Jul 17, 2025·8 min

How Meta-Frameworks Build on Existing Tools (Explained)

Learn how meta-frameworks sit on top of existing libraries and tools, adding routing, SSR/SSG, data loading, and build pipelines with clear trade-offs.

Learn how meta-frameworks sit on top of existing libraries and tools, adding routing, SSR/SSG, data loading, and build pipelines with clear trade-offs.

A meta-framework is a toolkit that sits on top of an existing framework (like React, Vue, or Svelte) and gives you a more complete “application starter kit.” You still write components the same way, but the meta-framework adds conventions, defaults, and extra capabilities that you’d otherwise have to assemble yourself.

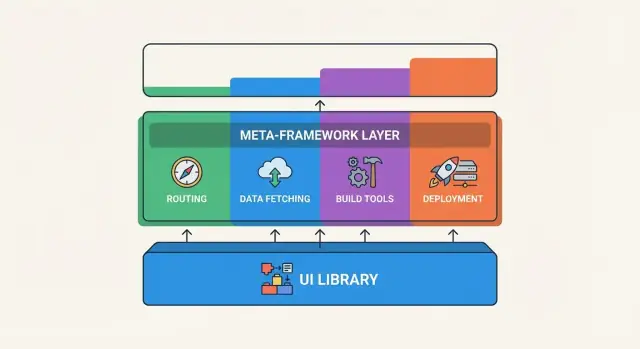

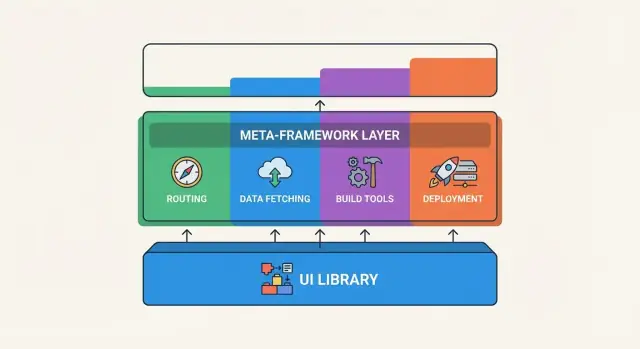

Meta-frameworks reuse the underlying framework for UI rendering, then standardize everything around it:

That’s why tools like Next.js (React), Nuxt (Vue), and SvelteKit (Svelte) feel familiar, yet opinionated.

Most meta-frameworks bundle a set of features that commonly show up in real apps:

The key point: meta-frameworks aim to turn “a UI library + a pile of decisions” into “an app you can ship.”

A meta-framework is not automatically “better” or “faster,” and it’s more than a prettier project template. It introduces its own rules and abstractions, so you’ll need to learn its mental model.

Used well, it speeds up common work and reduces decision fatigue. Used blindly, it can add complexity—especially when you fight conventions or need something outside the happy path.

A meta-framework is easiest to understand as “a framework on top of a framework.” You still write the same UI components, but you’re also opting into conventions and runtime/build features that sit above your base tools.

Think of it like a three-layer stack:

In other words: the meta-framework isn’t replacing the base framework—it’s organizing how you use it.

Most of what you already know from the underlying framework carries over.

You still build UI out of components. You can still use your preferred state patterns (local state, global stores, context, composables, etc.). The mental model of “render UI from data” remains central.

Many ecosystem choices also stay familiar: UI kits, form libraries, validation tools, and component testing often work the same way because you’re still using the same underlying framework.

The big shifts are less about individual components and more about how the project is shaped.

Project structure becomes meaningful. Instead of “put files wherever,” meta-frameworks often treat folders as configuration: where routes live, where API endpoints live, where layouts go, and how pages are grouped.

Build and runtime gain new responsibilities. A plain framework app typically compiles into client-side JavaScript. A meta-framework may also produce server code, pre-rendered HTML, or multiple builds (client + server). That changes how you think about environment variables, hosting, and performance.

Conventions start to drive behavior. File naming, special folders, and exported functions can control routing, data loading, and rendering mode. This can feel “magical” at first, but it’s usually just a consistent set of rules.

Conventions are the meta-framework’s main value-add for non-trivial apps. When routing, layouts, and data fetching follow predictable patterns, teams spend less time debating structure and more time shipping features.

That consistency helps with onboarding (“pages go here, loaders go there”), reduces one-off architecture decisions, and makes refactoring safer because the framework enforces a shared shape.

The trade-off is that you’re buying into those rules—so it’s worth learning the “layer cake” early, before your app grows and changing structure becomes expensive.

Meta-frameworks exist because building a web app isn’t just “pick a UI library and start coding.” Teams quickly run into recurring questions: How should routing work? Where does data loading live? How do you handle errors, redirects, and authentication? What’s the build and deploy story?

A meta-framework provides a default path—a set of conventions that answer big structural questions up front. That doesn’t remove flexibility, but it gives everyone a shared starting point so projects don’t become a patchwork of personal preferences.

Without conventions, teams spend time debating (and re-debating) foundational choices:

Meta-frameworks narrow the option space. Fewer choices means fewer “architecture meetings,” fewer one-off patterns, and more consistency across features.

New teammates can be productive sooner when the project follows recognizable conventions. If you’ve worked in Next.js, Nuxt, or SvelteKit before, you already know where pages live, how routes are created, and where server-side code is expected to go.

That predictability also helps in code reviews: reviewers can focus on what the feature does, not why it was implemented with a custom structure.

Meta-frameworks bundle solutions that otherwise require stitching together multiple tools—often with edge cases and maintenance overhead. Typical examples include routing, rendering options, build pipelines, environment handling, and production-friendly defaults.

The payoff is simple: teams spend more time shipping product behavior and less time assembling (and reassembling) the app’s foundations.

One of the first things a meta-framework adds on top of a UI library is a clear, opinionated way to organize pages and navigation. Plain React, Vue, or Svelte can render anything you want—but they won’t tell you where to put “the profile page” or how URLs map to components. Meta-frameworks make that mapping a default.

With file-based routing, your folder structure becomes your site structure. Create a file, get a route. Rename a folder, the URL changes. This sounds simple, but it creates a shared “obvious place” for pages that teams quickly rely on.

Nested layouts take it further: shared UI (like a header, sidebar, or account navigation) can wrap groups of routes without repeating code. Instead of manually composing layouts in every page component, you define layout boundaries once and let the router stitch things together.

Routing is also where performance decisions get baked in. Most meta-framework routers split code by route automatically, so users don’t download the whole app upfront. Visiting /pricing shouldn’t require loading your entire dashboard.

Many also standardize route-level loading states. Rather than inventing a new “loading spinner pattern” for each page, the framework provides a consistent way to show a skeleton while route data or components load, helping avoid jarring blank screens.

Real apps need the unglamorous parts of navigation: 404 pages, redirects, and dynamic URLs.

/blog/[slug]) become a standard way to express “this page depends on a URL value,” which then feeds into data loading.The routing model quietly shapes your whole application. If routes are tied to files, you’ll naturally organize features around URL boundaries. If nested layouts are encouraged, you’ll think in “sections” (marketing, app, settings) with shared shells.

These opinions can speed up development, but they also constrain you—so choose a meta-framework whose routing model matches how you want your product to evolve.

Meta-frameworks (like Next.js, Nuxt, and SvelteKit) usually give you multiple ways to render the same UI. Rendering is when and where the HTML for a page is produced.

With CSR, the browser downloads a mostly empty HTML shell plus JavaScript, then builds the page on your device. This can feel smooth after the app loads (great for app-like experiences), but the first view may be slower on weak devices or slow networks.

CSR can also be harder for search engines and link previews, because the initial HTML doesn’t contain much content.

With SSR, the server generates the HTML for each request and sends a ready-to-read page to the browser. The result: faster “first view,” better SEO, and more reliable shareable pages (social previews, crawlers, unfurl cards).

SSR often pairs with caching, so you’re not re-rendering everything for every visitor.

With static output, pages are generated ahead of time (during build) and served like simple files. This is usually the fastest and cheapest to serve, and it’s excellent for marketing pages, docs, and content that doesn’t change every second.

If you need fresher data, you can regenerate on a schedule or on demand, depending on the meta-framework.

Even if the server (SSR) or build step (SSG) sends HTML, the page may still need JavaScript to become interactive (buttons, forms, menus). Hydration is the process where the browser “wires up” that HTML to the app’s JavaScript.

Hydration improves interactivity, but it adds JavaScript work—sometimes causing delays or jank if a page is heavy.

More rendering options usually mean more complexity: you’ll think about caching rules, where code runs (server vs browser), and how much server capacity you need. SSR can increase server costs and operational overhead, while CSR shifts more work to users’ devices.

One of the biggest “meta” benefits is that data work stops being a free-for-all. Instead of each page inventing its own pattern, meta-frameworks define where data fetching happens, how updates (mutations) are handled, and when cached data should be reused or refreshed.

Most meta-frameworks let you fetch data on the server (before the page is shown), on the client (after it loads), or in a hybrid way.

Server-side loading is great for faster first paint and SEO-friendly pages. Client-side fetching is useful for highly interactive screens, like dashboards, where you expect data to refresh often without a full navigation. Hybrid patterns usually mean “get the essential data on the server, then enhance on the client.”

A common convention is splitting work into:

This structure makes forms feel less like custom plumbing and more like a feature of the framework. Instead of manually wiring a form to an API call and then figuring out how to update the UI, you follow the route’s “action” pattern, and the framework coordinates navigation, errors, and refresh.

Meta-frameworks typically cache server results so repeated visits don’t re-fetch everything. Then they provide revalidation rules to decide when cached data becomes “stale” and should be refreshed.

Revalidation can be time-based (refresh every N minutes), event-based (refresh after a successful mutation), or manual (a specific “refresh this” trigger). The goal is simple: keep pages fast without showing outdated information for too long.

Without conventions, teams often copy and paste the same fetch code across multiple pages, then forget to update one of them later.

Meta-frameworks encourage centralizing data loading at the route level (or shared utilities) so a product list, for example, is fetched the same way wherever it appears. Combined with shared caching rules, this cuts down on bugs like “page A shows old data but page B shows new data,” and makes changes easier to roll out consistently.

A meta-framework isn’t just “more features.” It also standardizes how you build and run your app. That’s why Next.js, Nuxt, and SvelteKit can feel smoother than wiring a bundler, router, SSR setup, and build scripts by hand—even when they ultimately rely on the same underlying tooling.

Most meta-frameworks either pick a bundler for you or wrap one behind a stable interface. Historically that might be Webpack; newer setups often center on Vite, or a framework-specific compiler layer.

The key idea: you interact with the meta-framework’s commands and conventions, while it translates that into bundler config. That gives you a consistent project shape (folders, entry points, build outputs), which makes examples and plugins portable across teams.

Developer experience often improves most in development:

Production builds are where the meta-framework’s “opinionated defaults” really matter. It can split code automatically, pre-render routes when possible, and generate separate server/client bundles when SSR is enabled—without you creating multiple build pipelines.

Good meta-frameworks ship with sensible defaults: file-based routing, automatic code splitting, standard linting/testing recommendations, and a predictable build output.

But real apps eventually need exceptions. Look for escape hatches like:

Abstraction can hide complexity until something breaks. When builds slow down, it can be harder to tell whether the bottleneck is your code, a plugin, the bundler, or the meta-framework’s orchestration.

A practical tip: choose a meta-framework with strong diagnostics (build analysis, clear stack traces, documented config hooks). It pays off the first time you’re chasing a production-only issue.

A meta-framework isn’t just “a nicer way to write components.” It also influences where your app runs after build—and that choice shapes performance, cost, and which features you can use.

Most meta-frameworks support multiple deployment targets, often via presets or adapters. Common options include:

The “meta” layer is the glue that packages your app appropriately for that target.

Depending on your rendering choices and hosting target, the build may produce:

This is why two apps using the same framework can deploy very differently.

Deployment usually involves two kinds of configuration:

Meta-frameworks often enforce conventions about which variables are safe to expose to the browser.

If you want SSR, you need somewhere to execute server code (Node, serverless, or edge). Static hosting can still work, but only for routes that can be pre-rendered.

Choosing a target is less about branding (“serverless” vs “edge”) and more about constraints: execution limits, streaming support, access to Node APIs, and how quickly updates roll out.

Meta-frameworks often ship with “batteries included” features that feel like shortcuts—especially around authentication, request handling, and security. These built-ins can save days of wiring, but it helps to know what they actually provide (and what they don’t).

Most meta-framework ecosystems encourage a small set of common auth approaches:

The “hook” part is usually convenience: a standard place to check the current user, redirect unauthenticated visitors, or attach auth state to the request context.

Middleware (or route “guards”) is the traffic controller. It runs before a route handler or page render and can:

/login when a user isn’t signed inBecause it’s centralized, middleware reduces duplicated checks scattered across pages.

Meta-frameworks often standardize access to request headers, cookies, and environment variables across server routes and rendering functions.

A key benefit is keeping server-only secrets (API keys, database credentials) out of browser bundles. Still, you need to understand which files/functions run on the server vs the client, and where environment variables are exposed.

Built-ins don’t replace security work. You’re still responsible for:

Meta-frameworks reduce boilerplate, but they don’t automatically make your app secure—you still define the rules.

Meta-frameworks can feel like “everything you wanted, already wired up.” That convenience is real—but it has costs that are easy to miss when you’re reading the happy-path docs.

Most meta-frameworks don’t just add features; they add a preferred way to build an app. File-based routing, special folders, naming conventions, and prescribed data-loading patterns can speed up teams once learned.

The flip side is that you’re learning the meta-framework’s mental model in addition to the underlying UI framework. Even simple questions (“Where should this request run?” “Why did this page re-render?”) can have framework-specific answers.

Your React/Vue/Svelte components often remain portable, but the “app glue” usually isn’t:

If you ever migrate, the UI code may move fairly cleanly, while the routing, rendering strategy, and data layer might need a rewrite.

Meta-frameworks evolve quickly because they track multiple moving parts: the underlying framework, the build toolchain, and runtime targets (Node, serverless, edge). That can mean frequent major releases, deprecations, and changes in “recommended” patterns.

Budget time for upgrades and keep an eye on the release notes—especially when core concepts like routing, data fetching, or build output formats change.

Abstractions can hide expensive work:

The takeaway: meta-frameworks can deliver speed, but you still need to measure, profile, and understand what’s running where.

A meta-framework is rarely “better by default.” It’s better when it removes recurring work your project is already paying for in custom code, conventions, and glue. Use the checklist below to decide quickly and justify the decision to your team.

You’ll likely benefit from Next.js, Nuxt, or SvelteKit if most of these are true:

Stay with a simpler setup (or even plain React/Vue/Svelte) if these fit:

Don’t rewrite everything. Start by introducing the meta-framework where it’s naturally isolated:

Ask and answer (in writing):

If you can’t answer #4, pause and prototype before committing.

If you’re evaluating a meta-framework mainly to reduce “setup tax,” it can help to separate product architecture decisions (routing model, SSR/SSG strategy, data-loading conventions) from implementation effort (scaffolding, wiring, and repetitive glue code).

That’s a practical place for Koder.ai: it’s a vibe-coding platform where you can prototype and iterate on full-stack applications through chat, while still landing on a conventional stack (React on the web, Go + PostgreSQL on the backend, and Flutter for mobile when needed). In other words, you can explore how meta-framework conventions affect your app structure—then export source code, deploy, and roll back via snapshots if you decide to change direction.

This doesn’t replace learning your chosen meta-framework’s conventions, but it can compress the time between “we think we want SSR + file-based routing” and “we have a working, deployed slice we can measure and review.”

A meta-framework is a layer on top of a UI framework (like React, Vue, or Svelte) that provides a more complete app structure.

You still build UI with the same component model, but the meta-framework adds conventions and features like routing, data-loading patterns, rendering modes (SSR/SSG/CSR), and build/deploy defaults.

A UI framework/library focuses mainly on rendering UI components and managing state.

A meta-framework adds the “app-level” pieces you’d otherwise assemble yourself:

Usually because you want a default, consistent way to build a real application—especially as it grows.

Meta-frameworks reduce recurring decisions about:

File-based routing means your folder/file structure creates your URL structure.

Practical implications:

This makes “where does this page go?” much less ambiguous for teams.

Nested layouts let you define a shared UI shell (header/sidebar/account nav) once and have a group of routes render inside it.

This typically improves:

They’re different answers to when and where HTML gets produced:

Meta-frameworks let you mix these per route so marketing pages can be static while app pages can be server-rendered or client-heavy.

Hydration is when the browser attaches JavaScript behavior to already-rendered HTML (from SSR or SSG) so the page becomes interactive.

It matters because it’s a common performance cost:

A practical approach is to keep initial interactive code small and avoid unnecessary client-side components on content-heavy pages.

Meta-frameworks typically standardize where data fetching and updates happen so every page isn’t a custom pattern.

Common conventions include:

This reduces copy/pasted fetch logic and makes UI updates after mutations more predictable.

Because SSR and server-side loaders need a runtime that can execute server code.

Common deployment targets:

Common trade-offs include:

A practical safeguard is to prototype one real route end-to-end (data, auth, deploy) and measure performance before migrating broadly.

Before committing, confirm your hosting supports the rendering modes you plan to use.