May 07, 2025·8 min

How Database Sharding Works—and Why It’s Hard to Reason About

Sharding scales databases by splitting data across nodes, but it adds routing, rebalancing, and new failure modes that make systems harder to reason about.

Sharding scales databases by splitting data across nodes, but it adds routing, rebalancing, and new failure modes that make systems harder to reason about.

Sharding (also called horizontal partitioning) means taking what looks like one database to your application and splitting its data across multiple machines, called shards. Each shard holds only a subset of the rows, but together they represent the full dataset.

A helpful mental model is the difference between logical structure and physical placement.

From the app’s point of view, you want to run queries like it’s one table. Under the hood, the system must decide which shard(s) to talk to.

Sharding is different from replication. Replication creates copies of the same data on multiple nodes, mainly for high availability and read scaling. Sharding splits the data so each node holds different records.

It’s also different from vertical scaling, where you keep one database but move it to a bigger machine (more CPU/RAM/faster disks). Vertical scaling can be simpler, but has practical limits and can get expensive quickly.

Sharding increases capacity, but it doesn’t automatically make your database “easy” or every query faster.

So sharding is best understood as a way to scale storage and throughput—not a free upgrade to every aspect of database behavior.

Sharding is rarely someone’s first choice. Teams usually reach for it after a successful system hits physical limits—or after operational pain becomes too frequent to ignore. The motivation is less “we want sharding” and more “we need a way to keep growing without one database becoming a single point of failure and cost.”

A single database node can run out of room in several different ways:

When these issues show up regularly, the problem is often not a single bad query—it’s that one machine is carrying too much responsibility.

Database sharding spreads data and traffic across multiple nodes so capacity grows by adding machines instead of vertically upgrading one. Done well, it can also isolate workloads (so one tenant’s spike doesn’t ruin latency for others) and control costs by avoiding ever-larger premium instances.

Recurring patterns include steadily rising p95/p99 latency during peak, longer replication lag, backups/restores exceeding your acceptable window, and “small” schema changes becoming major events.

Before committing, teams typically exhaust simpler options: indexing and query fixes, caching, read replicas, partitioning within a single database, archiving old data, and hardware upgrades. Sharding can solve scale, but it also adds coordination, operational complexity, and new failure modes—so the bar should be high.

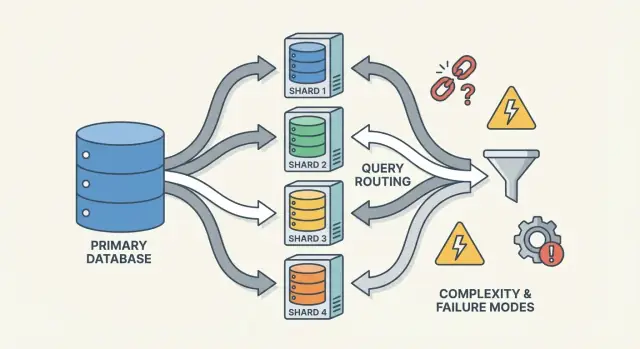

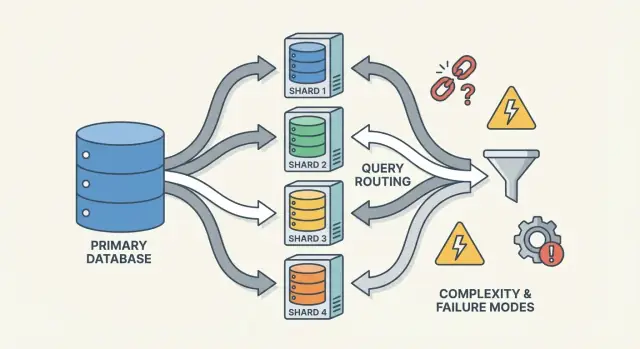

A sharded database isn’t one thing—it’s a small system of cooperating parts. The reason sharding can feel “hard to reason about” is that correctness and performance depend on how these pieces interact, not just on the database engine.

A shard is a subset of the data, usually stored on its own server or cluster. Each shard typically has its own:

From an application’s point of view, a sharded setup often tries to look like one logical database. But under the hood, a query that would be “one index lookup” in a single-node database might become “find the right shard, then do the lookup.”

A router (sometimes called a coordinator, query router, or proxy) is the traffic cop. It answers the practical question: given this request, which shard should handle it?

There are two common patterns:

Routers reduce complexity in the app, but they can also become a bottleneck or a new failure point if not designed carefully.

Sharding relies on metadata—a source of truth describing:

This information often lives in a config service (or a small “control plane” database). If metadata is stale or inconsistent, routers can send traffic to the wrong place—even if every shard is perfectly healthy.

Finally, sharding depends on background processes that keep the system livable over time:

These jobs are easy to ignore early on, but they’re where many production surprises happen—because they change the shape of the system while it’s still serving traffic.

A shard key is the field (or combination of fields) your system uses to decide which shard should store a row/document. That single choice quietly determines performance, cost, and even which features feel “easy” later—because it controls whether requests can be routed to one shard or have to fan out to many.

A good key tends to have:

A common example is sharding by tenant_id in a multi-tenant app: most reads and writes for a tenant stay on one shard, and tenants are numerous enough to spread load.

Some keys almost guarantee pain:

Even if a low-cardinality key seems convenient for filtering, it often turns routine queries into scatter-gather queries, because matching rows live everywhere.

The best shard key for load balancing isn’t always the best shard key for product queries.

user_id), and some “global” queries (e.g., admin reporting) become slower or require separate pipelines.region), and you risk hotspots and uneven capacity.Most teams design around this trade-off: optimize the shard key for the most frequent, latency-sensitive operations—and handle the rest with indexes, denormalization, replicas, or dedicated analytics tables.

There isn’t one “best” way to shard a database. The strategy you pick shapes how easy it is to route queries, how evenly data spreads, and what kinds of access patterns will hurt.

With range sharding, each shard owns a contiguous slice of a key space—for example:

Routing is straightforward: look at the key, choose the shard.

The catch is hotspots. If new users always get increasing IDs, the “last” shard becomes the write bottleneck. Range sharding is also sensitive to uneven growth (one range gets popular, another stays quiet). The upside: range queries (“all orders from Oct 1–Oct 31”) can be efficient because the data is physically grouped.

Hash sharding runs the shard key through a hash function and uses the result to pick a shard. This typically spreads data more evenly, which helps avoid the “everything is going to the newest shard” problem.

Trade-off: range queries become painful. A query like “customers with IDs between X and Y” no longer maps to a small set of shards; it may touch many.

A practical detail teams often underestimate is consistent hashing. Instead of mapping directly to shard count (which reshuffles everything when you add shards), many systems use a hash ring with “virtual nodes” so adding capacity moves only a portion of keys.

Directory sharding stores an explicit mapping (a lookup table/service) from key → shard location. This is the most flexible: you can place specific tenants on dedicated shards, move one customer without moving everyone else, and support uneven shard sizes.

The downside is an extra dependency. If the directory is slow, stale, or unavailable, routing suffers—even if the shards are healthy.

Real systems often blend approaches. A composite shard key (e.g., tenant_id + user_id) keeps tenants isolated while spreading load within a tenant. Sub-sharding is similar: first route by tenant, then hash within that tenant’s shard group to avoid a single “big tenant” dominating one shard.

A sharded database has two very different “query paths.” Understanding which path you’re on explains most surprises in performance—and why sharding can feel unpredictable.

The ideal outcome is routing a query to exactly one shard. If the request includes the shard key (or something the router can map to the shard), the system can send it straight to the right place.

That’s why teams obsess over making common reads “shard-key aware.” One shard means fewer network hops, simpler execution, fewer locks, and far less coordination. Latency is mostly the database doing the work, not the cluster arguing about who should do it.

When a query can’t be routed precisely (for example, it filters on a non-shard-key field), the system may broadcast it to many or all shards. Each shard runs the query locally, then the router (or a coordinator) merges results—sorting, deduplicating, applying limits, and combining partial aggregates.

This fan-out amplifies tail latency: even if 9 shards respond quickly, one slow shard can hold the whole request hostage. It also multiplies load: one user request can become N shard requests.

Joins across shards are expensive because data that would meet “inside” the database must now travel between shards (or to a coordinator). Even simple aggregations (COUNT, SUM, GROUP BY) can require a two-phase plan: compute partial results on each shard, then merge them.

Most systems default to local indexes: each shard indexes only its own data. They’re cheap to maintain, but they don’t help routing—so queries may still scatter.

Global indexes can enable targeted routing on non-shard-key fields, but they add write overhead, extra coordination, and their own scaling and consistency headaches.

Writes are where sharding stops feeling like “just scaling” and starts changing how you design features. A write that touches one shard can be fast and simple. A write that spans shards can be slow, failure-prone, and surprisingly hard to make correct.

If each request can be routed to exactly one shard (typically via a shard key), the database can use its normal transaction machinery. You get atomicity and isolation within that shard, and most operational issues look like familiar single-node problems—just repeated N times.

The moment you need to update data on two shards in one “logical action” (e.g., transfer money, move an order between customers, update an aggregate stored elsewhere), you’re in distributed transaction territory.

Distributed transactions are hard because they require coordination between machines that can be slow, partitioned, or restarted at any time. Two-phase commit–style protocols add extra round trips, can block on timeouts, and make failures ambiguous: did shard B apply the change before the coordinator died? If the client retries, do you double-apply the write? If you don’t retry, do you lose it?

A few common tactics reduce how often you need multi-shard transactions:

In sharded systems, retries aren’t optional—they’re inevitable. Make writes idempotent by using stable operation IDs (e.g., an idempotency key) and having the database store “already applied” markers. That way, if a timeout occurs and the client retries, the second attempt becomes a no-op instead of a double charge, duplicate order, or inconsistent counter.

Sharding splits your data across machines, but it doesn’t remove the need for redundancy. Replication is what keeps a shard available when a node dies—and it’s also what makes “what is true right now?” harder to answer.

Most systems replicate within each shard: one primary (leader) node accepts writes, and one or more replicas copy those changes. If the primary fails, the system promotes a replica (failover). Replicas can also serve reads to reduce load.

The trade-off is timing. A read replica may be a few milliseconds—or seconds—behind. That gap is normal, but it matters when users expect “I just updated it, so I should see it.”

In sharded setups, you often end up with strong consistency within a shard and weaker guarantees across shards, especially when multi-shard operations are involved.

With sharding, “single source of truth” typically means: for any given piece of data, there is one authoritative place to write it (usually the shard’s leader). But globally, there isn’t one machine that can instantly confirm the latest state of everything. You have many local truths that must be kept in sync through replication.

Constraints are tricky when the data that needs to be checked lives on different shards:

These choices aren’t just implementation details—they define what “correct” means for your product.

Rebalancing is what keeps a sharded database usable as reality changes. Data grows unevenly, a “balanced” shard key drifts into skew, you add new nodes for capacity, or you need to retire hardware. Any of those can turn one shard into the bottleneck—even if the original design looked perfect.

Unlike a single database, sharding bakes the location of data into routing logic. When you move data, you’re not just copying bytes—you’re changing where queries must go. That means rebalancing is as much about metadata and clients as it is about storage.

Most teams aim for an online workflow that avoids a big “stop the world” window:

A shard map change is a breaking event if clients cache routing decisions. Good systems treat routing metadata like configuration: version it, refresh it frequently, and be explicit about what happens when a client hits a moved key (redirect, retry, or proxy).

Rebalancing often causes temporary performance dips (extra writes, cache churn, background copy load). Partial moves are common—some ranges migrate before others—so you need clear observability and a rollback plan (for example, flipping the map back and draining dual-writes) before starting the cutover.

Sharding assumes work will spread out. The surprise is that a cluster can look “even” on paper (same number of rows per shard) while behaving wildly uneven in production.

A hotspot happens when a small slice of your keyspace gets most of the traffic—think a celebrity account, a popular product, a tenant running a heavy batch job, or a time-based key where “today” attracts all writes. If those keys map to one shard, that shard becomes the bottleneck even if every other shard is idle.

“Skew” isn’t one thing:

They don’t always match. A shard with less data can still be the hottest if it owns the most requested keys.

You don’t need fancy tracing to spot skew. Start with per-shard dashboards:

If one shard’s latency rises with its QPS while others stay flat, you likely have a hotspot.

Fixes usually trade simplicity for balance:

Sharding doesn’t just add more servers—it adds more ways for things to go wrong, and more places to look when they do. Many incidents aren’t “the database is down,” but “one shard is down,” or “the system can’t agree on where data lives.”

A few patterns show up repeatedly:

In a single-node database, you tail one log and check one set of metrics. In a sharded system, you need observability that follows a request across shards.

Use correlation IDs in every request and propagate them from the API layer through routers to each shard. Pair that with distributed tracing so a scatter-gather query shows which shard was slow or failed. Metrics should be broken down per shard (latency, queue depth, error rate), otherwise a hot shard hides inside fleet averages.

Sharding failures often show up as correctness bugs:

“Restore the database” becomes “restore many parts in the right order.” You may need to restore metadata first, then each shard, then verify shard boundaries and routing rules match the restored point-in-time. DR plans should include rehearsals that prove you can reassemble a consistent cluster—not just recover individual machines.

Sharding is often treated as the “scaling switch,” but it’s also a permanent increase in system complexity. If you can meet your performance and reliability goals without splitting data across nodes, you’ll usually get a simpler architecture, easier debugging, and fewer operational edge cases.

Before committing to sharding, try options that preserve a single logical database:

One practical way to de-risk sharding is to prototype the plumbing (routing boundaries, idempotency, migration workflows, and observability) before you commit your production database to it.

For example, with Koder.ai you can quickly spin up a small, realistic service from chat—often a React admin UI plus a Go backend with PostgreSQL—and experiment with shard-key-aware APIs, idempotency keys, and “cutover” behaviors in a safe sandbox. Because Koder.ai supports planning mode, snapshots/rollback, and source code export, you can iterate on sharding-related design decisions (like routing and metadata shape) and then carry the resulting code and runbooks into your main stack when you’re confident.

Sharding is a better fit when your dataset or write throughput clearly exceeds a single node’s limits and your query patterns can reliably use a shard key (few cross-shard joins, minimal scatter-gather queries).

It’s a poor fit when your product needs lots of ad-hoc queries, frequent multi-entity transactions, global uniqueness constraints, or when the team can’t support the operational workload (rebalancing, resharding, incident response).

Ask:

Even if you delay sharding, design a migration path: choose identifiers that won’t block a future shard key, avoid hard-coding single-node assumptions, and rehearse how you’d move data with minimal downtime. The best time to plan resharding is before you need it.

Sharding (horizontal partitioning) splits a single logical dataset across multiple machines (“shards”), where each shard stores different rows.

Replication, in contrast, keeps copies of the same data on multiple nodes—primarily for availability and read scaling.

Vertical scaling means upgrading one database server (more CPU/RAM/faster disks). It’s simpler operationally, but you eventually hit hard limits (or steep cost).

Sharding scales out by adding more machines, but introduces routing, rebalancing, and cross-shard correctness challenges.

Teams shard when one node becomes a recurring bottleneck, such as:

Sharding spreads data and traffic so capacity increases by adding nodes.

A typical sharded system includes:

Performance and correctness depend on these pieces staying consistent.

A shard key is the field(s) used to decide where a row lives. It largely determines whether requests hit one shard (fast) or many shards (slow).

Good shard keys usually have high cardinality, even distribution, and match your common access patterns (e.g., tenant_id or user_id).

Common “bad” shard keys include:

These often cause hotspots or turn routine queries into scatter-gather fan-outs.

Three common strategies are:

If a query includes the shard key (or something that maps to it), the router can send it to one shard—the fast path.

If it can’t be routed precisely, it may fan out to many/all shards (scatter-gather). One slow shard can dominate latency, and each user query becomes N shard queries.

Single-shard writes can use normal transactions on that shard.

Cross-shard writes require distributed coordination (often two-phase-commit-like behavior), which increases latency and failure ambiguity. Practical mitigations include:

Before sharding, try options that preserve a single logical database:

Sharding is a better fit when you’ve exceeded single-node limits and most critical queries can be shard-key-routed with minimal cross-shard joins/transactions.