Apr 14, 2025·8 min

How Microframeworks Enable Flexible Custom Architectures

Learn how microframeworks let teams assemble custom architectures with clear modules, middleware, and boundaries—plus trade-offs, patterns, and pitfalls.

Learn how microframeworks let teams assemble custom architectures with clear modules, middleware, and boundaries—plus trade-offs, patterns, and pitfalls.

Microframeworks are lightweight web frameworks that focus on the essentials: receiving a request, routing it to the right handler, and returning a response. Unlike full-stack frameworks, they usually don’t bundle everything you might need (admin panels, ORM/database layers, form builders, background jobs, authentication flows). Instead, they provide a small, stable core and let you add only what your product actually requires.

A full-stack framework is like buying a fully furnished house: consistent and convenient, but harder to remodel. A microframework is closer to an empty-but-structurally-sound space: you decide the rooms, the furniture, and the utilities.

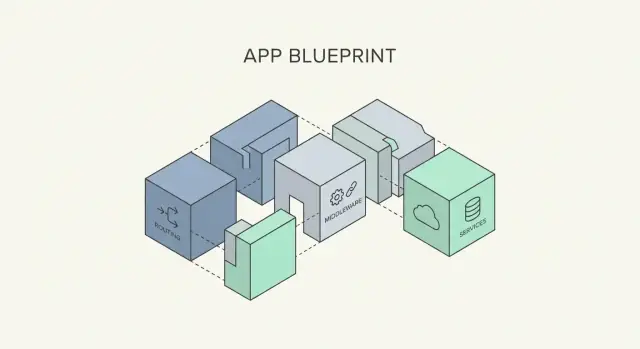

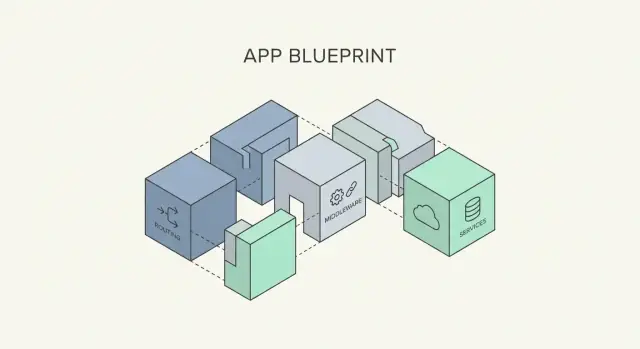

That freedom is what we mean by custom architecture—a system design shaped around your team’s needs, your domain, and your operational constraints. In plain terms: you choose the components (logging, database access, validation, auth, background processing) and decide how they connect, rather than accepting a pre-defined “one right way.”

Teams often reach for microframeworks when they want:

We’ll focus on how microframeworks support modular design: composing building blocks, using middleware, and adding dependency injection without turning the project into a science experiment.

We won’t compare specific frameworks line-by-line or claim microframeworks are always better. The goal is to help you choose structure deliberately—and evolve it safely as requirements change.

Microframeworks work best when you treat your application like a kit, not a pre-built house. Instead of accepting an opinionated stack, you start with a small core and add capabilities only when they pay for themselves.

A practical “core” is usually just:

That’s enough to ship a working API endpoint or web page. Everything else is optional until you have a concrete reason.

When you need authentication, validation, or logging, add them as separate components—ideally behind clear interfaces. This keeps your architecture understandable: each new piece should answer “what problem does this solve?” and “where does it plug in?”

Examples of “add only what you need” modules:

Early on, choose solutions that don’t trap you. Prefer thin wrappers and configuration over deep framework magic. If you can swap a module without rewriting business logic, you’re doing it right.

A simple definition of done for architecture choices: the team can explain the purpose of each module, replace it in a day or two, and test it independently.

Microframeworks stay small by design, which means you get to choose the “organs” of your application instead of inheriting a full body. This is what makes custom architecture practical: you can start minimal, then add pieces only when a real need shows up.

Most microframework-based apps begin with a router that maps URLs to controllers (or simpler request handlers). Controllers can be organized by feature (billing, accounts) or by interface (web vs. API), depending on how you want to maintain the code.

Middleware typically wraps the request/response flow and is the best place for cross-cutting concerns:

Because middleware is composable, you can apply it globally (everything needs logging) or only to specific routes (admin endpoints need stricter auth).

Microframeworks rarely force a data layer, so you can select one that matches your team and workload:

A good pattern is to keep data access behind a repository or service layer, so switching tools later doesn’t ripple through your handlers.

Not every product needs async processing on day one. When it does, add a job runner and a queue (email sending, video processing, webhooks). Treat background jobs like a separate “entry point” into your domain logic, sharing the same services as your HTTP layer rather than duplicating rules.

Middleware is where microframeworks deliver the most leverage: it lets you handle cross-cutting needs—things every request should get—without bloating each route handler. The goal is simple: keep handlers focused on business logic, and let middleware deal with the plumbing.

Instead of repeating the same checks and headers in every endpoint, add middleware once. A clean handler can then look like: parse input, call a service, return a response. Everything else—auth, logging, validation defaults, response formatting—can happen before or after.

Order is behavior. A common, readable sequence is:

If compression runs too early, it may miss errors; if error handling runs too late, you risk leaking stack traces or returning inconsistent formats.

X-Request-Id header and include it in logs.{ error, message, requestId }).Group middleware by purpose (observability, security, parsing, response shaping) and apply it at the right scope: global for truly universal rules, and route-group middleware for specific areas (e.g., /admin). Name each middleware clearly and document the expected order in a short comment near the setup so future changes don’t silently break behavior.

A microframework gives you a thin “request in, response out” core. Everything else—database access, caching, email, third‑party APIs—should be swappable. That’s where Inversion of Control (IoC) and Dependency Injection (DI) help, without turning your codebase into a science project.

If a feature needs a database, it’s tempting to create it directly inside the feature (“new database client here”). The downside: every place that “goes shopping” is now tightly tied to that specific database client.

IoC flips that: your feature asks for what it needs, and the app wiring hands it in. Your feature becomes easier to reuse and easier to change.

Dependency Injection just means passing dependencies in rather than creating them inside. In a microframework setup, this is often done at startup:

You don’t need a big DI container to get the benefits. Start with a simple rule: construct dependencies in one place, and pass them down.

To make components interchangeable, define “what you need” as a small interface, then write adapters for specific tools.

Example pattern:

UserRepository (interface): findById, create, listPostgresUserRepository (adapter): implements those methods using PostgresInMemoryUserRepository (adapter): implements the same methods for testsYour business logic only knows about UserRepository, not Postgres. Swapping storage becomes a configuration choice, not a rewrite.

The same idea works for external APIs:

PaymentsGateway interfaceStripePaymentsGateway adapterFakePaymentsGateway for local developmentMicroframeworks make it easy to accidentally scatter configuration across modules. Resist that.

A maintainable pattern is:

This gives you the main goal: swap components without rewriting the app. Changing databases, replacing an API client, or introducing a queue becomes a small change in the wiring layer—while the rest of the code stays stable.

Microframeworks don’t force a “one true way” to structure your code. Instead, they give you routing, request/response handling, and a small set of extension points—so you can adopt patterns that match your team size, product maturity, and change rate.

This is the familiar “clean and simple” setup: controllers handle HTTP concerns, services hold business rules, and repositories talk to the database.

It fits well when your domain is straightforward, your team is small to mid-size, and you want predictable places to put code. Microframeworks support it naturally: routes map to controllers, controllers call services, and repositories are wired in via lightweight manual composition.

Hexagonal architecture is useful when you expect your system to outlive today’s choices—database, message bus, third-party APIs, or even the UI.

Microframeworks work nicely here because the “adapter” layer is often your HTTP handlers plus a thin translation step into domain commands. Your ports are interfaces in the domain, and adapters implement them (SQL, REST clients, queues). The framework stays at the edge, not in the center.

If you want microservice-like clarity without operational overhead, a modular monolith is a strong option. You keep one deployable app, but split it into feature modules (e.g., Billing, Accounts, Notifications) with explicit public APIs.

Microframeworks make this easier because they don’t auto-wire everything: each module can register its own routes, dependencies, and data access, making boundaries visible and harder to accidentally cross.

Across all three patterns, the benefit is the same: you choose the rules—folder layout, dependency direction, and module boundaries—while the microframework provides a stable, small surface area to plug into.

Microframeworks make it easy to start small and stay flexible, but they don’t answer the bigger question: what “shape” should your system take? The right choice depends less on technology and more on team size, release cadence, and how painful coordination has become.

A monolith ships as one deployable unit. It’s often the fastest path to a working product: one build, one set of logs, one place to debug.

A modular monolith is still one deployable, but internally separated into clear modules (packages, bounded contexts, feature folders). This is frequently the best “next step” once the codebase grows—especially with microframeworks, where you can keep modules explicit.

Microservices split the deployable into multiple services. This can reduce coupling between teams, but it also multiplies operational work.

Split when a boundary is already real in your work:

Avoid splitting when it’s mostly convenience (“this folder is big”) or when services would share the same database tables. That’s a sign you haven’t found a stable boundary yet.

An API gateway can simplify clients (one entry point, centralized auth/rate limiting). The downside: it can become a bottleneck and a single failure point if it grows too smart.

Shared libraries speed up development (common validation, logging, SDKs), but they also create hidden coupling. If multiple services must upgrade together, you’ve recreated a distributed monolith.

Microservices add recurring costs: more deploy pipelines, versioning, service discovery, monitoring, tracing, incident response, and on-call rotations. If your team can’t comfortably run that machinery, a modular monolith built with microframework components is often the safer architecture.

A microframework gives you freedom, but maintainability is something you have to design. The goal is to make the “custom” parts easy to find, easy to replace, and hard to misuse.

Pick a structure you can explain in one minute and enforce with code review. One practical split is:

app/ (composition root: wires modules together)modules/ (business capabilities)transport/ (HTTP routing, request/response mapping)shared/ (cross-cutting utilities: config, logging, error types)tests/Keep naming consistent: module folders use nouns (billing, users), and entry points are predictable (index, routes, service).

Treat each module like a small product with clear boundaries:

modules/users/public.ts)modules/users/internal/*)Avoid “reach-through” imports like modules/orders/internal/db.ts from another module. If another part of the app needs it, promote it to the public API.

Even tiny services need basic visibility:

Put these in shared/observability so every route handler uses the same conventions.

Make errors predictable for clients and easy for humans to debug. Define one error shape (e.g., code, message, details, requestId) and one validation approach (schema per endpoint). Centralize mapping from internal exceptions to HTTP responses so handlers stay focused on business logic.

If your goal is to move fast while keeping a microframework-style architecture explicit, Koder.ai can be useful as a scaffolding and iteration tool rather than a replacement for good design. You can describe your desired module boundaries, middleware stack, and error format in chat, generate a working baseline app (for example, a React frontend with a Go + PostgreSQL backend), and then refine the wiring deliberately.

Two features map especially well to custom architecture work:

Because Koder.ai supports source code export, you can keep ownership of the architecture and evolve it in your repo the same way you would with a hand-built microframework project.

Microframework-based systems can feel “hand-assembled,” which makes testing less about a single framework’s conventions and more about protecting the seams between your pieces. The goal is confidence without turning every change into a full end-to-end run.

Start with unit tests for business rules (validation, pricing, permissions logic) because they’re fast and pinpoint failures.

Then invest in a smaller number of high-value integration tests that exercise the wiring: routing → middleware → handler → persistence boundary. These catch the subtle bugs that happen when components are combined.

Middleware is where cross-cutting behavior hides (auth, logging, rate limits). Test it like a pipeline:

For handlers, prefer testing the public HTTP shape (status codes, headers, response body) rather than internal function calls. This keeps tests stable even as internals change.

Use dependency injection (or simple constructor parameters) to swap real dependencies for fakes:

When multiple services or teams depend on an API, add contract tests that lock down request/response expectations. Provider-side contract tests ensure you don’t accidentally break consumers, even if your microframework setup and internal modules evolve.

Microframeworks give you freedom, but freedom is not automatically clarity. The main risks show up later—when the team grows, the codebase expands, and “temporary” decisions become permanent.

With fewer built-in conventions, two teams can build the same feature in two different styles (routing, error handling, response formats, logging). That inconsistency slows reviews and makes onboarding harder.

A simple guardrail helps: write a short “service template” doc (project structure, naming, error format, logging fields) and enforce it with a starter repo and a few lints.

Microframework projects often start clean, then accumulate a utils/ folder that quietly becomes a second framework. When modules share helpers, constants, and global state, boundaries blur and changes create surprise breakage.

Prefer explicit shared packages with versioning, or keep sharing minimal: types, interfaces, and well-tested primitives. If a helper depends on business rules, it likely belongs in a domain module, not “utils.”

When you’re wiring authentication, authorization, input validation, and rate limiting manually, it’s easy to miss a route, forget a middleware, or validate only “happy path” inputs.

Centralize security defaults: secure headers, consistent auth checks, and validation at the edge. Add tests that assert protected endpoints are protected.

Unplanned middleware layering adds overhead—especially if multiple middlewares parse bodies, hit storage, or serialize logs.

Keep middleware small and measurable. Document the standard order, and review new middleware for cost. If you suspect bloat, profile requests and remove redundant steps.

Microframeworks give you options—but options need a decision process. The goal isn’t to find the “best” architecture; it’s to pick a shape that your team can build, operate, and change without drama.

Before you choose “monolith” or “microservices,” answer these:

If you’re uncertain, default to a modular monolith built with a microframework. It keeps boundaries clear while staying easy to ship.

Microframeworks won’t enforce consistency for you, so choose conventions up front:

A one-page “service contract” document saved in /docs is often enough.

Start with the cross-cutting pieces you’ll need everywhere:

Treat these as shared modules, not copy-pasted snippets.

Architectures should change as requirements do. Every quarter, review where deployments are slowing down, which parts scale differently, and what breaks most often. If one domain becomes a bottleneck, that’s your candidate to split next—not the whole system.

A microframework setup rarely starts “fully designed.” It usually starts with one API, one team, and a tight deadline. The value shows up as the product grows: new features arrive, more people touch the code, and your architecture needs to stretch without snapping.

You begin with a minimal service: routing, request parsing, and one database adapter. Most logic lives close to the endpoints because it’s faster to ship.

As you add auth, payments, notifications, and reporting, you separate them into modules (folders or packages) with clear public interfaces. Each module owns its models, business rules, and data access, exposing only what other modules need.

Logging, auth checks, rate limiting, and request validation migrate into middleware so every endpoint behaves consistently. Because order matters, you should document it.

Document:

Refactor when modules start sharing too many internals, build times slow noticeably, or “small changes” require edits across multiple modules.

Consider splitting into separate services when teams are blocked by shared deployments, different parts need different scaling, or an integration boundary is already behaving like a separate product.

Microframeworks are a good fit when you want to shape the application around your domain rather than around a prescribed stack. They work especially well for teams that value clarity over convenience: you’re willing to choose (and maintain) a few key building blocks in exchange for a codebase that stays understandable as requirements change.

Your flexibility only pays off if you protect it with a few habits:

Start with two lightweight artifacts:

Finally, document decisions as you make them—even short notes help. Keep an “Architecture Decisions” page in your repo and review it periodically so yesterday’s shortcuts don’t become today’s constraints.

A microframework focuses on the essentials: routing, request/response handling, and basic extension points.

A full-stack framework typically bundles many “batteries included” features (ORM, auth, admin, forms, background jobs). Microframeworks trade convenience for control—you add only what you need and decide how pieces connect.

Microframeworks are a good fit when you want to:

A “smallest useful core” is usually:

Start there, ship one endpoint, then add modules only when they clearly pay for themselves (auth, validation, observability, queues).

Middleware is best for cross-cutting concerns that apply broadly, such as:

Keep route handlers focused on business logic: parse → call service → return response.

Order changes behavior. A common, reliable sequence is:

Document the order near setup code so future changes don’t silently break responses or security assumptions.

Inversion of Control means your business code doesn’t construct its own dependencies (it doesn’t “go shopping”). Instead, the application wiring provides what it needs.

Practically: build the database client, logger, and API clients at startup, then pass them into services/handlers. This reduces tight coupling and makes testing and swapping implementations much easier.

No. You can get most DI benefits with a simple composition root:

Add a container only if the dependency graph becomes painful to manage manually—don’t start with complexity by default.

Put storage and external APIs behind small interfaces (ports), then implement adapters:

UserRepository interface with findById, create, listPostgresUserRepository for productionA practical structure that keeps boundaries visible:

app/ composition root (wiring)modules/ feature modules (domain capabilities)transport/ HTTP routing + request/response mappingshared/ config, logging, error types, observabilityPrioritize fast unit tests for business rules, then add fewer high-value integration tests that exercise the full pipeline (routing → middleware → handler → persistence boundary).

Use DI/fakes to isolate external services, and test middleware like a pipeline (assert headers, side effects, and blocking behavior). If multiple teams depend on APIs, add contract tests to prevent breaking changes.

InMemoryUserRepository for testsHandlers/services depend on the interface, not the concrete tool. Switching databases or third-party providers becomes a wiring/config change, not a rewrite.

tests/Enforce module public APIs (e.g., modules/users/public.ts) and avoid “reach-through” imports into internals.