Nov 26, 2025·8 min

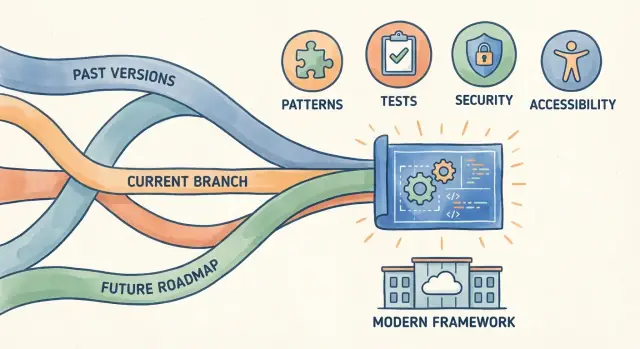

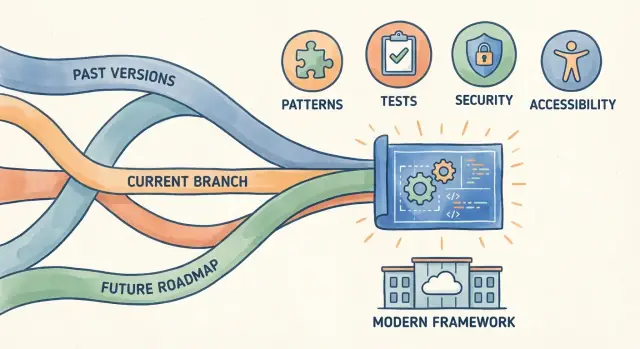

How Frameworks Preserve and Encode Best Practices Over Time

Frameworks capture lessons from past projects—patterns, defaults, and conventions. Learn how they encode best practices, where they can fail, and how to use them well.

Frameworks capture lessons from past projects—patterns, defaults, and conventions. Learn how they encode best practices, where they can fail, and how to use them well.

“Best practices from the past” aren’t dusty rules from old blog posts. In practical terms, they’re the hard-won decisions teams made after seeing the same failures repeat: security mistakes, inconsistent codebases, brittle deployments, slow debugging, and features that were painful to change.

Frameworks feel like “experience in a box” because they bundle those lessons into the normal path of building software. Instead of asking every team to reinvent the same answers, frameworks turn common decisions into defaults, conventions, and reusable building blocks.

Convenience is real—scaffolding a project in minutes is nice—but frameworks aim for something bigger: predictability.

They standardize how you structure an app, where code lives, how requests flow, how errors are handled, and how components talk to each other. When a framework does this well, new team members can navigate faster, code reviews focus on meaningful choices (not style disputes), and production behavior becomes easier to reason about.

Frameworks encode guidance, but they don’t guarantee good outcomes. A secure default can be bypassed. A recommended pattern can be misapplied. And a “best practice” from five years ago might be a poor fit for your constraints today.

The right mental model is: frameworks reduce the number of decisions you must make—and raise the baseline quality of the decisions you don’t make on purpose. Your job is to recognize which decisions are strategic (domain modeling, data boundaries, scaling needs) and which are commodity (routing, validation, logging).

Over time, frameworks capture lessons in several ways: sensible defaults, conventions, built-in architectural patterns, security guardrails, testing tooling, and standardized performance/observability hooks. Understanding where those lessons live helps you use them confidently—without treating the framework as unquestionable truth.

People often use “framework” and “library” interchangeably, but they influence your project in very different ways.

A library is something you call when you need it. You choose when to use it, how to wire it in, and how it fits your code. A date library, a PDF library, or a logging library typically works this way.

A framework is something that calls you. It provides the overall structure of the app and expects you to plug your code into its predefined places.

A toolkit is a looser bundle of utilities (often multiple libraries plus conventions) that helps you build faster, but usually doesn’t control your app’s flow as strongly as a framework.

Frameworks rely on inversion of control: instead of your program being the “main loop” that invokes everything else, the framework runs the main loop and invokes your handlers at the right time.

That single design choice forces (and simplifies) many decisions: where routes live, how requests are processed, how dependencies are created, how errors are handled, and how components are composed.

Because the framework defines the skeleton, teams spend less time re-deciding basic structure on every project. That reduces:

Consider a web app.

With a library approach, you might pick a router, then separately choose a form validation package, then hand-roll session handling—deciding how they interact, where state is stored, and what errors look like.

With a framework, routing may be defined by a file/folder convention or a central route table, forms may have a standard validation lifecycle, and authentication may integrate with built-in middleware. You’re still making choices, but many defaults are already selected for you—often reflecting hard-earned lessons about clarity, safety, and long-term maintainability.

Frameworks rarely start out as “best practices.” They start as shortcuts: a small set of utilities built for one team, one product, and one set of deadlines. The interesting part is what happens after version 1.0—when dozens (or thousands) of real projects begin pushing the same edges.

Over time, a pattern repeats:

Projects hit the same problems → teams invent similar solutions → maintainers notice the repetition → the framework standardizes it as a convention.

That standardization is what makes frameworks feel like accumulated experience. A routing style, folder structure, migration mechanism, or error-handling approach often exists because it reduced confusion or prevented bugs across many codebases—not because someone designed it perfectly upfront.

Many “rules” in a framework are memorials of past failures. A default that blocks unsafe input, a warning when you do something risky, or an API that forces explicit configuration often traces back to incidents: production outages, security vulnerabilities, performance regressions, or hard-to-debug edge cases.

When enough teams trip over the same rake, the framework will often move the rake—or put up a sign.

Maintainers decide what becomes official, but the raw material comes from usage: bug reports, pull requests, incident write-ups, conference talks, and what people build plugins for. Popular workarounds are especially telling—if everyone adds the same middleware, it may become a first-class feature.

What’s considered best practice depends on constraints: team size, compliance needs, deployment model, and current threats. Frameworks evolve, but they also carry history—so it’s worth reading upgrade notes and deprecation guides (see /blog) to understand why a convention exists, not just how to follow it.

Framework defaults are quiet teachers. Without a meeting, a checklist, or a senior developer hovering over every decision, they steer teams toward choices that have worked well before. When you create a new project and it “just works,” that’s usually because someone encoded a pile of hard-won lessons into the starting settings.

Defaults reduce the number of decisions you need to make on day one. Instead of asking “What should our project structure be?” or “How should we configure security headers?”, the framework offers a starting point that encourages a safe, consistent baseline.

That nudge matters because teams tend to stick with what they start with. If the initial setup is sensible, the project is more likely to stay sensible.

Many frameworks ship with safe configuration out of the box: development mode that’s clearly separated from production mode, secrets loaded from environment variables, and warnings when unsafe settings are detected.

They also provide a sensible folder structure—for routes, controllers, views, components, tests—so new contributors can find things quickly and avoid inventing a new organization system every sprint.

And plenty are opinionated about setup: one “blessed” way to start an app, run migrations, handle dependency injection, or register middleware. That can feel restrictive, but it prevents a lot of early chaos.

Beginners often don’t know which decisions are risky, or which “quick fixes” become long-term problems. Safe defaults make the easy path a safer path: fewer accidental exposures, fewer inconsistent conventions, and fewer brittle one-off setups.

Defaults reflect the framework authors’ assumptions. Your domain, compliance requirements, traffic patterns, or deployment model may differ. Treat defaults as a starting baseline, not as proof of correctness—review them explicitly, document any changes, and revisit them when you upgrade or your needs change.

Framework conventions are often described as “convention over configuration,” which basically means: you agree to the house rules so you don’t have to negotiate every detail.

A relatable analogy is a grocery store. You don’t need a map to find milk because most stores place dairy in a familiar area. The store could put milk anywhere, but the shared convention saves time for everyone.

Conventions show up as default answers to questions teams would otherwise debate:

User vs Users, getUser() vs fetchUser()—frameworks nudge a consistent style.When these conventions are widely adopted, a new developer can “read” a project faster. They know where to look for the login flow, where validation happens, and how data moves through the app, even if they’ve never seen this codebase before.

Predictable structure reduces small decisions that drain time and attention. It also improves onboarding, makes code reviews smoother (“this matches the usual pattern”), and helps teams avoid accidental inconsistencies that later become bugs or maintenance headaches.

Conventions can limit flexibility. Edge cases—unusual routing needs, multi-tenant data models, non-standard deployments—may fight the default project shape. When that happens, teams may either pile on workarounds or bend the framework in ways that confuse future maintainers. The goal is to follow conventions where they help, and document clearly when you must diverge.

Frameworks don’t just give you tools—they embed a preferred way to structure software. That’s why a new project can feel “organized” before you’ve made many decisions: common patterns are already reflected in folder layouts, base classes, routing rules, and even method names.

Many frameworks ship with a default architecture like MVC (Model–View–Controller), encouraging you to separate UI, business logic, and data access. Others push dependency injection (DI) by making services easy to register and easy to consume, so code depends on interfaces rather than concrete implementations. Web frameworks often standardize request handling through middleware, turning cross-cutting concerns (auth, logging, rate limiting) into composable steps.

These patterns reduce “blank page” design work and make projects easier to navigate—especially for teams. When the structure is predictable, it’s simpler to add features without breaking unrelated parts.

Patterns create natural seams.

With MVC, controllers become thin entry points you can test with request/response fixtures. With DI, you can swap real dependencies for fakes in unit tests without rewriting code. Middleware makes behavior easy to verify in isolation: you can test a single step without spinning up the entire app.

A pattern can turn into ceremony when it doesn’t match the problem. Examples: forcing everything into services when a simple function would do; splitting files into “layers” that mostly pass data through; adding middleware for behavior that belongs in a single endpoint.

Frameworks often “remember” security incidents so teams don’t have to relearn them the hard way. Instead of expecting every developer to be a security expert, they ship guardrails that make the safer choice the default—and make risky choices more deliberate.

A lot of day-to-day security best practices show up as ordinary framework features:

HttpOnly, Secure, and SameSite cookies.These features encode lessons learned from common attack patterns (tampering, cross-site requests, session theft) and move them closer to “standard plumbing.”

Security fixes often arrive through routine updates. Keeping framework and dependency versions current matters because many patches don’t change your code—just your exposure.

The biggest risk is accidental opt-out. Common misconfigurations include:

Treat framework security defaults as a baseline, not a guarantee, and review changes during upgrades instead of postponing them indefinitely.

Frameworks don’t just make it easier to write code—they make it easier to prove that code keeps working. Over time, communities encode hard-won testing habits into default project structure, commands, and integrations, so quality practices feel like the normal way to build.

Many frameworks scaffold a predictable layout—separating app code, configuration, and tests—so adding tests is an obvious next step, not a separate initiative. A built-in test command (often a single CLI entry point) also lowers the “activation energy” of running tests locally and in CI.

Common tooling baked in or tightly integrated includes:

The result is subtle but powerful: the framework’s “happy path” quietly aligns with practices teams had to learn the hard way.

Quality also depends on consistency. Framework tooling often standardizes configuration loading, environment variables, and test databases so that tests behave the same on a laptop and in CI. When a project has a canonical way to start services, seed data, and run migrations, failures become debuggable rather than mysterious.

A simple rule of thumb: if a new teammate can run test successfully after following a short README, you’ve reduced a major source of hidden defects.

Keep it practical:

Frameworks can’t guarantee quality, but good tooling turns disciplined testing into a default habit rather than an ongoing argument.

Frameworks don’t just help you ship features—they quietly set expectations for how an app should behave under load and how you’re supposed to understand it when it misbehaves.

Many performance practices arrive implicitly through defaults and idioms rather than a checklist. Common examples include caching layers (response caching, ORM query caching), batching work (bulk database writes, request coalescing), and lazy loading (only fetching data when a page/component actually needs it). Even “small” conveniences—like connection pooling or sane pagination helpers—encode years of lessons about what tends to hurt performance first.

That said, there’s an important difference between fast by default and fast at scale. A framework can make the first version of your app snappy with sensible defaults, but real scale often requires deeper choices: data modeling, queueing strategies, read/write separation, CDN usage, and careful control over N+1 queries and chatty network calls.

Modern frameworks increasingly include built-in or first-class integrations for observability: structured logging, metrics exporters, and tracing hooks that propagate request IDs across services. They may provide standard middleware/interceptors to log request timing, capture exceptions, and attach contextual fields (user ID, route name, correlation ID).

If your framework ships “blessed” integrations, use them—standardization makes dashboards and on-call runbooks more transferable between projects.

Framework conventions can guide you toward safer defaults, but they can’t guess your bottleneck. Profile and measure (latency percentiles, database time, queue depth) before rewriting code or turning knobs. Performance work is most effective when it’s driven by evidence, not instinct.

Frameworks don’t just add features—they rewrite “the right way” to build. Over time, that evolution shows up as deprecations, new defaults, and sometimes breaking changes that force you to revisit assumptions your team made years ago.

A common pattern is: a practice becomes popular, the framework standardizes it, and later the framework replaces it when new risks or better techniques appear. Deprecations are the framework’s way of saying, “This used to be fine, but we’ve learned more.” New defaults often push safer behavior (for example, stricter input validation or safer cookie settings), while breaking changes remove escape hatches that kept old patterns alive.

What was once a best practice can turn into a constraint when:

This can create “framework debt”: your code still works, but it’s increasingly expensive to maintain, harder to hire for, and riskier to secure.

Treat upgrades as a continuous activity, not a rescue mission:

Stay (for now) if you have stable requirements, strong mitigations, and a clear end-of-life plan. Move when security support is ending, upgrades are becoming “all-or-nothing,” or new defaults would meaningfully reduce risk and maintenance cost.

Frameworks don’t “decide” best practices on their own. The community around them—maintainers, core contributors, major users, and tool authors—gradually converges on what feels safe, maintainable, and widely applicable. Over time, those decisions solidify into defaults, recommended project structures, and official APIs.

Most standards start as repeated solutions to common pain. When many teams hit the same problems (routing complexity, auth mistakes, inconsistent error handling), the community tests approaches in real projects, debates trade-offs in issues and RFCs, and refines them through releases.

What survives tends to be:

Ecosystems often experiment at the edges first. Plugins, extensions, and third-party packages let new ideas compete without forcing everyone to upgrade immediately. If a plugin becomes popular and its approach keeps working across versions, it may be adopted into the core framework—or at least heavily promoted in official guidance.

Docs are not just reference material; they’re behavioral nudges. “Getting started” tutorials, starter templates, and official example repos quietly define what “normal” looks like: folder layout, naming conventions, testing style, even how to structure business logic.

If you use a generator or starter kit, you’re inheriting those opinions—often beneficial, sometimes limiting.

Community standards move. Defaults change, old APIs get discouraged, and new security or performance guidance appears. Skimming official docs and release notes before upgrading (or adopting a new major version) helps you understand why conventions changed and which migrations are non-negotiable.

Frameworks can save years of trial and error—but they also encode assumptions. Using them well means treating a framework as a set of defaults to learn, not a substitute for product thinking.

Start by matching the framework to your situation:

Before committing, list what the framework decides and what you can opt out of:

Use the framework’s conventions where they help consistency, but avoid rewriting it to match your old habits. If you need major deviations (custom project structure, replacing core components), that’s a signal you may be choosing the wrong tool—or that you should isolate customizations behind a thin layer.

A practical way to pressure-test this: prototype one critical flow end-to-end (auth → data write → background work → UI update), and see how much “glue” you had to invent. The more glue you need, the more you’re likely working against the framework’s accumulated assumptions.

Frameworks encode experience; the challenge is figuring out which conventions you want to inherit before you’ve invested months into a codebase. Koder.ai can help you run that “small spike” faster: you can describe the app in chat, generate a working baseline (often a React front end with a Go + PostgreSQL backend, or a Flutter mobile app), and iterate in planning mode to make the framework-level decisions explicit.

Because Koder.ai supports source code export, snapshots, and rollback, you can experiment with different architectural conventions (routing styles, validation boundaries, auth middleware choices) without locking yourself into a single early guess. That makes it easier to adopt framework best practices deliberately—treating defaults as a starting point, while keeping the freedom to evolve as requirements become real.

A framework feels like “experience in a box” because it bundles repeated lessons from many projects into defaults, conventions, and built-in patterns. Instead of each team re-learning the same failures (security gaps, inconsistent structure, brittle deployments), the framework makes a safer, more predictable path the easiest path.

The key difference is inversion of control:

That control over the app’s “skeleton” is why frameworks decide more for you.

Predictability means a project has a standard shape and flow so production behavior and code navigation are easier to reason about.

In practice, frameworks standardize things like where code lives, how requests move through the system, how errors are handled, and how cross-cutting concerns (auth/logging) are applied—reducing surprises across environments and teams.

Frameworks tend to turn common pain into convention via a feedback loop:

That’s why many “rules” are effectively memorials of past outages, security incidents, or debugging nightmares.

Defaults quietly set your baseline because teams often keep the initial configuration.

Common examples include:

These reduce early decision load and prevent common beginner mistakes.

Not automatically. Defaults reflect the framework authors’ assumptions, which may not match your constraints (compliance, traffic patterns, deployment model).

A practical approach:

Conventions reduce time spent on low-value debates (naming, file placement, workflows) and improve:

They’re most valuable in team settings where consistency beats local optimization.

Common baked-in patterns include MVC, dependency injection, and middleware pipelines.

They help by creating clear seams:

The risk is adding ceremony (extra layers/indirection) when the problem doesn’t need it.

Framework guardrails commonly include:

HttpOnly, Secure, SameSite)They reduce risk, but only if you (e.g., disabling CSRF to “make the form work”) and if you to receive patches.

“Framework debt” is when your code still runs, but the framework’s older conventions and APIs make it harder to upgrade, secure, hire for, or operate.

To reduce it:

Move off old patterns when security support is ending or upgrades become all-or-nothing.