Dec 22, 2025·8 min

How Server-Side Rendering Boosts Speed and SEO Results

Learn how server-side rendering (SSR) speeds up first load, improves Core Web Vitals, and helps search engines crawl and index pages more reliably.

Learn how server-side rendering (SSR) speeds up first load, improves Core Web Vitals, and helps search engines crawl and index pages more reliably.

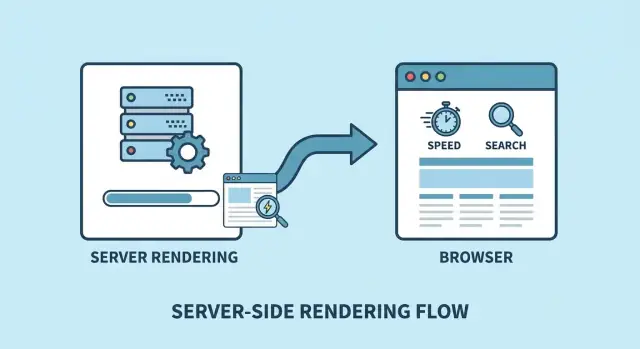

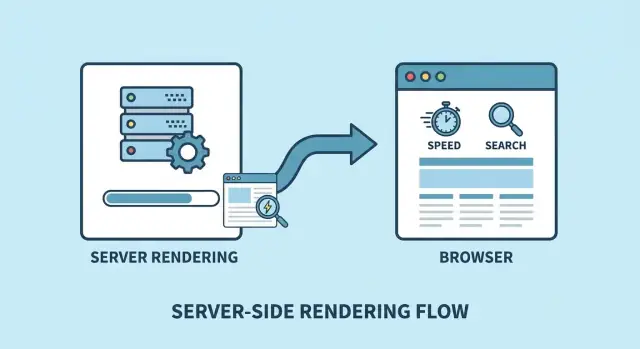

Server-side rendering (SSR) is a way to build web pages where the server prepares the first version of the page before it reaches your browser.

With a typical JavaScript app, your browser often has to download code, run it, fetch data, and then assemble the page. With SSR, the server does more of that upfront and sends back ready-to-display HTML. Your browser still downloads JavaScript afterward (for buttons, filters, forms, and other interactions), but it starts from an already-populated page instead of an empty shell.

The main “felt” difference is that content shows up sooner. Instead of staring at a blank screen or a spinner while scripts load, people can start reading and scrolling faster—especially on mobile networks or slower devices.

This earlier first view can translate into better perceived speed and can support key web performance signals like Largest Contentful Paint and, in some cases, Time to First Byte. (SSR doesn’t automatically improve everything; it depends on how your pages are built and served.)

SSR can improve web performance and help SEO for JavaScript-heavy sites, but it also introduces tradeoffs: extra server work, more things to cache, and “hydration” time (when the page becomes fully interactive).

In the rest of this article, we’ll compare SSR vs CSR in plain language, look at the performance metrics SSR can improve, explain why SSR can help crawlability and indexing, and cover the real-world costs and pitfalls—plus how to measure results with speed and SEO KPIs.

Server‑side rendering (SSR) and client‑side rendering (CSR) describe where the initial HTML for a page is produced: on the server or in the user’s browser. The difference sounds subtle, but it changes what users see first—and how quickly.

With SSR, the browser asks for a page and gets back HTML that already contains the page’s main content.

At this point, the page may look “done,” but it might not be fully interactive yet.

With CSR, the server often returns a minimal HTML shell—then the browser does more of the work.

That means users can spend more time staring at a blank area or a loading state, especially on slower connections or devices.

SSR pages typically ship HTML first, then JavaScript “hydrates” the page—attaching event handlers and turning the static HTML into a working app (buttons, forms, navigation).

A simple way to think about it:

Imagine a product page.

Server-side rendering (SSR) changes when the browser gets meaningful HTML. That shift can improve several user-facing performance metrics—but it can also backfire if your server is slow.

TTFB (Time to First Byte) measures how quickly the server starts responding. With SSR, the server may do more work (rendering HTML), so TTFB can improve (fewer client round trips) or worsen (extra render time).

FCP (First Contentful Paint) tracks when the user first sees any text or image. SSR often helps because the browser receives ready-to-paint HTML instead of a mostly empty shell.

LCP (Largest Contentful Paint) is about when the main piece of content (hero title, banner image, product photo) becomes visible. SSR can reduce the wait for the “real page” to appear—especially when the LCP element is text rendered in the initial HTML.

CLS (Cumulative Layout Shift) measures visual stability. SSR can help when it outputs consistent markup and dimensions (for images, fonts, and components). It can hurt if hydration changes the layout after the initial render.

INP (Interaction to Next Paint) reflects responsiveness during user interactions. SSR doesn’t automatically fix INP because JavaScript still needs to hydrate. You can, however, improve INP by sending less JS, splitting bundles, and deferring non-critical scripts.

Even if the page isn’t fully interactive yet, seeing content earlier improves perceived speed. Users can start reading, understanding context, and trusting that something is happening.

If your server render is expensive—database calls, heavy component trees, slow middleware—SSR can raise TTFB and delay everything.

A strong caching strategy can flip the outcome dramatically: cache full HTML for anonymous traffic, cache data responses, and use edge/CDN caching where possible. With caching, SSR can deliver fast TTFB and fast FCP/LCP.

When a page is rendered on the server, the browser receives real, meaningful HTML right away—headings, text, and primary layout are already in place. That changes the first-view experience: instead of waiting for JavaScript to download and build the page, users can start reading almost immediately.

With client-side rendering, the first response often contains a mostly empty shell (a \u003cdiv id=\"app\"\u003e and scripts). On slower connections or busy devices, that can turn into a noticeable stretch where people stare at a blank or partially styled screen.

SSR helps because the browser can paint actual content as soon as the initial HTML arrives. Even if JavaScript takes longer, the page feels alive: users see the headline, key copy, and structure, which reduces perceived waiting time and early bounces.

SSR doesn’t remove JavaScript—it changes when it’s required. After the HTML is shown, the page still needs JS to hydrate and make interactive parts work, such as:

The goal is that users can see and start understanding the page before all interactivity is ready.

If you want the first load to feel fast, prioritize SSR for the content users expect above the fold:

Done well, SSR gives users something useful immediately—then JavaScript progressively adds the polish and interactions.

Mobile performance isn’t just “desktop, but smaller.” Many users browse on mid-range phones, older devices, battery-saver modes, or in places with inconsistent connectivity. Server-side rendering (SSR) can make these scenarios feel dramatically faster because it changes where the hardest work happens.

With client-side rendering, the device often has to download JavaScript, parse it, execute it, fetch data, and then finally build the page. On slower CPUs, that “parse + execute + render” step can be the long pole.

SSR sends back HTML that already contains the initial content. The browser can start painting meaningful UI sooner, while JavaScript loads in parallel for interactivity (hydration). This reduces the amount of heavy lifting the device must do before the user sees something useful.

Lower-end phones struggle with:

By delivering a ready-to-render HTML response, SSR can shorten the time the main thread is blocked before the first paint and before key content appears.

On slower connections, every extra round trip and every extra megabyte hurts. SSR can reduce how much JavaScript is “critical” for the first screen because the initial view doesn’t depend on running a lot of code just to show content. You may still ship the same total JS for full functionality, but you can often defer non-essential code and load it after the first render.

Don’t rely on desktop Lighthouse results alone. Test with mobile throttling and real-device checks, focusing on metrics that reflect user experience on weaker devices (especially LCP and Total Blocking Time).

Search engines are very good at reading HTML. When a crawler requests a page and immediately receives meaningful, text-based HTML (headings, paragraphs, links), it can understand what the page is about and start indexing it right away.

With server-side rendering (SSR), the server returns a fully formed HTML document for the initial request. That means important content is visible in the “view source” HTML, not only after JavaScript runs. For SEO, this reduces the chances that a crawler misses key information.

With client-side rendering (CSR), the first response often contains a lightweight HTML shell and a JavaScript bundle that must download, execute, and then fetch data before the real content appears.

That can create SEO issues such as:

Google can render JavaScript for many pages, but it’s not guaranteed to be as fast or as reliable as parsing plain HTML. Rendering JavaScript requires extra steps and resources, and in practice it can mean slower discovery of content updates, delayed indexing, or occasional gaps when something in the rendering path breaks.

SSR reduces that dependency. Even if JavaScript enhances the page after load (for interactivity), the crawler already has the core content.

SSR is especially valuable for pages where getting indexed quickly and accurately matters:

If the page’s primary value is its content, SSR helps ensure search engines can see it immediately.

Server-side rendering (SSR) doesn’t just help pages load faster—it helps pages describe themselves clearly the moment they’re requested. That matters because many crawlers, link preview tools, and SEO systems rely on the initial HTML response to understand what a page is about.

At a minimum, each page should ship with accurate, page-specific metadata in the HTML:

With SSR, those tags can be rendered server-side using real page data (product name, category, article headline) rather than generic placeholders. That reduces the risk of “same title everywhere” problems that happen when metadata is injected only after JavaScript runs.

When someone shares a link in Slack, WhatsApp, LinkedIn, X, or Facebook, the platform’s scraper fetches the page and looks for Open Graph tags (and often Twitter Card tags). Examples include og:title, og:description, and og:image.

If these tags are missing from the initial HTML, the preview can fall back to something random—or show nothing at all. SSR helps because the server response already contains the correct Open Graph values for that specific URL, making previews consistent and reliable.

Structured data—most commonly JSON-LD—helps search engines interpret your content (articles, products, FAQs, breadcrumbs). SSR makes it easier to ensure the JSON-LD is delivered with the HTML and stays consistent with visible content.

Consistency matters: if your structured data describes a product price or availability that doesn’t match what’s rendered on the page, you risk rich result eligibility issues.

SSR can generate many URL variants (filters, tracking parameters, pagination). To avoid duplicate content signals, set a canonical URL per page type and ensure it’s correct for every rendered route. If you support multiple variants intentionally, define clear canonical rules and stick to them across your routing and rendering logic.

Server-side rendering shifts important work from the browser to your servers. That’s the point—and also the trade-off. Instead of each visitor’s device building the page from JavaScript, your infrastructure is now responsible for generating HTML (often on every request), plus running the same data fetching your app needs.

With SSR, spikes in traffic can translate directly into spikes in CPU, memory, and database usage. Even if the page looks simple, rendering templates, calling APIs, and preparing data for hydration adds up. You might also see higher Time to First Byte (TTFB) if rendering is slow or if upstream services (like your database) are under pressure.

Caching is how SSR stays fast without paying the full render cost every time:

Some teams render pages at “the edge” (closer to the user) to reduce round-trip time to a central server. The idea is the same: generate HTML near the visitor, while still keeping a single app codebase.

Cache wherever you can, then personalize after load.

Serve a fast cached shell (HTML + critical data), and fetch user-specific details (account info, location-based offers) after hydration. This keeps SSR speed benefits while preventing your servers from re-rendering the world for every unique visitor.

Server-side rendering (SSR) can make pages feel faster and more indexable, but it also introduces failure modes you don’t see with purely client-side apps. The good news: most issues are predictable—and fixable.

A common mistake is fetching the same data on the server to render HTML, then fetching it again on the client after hydration. That wastes bandwidth, slows interactivity, and can inflate API costs.

Avoid it by embedding initial data in the HTML (or inlined JSON) and reusing it on the client as the starting state. Many frameworks support this pattern directly—make sure your client cache is primed from the SSR payload.

SSR waits for data before it can send meaningful HTML. If your backend or third-party APIs are slow, your TTFB can spike.

Mitigations include:

It’s tempting to render everything server-side, but huge HTML responses can slow downloads—especially on mobile—and push out the point when the browser can paint.

Keep SSR output lean: render above-the-fold content first, paginate long lists, and avoid inlining excessive data.

Users might see content quickly, but the page can still feel “stuck” if the JavaScript bundle is large. Hydration can’t finish until JS downloads, parses, and runs.

Quick fixes: code splitting by route/component, defer non-critical scripts, and remove unused dependencies.

If the server renders one thing and the client renders another, you can get hydration warnings, layout shifts, or even broken UI.

Prevent mismatches by keeping rendering deterministic: avoid server-only timestamps/random IDs in markup, use consistent locale/timezone formatting, and ensure the same feature flags run on both sides.

Compress responses (Brotli/Gzip), optimize images, and adopt a clear caching strategy (CDN + server cache + client cache) to get the benefits of SSR without the headaches.

Choosing between server-side rendering (SSR), static site generation (SSG), and client-side rendering (CSR) is less about “which is best” and more about matching the rendering style to the page’s job.

SSG builds HTML ahead of time. It’s the simplest to serve fast and reliably, but can get tricky when content changes often.

SSR generates HTML on each request (or from an edge/server cache). It’s great when the page must reflect the latest user- or request-specific data.

CSR ships a minimal HTML shell and renders the UI in the browser. It can work well for highly interactive apps, but initial content and SEO can suffer if not handled carefully.

Marketing pages, docs, and blog posts usually benefit most from SSG: predictable content, great performance, and clean crawlable HTML.

Dashboards, account pages, and complex in-app tools often lean CSR (or hybrid) because the experience is driven by user interactions and private data. That said, many teams still use SSR for the initial shell (navigation, layout, first view) and then let CSR take over after hydration.

For pages that update frequently (news, listings, pricing, inventory), consider hybrid SSG with incremental regeneration (rebuilding pages on a schedule or when content changes) or SSR + caching to avoid recomputing every request.

| Page type | Best default | Why | Watch-outs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Landing pages, blog, docs | SSG | Fast, cheap to serve, SEO-friendly | Rebuild workflow for updates |

| Public content that changes often | SSR or SSG + incremental regeneration | Fresh content without full rebuilds | Cache keys, invalidation strategy |

| Personalized pages (logged-in) | SSR (with caching where safe) | Request-specific HTML | Avoid caching private data |

| Highly interactive app screens | CSR or SSR + CSR hybrid | Rich UI after initial load | Hydration cost, loading states |

A practical approach is mixed rendering: SSG for marketing, SSR for dynamic/public pages, and CSR (or SSR-hybrid) for app dashboards.

If you’re prototyping these approaches, a vibe-coding platform like Koder.ai can help you spin up a React web app with a Go + PostgreSQL backend via chat, then iterate on SSR/SSG choices, export the source code, and deploy/host with rollback support. It’s a useful way to validate performance and SEO assumptions quickly before committing to a full rebuild.

SSR is only worth it if it measurably improves user experience and search visibility. Treat it like a performance experiment: capture a baseline, ship safely, then compare the same metrics after rollout.

On the speed side, focus on Core Web Vitals and a couple of supporting timings:

On the SEO side, measure how crawl and indexing change:

Use Lighthouse for a quick directional read, WebPageTest for repeatable lab runs and filmstrips, and Search Console for crawl/indexing trends. For root-cause analysis, add server logs/APM to see real TTFB, cache hit rate, and error spikes.

Prefer A/B testing (split traffic) or a phased rollout (e.g., 5% → 25% → 100%). Compare the same page templates and device/network profiles so results aren’t skewed.

SSR (server-side rendering) means your server sends back HTML that already contains the page’s main content.

Your browser can render that HTML immediately, then download JavaScript afterward to “hydrate” the page and enable interactivity (buttons, forms, filters).

CSR (client-side rendering) typically sends a minimal HTML shell and relies on the browser to run JavaScript, fetch data, and build the UI.

SSR sends meaningful HTML up front, so users see content sooner, while CSR often shows a blank area or loading state until JavaScript finishes.

Hydration is the step where JavaScript attaches event handlers to the server-rendered HTML so the page becomes interactive.

A page can look “done” after SSR, but still feel unresponsive until hydration completes—especially if the JS bundle is large.

SSR can improve:

It may or may not improve TTFB, depending on how expensive server rendering and data fetching are.

SSR helps reduce the “blank page” phase by delivering real HTML content immediately.

Even if the page isn’t interactive yet, users can read, scroll, and understand context sooner, which often lowers perceived wait time and early bounces.

SSR can make performance worse when server rendering is slow (heavy component trees, slow APIs/DB queries, expensive middleware), which increases TTFB.

Mitigate with caching (full-page/fragment/CDN), timeouts and fallbacks for non-critical data, and keeping SSR output lean.

SSR usually helps SEO because crawlers immediately receive meaningful HTML (headings, paragraphs, links) without relying on JavaScript execution.

That reduces risks common with CSR, like thin initial content, delayed discovery of internal links, or indexing gaps when JS fails or times out.

SSR makes it easier to return page-specific metadata in the initial HTML, including:

<title> and meta descriptionThis improves search snippets and makes social link previews more reliable because many scrapers don’t execute JavaScript.

Common pitfalls include:

Fixes: reuse SSR “initial data” on the client, keep rendering deterministic, split/defer JS, and paginate or trim above-the-fold SSR output.

Use SSG for mostly static pages (blogs, docs, marketing) where speed and simplicity matter.

Use SSR for pages that must reflect fresh or request-specific data (listings, pricing, some personalized experiences), ideally with caching.

Use CSR (or SSR + CSR hybrid) for highly interactive, logged-in app screens where SEO is less important and interactivity dominates.