Jun 05, 2025·8 min

How Programming Languages Mirror Their Era’s Needs

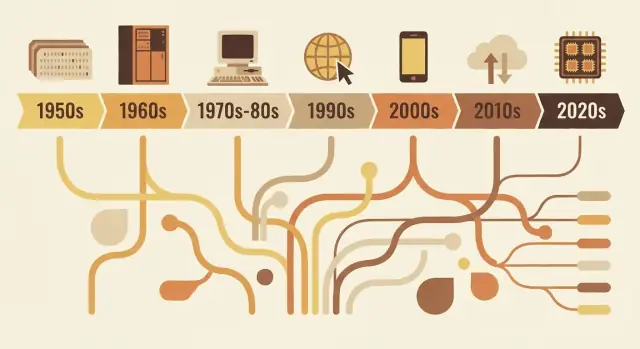

From FORTRAN to Rust, languages carry the priorities of their time: hardware limits, safety, the web, and teamwork. See how design choices map to real problems.

Why languages look the way they do

Programming languages aren’t simply “better” or “worse” versions of one another. They’re design responses to the problems people needed to solve at a particular moment in computing.

What “language design” actually includes

When we talk about language design, we’re talking about more than how code looks on the page. A language is a bundle of decisions such as:

- Syntax: how you express ideas (keywords, punctuation, readability)

- Types: whether values have declared kinds (and how strictly the language checks them)

- Memory model: who manages memory, and what safety guarantees exist

- Execution model: compiled vs interpreted, runtime behavior, performance tradeoffs

- Standard library + tooling: packages, build systems, debuggers, formatters, and how teams ship software

Those choices tend to cluster around the constraints of the era: limited hardware, expensive compute time, missing operating system features, or (later) massive teams, global networks, and security threats.

The core idea

Languages mirror their time. Early languages prioritized squeezing value out of scarce machines. Later ones prioritized portability as software had to run on many systems. As projects grew, languages leaned into structure, abstraction, and tooling to keep large codebases understandable. More recently, concurrency, cloud deployment, and security pressures have pushed new tradeoffs.

This article focuses on representative examples—not a complete, year-by-year timeline. You’ll see how a few influential languages embody the needs of their period, and how ideas get recycled and refined.

Why this matters when choosing tools today

Understanding the “why” behind a language helps you predict its strengths and blind spots. It clarifies questions like: Is this language optimized for tight performance, fast iteration, large-team maintenance, or safety? When you’re deciding what to learn or what to use on a project, that context is as practical as any feature checklist.

Early computing constraints that shaped everything

Early programming languages were shaped less by taste and more by physics and budgets. Machines had tiny amounts of memory, storage was scarce, and CPUs were slow by modern standards. That forced constant tradeoffs: every extra feature, every longer instruction, and every layer of abstraction had a real cost.

Small memory, expensive cycles

If you only have room for a small program and a small dataset, you design languages and tools that keep programs compact and predictable. Early systems pushed programmers toward simple control flow and minimal runtime support. Even “nice-to-have” features—like rich strings, dynamic memory management, or high-level data structures—could be impractical because they required extra code and bookkeeping.

Batch processing and long feedback loops

Many early programs were run in batches. You’d prepare a job (often via punch cards), submit it, and wait. If something went wrong, you might not learn why until much later—after the job finished or failed.

That long feedback cycle changed what mattered:

- Programs needed to run correctly the first time, because reruns were costly.

- Debugging was slower, so developers leaned on careful planning and conventions.

- Tooling and interactive exploration weren’t the default experience.

Why readability and error messages weren’t the priority

When machine time was precious and interfaces were limited, languages didn’t optimize for friendly diagnostics or beginner-oriented clarity. Error messages often had to be short, sometimes cryptic, and focused on helping an operator locate a problem in a deck of cards or a line of printed output.

Science and math drove early features

A large share of early computing demand came from scientific and engineering work: calculations, simulations, and numerical methods. That’s why early language features often centered on efficient arithmetic, arrays, and expressing formulas in a way that mapped well to the hardware—and to the way scientists already worked on paper.

FORTRAN, COBOL, and languages built for specific jobs

Some early programming languages weren’t trying to be universal. They were built to solve a narrow class of problems extremely well—because computers were expensive, time was scarce, and “good enough for everything” often meant “great at nothing.”

FORTRAN: numeric work, speed, and the scientist’s workload

FORTRAN (FORmula TRANslation) was aimed squarely at engineering and scientific computing. Its central promise was practical: let people write math-heavy programs without hand-coding every detail in assembly.

That goal shaped its design. It leaned into numeric operations and array-style computation, and it pushed hard on performance. The real innovation wasn’t just syntax—it was the idea that a compiler could generate machine code efficient enough that scientists would trust it. When your core job is simulations, ballistics tables, or physics calculations, shaving runtime isn’t a luxury; it’s the difference between results today or next week.

COBOL: business records, readability, and reporting

COBOL targeted a different universe: governments, banks, insurance, payroll, and inventory. These are “records and reports” problems—structured data, predictable workflows, and lots of auditing.

So COBOL favored an English-like, verbose style that made programs easier to review and maintain in large organizations. Data definitions were a first-class concern, because business software lives and dies by how well it models forms, accounts, and transactions.

What “close to the domain” really means

Both languages show a design principle that still matters: vocabulary should reflect the work.

FORTRAN speaks in math and computation. COBOL speaks in records and procedures. Their popularity reveals the priorities of their time: not abstract experimentation, but getting real workloads done efficiently—whether that meant faster numeric computation or clearer handling of business data and reporting.

The systems era: portability and control (C, Unix)

By the late 1960s and 1970s, computers were becoming cheaper and more common—but they were still wildly different from each other. If you wrote software for one machine, porting it to another often meant rewriting huge parts by hand.

Assembly pain pushed languages upward

A lot of important software was written in assembly, which gave maximum performance and control, but at a high cost: every CPU had its own instruction set, code was hard to read, and small changes could ripple into days of careful edits. That pain created demand for a language that still felt “close to the metal,” but didn’t trap you on one processor.

C’s core goal: portable systems code

C emerged as a practical compromise. It was designed to write operating systems and tools—especially Unix—while staying portable across hardware. C gave programmers:

- A straightforward, small set of features that could be compiled on many machines

- Direct access to memory through pointers

- The ability to write low-level code without switching back to assembly for every detail

Unix being rewritten in C is the famous proof point: the operating system could travel to new hardware far more easily than an assembly-only system.

Why manual memory management was acceptable

C expected you to manage memory yourself (allocate it, free it, avoid mistakes). That sounds risky now, but it matched the era’s priorities. Machines had limited resources, operating systems needed predictable performance, and programmers often worked closer to the hardware—sometimes even knowing the exact memory layout they wanted.

The lasting tradeoff

C optimized for speed and control, and it delivered. The price was safety and ease: buffer overflows, crashes, and subtle bugs became normal hazards. In that era, those risks were often considered an acceptable cost for portability and performance.

Making large programs maintainable: structure and types

As programs grew from small, single-purpose utilities into products that ran businesses, a new problem dominated: not just “can we make it work?” but “can we keep it working for years?” Early code often evolved by patching and jumping around with goto, producing “spaghetti code” that was hard to read, test, or safely change.

What structured programming tried to fix

Structured programming pushed a simple idea: code should have a clear shape. Instead of jumping to arbitrary lines, developers used well-defined building blocks—if/else, while, for, and switch—to make control flow predictable.

That predictability mattered because debugging is largely about answering “how did execution get here?” When the flow is visible in the structure, fewer bugs hide in the gaps.

The rise of teams and long-lived codebases

Once software became a team activity, maintainability became a social problem as much as a technical one. New teammates needed to understand code they didn’t write. Managers needed estimates for changes. Businesses needed confidence that updates wouldn’t break everything.

Languages responded by encouraging conventions that scale beyond one person’s memory: consistent function boundaries, clearer variable lifetimes, and ways to organize code into separate files and libraries.

Why types, modules, and scopes gained value

Types started to matter more because they serve as “built-in documentation” and early error detection. If a function expects a number but receives text, a strong type system can catch that before it reaches users.

Modules and scopes helped limit the blast radius of changes. By keeping details private and exposing only stable interfaces, teams could refactor internals without rewriting the whole program.

Design moves that supported composition

Common improvements included:

- Smaller, well-named functions that do one job

- Lexical scoping to avoid accidental interactions between variables

- Better composition patterns (passing functions/data cleanly rather than relying on global state)

Together, these changes shifted languages toward code that’s easier to read, review, and safely evolve.

Objects and enterprise: why OOP became mainstream

Go from build to deploy

Deploy and host your app without setting up a separate pipeline.

Object-oriented programming (OOP) didn’t “win” because it was the only good idea—it won because it matched what many teams were trying to build: long-lived business software maintained by lots of people.

What OOP promised

OOP offered a tidy story for complexity: represent the program as a set of “objects” with clear responsibilities.

Encapsulation (hiding internal details) sounded like a practical way to prevent accidental breakage. Inheritance and polymorphism promised reuse: write a general version once, specialize it later, and plug different implementations into the same interface.

Why GUIs and business apps pushed it forward

As desktop software and graphical interfaces took off, developers needed ways to manage many interacting components: windows, buttons, documents, menus, and events. Thinking in terms of objects and messages mapped nicely to these interactive parts.

At the same time, enterprise systems grew around domains like banking, insurance, inventory, and HR. These environments valued consistency, team collaboration, and codebases that could evolve for years. OOP fit an organizational need: divide work into modules owned by different teams, enforce boundaries, and standardize how features were added.

Where it helped—and where it got messy

OOP shines when it creates stable boundaries and reusable components. It becomes painful when developers over-model everything, creating deep class hierarchies, “god objects,” or patterns used mainly because they’re fashionable. Too many layers can make simple changes feel like paperwork.

Lasting influence

Even languages that aren’t “pure OOP” borrowed its defaults: class-like structures, interfaces, access modifiers, and design patterns. Much of modern mainstream syntax still reflects this era’s focus on organizing large teams around large codebases.

Java’s era: portability, safety, and enterprise scale

Java rose alongside a very specific kind of software boom: large, long-lived business systems spread across a messy mix of servers, operating systems, and vendor hardware. Companies wanted predictable deployments, fewer crashes, and teams that could grow without rewriting everything every few years.

What the JVM solved: portability with a managed runtime

Instead of compiling directly to a particular machine’s instructions, Java compiles to bytecode that runs on the Java Virtual Machine (JVM). That JVM became the “standard layer” enterprises could rely on: ship the same application artifact and run it on Windows, Linux, or big Unix boxes with minimal changes.

This is the core of “write once, run anywhere”: not a guarantee of zero platform quirks, but a practical way to reduce the cost and risk of supporting many environments.

Safety defaults that reduced production failures

Java made safety a primary feature rather than an optional discipline.

Garbage collection reduced a whole category of memory bugs (dangling pointers, double-frees) that were common in unmanaged environments. Array bounds checks helped prevent reading or writing memory outside a data structure. Combined with a stricter type system, these choices aimed to turn catastrophic failures into predictable exceptions—easier to reproduce, log, and fix.

Why it fit enterprise reality

Enterprises valued stability, tooling, and governance: standardized build processes, strong IDE support, extensive libraries, and a runtime that could be monitored and managed. The JVM also enabled a rich ecosystem of application servers and frameworks that made large team development more consistent.

The tradeoffs: overhead, tuning, complexity

Java’s benefits weren’t free. A managed runtime adds startup time and memory overhead, and garbage collection can create latency spikes if not tuned. Over time, the ecosystem accumulated complexity—framework layers, configuration, and deployment models—that demanded specialized knowledge.

Still, for many organizations, the bargain was worth it: fewer low-level failures, easier cross-platform deployment, and a shared runtime that scaled with the size of the business and the codebase.

Scripting languages and the push for productivity

Turn concepts into demos

Create a working demo to validate requirements with your team.

By the late 1990s and 2000s, many teams weren’t writing operating systems—they were wiring together databases, building websites, and automating internal workflows. The bottleneck shifted from raw CPU efficiency to developer time. Faster feedback and shorter release cycles made “how quickly can we change this?” a first-class requirement.

Why quick iteration became the priority

Web apps evolved in days, not years. Businesses wanted new pages, new reports, new integrations, and quick fixes without a full compile–link–deploy pipeline. Scripting languages fit that rhythm: edit a file, run it, see the result.

This also changed who could build software. System administrators, analysts, and small teams could ship useful tools without deep knowledge of memory management or build systems.

Dynamic typing and batteries-included ecosystems

Languages like Python and Ruby leaned into dynamic typing: you can express an idea with fewer declarations and less ceremony. Combined with strong standard libraries, they made common tasks feel “one import away”:

- text processing and file handling

- HTTP, email, and basic networking

- database access and data formats (CSV, JSON, XML)

That “batteries-included” approach rewarded experimentation and made automation scripts grow naturally into real applications.

Python, Ruby, and PHP as practical answers

Python became a go-to for automation and general-purpose programming, Ruby accelerated web development (especially through frameworks), and PHP dominated early server-side web because it was easy to embed directly into pages and deploy almost anywhere.

The tradeoffs: speed, runtime errors, scaling practices

The same features that made scripting languages productive also introduced costs:

- slower execution compared to compiled languages

- more errors discovered at runtime

- scaling required discipline: testing, code review, linters, and conventions

In other words, scripting languages optimized for change. Teams learned to “buy back” reliability with tooling and practices—setting the stage for modern ecosystems where developer speed and software quality are both expected.

JavaScript and the browser-driven software boom

The web browser turned into a surprise “computer” that shipped to millions of people. But it wasn’t a blank slate: it was a sandbox, it ran on unpredictable hardware, and it had to stay responsive while drawing screens and waiting on networks. That environment shaped JavaScript’s role far more than any abstract idea of a perfect language.

A platform with unusual constraints

Browsers required code to be delivered instantly, run safely next to untrusted content, and keep the page interactive. That pushed JavaScript toward quick startup, dynamic behavior, and APIs tightly tied to the page: clicks, input, timers, and later network requests.

Why “everywhere” beat “perfect”

JavaScript won largely because it was already present. If you wanted behavior in a browser, JavaScript was the default option—no install step, no permissions, no separate runtime to convince users to download. Competing ideas often looked cleaner on paper, but couldn’t match the distribution advantage of “it runs on every site.”

Event-driven by necessity

The browser is fundamentally reactive: users click, pages scroll, requests return whenever they return. JavaScript’s event-driven style (callbacks, events, promises) mirrors that reality. Instead of a program that runs start-to-finish, much of web code is “wait for something, then respond,” which fits UI and network work naturally.

Long-term effects: ecosystems and compatibility

Success created a gravity well. Huge ecosystems formed around frameworks and libraries, and the build pipeline became a product category: transpilers, bundlers, minifiers, and package managers. At the same time, the web’s promise of backward compatibility meant old decisions stuck around—so modern JavaScript often feels like layers of new tools built to live with yesterday’s constraints.

Concurrency and the multicore reality

For a long time, faster computers mostly meant one thing: your program ran faster without changing a line of code. That deal broke when chips hit heat and power limits and started adding cores instead of clock speed. Suddenly, getting more performance often required doing more than one thing at once.

Why multicore made concurrency unavoidable

Modern apps rarely perform a single, isolated task. They handle many requests, talk to databases, render UI, process files, and wait on networks—all while users expect instant responses. Multicore hardware made it possible to run work in parallel, but also made it painful when a language or runtime assumed “one main thread, one flow.”

What languages added to help

Early concurrency relied on OS threads and locks. Many languages exposed these directly, which worked—but pushed complexity onto everyday developers.

Newer designs try to make common patterns easier:

- Threads with safer primitives: better mutexes, thread pools, and clearer memory models.

- async/await: a way to write non-blocking code that still reads like normal step-by-step logic.

- Channels and message passing: “share data by communicating” (popularized by CSP-style designs) to reduce shared-state bugs.

Servers and distributed systems changed the defaults

As software moved to always-on services, the “normal” program became a server handling thousands of concurrent requests. Languages began optimizing for I/O-heavy workloads, cancellation/timeouts, and predictable performance under load.

Pitfalls languages try to prevent

Concurrency failures are often rare and hard to reproduce. Language design increasingly aims to prevent:

- Race conditions (two tasks updating the same data unpredictably)

- Deadlocks (tasks waiting on each other forever)

- Starvation (some work never gets CPU time)

The big shift: concurrency stopped being an advanced topic and became a baseline expectation.

Modern priorities: safety, simplicity, and tooling (Go, Rust)

Pick a tier that fits

Explore Koder.ai on the free tier and upgrade only if you need more.

By the 2010s, many teams weren’t struggling to express algorithms—they were struggling to keep services secure, stable, and easy to change under constant deployment pressure. Two problems stood out: security bugs caused by memory errors, and engineering drag caused by overly complex stacks and inconsistent tooling.

Fixing the bugs that keep repeating

A large share of high-severity vulnerabilities still trace back to memory safety issues: buffer overflows, use-after-free, and subtle undefined behavior that only appears in certain builds or machines. Modern language design increasingly treats these as unacceptable “foot-guns,” not just programmer mistakes.

Rust is the clearest response. Its ownership and borrowing rules are essentially a deal: you write code that satisfies strict compile-time checks, and in return you get strong guarantees about memory safety without a garbage collector. That makes Rust attractive for systems code that historically lived in C/C++—network services, embedded components, performance-critical libraries—where safety and speed both matter.

Simplicity and services as the default workload

Go takes almost the opposite approach: limit language features to keep codebases readable and predictable across large teams. Its design reflects a world of long-running services, APIs, and cloud infrastructure.

Go’s standard library and built-in concurrency primitives (goroutines, channels) support service development directly, while its fast compiler and straightforward dependency story reduce friction in day-to-day work.

Developer experience becomes a feature

Tooling moved from “optional extras” to part of the language promise. Go normalized this mindset with gofmt and a strong culture of standard formatting. Rust followed with rustfmt, clippy, and a highly integrated build tool (cargo).

In today’s “ship continuously” environment, this tooling story increasingly extends beyond compilers and linters into higher-level workflows: planning, scaffolding, and faster iteration loops. Platforms like Koder.ai reflect that shift by letting teams build web, backend, and mobile applications via a chat-driven interface—then export source code, deploy, and roll back with snapshots when needed. It’s another example of the same historical pattern: the tools that spread fastest are the ones that make the common work of the era cheaper and less error-prone.

When formatters, linters, and build systems are first-class, teams spend less time debating style or fighting inconsistent environments—and more time shipping reliable software.

What today’s problems suggest about tomorrow’s languages

Programming languages don’t “win” because they’re perfect. They win when they make the common work of the moment cheaper, safer, or faster—especially when paired with the right libraries and deployment habits.

AI, data work, and the power of ecosystems

A big driver of today’s language popularity is where the work is: data pipelines, analytics, machine learning, and automation. That’s why Python keeps growing—not just because of syntax, but because of its ecosystem: NumPy/Pandas for data, PyTorch/TensorFlow for ML, notebooks for exploration, and a huge community that produces reusable building blocks.

SQL is the quieter example of the same effect. It isn’t trendy, but it’s still the default interface to business data because it fits the job: declarative queries, predictable optimizers, and broad compatibility across tools and vendors. New languages often end up integrating SQL rather than replacing it.

Meanwhile, performance-heavy AI pushes GPU-oriented tooling forward. We’re seeing more first-class attention to vectorization, batching, and hardware acceleration—whether through CUDA ecosystems, MLIR, and compiler stacks, or languages that make it easier to bind to these runtimes.

What may shape future language designs

Several pressures are likely to influence “next era” languages and major language updates:

- Verification and correctness: stronger type systems, safer concurrency, and tools that prove properties instead of just testing.

- Privacy and policy: better support for data governance, auditability, and constraints around sensitive data.

- Energy use and efficiency: languages and runtimes that make it easier to write fast code without manual micromanagement.

Practical takeaway

When choosing a language, match it to your constraints: team experience, hiring pool, libraries you’ll rely on, deployment targets, and reliability needs. A “good” language is often the one that makes your most frequent tasks boring—and your failures easier to prevent and diagnose.

If you need a framework-based ecosystem, pick for the ecosystem; if you need correctness and control, pick for safety and performance. For a deeper decision checklist, see /blog/how-to-choose-a-programming-language.