This feels intuitive, but it can be expensive if every write must immediately purge or refresh multiple caches.

Eventual consistency allows brief staleness: the update will appear soon, but not instantly. Users tolerate this for low-stakes content (like view counts), but not for money, permissions, or anything that affects what they can do next.

A common pitfall is a write happening at the same time as cache repopulation:

Now the cache holds old data for its full TTL, even though the database is correct.

With multiple caching layers, different parts of the system can disagree:

Users interpret this as “the system is broken,” not “the system is eventually consistent.”

Versioning reduces ambiguity:

user:123:v7) let you move forward safely: a write bumps the version, and reads naturally shift to the new key without requiring perfectly timed deletes.The key decision isn’t “is stale data bad?” but where it’s bad.

Set explicit staleness budgets per feature (seconds/minutes/hours) and align them with user expectations. Search results can lag a minute; account balances and access control should not. This turns “cache correctness” into a product requirement you can test and monitor.

Caching often fails in ways that look like “everything was fine, then everything broke at once.” These failures don’t mean caching is bad—they mean caches concentrate traffic patterns, so small changes can trigger big effects.

After a deploy, autoscale event, or cache flush, you may have a mostly empty cache. The next burst of traffic forces many requests to hit the database or upstream APIs directly.

This is especially painful when traffic ramps quickly, because the cache hasn’t had time to warm with popular items. If deploys coincide with peak usage, you can accidentally create your own load test.

A stampede happens when many users request the same item right as it expires (or isn’t cached yet). Instead of one request recomputing the value, hundreds or thousands do—overwhelming the origin.

Common mitigations include:

If correctness requirements allow it, stale-while-revalidate can also smooth peaks.

Some keys become disproportionately popular (a homepage payload, a trending product, a global configuration). Hot keys create uneven load: one cache node or one backend path gets hammered while others stay idle.

Mitigations include splitting large “global” keys into smaller ones, adding sharding/partitioning, or caching at a different layer (for example, moving truly public content closer to users via a CDN).

Cache outages can be worse than no cache, because applications may be written to depend on it. Decide ahead of time:

Whatever you choose, rate limits and circuit breakers help prevent a cache failure from becoming an origin outage.

Caching can reduce load on your origin systems, but it increases the number of services you operate day to day. Even “managed” caches still require planning, tuning, and incident response.

A new caching layer is often a new cluster (or at least a new tier) with its own capacity limits. Teams must decide memory sizing, eviction policy, and what happens under pressure. If the cache is undersized, it churns: hit rate drops, latency rises, and the origin gets hammered anyway.

Caching rarely lives in one place. You might have a CDN cache, an application cache, and database caching—all interpreting rules differently.

Small mismatches compound:

Over time, “why is this request cached?” becomes an archaeology project.

Caches create recurring work: warming critical keys after deploys, purging or revalidating when data changes, resharding when nodes are added/removed, and rehearsing what happens after a full flush.

When users report stale data or sudden slowness, responders now have multiple suspects: the CDN, the cache cluster, the app’s cache client, and the origin. Debugging often means checking hit rates, eviction spikes, and timeouts across layers—then deciding whether to bypass, purge, or scale.

Caching is only a win if it reduces backend work and improves user-perceived speed. Because requests can be served by multiple layers (edge/CDN, application cache, database cache), you need observability that answers:

A high hit ratio sounds good, but it can hide problems (like slow cache reads or constant churn). Track a small set of metrics per layer:

If hit ratio rises but total latency doesn’t improve, the cache may be slow, overly serialized, or returning oversized payloads.

Distributed tracing should show whether a request was served at the edge, by the app cache, or by the database. Add consistent tags like cache.layer=cdn|app|db and cache.result=hit|miss|stale so you can filter traces and compare hit-path vs. miss-path timing.

Log cache keys carefully: avoid raw user identifiers, emails, tokens, or full URLs with query strings. Prefer normalized or hashed keys and log only a short prefix.

Alert on abnormal miss-rate spikes, sudden latency jumps on misses, and stampede signals (many concurrent misses for the same key pattern). Separate dashboards into edge, app, and database views, plus one end-to-end panel that ties them together.

Caching is great at repeating answers quickly—but it can also repeat the wrong answer to the wrong person. Caching-related security incidents are often silent: everything looks fast and healthy while data is leaking.

A common failure is caching personalized or confidential content (account details, invoices, support tickets, admin pages). This can happen at any layer—CDN, reverse proxy, or application cache—especially with broad “cache everything” rules.

Another subtle leak: caching responses that include session state (for example, a Set-Cookie header) and serving that cached response to other users.

A classic bug is caching the HTML/JSON returned for User A and later serving it to User B because the cache key didn’t include user context. In multi-tenant systems, tenant identity must be part of the key as well.

Rule of thumb: if the response depends on authentication, roles, geography, pricing tier, feature flags, or tenant, your cache key (or bypass logic) must reflect that dependency.

HTTP caching behavior is heavily driven by headers:

Cache-Control: prevent accidental storage with private / no-store where neededVary: ensure caches separate responses by relevant request headers (e.g., Authorization, Accept-Language)Set-Cookie: often a sign the response should not be cached publiclyIf compliance or risk is high—PII, health/financial data, legal documents—prefer Cache-Control: no-store and optimize server-side instead. For mixed pages, cache only non-sensitive fragments or static assets, and keep personalized data out of shared caches.

Caching layers can cut origin load, but it’s rarely “free performance.” Treat each new cache as an investment: you’re buying lower latency and less backend work in exchange for money, engineering time, and a larger correctness surface.

Extra infrastructure cost vs. reduced origin cost. A CDN might reduce egress and database reads, but you’ll pay for CDN requests, cache storage, and sometimes invalidation calls. An application cache (Redis/Memcached) adds cluster cost, upgrades, and on-call burden. Savings may show up as fewer database replicas, smaller instance types, or delayed scaling.

Latency wins vs. freshness costs. Every cache introduces a “how stale is acceptable?” decision. Strict freshness requires more invalidation plumbing (and more misses). Tolerated staleness saves compute but can cost user trust—especially for prices, availability, or permissions.

Engineering time: feature velocity vs. reliability work. A new layer usually means extra code paths, more testing, and more incident classes to prevent (stampedes, hot keys, partial invalidation). Budget ongoing maintenance, not just initial implementation.

Before rolling out broadly, run a limited trial:

Add a new caching layer only if:

Caching pays off fastest when you treat it like a product feature: it needs an owner, clear rules, and a safe way to turn it off.

Add one caching layer at a time (e.g., CDN or application cache first), and assign a directly responsible team/person.

Define who owns:

Most cache bugs are really “key bugs.” Use a documented convention that includes the inputs that change the response: tenant/user scope, locale, device class, and relevant feature flags.

Add explicit key versioning (e.g., product:v3:...) so you can invalidate safely by bumping a version rather than trying to delete millions of entries.

Trying to keep everything perfectly fresh pushes complexity into every write path.

Instead, decide what “acceptably stale” means per endpoint (seconds, minutes, or “until next refresh”), then encode it with:

Assume the cache will be slow, wrong, or down.

Use timeouts and circuit breakers so cache calls can’t take down your request path. Make graceful degradation explicit: if cache fails, fall back to origin with rate limits, or serve a minimal response.

Ship caching behind a canary or percentage rollout, and keep a bypass switch (per route or header) for fast troubleshooting.

Document runbooks: how to purge, how to bump key versions, how to disable caching temporarily, and where to check metrics. Link them from your internal runbooks page so on-call can act quickly.

Caching work often stalls because changes touch multiple layers (headers, app logic, data models, and rollback plans). One way to reduce the iteration cost is to prototype the full request path in a controlled environment.

With Koder.ai, teams can quickly spin up a realistic app stack (React on the web, Go backends with PostgreSQL, and even Flutter mobile clients) from a chat-driven workflow, then test caching decisions (TTL, key design, stale-while-revalidate) end to end. Features like planning mode help document the intended caching behavior before implementation, and snapshots/rollback make it safer to experiment with cache configuration or invalidation logic. When you’re ready, you can export source code or deploy/host with custom domains—useful for performance trials that need to mirror production traffic patterns.

If you do use a platform like this, treat it as a complement to production-grade observability: the goal is faster iteration on caching design while keeping correctness requirements and rollback procedures explicit.

Caching reduces load by answering repeat requests without hitting your origin (app servers, databases, third-party APIs). The biggest gains usually come from:

The earlier in the request path a cache hits (browser/CDN vs app), the more origin work you avoid.

A single cache is one store (e.g., an in-memory cache next to your app). A caching layer is a checkpoint in the request path (browser cache, CDN, reverse proxy, app cache, database cache).

Multiple layers reduce load more broadly, but they also introduce more rules, more failure modes, and more ways to serve inconsistent data when layers disagree.

Misses trigger real work plus caching overhead. On a miss you typically pay for:

So a miss can be slower than “no cache” unless the cache is well-designed and the hit rate is high on the endpoints that matter.

TTL is easy because it doesn’t require coordination, but it forces a guess about freshness. If TTL is too long, you serve stale data; too short, you don’t reduce load much.

A practical approach is to set TTLs per feature based on user impact (e.g., minutes for docs pages, seconds or no-cache for balances/pricing) and revisit them using real hit/miss and incident data.

Use event-driven invalidation when staleness is costly and you can reliably connect writes to affected cache keys. It works best when:

If you can’t guarantee those, prefer bounded staleness (TTL + revalidation) over “perfect” invalidation that silently fails.

Multi-layer caching can make different parts of the system disagree. Example: the CDN serves old HTML while the app cache serves newer JSON, creating a mixed UI.

To reduce this:

product:v3:...) so reads move forward safelyVary/headers match what actually changes the responseA stampede (thundering herd) happens when many requests rebuild the same key at once (often right after expiry), overwhelming the origin.

Common mitigations:

Decide the fallback behavior ahead of time:

Also add timeouts, circuit breakers, and rate limits so a cache outage doesn’t cascade into an origin outage.

Focus on metrics that explain outcomes, not just hit ratio:

In tracing/logs, tag requests with cache.layer and cache.result so you can compare “hit path” vs “miss path” and spot regressions quickly.

The most common risk is caching personalized or confidential responses in shared layers (CDN/reverse proxy) due to missing key variation or bad headers.

Safeguards:

Cache-Control: private or no-store for sensitive responsesVary (e.g., Authorization, Accept-Language) when responses differSet-Cookie on a response as a strong signal to avoid public caching