Apr 17, 2025·8 min

How JavaScript Took Over the Web, Backend, and Whole Companies

From browser scripts to Node.js servers, JavaScript’s rise reshaped tooling, hiring, and shipping products—making one language power whole companies.

From browser scripts to Node.js servers, JavaScript’s rise reshaped tooling, hiring, and shipping products—making one language power whole companies.

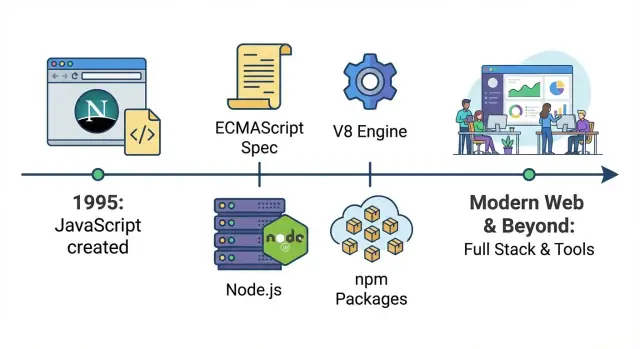

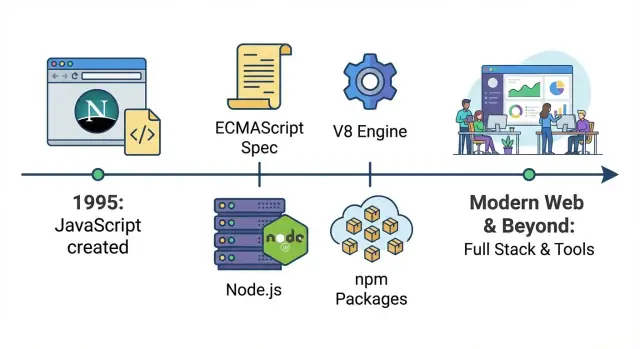

JavaScript started life as a way to add a bit of interactivity to webpages—small scripts that validated a form, swapped an image, or showed a dropdown. This guide tracks how that “little helper language” turned into a company-wide platform: the same core technology now runs user interfaces, servers, build systems, automation, and internal tools.

In practical terms, JavaScript is the one language every mainstream browser can execute directly. If you ship code to users without requiring them to install anything, JavaScript is the universal option. Other languages can participate—but usually by compiling to JavaScript or running on a server—while JavaScript runs at the destination by default.

First is the browser era, where JavaScript became the standard way to control the page: reacting to clicks, manipulating the DOM, and eventually powering richer experiences as the web moved beyond static documents.

Second is the backend era, where faster engines and Node.js made it practical to run JavaScript on servers. That unlocked a shared language across frontend and backend, plus a package ecosystem that accelerated reuse.

Third is the business operations era, where JavaScript tooling became “the glue”: build pipelines, testing, design systems, dashboards, automation scripts, and integrations. Even teams that don’t think of themselves as “JavaScript teams” often rely on JavaScript-based tools daily.

We’ll focus on major turning points—standardization, performance leaps, Node.js, npm, and the shift to framework-driven apps—rather than cataloging every library or trend.

JavaScript was created in 1995 at Netscape as a simple way to add interactivity to web pages without requiring a server round-trip or a full “software install.” Brendan Eich built the first version quickly, and its original goal was modest: let web authors validate forms, react to button clicks, and make pages feel less static.

Early web constraints shaped what JavaScript could be. Computers were slower, browsers were basic, and most sites were mostly text with a few images. Scripts had to be lightweight and forgiving—small snippets that could run without freezing the page.

Because pages were simple, early JavaScript often looked like “a little logic” sprinkled into HTML: checking whether an email field contained an @ sign, showing an alert, or swapping an image when you hovered a link.

Before this, a web page largely did what it said: it displayed content. With JavaScript embedded directly in the page, it could respond immediately to user actions. Even a tiny script could:

It was the start of the browser becoming an application runtime—not just a document viewer.

The downside was unpredictability. Browsers didn’t always interpret JavaScript the same way, and APIs for interacting with the page (early DOM behavior, event models, and element methods) varied widely. Developers had to write different code paths depending on the browser, test constantly, and accept that something working on one machine might break on another.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, browsers competed aggressively by shipping new features as fast as possible. Netscape and Internet Explorer didn’t just race on speed—they raced on JavaScript behaviors, DOM APIs, and proprietary extensions.

For developers, this meant the same script could work in one browser and break in another. You’d see bugs that weren’t “your fault”: different event models, missing methods, and inconsistent edge cases. Shipping a website often required writing two versions of the same logic, plus browser-detection hacks.

To reduce the chaos, JavaScript needed a shared definition that wasn’t controlled by a single browser vendor. That definition became ECMAScript—the standard that describes the core language (syntax, types, functions, objects, etc.).

A useful mental model:

Once vendors aligned on ECMAScript versions, the language became more predictable across browsers. Incompatibilities didn’t vanish overnight—APIs outside the language core (like parts of the DOM) still varied—but the foundation stabilized. Over time, better test suites and shared expectations made “works on my browser” less acceptable.

Even as ECMAScript evolved, backward compatibility became a non-negotiable promise: old sites should keep working. That’s why legacy patterns—var, odd equality rules, and pre-module workarounds—stayed in the ecosystem. The web couldn’t afford a hard reset, so JavaScript grew by adding new features rather than removing old ones.

Before Ajax, most websites behaved like paper forms: you click a link or submit a form, the browser reloads the entire page, and you wait for the server to send back a brand-new HTML document.

Ajax (short for “Asynchronous JavaScript and XML,” though JSON quickly became the real star) changed that pattern. With JavaScript, a page could request data from the server in the background and update only the part that needed changing—no full reload.

Ajax made the web feel less like a series of page loads and more like an interactive program. A search box could show suggestions as you type. A shopping cart total could update instantly. Comments could appear after you post them without kicking you back to the top of the page.

This wasn’t just a nicer interface—it reduced friction. People stopped tolerating “click → wait → reload” for every small action.

Products like Gmail demonstrated that the browser could handle app-like interactions: fast inbox updates, instant labeling, smooth navigation, and fewer interruptions. Once users experienced that responsiveness, it became the baseline expectation for other sites too.

Ajax nudged teams to separate “data” from “page.” Instead of sending a whole HTML page every time, servers increasingly exposed APIs that returned structured data (often JSON). The browser—powered by JavaScript—became a real client responsible for rendering, interactions, and state.

The downside was complexity. More application logic shifted into the browser: validation, UI state, caching, error handling, and performance concerns. That set the stage for heavier frontend tooling and, eventually, full single-page applications where the server primarily provides APIs and the frontend behaves like a true app.

Early JavaScript wasn’t hard because the language was impossible—it was hard because the browser environment was messy. DOM scripting meant juggling different event models, inconsistent element APIs, and layout quirks that changed depending on which browser your users had. Even basic tasks like “find this element and hide it when a button is clicked” could turn into a pile of conditionals and browser-specific workarounds.

Developers spent a lot of time fighting compatibility instead of building features. Selecting elements differed across browsers, attaching events wasn’t consistent, and manipulating styles could behave unexpectedly. The result: many teams avoided heavy client-side code, or pushed users toward non-JS solutions like Flash and other plugins for richer experiences.

jQuery’s big trick was straightforward: it offered a small, readable API and handled cross-browser differences behind the scenes. A single selector syntax worked almost everywhere, event handling became predictable, and common UI effects were one function call away. Instead of learning ten browser-specific rules, people learned “the jQuery way,” and shipped results quickly.

That ease mattered culturally. JavaScript became the first language many web developers learned because it was the path to visible, interactive progress. Tutorials, snippets, and plugins spread fast; you could copy a few lines and ship something that looked modern.

As browsers improved and plugins became less acceptable (security issues, mobile support gaps, and performance concerns), teams increasingly chose native web tech. jQuery helped bridge that transition: it lowered the barrier to DOM programming, and by the time the platform matured, a generation already knew JavaScript well enough to build the next wave.

For years, JavaScript’s biggest limitation wasn’t syntax or features—it was speed. Early pages could tolerate slow execution because scripts were small: validate a form, toggle a menu, add a bit of interactivity. Once developers tried to build full applications in the browser, performance became the ceiling.

V8 is Google’s JavaScript engine, created for Chrome. An “engine” is the part of the browser that reads your JavaScript and executes it. V8’s breakthrough was treating JavaScript less like a slow, interpreted scripting language and more like code that could be optimized aggressively at runtime.

In simple terms: V8 got dramatically better at turning JavaScript into machine instructions quickly, then re-optimizing hot code paths as it learned how your program behaves. That reduced lag, made animations smoother, and shortened the time between a user click and an on-screen response.

When JavaScript became faster, teams could move more logic into the browser without the experience falling apart. That changed what felt “reasonable” to build:

Performance didn’t just make existing sites nicer—it expanded the category of software the web could host.

A key dynamic kicked in:

Better engines → developers wrote more JavaScript → users spent more time in JS-heavy apps → browsers invested even more in engines.

As companies fought for browser market share, speed became a headline feature. Real-world web apps doubled as benchmarks, and every improvement encouraged developers to push further.

V8 wasn’t alone. Mozilla’s SpiderMonkey (Firefox) and Apple’s JavaScriptCore (Safari) also improved quickly, each with its own optimization strategies. The important point isn’t which engine “won”—it’s that competition made fast JavaScript a baseline expectation.

Once JavaScript executed fast enough to power demanding interfaces reliably, it stopped being “just a browser scripting language” and started to look like a platform teams could bet on.

Node.js is a runtime that lets you run JavaScript outside the browser. Instead of writing JavaScript only for buttons, forms, and page interactions, developers could use the same language to build servers, command-line tools, and background jobs.

Node.js is built around an event loop: a way of handling lots of waiting—like network requests, database queries, and file reads—without creating a separate thread for every connection.

For many web workloads, servers spend more time waiting than computing. The event loop model made it practical to handle many concurrent users with relatively simple code, especially for apps that feel “live,” where updates need to be pushed quickly and frequently.

Node.js first gained traction in places where responsiveness mattered:

Even when teams still ran core systems in other languages, Node.js often became the glue service: handling requests, orchestrating calls to other systems, or powering internal utilities.

A big shift was cultural as much as technical. When the frontend and backend both use JavaScript, teams can share validation rules, data models, and even parts of business logic. Developers spend less time context-switching between ecosystems, which helps smaller teams move faster and helps larger teams standardize how they build and review code.

npm (the Node Package Manager) is the “app store” for JavaScript code. Instead of writing everything from scratch—date handling, routing, testing, UI widgets—teams could install a package and move on. That workflow (“install, import, ship”) sped up development and made JavaScript feel bigger than a language: it became a shared toolbox.

Once Node.js made JavaScript useful outside the browser, npm gave developers a standard way to publish and reuse modules. A tiny library built for one project could suddenly benefit thousands of others. The result was compounding progress: each new package made the next project faster to build.

Open source libraries also lowered the cost of experimentation. A startup could assemble a credible product with a small team by leaning on community-maintained packages for logging, authentication helpers, build tools, and more.

Most npm packages follow semantic versioning (semver), a three-part version like 2.4.1:

2) changes can break compatibility.4) adds features in a compatible way.1) fixes bugs.Lockfiles (like package-lock.json) record the exact versions installed so everyone on the team—and your CI server—gets the same dependency set. This prevents “it works on my machine” surprises caused by small version differences.

The downside of easy installs is easy overuse. Projects can accumulate hundreds of indirect dependencies, increasing update work and supply-chain risk. Some packages become unmaintained, forcing teams to pin older versions, replace libraries, or take over maintenance themselves. The ecosystem enabled speed—but it also made dependency hygiene a real part of shipping software.

Early websites mostly stitched together pages on the server. Then Single-Page Applications (SPAs) flipped the model: the browser became the “app runtime,” fetching data and rendering UI without full page reloads.

That shift didn’t just change code—it changed responsibilities. Frontend work moved from “make this page look right” to owning routing, state, caching, accessibility, and performance budgets. Designers, backend engineers, and product teams started collaborating around components and user flows, not just templates.

As SPAs grew, ad-hoc JavaScript quickly became hard to maintain. React, Angular, and Vue helped by offering patterns for organizing UI complexity:

Different ecosystems made different tradeoffs, but the big win was shared conventions. When a new engineer joined, they could recognize the same mental model across screens and features.

SPAs sometimes struggled with first-load speed and SEO, because the browser had to download and run a lot of JavaScript before showing content.

Server-Side Rendering (SSR) and “universal” (isomorphic) apps bridged that gap: render the first view on the server for quick display and indexing, then “hydrate” in the browser to become interactive. That approach became common with frameworks like Next.js (React) and Nuxt (Vue), especially for content-heavy pages and e-commerce.

Once frontend and backend were both JavaScript-friendly, teams started sharing logic across the stack:

The result: fewer duplicated rules, faster feature delivery, and a stronger push toward “one product codebase” thinking across teams.

As JavaScript spread from “a bit of browser scripting” into mission-critical apps, teams started using the word “JavaScript” to mean a whole family of related tools: modern ECMAScript features, build pipelines, and often TypeScript.

TypeScript is still JavaScript at heart—it just adds a type system and a compiler step. That makes it easy to adopt gradually: you can start by typing a few tricky files, keep the rest as plain .js, and still ship one bundled app.

This is why many teams say they “write JavaScript” even when the codebase is mostly .ts: the runtime is JavaScript, the ecosystem is JavaScript (npm packages, browser APIs, Node.js), and TypeScript’s output is JavaScript.

When a codebase grows, the hardest part isn’t writing new features—it’s changing old ones safely. Types act like lightweight contracts:

The key benefit is confidence: teams can refactor and ship changes with fewer regressions.

Modern JavaScript evolves quickly, but not every browser or environment supports every feature immediately. Transpilation is just:

This lets teams use newer syntax without waiting for every device in the wild to catch up.

A lot of what made “modern JavaScript” feel mature are standardized features that improved structure and readability:

import/export) for clean, reusable codePut together, TypeScript plus modern ECMAScript turned JavaScript projects into something that scales: easier to maintain, easier to onboard, and less risky to change.

JavaScript didn’t become “company-wide” only because it could run in browsers and on servers. It also became the language many teams used to run the work: building, testing, releasing, and automating everyday tasks. Once that happened, JavaScript stopped being just an app language and started acting like an internal operations layer.

As frontends got more complex, teams needed repeatable builds and dependable checks. JavaScript-based tools made that feel natural because they lived in the same repo and used the same package ecosystem.

A typical setup might include:

Because these tools run on any developer machine and in CI, they reduce the “works on my laptop” problem.

In practice, this “JavaScript everywhere” toolchain is also what makes modern vibe-coding workflows possible: when UI, build, and deployment conventions are standardized, you can generate and iterate on real applications quickly. Platforms like Koder.ai lean into that reality—letting teams describe an app in chat and produce production-grade projects (commonly React on the frontend) with source code export, deployment/hosting, custom domains, and snapshots/rollback for safe iteration.

Growing companies often shift toward monorepos so multiple apps can share one set of dependencies, configs, and conventions. That makes it easier to maintain shared component libraries, internal SDKs, and design systems—without copying code between projects.

When a design system button gets an accessibility fix, every product can pick it up through a single version bump or shared package. JavaScript (and increasingly TypeScript) makes that sharing practical because the same components can power prototypes, production UI, and documentation.

Once linting, tests, and builds are standardized, they become quality gates in CI/CD pipelines: merges are blocked if checks fail, releases are automated, and team-to-team handoffs become smoother. The result is less tribal knowledge, fewer one-off processes, and a faster path from idea to shipped feature.

JavaScript runs almost everywhere now—inside containers on Kubernetes, as serverless functions, and increasingly at the edge (CDNs and edge runtimes). That flexibility is a big reason teams standardize on it: one language, many deployment options.

JavaScript is great for I/O-heavy work (APIs, web servers, event handling), but it can struggle when you push it into “heavy compute” territory.

The npm ecosystem is a strength—and a supply-chain risk. Mature teams treat dependencies like third-party vendors: pin versions, automate audits, minimize dependency count, and enforce review gates for new packages. “Fast to add” must be balanced with “safe to run.”

For startups, JavaScript reduces time-to-market: shared skills across frontend and backend, quick hiring, and straightforward deployment from serverless to containers as traffic grows. For enterprises, it offers standardization—plus a clear need for governance (dependency hygiene, build pipelines, runtime policies).

One practical pattern that’s becoming more common is to keep JavaScript/TypeScript focused on product logic and user experience, while pushing performance- or governance-sensitive parts into services built in languages like Go or Rust. That’s also why hybrid stacks are increasingly normal—for example, teams may build React frontends while running backends on Go with PostgreSQL for predictable performance and operational simplicity.

WebAssembly will keep expanding what’s practical in web and server runtimes, letting teams run near-native code alongside JavaScript. The likely future isn’t “JS replaces everything,” but JS stays the glue: coordinating services that increasingly mix TypeScript/JS with Rust/Go/Python where they fit best.

At the workflow level, the next step is often less about a new syntax feature and more about shorter feedback loops: planning, generating, reviewing, and deploying software faster without sacrificing control. That’s the niche where tools like Koder.ai fit naturally into the JavaScript-dominant world—helping teams move from idea to a working web/server/mobile app through chat, while still keeping the option to export and own the code when it’s time to harden and scale.

JavaScript is the language you write and that engines execute. ECMAScript is the standardized specification that defines the core language (syntax, types, objects, functions).

In practice: browsers and Node.js aim to implement ECMAScript, plus additional APIs (DOM in browsers, file/network APIs in Node.js).

Because the web depends on old pages continuing to work. If a browser update broke yesterday’s sites, users would blame the browser.

That’s why new features tend to be additive (new syntax and APIs) while legacy behaviors (like var and some quirky coercions) remain, even if modern code avoids them.

Ajax lets a page request data in the background and update only part of the UI—without a full page reload.

Practical impact:

jQuery provided a consistent, readable API that hid cross-browser differences in DOM selection, events, and effects.

If you’re modernizing old code, a common approach is:

V8 (Chrome’s engine) made JavaScript much faster through aggressive runtime optimization (JIT compilation and re-optimization of hot code).

For teams, the practical result was that larger, richer UIs became feasible without freezing the page—making the browser a credible application runtime, not just a document viewer.

Node.js runs JavaScript outside the browser and uses an event loop that handles many I/O operations (network, disk, databases) efficiently.

It’s a strong fit when your service mostly waits on I/O:

npm made sharing and reusing JavaScript modules trivial, which sped up development and standardized workflows.

To keep installs predictable across machines and CI:

package-lock.json or equivalent)A SPA moves routing, rendering, and UI state into the browser, fetching data via APIs rather than reloading pages.

SSR (“universal” apps) renders the first view on the server for faster initial load and better crawlability, then hydrates in the browser for interactivity.

Rule of thumb:

TypeScript adds types and a compile step but still ships JavaScript at runtime.

Teams adopt it because it improves change safety and tooling:

It’s also adoptable gradually—file by file—without rewriting everything at once.

JavaScript is excellent for I/O-heavy work, but it can struggle with sustained CPU-heavy tasks and can face GC/latency and memory pressure in long-running services.

Common practical mitigations: