Dec 19, 2025·8 min

How MySQL Scaled the Early Web—and Still Runs at Huge Scale

How MySQL grew from early LAMP sites to today’s high-volume production: key design choices, InnoDB, replication, sharding, and practical scaling patterns.

How MySQL grew from early LAMP sites to today’s high-volume production: key design choices, InnoDB, replication, sharding, and practical scaling patterns.

MySQL became the early web’s go-to database for a simple reason: it matched what websites needed at the time—store and retrieve structured data quickly, run on modest hardware, and stay easy for small teams to operate.

It was approachable. You could install it fast, connect from common programming languages, and get a site working without hiring a dedicated database administrator. That blend of “good enough performance” and low operational overhead made it a default for startups, hobby projects, and growing businesses.

When people say MySQL “scaled,” they usually mean a mix of:

Early web companies didn’t just need speed; they needed predictable performance and uptime while keeping infrastructure spend under control.

MySQL’s scaling story is really a story of practical tradeoffs and repeatable patterns:

This is a tour of the patterns teams used to keep MySQL performing under real web traffic—not a full MySQL manual. The goal is to explain how the database fit the web’s needs, and why those same ideas still show up in massive production systems today.

MySQL’s breakout moment was tightly tied to the rise of shared hosting and small teams building web apps quickly. It wasn’t only that MySQL was “good enough”—it fit how the early web was deployed, managed, and paid for.

LAMP (Linux, Apache, MySQL, PHP/Perl/Python) worked because it aligned with the default server most people could afford: a single Linux box running a web server and a database side-by-side.

Hosting providers could template this setup, automate installs, and offer it cheaply. Developers could assume the same baseline environment almost everywhere, reducing surprises when moving from local development to production.

MySQL was straightforward to install, start, and connect to. It spoke familiar SQL, had a simple command-line client, and integrated cleanly with popular languages and frameworks of the time.

Just as important, the operational model was approachable: one primary process, a handful of configuration files, and clear failure modes. That made it realistic for generalist sysadmins (and often developers) to run a database without specialized training.

Being open-source removed upfront licensing friction. A student project, a hobby forum, and a small business site could all use the same database engine as larger companies.

Documentation, mailing lists, and later online tutorials created momentum: more users meant more examples, more tools, and faster troubleshooting.

Most early sites were read-heavy and fairly simple: forums, blogs, CMS-driven pages, and small e-commerce catalogs. These apps typically needed fast lookups by ID, recent posts, user accounts, and basic search or filtering—exactly the kind of workload MySQL could handle efficiently on modest hardware.

Early MySQL deployments often started as “one server, one database, one app.” That worked fine for a hobby forum or a small company site—until the app got popular. Page views turned into sessions, sessions turned into constant traffic, and the database stopped being a quiet backroom component.

Most web apps were (and still are) read-heavy. A homepage, product list, or profile page might be viewed thousands of times for every single update. That imbalance shaped early scaling decisions: if you could make reads faster—or avoid hitting the database for reads entirely—you could serve far more users without rewriting everything.

The catch: even read-heavy apps have critical writes. Sign-ups, purchases, comments, and admin updates can’t be dropped. As traffic grows, the system has to handle both a flood of reads and “must-succeed” writes at the same time.

At higher traffic, problems became visible in simple terms:

Teams learned to split responsibilities: the app handles business logic, a cache absorbs repeated reads, and the database focuses on accurate storage and essential queries. That mental model set the stage for later steps like query tuning, better indexing, and scaling out with replicas.

A unique thing about MySQL is that it’s not “one database engine” under the hood. It’s a database server that can store and retrieve data using different storage engines.

At a high level, a storage engine is the part that decides how rows are written to disk, how indexes are maintained, how locks work, and what happens after a crash. Your SQL can look identical, but the engine determines whether the database behaves more like a fast notebook—or like a bank ledger.

For a long time, many MySQL setups used MyISAM. It was simple and often quick for read-heavy sites, but it had trade-offs:

InnoDB flipped those assumptions:

As web apps shifted from mostly reading pages to handling logins, carts, payments, and messaging, correctness and recovery mattered as much as speed. InnoDB made it realistic to scale without fearing that a restart or traffic spike would corrupt data or stall the whole table.

The practical takeaway: engine choice affects both performance and safety. It’s not just a checkbox—your locking model, failure behavior, and app guarantees depend on it.

Before sharding, read replicas, or elaborate caching, many early MySQL wins came from one consistent shift: making queries predictable. Indexes and query design were the first “multiplier” because they reduced how much data MySQL had to touch per request.

Most MySQL indexes are B-tree based. Think of them as an ordered directory: MySQL can jump to the right place and read a small, contiguous slice of data. Without the right index, the server often falls back to scanning rows one by one. At low traffic that’s merely slow; at scale it becomes a traffic amplifier—more CPU, more disk I/O, more lock time, and higher latency for everything else.

A few patterns repeatedly caused “it worked in staging” failures:

SELECT *: pulls unnecessary columns, increases I/O, and can defeat covering-index benefits.WHERE name LIKE '%shoe' can’t use a normal B-tree index effectively.WHERE DATE(created_at) = '2025-01-01' often prevents index use; prefer range filters like created_at >= ... AND created_at < ....Two habits scaled better than any one clever trick:

EXPLAIN to verify you’re using the intended index and not scanning.Design indexes around how the product behaves:

(user_id, created_at) make “latest items” fast.Good indexing isn’t “more indexes.” It’s the right few that match critical read/write paths.

When a MySQL-backed product starts to slow down, the first big decision is whether to scale up (vertical) or scale out (horizontal). They solve different problems—and they change your operational life in very different ways.

Vertical scaling means giving MySQL more resources on one machine: faster CPU, more RAM, better storage.

This often works surprisingly well because many bottlenecks are local:

Vertical scaling is usually the quickest win: fewer moving parts, simpler failure modes, and less application change. The downside is there’s always a ceiling (and upgrades can require downtime or risky migrations).

Horizontal scaling adds machines. For MySQL, that typically means:

It’s harder because you introduce coordination problems: replication lag, failover behavior, consistency trade-offs, and more operational tooling. Your application also needs to know which server to talk to (or you need a proxy layer).

Most teams don’t need sharding as their first scaling step. Start by confirming where time is spent (CPU vs I/O vs lock contention), fix slow queries and indexes, and right-size memory and storage. Horizontal scaling pays off when a single machine can’t meet your write rate, storage size, or availability requirements—even after good tuning.

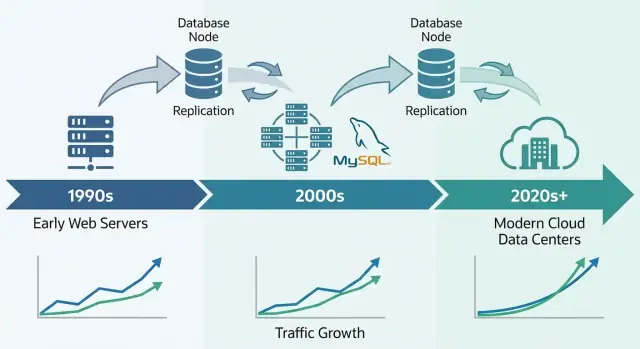

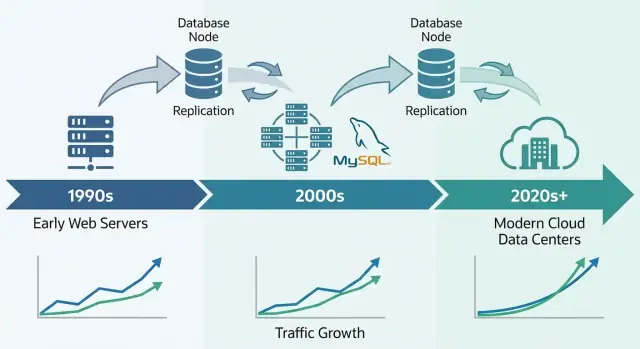

Replication is one of the most practical ways MySQL systems handled growth: instead of making one database do everything, you copy its data to other servers and spread the work.

Think of a primary (sometimes called “master”) as the database that accepts changes—INSERTs, UPDATEs, DELETEs. One or more replicas (formerly “slaves”) continuously pull those changes and apply them, keeping a near-real-time copy.

Your application can then:

This pattern became common because web traffic often grows “read-heavy” faster than it grows “write-heavy.”

Read replicas weren’t only about serving page views faster. They also helped isolate work that would otherwise slow down the main database:

Replication is not a free lunch. The most common issue is replication lag—replicas may be seconds (or more) behind the primary during spikes.

That leads to a key app-level question: read-your-writes consistency. If a user updates a profile and you immediately read from a replica, they might see the old data. Many teams solve this by reading from the primary for “fresh” views, or by using a short “read from primary after write” window.

Replication copies data; it doesn’t automatically keep you online during failures. Failover—promoting a replica, redirecting traffic, and ensuring the app reconnects safely—is a separate capability that requires tooling, testing, and clear operational procedures.

High availability (HA) is the set of practices that keep your app running when a database server crashes, a network link drops, or you need to do maintenance. The goals are simple: reduce downtime, make maintenance safe, and ensure recovery is predictable instead of improvised.

Early MySQL deployments often started with one primary database. HA typically added a second machine so failure didn’t mean a long outage.

Automation helps, but it also raises the bar: your team must trust the detection logic and prevent “split brain” (two servers thinking they’re primary).

Two metrics make HA decisions less emotional and more measurable:

HA isn’t only topology—it’s practice.

Backups must be routine, but the key is restore tests: can you actually recover to a new server, quickly, under pressure?

Schema changes also matter. Large table alterations can lock writes or slow queries. Safer approaches include running changes during low-traffic windows, using online schema change tools, and always having a rollback plan.

Done well, HA turns failures from emergencies into planned, rehearsed events.

Caching was one of the simplest ways early web teams kept MySQL responsive as traffic climbed. The idea is straightforward: serve repeated requests from something faster than the database, and only hit MySQL when you must. Done well, caching cuts read load dramatically and makes sudden spikes feel like a gentle ramp instead of a stampede.

Application/object cache stores “pieces” of data your code asks for often—user profiles, product details, permission checks. Instead of running the same SELECT hundreds of times per minute, the app reads a precomputed object by key.

Page or fragment cache stores rendered HTML (full pages or parts like a sidebar). This is especially effective for content-heavy sites where many visitors view the same pages.

Query results caching keeps the result of a specific query (or a normalized version of it). Even if you don’t cache at the SQL level, you can cache “the result of this endpoint” using a key that represents the request.

Conceptually, teams use in-memory key/value stores, HTTP caches, or built-in caching in application frameworks. The exact tool matters less than consistent keys, TTLs (expiration), and clear ownership.

Caching trades freshness for speed. Some data can be slightly stale (news pages, view counts). Other data can’t (checkout totals, permissions). You typically choose between:

If invalidation fails, users may see outdated content. If it’s too aggressive, you lose the benefit and MySQL gets hammered again.

When traffic surges, caches absorb repeat reads while MySQL focuses on “real work” (writes, cache misses, complex queries). This reduces queueing, prevents slowdowns from cascading, and buys time to scale safely.

There’s a point where “bigger hardware” and even careful query tuning stop buying you headroom. If a single MySQL server can’t keep up with write volume, dataset size, or maintenance windows, you start looking at splitting the data.

Partitioning splits one table into smaller pieces inside the same MySQL instance (for example, by date). It can make deletes, archiving, and some queries faster, but it doesn’t let you exceed the CPU, RAM, and I/O limits of that one server.

Sharding splits data across multiple MySQL servers. Each shard holds a subset of rows, and your application (or a routing layer) decides where each request goes.

Sharding usually shows up when:

A good shard key spreads traffic evenly and keeps most requests on a single shard:

Sharding trades simplicity for scale:

Start with caching and read replicas to remove pressure from the primary. Next, isolate the heaviest tables or workloads (sometimes splitting by feature or service). Only then move to sharding—ideally in a way that lets you add shards gradually rather than redesign everything at once.

Running MySQL for a busy product is less about clever features and more about disciplined operations. Most outages don’t start with a dramatic failure—they start with small signals nobody connected in time.

At scale, the “big four” signals tend to predict trouble earliest:

Good dashboards add context: traffic, error rates, connection counts, buffer pool hit rate, and top queries. The goal is to spot change—not memorize “normal.”

Many queries look fine in staging and even in production during quiet hours. Under load, the database behaves differently: caches stop helping, concurrent requests amplify lock contention, and a slightly inefficient query can trigger more reads, more temporary tables, or bigger sort work.

That’s why teams rely on the slow query log, query digests, and real production histograms rather than one-off benchmarks.

Safe change practices are boring on purpose: run migrations in small batches, add indexes with minimal locking when possible, verify with explain plans, and keep rollbacks realistic (sometimes the rollback is “stop the rollout and fail over”). Changes should be measurable: before/after latency, lock waits, and replication lag.

During an incident: confirm impact, identify the top offender (a query, a host, a table), then mitigate—throttle traffic, kill runaway queries, add a temporary index, or shift reads/writes.

Afterward, write down what happened, add alerts for the early signals, and make the fix repeatable so the same failure doesn’t return next week.

MySQL remains a default choice for many modern production systems because it matches the shape of everyday application data: lots of small reads and writes, clear transactional boundaries, and predictable queries. That’s why it still fits OLTP-heavy products like SaaS apps, e-commerce, marketplaces, and multi-tenant platforms—especially when you model data around real business entities and keep transactions focused.

Today’s MySQL ecosystem benefits from years of hard lessons baked into better defaults and safer operational habits. In practice, teams rely on:

Many companies now run MySQL through managed services, where the provider handles routine work like patching, automated backups, encryption, point-in-time recovery, and common scaling steps (bigger instances, read replicas, storage growth). You still own your schema, queries, and data access patterns—but you spend less time on maintenance windows and recovery drills.

One reason the “MySQL scaling playbook” still matters is that it’s rarely just a database problem—it’s an application architecture problem. Choices like read/write separation, cache keys and invalidation, safe migrations, and rollback plans work best when they’re designed alongside the product, not bolted on during incidents.

If you’re building new services and want to encode these decisions early, a vibe-coding workflow can help. For example, Koder.ai can take a plain-language spec (entities, traffic expectations, consistency needs) and help generate an app scaffold—typically React on the web and Go services—while keeping you in control of the data layer design. Its Planning Mode, snapshots, and rollback are especially useful when iterating on schemas and deployment changes without turning every migration into a high-risk event.

If you want to explore Koder.ai tiers (Free, Pro, Business, Enterprise), see /pricing.

Pick MySQL when you need: strong transactions, a relational model, mature tooling, predictable performance, and a large hiring pool.

Consider alternatives when you need: massive write fan-out with flexible schemas (some NoSQL systems), globally consistent multi-region writes (specialized distributed databases), or analytics-first workloads (columnar warehouses).

The practical takeaway: start from requirements (latency, consistency, data model, growth rate, team skills), then choose the simplest system that meets them—and MySQL often still does.

MySQL hit a sweet spot for early websites: quick to install, easy to connect to from common languages, and “good enough” performance on modest hardware. Combined with open-source accessibility and the LAMP stack’s ubiquity on shared hosting, it became the default database for many small teams and growing sites.

In this context, “scale” usually means handling:

It’s not just raw speed—it’s predictable performance and uptime under real workloads.

LAMP made deployment predictable: a single Linux machine could run Apache + PHP + MySQL cheaply, and hosting providers could standardize and automate it. That consistency reduced friction moving from local development to production and helped MySQL spread as a “default available” database.

Early web workloads were often read-heavy and straightforward: user accounts, recent posts, product catalogs, and simple filtering. MySQL performed well for fast lookups (often by primary key) and common patterns like “latest items,” especially when indexes matched the access patterns.

Common early pain points included:

These issues often appeared only after traffic increased, turning “minor inefficiencies” into major latency spikes.

A storage engine controls how MySQL writes data, maintains indexes, locks rows/tables, and recovers from crashes. Choosing the right engine affects both performance and correctness—two setups can run the same SQL but behave very differently under concurrency and failure.

MyISAM was common early on because it could be simple and fast for reads, but it relies heavily on table-level locks, lacks transactions, and is weaker on crash recovery. InnoDB brought row-level locking, transactions, and stronger durability—making it a better default as apps needed safer writes (logins, carts, payments) at scale.

Indexes let MySQL find rows quickly instead of scanning entire tables. Practical habits that matter:

SELECT *; fetch only needed columnsLIKE and functions on indexed columnsEXPLAIN to confirm index usageThe goal is predictable query cost under load.

Vertical scaling (“bigger box”) adds CPU/RAM/faster storage to one server—often the quickest win with fewer moving parts. Horizontal scaling (“more boxes”) adds replicas and/or shards, but introduces coordination complexity (replication lag, routing, failover behavior). Most teams should exhaust query/index fixes and right-sizing before jumping to sharding.

Read replicas help by sending many reads (and often reporting/backup workloads) to secondary servers while keeping writes on the primary. The main trade-off is replication lag, which can break “read-your-writes” expectations—so apps often read from the primary right after a write or use a short “read from primary” window.