Oct 04, 2025·8 min

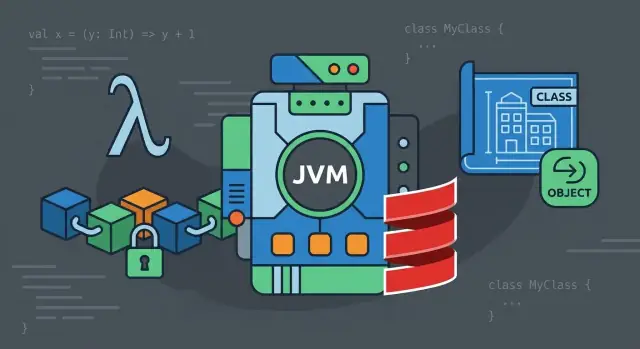

How Scala Blended Functional and OO Programming on the JVM

Explore why Scala was designed to unite functional and object-oriented ideas on the JVM, what it got right, and the trade-offs teams should know.

The Problem Scala Set Out to Solve

Java made the JVM successful, but it also set expectations that many teams eventually ran into: lots of boilerplate, a heavy emphasis on mutable state, and patterns that often required frameworks or code generation to stay manageable. Developers liked the JVM’s speed, tooling, and deployment story—but they wanted a language that let them express ideas more directly.

What developers wanted beyond “classic Java”

By the early 2000s, everyday JVM work involved verbose class hierarchies, getter/setter ceremony, and null-related bugs that slipped into production. Writing concurrent programs was possible, but shared mutable state made subtle race conditions easy to create. Even when teams followed good object-oriented design, the day-to-day code still carried a lot of accidental complexity.

Scala’s bet was that a better language could reduce that friction without abandoning the JVM: keep performance “good enough” by compiling to bytecode, but give developers features that help them model domains cleanly and build systems that are easier to change.

Why mixing FP and OOP mattered in real projects

Most JVM teams weren’t choosing between “pure functional” and “pure object-oriented” styles—they were trying to ship software under deadlines. Scala aimed to let you use OO where it fits (encapsulation, modular APIs, service boundaries) while leaning on functional ideas (immutability, expression-oriented code, composable transformations) to make programs safer and easier to reason about.

That blend mirrors how real systems are often built: object-oriented boundaries around modules and services, with functional techniques inside those modules to reduce bugs and simplify testing.

The goals: safer code, reuse, JVM practicality

Scala set out to provide stronger static typing, better composition and reuse, and language-level tools that reduce boilerplate—all while staying compatible with JVM libraries and operations.

A quick history note

Martin Odersky designed Scala after working on Java’s generics and seeing strengths in languages like ML, Haskell, and Smalltalk. The community that formed around Scala—academia, enterprise JVM teams, and later data engineering—helped shape it into a language that tries to balance theory with production needs.

Scala’s “Everything Is an Object” Core

Scala takes the phrase “everything is an object” seriously. Values you might think of as “primitive” in other JVM languages—like 1, true, or 'a'—behave like normal objects with methods. That means you can write code like 1.toString or 'a'.isLetter without switching mental modes between “primitive operations” and “object operations”.

Why this feels familiar to Java developers

If you’re used to Java-style modeling, Scala’s object-oriented surface area is immediately recognizable: you define classes, create instances, call methods, and group behavior with interface-like types.

You can model a domain in a straightforward way:

class User(val name: String) {

def greet(): String = s"Hi, $name"

}

val u = new User("Sam")

println(u.greet())

That familiarity matters on the JVM: teams can adopt Scala without giving up the basic “objects with methods” way of thinking.

Where Scala’s OO differs from Java (practical differences)

Scala’s object model is more uniform and flexible than Java’s:

- Singleton objects are first-class (

object Config { ... }), which often replaces Java’sstaticpatterns. - Methods are expression-friendly: return values are emphasized, and many “statements” are written as value-producing expressions.

- Constructors and fields are tighter: constructor parameters can become fields with

val/var, reducing boilerplate.

Inheritance still exists and is commonly used, but it’s often lighter-weight:

class Admin(name: String) extends User(name) {

override def greet(): String = s"Welcome, $name"

}

In day-to-day work, this means Scala supports the same OO building blocks people rely on—classes, encapsulation, overriding—while smoothing over some JVM-era awkwardness (like heavy static usage and verbose getters/setters).

Functional Basics in Scala: Immutability and Expressions

Scala’s functional side isn’t a separate “mode”—it shows up in the everyday defaults the language nudges you toward. Two ideas drive most of it: prefer immutable data, and treat your code as expressions that produce values.

Immutability as a default mindset (vals vs vars)

In Scala, you declare values with val and variables with var. Both exist, but the cultural default is val.

When you use val, you’re saying: “this reference won’t be reassigned.” That small choice reduces the amount of hidden state in your program. Less state means fewer surprises when code grows, especially in multi-step business workflows where values get transformed repeatedly.

var still has a place—UI glue code, counters, or performance-critical sections—but reaching for it should feel intentional rather than automatic.

Expressions that return values (less step-by-step state)

Scala encourages writing code as expressions that evaluate to a result, rather than sequences of statements that mostly mutate state.

That often looks like building a result from smaller results:

val discounted =

if (isVip) price * 0.9

else price

Here, if is an expression, so it returns a value. This style makes it easier to follow “what is this value?” without tracing a trail of assignments.

Higher-order functions in everyday code (map/filter)

Instead of loops that modify collections, Scala code typically transforms data:

val emails = users

.filter(_.isActive)

.map(_.email)

filter and map are higher-order functions: they take other functions as inputs. The benefit isn’t academic—it’s clarity. You can read the pipeline as a small story: keep active users, then extract emails.

Why pure functions help testing and reasoning

A pure function depends only on its inputs and has no side effects (no hidden writes, no I/O). When more of your code is pure, testing becomes straightforward: you pass inputs, you assert outputs. Reasoning becomes simpler too, because you don’t need to guess what else changed elsewhere in the system.

Traits and Mixins: Reusable OO Without Deep Hierarchies

Scala’s answer to “how do we share behavior without building a giant class family tree?” is the trait. A trait looks a bit like an interface, but it can also carry real implementation—methods, fields, and small helper logic.

What traits are (and why Scala leans on them)

Traits let you describe a capability (“can log”, “can validate”, “can cache”) and then attach that capability to many different classes. This encourages small, focused building blocks instead of a few oversized base classes that everyone must inherit.

Unlike single-inheritance class hierarchies, traits are designed for multiple inheritance of behavior in a controlled way. You can add more than one trait to a class, and Scala defines a clear linearization order for how methods are resolved.

Mixins: composition over class trees

When you “mix in” traits, you’re composing behavior at the class boundary rather than drilling deeper into inheritance. That’s often easier to maintain:

- You can reuse features across unrelated types.

- You can keep each trait narrow and testable.

- You can evolve behavior by adding/removing a mixin instead of refactoring a hierarchy.

A simple example:

trait Timestamped { def now(): Long = System.currentTimeMillis() }

trait ConsoleLogging { def log(msg: String): Unit = println(msg) }

class Service extends Timestamped with ConsoleLogging {

def handle(): Unit = log(s"Handled at ${now()}")

}

Traits vs abstract classes: practical guidance

Use traits when:

- You want to share a “capability” across many classes.

- You expect multiple combinations of behaviors.

- You don’t need constructor parameters (Scala 2 limitation; Scala 3 supports more flexibility).

Use an abstract class when:

- You need constructor arguments or internal state that must be initialized in one place.

- You’re modeling a tight “is-a” relationship with a small, stable hierarchy.

The real win is that Scala makes reuse feel more like assembling parts than inheriting destiny.

Pattern Matching and Algebraic Data Types (ADTs)

Speed up team alignment

Use Koder.ai as a fast loop for architecture discussions and team onboarding examples.

Scala’s pattern matching is one of the features that makes the language feel strongly “functional,” even though it still supports classic object-oriented design. Instead of pushing logic into a web of virtual methods, you can inspect a value and choose behavior based on its shape.

What pattern matching is (and why it feels functional)

At its simplest, pattern matching is a more powerful switch: it can match on constants, types, nested structures, and even bind parts of a value to names. Because it’s an expression, it naturally produces a result—often leading to compact, readable code.

sealed trait Payment

case class Card(last4: String) extends Payment

case object Cash extends Payment

def describe(p: Payment): String = p match {

case Card(last4) => s"Card ending $last4"

case Cash => "Cash"

}

Modeling data with sealed traits and case classes

That example also shows an Algebraic Data Type (ADT) in Scala style:

- A

sealed traitdefines a closed set of possibilities. case classandcase objectdefine the concrete variants.

“Sealed” is the key: the compiler knows all valid subtypes (within the same file), which unlocks safer pattern matching.

Making invalid states harder to represent

ADTs encourage you to model the real states of your domain. Instead of using null, magic strings, or booleans that can be combined in impossible ways, you define the allowed cases explicitly. That makes many errors impossible to express in code—so they can’t slip into production.

Readability benefits (and where it can be overused)

Pattern matching shines when you’re:

- decoding inputs (e.g., parsing results into success/failure cases),

- handling different message types in workflows,

- translating “a value can be one of these” into “do the right thing for each case.”

It can be overused when every behavior is expressed as giant match blocks scattered across the codebase. If matches grow large or show up everywhere, it’s often a sign you need better factoring (helper functions) or to move some behavior closer to the data type itself.

The Type System: Safety, Inference, and Complexity

Scala’s type system is one of the biggest reasons teams choose it—and one of the biggest reasons some teams bounce off it. At its best, it lets you write concise code that still gets strong compile-time checks. At its worst, it can feel like you’re debugging the compiler.

What type inference buys you

Type inference means you usually don’t have to spell out types everywhere. The compiler can often figure them out from context.

That translates to less boilerplate: you can focus on what a value represents rather than constantly annotating its type. When you do add type annotations, it’s typically to clarify intent at boundaries (public APIs, tricky generics) rather than for every local variable.

Generics and variance, in plain language

Generics let you write containers and utilities that work for many types (like List[Int] and List[String]). Variance is about whether a generic type can be substituted when its type parameter changes.

- Covariance (

+A) roughly means “a list of cats can be used where a list of animals is expected.” - Contravariance (

-A) roughly means “a handler of animals can be used where a handler of cats is expected.”

This is powerful for library design, but it can be confusing when you first meet it.

Type classes via implicits (Scala 2) and givens (Scala 3)

Scala popularized a pattern where you can “add behavior” to types without modifying them, by passing capabilities implicitly. For example, you can define how to compare or print a type and have that logic selected automatically.

In Scala 2 this uses implicit; in Scala 3 it’s expressed more directly with given/using. The idea is the same: extend behavior in a composable way.

The downside: errors and “too clever” types

The trade-off is complexity. Type-level tricks can produce long error messages, and over-abstracted code can be hard to read for newcomers. Many teams adopt a rule of thumb: use the type system to simplify APIs and prevent mistakes, but avoid designs that require everyone to think like a compiler to make a change.

Common Concurrency Tools in Scala

Scala has multiple “lanes” for writing concurrent code. That’s useful—because not every problem needs the same level of machinery—but it also means teams should be intentional about what they adopt.

Futures: the everyday default

For many JVM apps, Future is the simplest way to run work concurrently and compose results. You kick off work, then use map/flatMap to build an async workflow without blocking a thread.

A good mental model: Futures are great for independent tasks (API calls, database queries, background calculations) where you want to combine results and handle failures in one place.

Async workflows: readable composition

Scala lets you express Future chains in a more linear style (via for-comprehensions). This doesn’t add new concurrency primitives, but it makes the intent clearer and reduces “callback nesting.”

The trade-off: it’s still easy to accidentally block (e.g., waiting on a Future) or to overload an execution context if you don’t separate CPU-bound and IO-bound work.

Streaming: concurrency with backpressure

For long-running pipelines—events, logs, data processing—streaming libraries (such as Akka/Pekko Streams, FS2, or similar) focus on flow control. The key feature is backpressure: producers slow down when consumers can’t keep up.

This model often beats “just spawn more Futures” because it treats throughput and memory as first-class concerns.

Actor-style concurrency: message passing

Actor libraries (Akka/Pekko) model concurrency as independent components that communicate via messages. This can simplify reasoning about state, because each actor handles one message at a time.

Actors shine when you need long-lived, stateful processes (devices, sessions, coordinators). They can be overkill for simple request/response apps.

Why immutability helps no matter what

Immutable data structures reduce shared mutable state—the source of many race conditions. Even when you use threads, Futures, or actors, passing immutable values makes concurrency bugs rarer and debugging less painful.

Choosing the right level

Start with Futures for straightforward parallel work. Move to streaming when you need controlled throughput, and consider actors when state and coordination dominate the design.

Working with Java: Interop, Libraries, and JVM Reality

Experiment without fear

Try alternatives safely with snapshots and rollback when an experiment goes sideways.

Scala’s biggest practical advantage is that it lives on the JVM and can use the Java ecosystem directly. You can instantiate Java classes, implement Java interfaces, and call Java methods with little ceremony—often it feels like you’re just using another Scala library.

Calling Java libraries from Scala: what’s easy

Most “happy path” interop is straightforward:

- Use existing Java libraries (database drivers, HTTP clients, logging) without waiting for Scala-specific versions.

- Implement Java interfaces in Scala (common for frameworks like servlet APIs or Kafka callbacks).

- Share build tooling and deployment practices with other JVM services.

Under the hood, Scala compiles to JVM bytecode. Operationally, it runs like other JVM languages: it’s managed by the same runtime, uses the same GC, and is profiled/monitored with familiar tools.

Where interop gets awkward

The friction shows up where Scala’s defaults don’t match Java’s:

Nulls. Many Java APIs return null; Scala code prefers Option. You’ll often wrap Java results defensively to avoid surprise NullPointerExceptions.

Checked exceptions. Scala doesn’t force you to declare or catch checked exceptions, but Java libraries may throw them anyway. This can make error handling feel inconsistent unless you standardize how exceptions are translated.

Mutability. Java collections and “setter-heavy” APIs encourage mutation. In Scala, mixing mutable and immutable styles can lead to confusing code, especially at API boundaries.

Tips for mixed Scala/Java codebases

Treat the boundary as a translation layer:

- Convert nulls to

Optionimmediately, and convertOptionback to null only at the edge. - Map Java collections to the Scala collection types your team uses consistently.

- Wrap Java exceptions into domain errors (or a single error model) so callers aren’t dealing with unpredictable failure modes.

- Keep public APIs simple: prefer Java-friendly method signatures for modules meant to be consumed by Java, and Scala-idiomatic APIs for internal Scala modules.

Done well, interop lets Scala teams move faster by reusing proven JVM libraries while keeping Scala code expressive and safer inside the service.

The Trade-offs Teams Actually Feel

Scala’s pitch is attractive: you can write elegant functional code, keep OO structure where it helps, and stay on the JVM. In practice, teams don’t just “get Scala”—they feel a set of day-to-day trade-offs that show up in onboarding, builds, and code reviews.

A steeper learning curve (because there are many valid styles)

Scala gives you a lot of expressive power: multiple ways to model data, multiple ways to abstract behavior, multiple ways to structure APIs. That flexibility is productive once you share a mental model—but early on it can slow teams down.

Newcomers may struggle less with syntax and more with choice: “Should this be a case class, a regular class, or an ADT?” “Do we use inheritance, traits, type classes, or just functions?” The hard part isn’t that Scala is impossible—it’s agreeing on what your team considers “normal Scala.”

Compile times and build complexity are real costs

Scala compilation tends to be heavier than many teams expect, especially as projects grow or rely on macro-heavy libraries (more common in Scala 2). Incremental builds can help, but compile time is still a recurring practical concern: slower CI, slower feedback loops, and more pressure to keep modules small and dependencies tidy.

Build tools add another layer. Whether you use sbt or another build system, you’ll want to pay attention to caching, parallelism, and how your project is split into submodules. These aren’t academic issues—they affect developer happiness and how quickly bugs get fixed.

Tooling and IDE support: evaluate before you commit

Scala tooling has improved a lot, but it’s still worth testing with your exact stack. Before standardizing, teams should evaluate:

- IDE performance on your codebase size (indexing speed, navigation, refactors)

- Reliability of autocomplete and type hints (critical with advanced types)

- Debugger experience in typical workflows

- CI stability (especially around dependency resolution and caching)

If the IDE struggles, the language’s expressiveness can backfire: code that’s “correct” but hard to explore becomes expensive to maintain.

Style consistency isn’t optional

Because Scala supports functional programming and object-oriented programming (plus many hybrids), teams can end up with a codebase that feels like several languages at once. That’s usually where frustration starts: not from Scala itself, but from inconsistent conventions.

Conventions and linters matter because they reduce debate. Decide upfront what “good Scala” means for your team—how you handle immutability, error handling, naming, and when to reach for advanced type-level patterns. Consistency makes onboarding smoother and keeps reviews focused on behavior rather than aesthetics.

Scala 2 vs Scala 3: What Changed and Why It Matters

Visualize the workflows

Create an admin UI in React to explore workflows before you harden backend services.

Scala 3 (often called “Dotty” during development) isn’t a rewrite of Scala’s identity—it’s an attempt to keep the same FP/OOP blend while smoothing sharp edges that teams hit in Scala 2.

Syntax and philosophy: smaller “surface area”

Scala 3 keeps familiar basics, but nudges code toward clearer structure.

You’ll notice optional braces with significant indentation, which makes everyday code read more like a modern language and less like a dense DSL. It also standardizes a few patterns that were “possible but messy” in Scala 2—like adding methods via extension rather than a grab bag of implicit tricks.

Philosophically, Scala 3 tries to make powerful features feel more explicit, so readers can tell what’s happening without memorizing a dozen conventions.

Why implicits and enums changed

Scala 2’s implicits were extremely flexible: great for typeclasses and dependency injection, but also a source of confusing compilation errors and “action at a distance.”

Scala 3 replaces most implicit usage with given/using. The capability is similar, but the intent is clearer: “here is a provided instance” (given) and “this method needs one” (using). That improves readability and makes FP-style typeclass patterns easier to follow.

Enums are also a big deal. Many Scala 2 teams used sealed traits + case objects/classes to model ADTs. Scala 3’s enum gives you that pattern with a dedicated, tidy syntax—less boilerplate, same modeling power.

Migration: what teams actually do

Most real projects migrate by cross-building (publishing Scala 2 and Scala 3 artifacts) and moving module-by-module.

Tools help, but it’s still work: source incompatibilities (especially around implicits), macro-heavy libraries, and build tooling can slow you down. The good news is that typical business code ports more cleanly than code that leans hard on compiler magic.

How Scala 3 shifts the FP/OOP balance

In daily code, Scala 3 tends to make FP patterns feel more “first-class”: clearer typeclass wiring, cleaner ADTs with enums, and stronger typing tools (like union/intersection types) without as much ceremony.

At the same time, it doesn’t abandon OO—traits, classes, and mixin composition remain central. The difference is that Scala 3 makes the boundary between “OO structure” and “FP abstraction” easier to see, which usually helps teams keep codebases consistent over time.

When Scala Is a Good Fit (and When It Isn’t)

Scala can be a great “power tool” language on the JVM—but it’s not a universal default. The biggest wins show up when the problem benefits from stronger modeling and safer composition, and when the team is ready to use the language deliberately.

Good fits

Data-heavy systems and pipelines. If you’re transforming, validating, and enriching lots of data (streams, ETL jobs, event processing), Scala’s functional style and strong types help keep those transformations explicit and less error-prone.

Complex domain modeling. When business rules are nuanced—pricing, risk, eligibility, permissions—Scala’s ability to express constraints in types and build small, composable pieces can reduce “if-else sprawl” and make invalid states harder to represent.

Organizations invested in the JVM. If your world already depends on Java libraries, JVM tooling, and operational practices, Scala can deliver FP-style ergonomics without leaving that ecosystem.

Team readiness: what matters more than the language

Scala rewards consistency. Teams usually succeed when they have:

- Some familiarity with functional concepts (immutability, pure-ish functions, composition)

- A code review culture that enforces readability over cleverness

- Shared style guides and agreed defaults (how to model errors, how to structure modules, when to use advanced types)

Without these, codebases can drift into a mix of styles that’s hard for newcomers to follow.

When to avoid Scala

Small teams needing fast onboarding. If you expect frequent handoffs, many junior contributors, or rapid staffing changes, the learning curve and variety of idioms can slow you down.

Simple CRUD-only apps. For straightforward “request in / record out” services with minimal domain complexity, Scala’s benefits may not offset its build tooling, compilation time, and style decisions.

A simple decision checklist

Ask:

- Are we modeling tricky rules or doing heavy transformations?

- Will we benefit from stronger compile-time guarantees?

- Do we already rely on JVM libraries and operations?

- Can we commit to a clear style guide and disciplined reviews?

- Is the team comfortable learning (and limiting) Scala’s more advanced features?

If you answered “yes” to most of these, Scala is often a strong fit. If not, a simpler JVM language may deliver results faster.

One practical tip when you’re evaluating languages: keep a prototype loop short. For example, teams sometimes use a vibe-coding platform like Koder.ai to spin up a small reference app (API + database + UI) from a chat-based spec, iterate in planning mode, and use snapshots/rollback to explore alternatives quickly. Even if your production target is Scala, having a fast prototype you can export as source code and compare against JVM implementations can make the “should we choose Scala?” conversation more concrete—based on workflows, deployment, and maintainability rather than only language features.

FAQ

What problem was Scala originally trying to solve on the JVM?

Scala was designed to reduce common JVM pain points—boilerplate, null-related bugs, and brittle inheritance-heavy designs—while keeping JVM performance, tooling, and library access. The goal was to express domain logic more directly without leaving the Java ecosystem.

How does mixing functional programming and OOP help in real Scala projects?

Use OO to define clear module boundaries (APIs, encapsulation, service interfaces), and use FP techniques inside those boundaries (immutability, expression-oriented code, pure-ish functions) to reduce hidden state and make behavior easier to test and change.

When should I use val vs var in Scala?

Prefer val by default to avoid accidental reassignment and reduce hidden state. Reach for var intentionally in small, localized places (e.g., tight performance loops or UI glue), and keep mutation out of core business logic when possible.

When should I choose a trait over an abstract class?

Traits are reusable “capabilities” you can mix into many classes, often preventing deep, fragile hierarchies.

- Use traits for shared behavior across unrelated types and for flexible combinations.

- Use an abstract class when you need constructor parameters or centralized initialization/state (especially common in Scala 2 constraints).

How do ADTs and pattern matching make Scala code safer?

Model a closed set of states with a sealed trait plus case class/case object, then use match to handle each case.

This makes invalid states harder to represent and enables safer refactors because the compiler can warn when a new case isn’t handled.

What does Scala’s type inference buy you, and when should you add type annotations?

Type inference removes repetitive annotations so code stays compact, but still type-checked.

A common practice is to add explicit types at boundaries (public methods, module APIs, complex generics) to improve readability and stabilize compile errors without annotating every local value.

What are covariance and contravariance in Scala, in practical terms?

Variance describes how subtyping works for generic types.

- Covariant (

+A): a container can be “widened” (e.g., as ).

What are implicits (Scala 2) and givens/using (Scala 3) used for?

They’re the mechanism behind type-class style design: you provide behavior “from the outside” without modifying the original type.

- Scala 2:

implicit - Scala 3:

given/using

Scala 3 makes intent clearer (what’s provided vs what’s required), which usually improves readability and reduces “action at a distance.”

How do I choose between Futures, streams, and actors for concurrency in Scala?

Start simple and escalate only when needed:

- Futures: good for straightforward concurrent tasks and async composition.

- Streaming (with backpressure): best for long-running pipelines where throughput and memory matter.

- Actors/message passing: useful for long-lived, stateful components that coordinate via messages.

In all cases, passing immutable data helps avoid race conditions.

What are the best practices for Scala–Java interop in mixed codebases?

Treat Java/Scala boundaries as translation layers:

- Convert Java

nulltoOptionimmediately (and only convert back at the edge). - Convert Java collections to your team’s chosen Scala collection types.

- Normalize Java exceptions into a consistent error model.

- Keep Java-facing APIs simple and Java-friendly; keep internal Scala APIs idiomatic.

This keeps interop predictable and prevents Java defaults (nulls, mutation) from leaking everywhere.