Aug 15, 2025·8 min

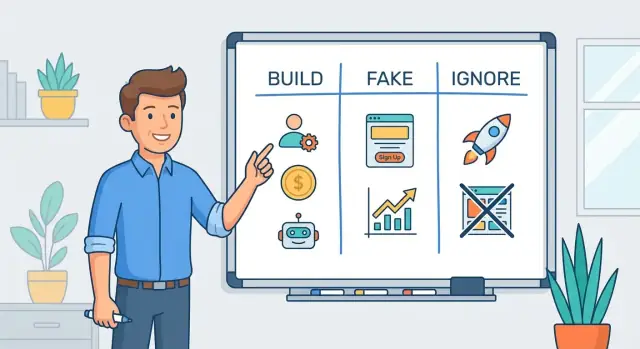

MVPs in 2025: What to Build, Fake, or Ignore as a Founder

A practical 2025 guide to MVP thinking: decide what to build, what to fake safely, and what to ignore so you can validate demand and ship faster.

A practical 2025 guide to MVP thinking: decide what to build, what to fake safely, and what to ignore so you can validate demand and ship faster.

An MVP in 2025 isn’t “the smallest version of your product.” It’s the smallest test of your business that can produce a clear learning outcome. The point is to reduce uncertainty—about the customer, the problem, willingness to pay, or the channel—not to ship a trimmed-down roadmap.

If your MVP can’t answer a specific question (e.g., “Will busy clinic managers pay $99/month to reduce no-shows?”), it’s likely just early product development wearing an MVP label.

MVP is: a focused experiment that delivers a real outcome for a narrowly defined user, so you can measure demand and behavior.

MVP is not: a mini product, a feature checklist, or a “v1” you secretly hope to scale. It’s also not an excuse for sloppy quality in the one thing you’re testing. You can be minimal and still be credible.

Move fast, but be deliberate:

Treat the MVP as a learning tool and you earn the right to ignore distractions—each iteration becomes sharper, not just bigger.

An MVP only works if it’s aimed at a specific person with a specific problem that already has urgency. If you can’t name who it’s for and what changes in their day after using it, you’re not building an MVP—you’re collecting features.

Start by describing a single, real customer type—not “small businesses” or “creators,” but someone you could recognize in the wild.

Ask:

If urgency is missing, validation will be slow and noisy—people will be “interested” without changing behavior.

Write a promise that connects customer + job + outcome:

“For [specific customer], we help you [complete job] so you can [measurable outcome] without [main sacrifice or risk].”

This sentence is your filter: anything that doesn’t strengthen it is probably not in the MVP.

Your MVP should deliver one undeniable moment where the user thinks: “This works.”

Examples of an “aha” moment:

Make it observable: what does the user see, click, or receive?

Your competitor is usually a workaround:

Knowing the alternative clarifies your MVP: you’re not trying to be perfect—you’re trying to be a better trade-off than what they already rely on.

An MVP is only useful if it answers a specific question that changes what you do next. Before you design screens or write code, translate your idea into hypotheses you can test—and decisions you’re willing to make.

Write them as statements you can prove or disprove within days or weeks:

Keep the numbers imperfect but explicit. If you can’t add a number, you can’t measure it.

Your MVP should prioritize the biggest uncertainty. Examples:

Choose one. Secondary questions are fine only if they don’t slow the primary test.

Decide in advance what results mean:

Avoid goals like “get feedback.” Feedback is only valuable when it triggers a decision.

Your MVP should deliver value once, end-to-end, for a real person. Not “most of the product.” Not “a demo.” One completed journey where the user gets the outcome they came for.

Ask: When someone uses this, what changes for them by the end of the session? That change is your outcome. The MVP is the shortest path that reliably produces it.

To deliver the outcome once, you typically need only a few “real” components:

Everything else is supporting infrastructure you can postpone.

Separate the core workflow from common supporting features like accounts, settings, roles, admin dashboards, notifications, preference management, integrations, and full analytics suites. Many MVPs only need lightweight tracking and a manual back office.

Choose a single user type, a single scenario, and a single success definition. Handle edge cases later: unusual inputs, complex permissions, retries, cancellations, multi-step customization, and rare errors.

A “thin vertical slice” means you build a narrow end-to-end path through the whole experience—just enough UI, logic, and delivery to complete the job once. It’s small, but it’s real, and it teaches you what users actually do.

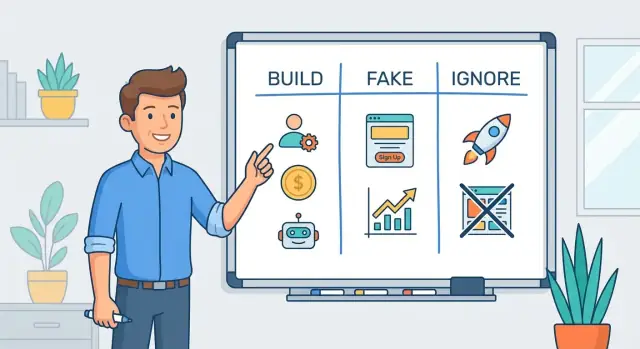

Speed isn’t about cutting corners everywhere—it’s about cutting corners in places that don’t change the customer’s decision. The goal of “faking” in an MVP is to deliver the promised outcome quickly, then learn whether people want it enough to return, recommend it, or pay for it.

A concierge MVP is often the fastest way to test value: you do the work manually, and customers experience the result.

For example, instead of building a full matching algorithm, you can ask a few onboarding questions and hand-pick results yourself. The user still gets the core outcome; you learn what “good” looks like, what inputs matter, and what edge cases appear.

With Wizard-of-Oz, the product appears automated, but a person is operating it behind the scenes. This is useful when automation is expensive but you need to test the interaction model.

Keep the experience honest in practice: set expectations on turnaround times, avoid implying real-time automation if you can’t deliver it, and document every manual step so you can later decide what to automate first.

Seeded content can prevent an empty-product problem. A marketplace can start with a curated catalog; a dashboard can show simulated history to demonstrate how insights will look.

Rules of thumb:

Don’t build custom infrastructure for things customers don’t choose you for. Use templates for landing pages and onboarding, no-code for internal tools, and off-the-shelf components for scheduling, email, and analytics. Save engineering time for the one thing that makes your offer meaningfully better.

Some shortcuts create irreversible damage:

Fake the automation, not the responsibility.

Early on, your job isn’t to build a “real product.” It’s to reduce uncertainty: do the right people have this problem, and will they change behavior (or pay) to solve it? Anything that doesn’t answer those questions is usually an expensive distraction.

A clean UI helps, but weeks spent on brand systems, animations, illustration packs, and pixel-perfect screens rarely change the core signal.

Do the minimum that communicates credibility: clear copy, consistent spacing, working forms, and obvious contact/support. If users won’t try it when it looks “decent,” a full rebrand won’t save it.

Building web + iOS + Android sounds like “meeting users where they are.” In practice, it’s three codebases and triple the surface area for bugs.

Pick one channel that matches your audience’s habit (often a simple web app) and validate there first. Port only after you see repeat usage or paid conversion.

Role-based access, admin panels, and internationalization are legitimate needs—just not Day 1 needs.

Unless your first customers are explicitly enterprises or global teams, treat these as future requirements. You can start with a single “owner” role and manual workarounds.

Optimizing for millions of users before you have dozens is a classic trap.

Choose boring, simple architecture that you can change quickly. You need reliability for experiments, not distributed systems.

Dashboards feel productive, but they often measure everything except what matters.

Start by defining one or two behaviors that indicate real value (e.g., repeat use, completed outcome, payment). Track them simply—spreadsheet, basic events, even manual logs—until the signal is clear.

An MVP is only as useful as the experiment wrapped around it. If you don’t decide who you’ll talk to, what you’ll ask, and what would change your mind, you’re not validating—you’re collecting vibes.

Start with the channel you can actually execute this week:

Decide your target segment up front (role + context + trigger). “Small businesses” isn’t a segment; “US-based wedding photographers who spend 3+ hours/week on client follow-ups” is.

For early-stage MVPs, aim for a sample that can reveal patterns, not produce statistical certainty.

A practical rule: 8–12 conversations in one consistent segment to find repeating problems, then 5–10 structured trials (demo/prototype/concierge) to see if people take the next step.

Your script should include:

Run experiments in days or 1–2 week blocks. Before you start, write down:

This keeps your MVP focused on learning—not endless building.

Early MVP feedback is noisy because people are polite, curious, and often optimistic. The goal is to measure behavior that costs them something: time, effort, reputation, or money. If your metrics don’t force a trade-off, they won’t predict demand.

Activation is the first action that proves the user received the core outcome—not that they clicked around.

For example: “created a first report and shared it,” “booked the first appointment,” or “completed the first workflow end-to-end.” Define it as a single, observable event and track the activation rate from each acquisition channel.

Retention isn’t “they opened the app again.” It’s repeating the value action on a cadence that matches the problem.

Set a time window that fits reality: daily for habit products, weekly for team workflows, monthly for finance/admin tasks. Then ask: Do activated users repeat the core action without being chased? If retention depends on constant reminders, your product may be a service—or the value isn’t strong enough yet.

Strong signals include pre-orders, deposits, paid pilots, and paid onboarding. LOIs can help, but treat them as a weak signal unless they include specific scope, timeline, and a clear path to payment.

If users won’t pay yet, test willingness to pay with pricing pages, checkout flows, or “request invoice” steps—then follow up and ask what stopped them.

Look for consistency across conversations:

When activation, retention, and payment intent move together, you’re not just hearing interest—you’re seeing demand.

AI can be a force-multiplier in an MVP—when it reduces time-to-learning. The trap is using “AI-powered” as a blanket to cover unclear requirements, weak data, or a fuzzy value proposition. Your MVP should make uncertainty visible, not bury it.

Use AI when it accelerates cycles of feedback:

If AI doesn’t shorten the path to seeing whether users get the outcome, it’s probably scope.

Model output is probabilistic. In an MVP, that means errors will happen—and they can destroy trust before you’ve learned anything. Avoid “fully automated” claims unless you can reliably measure quality and recover from failures.

Practical safeguards:

Tell users what the AI does, what it doesn’t, and how to correct it. A simple “review and approve” step can protect trust and create useful training data.

Finally, don’t rely on the model itself as your moat. Differentiate through proprietary data, a workflow people adopt daily, or distribution (a channel you can reach consistently). The MVP goal: prove that combination creates repeatable value.

Your MVP tech stack is a temporary decision-making system. The best choice isn’t what scales forever—it’s what lets you change your mind quickly without breaking everything.

Prefer a “boring” baseline: one app, one database, one queue (or none), and a clean separation between UI and core logic. Avoid microservices, event-driven everything, or heavy internal tooling until you’ve proven the workflow is worth keeping.

A simple rule: if a component doesn’t reduce learning time, it’s likely increasing it.

Pick providers that remove entire categories of work:

This keeps your MVP focused on the core product decision rather than plumbing.

If your bottleneck is turning a validated flow into a working vertical slice, a vibe-coding platform like Koder.ai can help you move from “spec” to “usable app” faster—especially for the first end-to-end path.

Because Koder.ai builds web apps (React) and backends (Go + PostgreSQL) via a chat interface—plus supports planning mode, source code export, deployment/hosting, and snapshots/rollback—you can iterate on the core flow quickly without locking yourself into premature infrastructure. The key is to use that speed to run more experiments, not to expand scope.

Speed doesn’t mean careless. Minimum bar:

Instead of guessing when to rewrite, define triggers up front: e.g., “3+ weekly deployments blocked by architecture,” “we changed the core workflow twice,” or “support time exceeds X hours/week due to data model limits.” When a trigger hits, rebuild one layer at a time—not the whole product.

If your MVP only proves that people are curious, you’re still guessing. In 2025, a startup MVP should test whether the problem is painful enough that someone will pay to make it go away.

Skip the “Would you pay for this?” conversation. Instead, present a clear offer: what they get, what it costs, and what happens next. Even for a concierge MVP, you can send a simple proposal or checkout link and ask them to choose a plan.

Good signals include asking for an invoice, requesting procurement steps, negotiating terms, or committing to a pilot start date.

Early on, keep packages few and easy to compare. Tie each package to the result the customer wants—speed, certainty, saved time, reduced risk—rather than a list of tools.

For example, instead of “Basic includes 3 reports,” consider:

This helps you learn which outcome is the real hook and which customers value speed vs. autonomy.

Pick a pricing model that matches the value you’re creating:

You can revise later, but you need a starting point to validate willingness to pay.

Free can help distribution, but only if it leads predictably to paid: a time limit, a usage cap, or a feature that naturally upgrades. Otherwise you’ll attract the wrong feedback—people who like “free,” not people who need your solution.

An MVP without go-to-market is just a prototype you like. In 2025, your “minimum” should include a repeatable way to reach people, learn from them, and adjust weekly.

Keep it brutally simple:

reach → interest → trial → value → paid

Define each step in one sentence. Example: reach = saw the post; interest = clicked and left email; trial = booked a call; value = got the promised outcome; paid = started a subscription. If you can’t observe a step, it doesn’t exist.

Choose a single distribution channel for the first sprint—LinkedIn outbound, a niche community, cold email, partnerships, or ads. One channel forces clarity: message, audience, offer.

Set a small weekly target (e.g., 50 outreaches, 10 conversations, 3 trials). Track it in a simple sheet. If the channel doesn’t produce conversations, you don’t have a product problem yet—you have a reach problem.

Make learning unavoidable:

Then translate feedback into a single decision for the next experiment.

An MVP in 2025 is the smallest test that produces a clear learning outcome (e.g., demand, willingness to pay, retention driver, channel viability). It should answer one primary question that changes your next decision—not ship a trimmed roadmap.

A prototype proves usability/understanding (often without real users or real outcomes). An MVP delivers the core outcome end-to-end (even if manual behind the scenes) to test value and buying behavior. If nobody can complete the promised outcome, you built a demo—not an MVP.

A pilot is a controlled rollout with a specific customer/group, higher-touch support, and explicit success criteria. A beta is broader access to a near-ready product to find bugs, edge cases, and adoption friction. Use beta after you already know the problem matters; use a pilot when you want proof in a real environment with clear measurement.

Use the one-sentence promise:

“For [specific customer], we help you [job] so you can [measurable outcome] without [main sacrifice/risk].”

If you can’t fill this in concretely, your MVP scope will drift and your results will be hard to interpret.

It’s the first observable moment where the user thinks “this works” because the promised change happened.

Examples:

Define it as a single event you can track (not a feeling).

Start with 2–3 testable hypotheses and put numbers on them:

Then choose one primary question (e.g., “Will they pay?”) and design the MVP to answer it fast.

Build only what’s required to deliver the outcome once, end-to-end:

Delay accounts, roles, dashboards, integrations, edge cases, and heavy analytics until you see real demand.

Fake automation when it doesn’t change the customer’s decision:

Don’t fake security/privacy, billing accuracy, or legal/compliance—those shortcuts can create irreversible damage.

Prefer signals that cost users something:

Compliments and “this is cool” feedback are weak unless they lead to commitment.

Use pricing as an experiment, not a debate. Present a real offer (scope + price + next step) and measure behavior:

Package around outcomes (speed, certainty, saved time, reduced risk) rather than feature counts so you learn what customers truly value.