Sep 11, 2025·8 min

How ORMs Simplify Database Access—and What They Can Cost

ORMs speed up development by hiding SQL details, but they can add slow queries, tricky debugging, and maintenance costs. Learn trade-offs and fixes.

ORMs speed up development by hiding SQL details, but they can add slow queries, tricky debugging, and maintenance costs. Learn trade-offs and fixes.

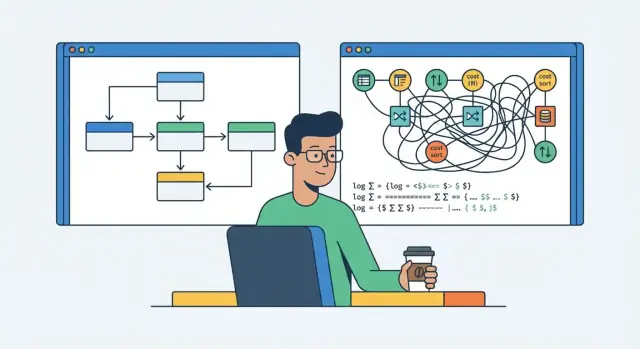

An ORM (Object–Relational Mapper) is a library that lets your application work with database data using familiar objects and methods, instead of writing SQL for every operation. You define models like User, Invoice, or Order, and the ORM translates common actions—create, read, update, delete—into SQL behind the scenes.

Applications usually think in terms of objects with nested relationships. Databases store data in tables with rows, columns, and foreign keys. That gap is the mismatch.

For example, in code you might want:

Customer objectOrdersOrder has many LineItemsIn a relational database, that’s three (or more) tables linked by IDs. Without an ORM, you often write SQL joins, map rows into objects, and keep that mapping consistent across the whole codebase. ORMs package that work into conventions and reusable patterns, so you can say “give me this customer and their orders” in the language of your framework.

ORMs can speed up development by providing:

customer.orders)An ORM reduces repetitive SQL and mapping code, but it doesn’t remove database complexity. Your app still depends on indexes, query plans, transactions, locks, and the actual SQL executed.

The hidden costs usually show up as projects grow: performance surprises (N+1 queries, over-fetching, inefficient pagination), debugging difficulty when generated SQL isn’t obvious, schema/migration overhead, transaction and concurrency gotchas, and long-term portability and maintenance trade-offs.

ORMs simplify the “plumbing” of database access by standardizing how your app reads and writes data.

The biggest win is how quickly you can perform basic create/read/update/delete actions. Instead of assembling SQL strings, binding parameters, and mapping rows back into objects, you typically:

Many teams add a repository or service layer on top of the ORM to keep data access consistent (for example, UserRepository.findActiveUsers()), which can make code reviews easier and reduce ad-hoc query patterns.

ORMs handle a lot of mechanical translation:

This reduces the amount of “row-to-object” glue code scattered across the application.

ORMs boost productivity by replacing repetitive SQL with a query API that’s easier to compose and refactor.

They also commonly bundle features teams would otherwise build themselves:

Used well, these conventions create a consistent, readable data access layer across the codebase.

ORMs feel friendly because you mostly write in your application’s language—objects, methods, and filters—while the ORM turns those instructions into SQL behind the scenes. That translation step is where a lot of convenience (and a lot of surprises) live.

Most ORMs build an internal “query plan” from your code, then compile it into SQL with parameters. For example, a chain like User.where(active: true).order(:created_at) might become a SELECT ... WHERE active = $1 ORDER BY created_at query.

The important detail: the ORM also decides how to express your intent—what tables to join, when to use subqueries, how to limit results, and whether to add extra queries for associations.

ORM query APIs are great at expressing common operations safely and consistently. Handwritten SQL gives you direct control over:

With an ORM, you’re often steering rather than driving.

For many endpoints, the ORM generates SQL that’s perfectly fine—indexes are used, result sizes are small, and latency stays low. But when a page is slow, “good enough” can stop being good.

Abstraction can hide choices that matter: a missing composite index, an unexpected full table scan, a join that multiplies rows, or an auto-generated query that fetches far more data than needed.

When performance or correctness matters, you need a way to inspect the actual SQL and the query plan. If your team treats ORM output as invisible, you’ll miss the moment where convenience quietly becomes cost.

N+1 queries usually start as “clean” code that quietly turns into a database stress test.

Imagine an admin page that lists 50 users, and for each user you show “last order date.” With an ORM, it’s tempting to write:

users = User.where(active: true).limit(50)user.orders.order(created_at: :desc).firstThat reads nicely. But behind the scenes it often becomes 1 query for users + 50 queries for orders. That’s the “N+1”: one query to get the list, then N more to fetch related data.

Lazy loading waits until you access user.orders to run a query. It’s convenient, but it hides the cost—especially inside loops.

Eager loading preloads relationships in advance (often via joins or separate IN (...) queries). It fixes N+1, but it can backfire if you preload huge graphs you don’t actually need, or if the eager load creates a massive join that duplicates rows and inflates memory.

SELECTsPrefer fixes that match what the page truly needs:

SELECT * when you only need timestamps or IDs)ORMs make it easy to “just include” related data. The catch is that the SQL required to satisfy those convenience APIs can be much heavier than you expect—especially as your object graph grows.

Many ORMs default to joining multiple tables to hydrate a full set of nested objects. That can produce wide result sets, repeated data (the same parent row duplicated across many child rows), and joins that prevent the database from using the best indexes.

A common surprise: a query that looks like “load Order with Customer and Items” can translate into several joins plus extra columns you never asked for. The SQL is valid, but the plan can be slower than a hand-tuned query that joins fewer tables or fetches relationships in a more controlled way.

Over-fetching happens when your code asks for an entity and the ORM selects all columns (and sometimes relationships) even if you only need a few fields for a list view.

Symptoms include slow pages, high memory usage in the app, and larger network payloads between the app and database. It’s especially painful when a “summary” screen quietly loads full text fields, blobs, or large related collections.

Offset-based pagination (LIMIT/OFFSET) can degrade as the offset grows, because the database may scan and discard many rows.

ORM helpers can also trigger costly COUNT(*) queries for “total pages,” sometimes with joins that make counts incorrect (duplicates) unless the query uses DISTINCT carefully.

Use explicit projections (select only needed columns), review generated SQL during code review, and prefer keyset pagination (“seek method”) for large datasets. When a query is business-critical, consider writing it explicitly (via the ORM’s query builder or raw SQL) so you control joins, columns, and pagination behavior.

ORMs make it easy to write database code without thinking in SQL—right up until something breaks. Then the error you get is often less about the database problem and more about how the ORM tried (and failed) to translate your code.

A database might say something clear like “column does not exist” or “deadlock detected,” but the ORM can wrap that into a generic exception (like QueryFailedError) tied to a repository method or model operation. If multiple features share the same model or query builder, it’s not obvious which call site produced the failing SQL.

To make it worse, a single line of ORM code can expand into multiple statements (implicit joins, separate selects for relations, “check then insert” behavior). You’re left debugging a symptom, not the actual query.

Many stack traces point to internal ORM files rather than your app code. The trace shows where the ORM noticed the failure, not where your application decided to run the query. That gap grows when lazy loading triggers queries indirectly—during serialization, template rendering, or even logging.

Enable SQL logging in development and staging so you can see the generated queries and parameters. In production, be careful:

Once you have the SQL, use the database’s query analysis tools—EXPLAIN/ANALYZE—to see whether indexes are used and where time is spent. Pair that with slow-query logs to catch problems that don’t throw errors but quietly degrade performance over time.

ORMs don’t just generate queries—they quietly influence how your database is designed and how it evolves. Those defaults can be fine early on, but they often accumulate “schema debt” that becomes expensive once the app and data grow.

Many teams accept generated migrations as-is, which can bake in questionable assumptions:

A common pattern is building “flexible” models that later need stricter rules. Tightening constraints after months of production data is harder than setting them intentionally from day one.

Migrations can drift across environments when:

The result: staging and production schemas aren’t truly identical, and failures appear only during releases.

Big schema changes can create downtime risks. Adding a column with a default, rewriting a table, or changing a data type may lock tables or run long enough to block writes. ORMs can make these changes look harmless, but the database still has to do the heavy lifting.

Treat migrations like code you’ll maintain:

ORMs often make transactions feel “handled.” A helper like withTransaction() or a framework annotation can wrap your code, auto-commit on success, and auto-roll back on errors. That convenience is real—but it also makes it easy to start transactions without noticing, keep them open too long, or assume the ORM is doing the same thing you would do in hand-written SQL.

A common misuse is putting too much work inside a transaction: API calls, file uploads, email sending, or expensive calculations. The ORM won’t stop you, and the result is a long-running transaction that holds locks longer than expected.

Long transactions increase the odds of:

Many ORMs use a unit-of-work pattern: they track changes to objects in memory and later “flush” those changes to the database. The surprise is that flushing can happen implicitly—for example, before a query runs, at commit time, or when a session is closed.

That can lead to unexpected writes:

Developers sometimes assume “I loaded it, so it won’t change.” But other transactions can update the same rows between your reads and writes unless you’ve chosen an isolation level and locking strategy that matches your needs.

Symptoms include:

Keep the convenience, but add discipline:

If you want a deeper performance-oriented checklist, see /blog/practical-orm-checklist.

Portability is one of the selling points of an ORM: write your models once, point the app at a different database later. In practice, many teams discover a quieter reality—lock-in—where important pieces of your data access are tied to one ORM and often one database.

Vendor lock-in isn’t only about your cloud provider. With ORMs, it usually means:

Even if the ORM supports multiple databases, you may have written to the “common subset” for years—then discover the ORM’s abstractions don’t map cleanly to the new engine.

Databases differ for a reason: they offer features that can make queries simpler, faster, or safer. ORMs often struggle to expose these well.

Common examples:

If you avoid these features to stay “portable,” you might end up writing more application code, running more queries, or accepting slower SQL performance. If you embrace them, you may step outside the ORM’s comfortable path and lose the easy portability you expected.

Treat portability as a goal, not a constraint that blocks good database design.

A practical compromise is to standardize on the ORM for everyday CRUD, but allow escape hatches for the places where it matters:

This keeps ORM convenience for most work while letting you leverage database strengths without rewriting your whole codebase later.

ORMs speed up delivery, but they can also postpone important database skills. That delay is a hidden cost: the bill arrives later, usually when traffic grows, data volume spikes, or an incident forces people to look “under the hood.”

When a team relies heavily on ORM defaults, some fundamentals get less practice:

These aren’t “advanced” topics—they’re basic operational hygiene. But ORMs make it possible to ship features without touching them for a long time.

Knowledge gaps usually surface in predictable ways:

Over time, this can turn database work into a specialist bottleneck: one or two people become the only ones comfortable diagnosing query performance and schema issues.

You don’t need everyone to be a DBA. A small baseline goes a long way:

Add one simple process: periodic query reviews (monthly or per release). Pick the top slow queries from monitoring, review the generated SQL, and agree on a performance budget (for example, “this endpoint must stay under X ms at Y rows”). That keeps ORM convenience—without letting the database become a black box.

ORMs aren’t all-or-nothing. If you’re feeling the costs—mysterious performance issues, hard-to-control SQL, or migration friction—you have several options that keep productivity while restoring control.

Query builders (a fluent API that generates SQL) are a good fit when you want safe parameterization and composable queries, but still need to reason about joins, filters, and indexes. They often shine for reporting endpoints and admin search pages where query shapes vary.

Lightweight mappers (sometimes called micro-ORMs) map rows to objects without trying to manage relationships, lazy loading, or unit-of-work magic. They’re a strong choice for read-heavy services, analytics-style queries, and batch jobs where you want predictable SQL and fewer surprises.

Stored procedures can help when you need strict control over execution plans, permissions, or multi-step operations close to the data. They’re commonly used for high-throughput batch processing or complex reporting shared across multiple apps—but they can increase coupling to a specific database and require strong review/testing practices.

Raw SQL is the escape hatch for the hardest cases: complex joins, window functions, recursive queries, and performance-sensitive paths.

A common middle ground: use the ORM for straightforward CRUD and lifecycle management, but switch to a query builder or raw SQL for complex reads. Treat those SQL-heavy parts as “named queries” with tests and clear ownership.

This same principle applies when you build faster with AI-assisted tooling: for example, if you generate an app on Koder.ai (React on the web, Go + PostgreSQL on the backend, Flutter for mobile), you still want clear “escape hatches” for database hot paths. Koder.ai can speed up scaffolding and iteration via chat (including planning mode and source code export), but the operational discipline remains the same: inspect the SQL your ORM emits, keep migrations reviewable, and treat performance-critical queries as first-class code.

Choose based on performance requirements (latency/throughput), query complexity, how often query shapes change, your team’s SQL comfort, and operational needs like migrations, observability, and on-call debugging.

ORMs are worth using when you treat them like a power tool: fast for common work, risky when you stop watching the blade. The goal isn’t to abandon the ORM—it’s to add a few habits that keep performance and correctness visible.

Write a short team doc and enforce it in reviews:

Add a small set of integration tests that:

Keep the ORM for productivity, consistency, and safer defaults—but treat SQL as a first-class output. When you measure queries, set guardrails, and test the hot paths, you get the convenience without paying the hidden bill later.

If you’re experimenting with rapid delivery—whether in a traditional codebase or in a vibe-coding workflow like Koder.ai—this checklist stays the same: shipping faster is great, but only if you keep the database observable and the ORM’s SQL understandable.

An ORM (Object–Relational Mapper) lets you read and write database rows using application-level models (e.g., User, Order) instead of hand-writing SQL for every operation. It translates actions like create/read/update/delete into SQL, and maps results back into objects.

It reduces repetitive work by standardizing common patterns:

customer.orders)This can make development faster and codebases more consistent across a team.

The “object vs. table mismatch” is the gap between how applications model data (nested objects and references) and how relational databases store it (tables connected by foreign keys). Without an ORM you often write joins and then manually map rows into nested structures; ORMs package that mapping into conventions and reusable patterns.

Not automatically. ORMs usually provide safe parameter binding, which helps prevent SQL injection when used correctly. Risk returns if you concatenate raw SQL strings, interpolate user input into fragments (like ORDER BY), or misuse “raw” escape hatches without proper parameterization.

Because the SQL is generated indirectly. A single line of ORM code can expand into multiple queries (implicit joins, lazy-loaded selects, auto-flush writes). When something is slow or incorrect, you need to inspect the generated SQL and the database’s execution plan rather than relying on the ORM abstraction alone.

N+1 happens when you run 1 query to fetch a list, then N more queries (often inside a loop) to fetch related data per item.

Fixes that usually work:

SELECT * for list views)Eager loading can create huge joins or preload large object graphs you don’t need, which can:

A good rule: preload the minimum relationships needed for that screen, and consider separate targeted queries for large collections.

Common issues include:

LIMIT/OFFSET pagination as offsets growCOUNT(*) queries (especially with joins and duplicates)Mitigations:

Enable SQL logging in development/staging so you can see actual queries and parameters. In production, prefer safer observability:

Then use EXPLAIN/ANALYZE to confirm index usage and find where time is spent.

The ORM can make schema changes look “small,” but the database may still lock tables or rewrite data for operations like type changes or adding defaults. To reduce risk: