Aug 29, 2025·8 min

How to Build a Modern Web App: From Idea to Launch

Learn the practical steps to build a modern web app: planning, tech stack, frontend and backend setup, data, auth, testing, deployment, and monitoring.

Learn the practical steps to build a modern web app: planning, tech stack, frontend and backend setup, data, auth, testing, deployment, and monitoring.

Before wireframes or tech choices, get clear on what you’re building and how you’ll know it’s working.

A modern web app isn’t just “a site with login.” It typically includes a responsive UI that works well on mobile and desktop, fast page loads and interactions, sensible security defaults, and a codebase that’s maintainable (so changes don’t become painful every sprint). “Modern” also implies the product can evolve—features can be shipped, measured, and improved without rebuilding everything.

Define 1–2 primary user types and describe their core job-to-be-done in plain language. For example: “A clinic admin needs to confirm appointments quickly and reduce no-shows.” If you can’t explain the problem in one sentence, you’ll struggle to prioritize features later.

A quick way to sharpen this is to write:

Constraints drive better decisions. Capture realities like budget and timeline, team skills, required integrations, and compliance needs (e.g., GDPR/PCI/HIPAA). Also note key assumptions—things you’re betting on—so you can test them early.

Pick a few metrics that reflect real value, not vanity. Common options:

When you align goals, users, constraints, and KPIs upfront, the rest of the build becomes a series of clearer trade-offs instead of guesswork.

A web app fails more often from unclear scope than from “bad code.” Before you open an editor, write down what you’re building, for whom, and what won’t be included yet. This keeps decisions consistent when new ideas show up mid-build.

Keep it to 2–3 sentences:

Example: “A booking app for independent tutors to manage availability and accept paid reservations. The first version supports one tutor account, basic scheduling, and Stripe payments. Success is 20 completed bookings in the first month.”

Create a single list of features, then rank them by user value and effort. A quick approach is:

Be strict: if a feature isn’t needed for the first real user to complete the main task, it’s probably “Later.”

User flows are simple step-by-step paths (e.g., “Sign up → Create project → Invite teammate → Upload file”). Draw them on paper or in a doc. This reveals missing steps, confusing loops, and where you need confirmations or error states.

Use rough wireframes to decide layout and content without debating colors or fonts. Then build a clickable prototype to test with 3–5 target users. Ask them to complete one task while thinking aloud—early feedback here can save weeks of rework later.

If you want to move from scope to a working skeleton quickly, a vibe-coding platform like Koder.ai can help you turn user flows into a React UI + API scaffold via chat, then iterate while your KPIs and constraints are still fresh.

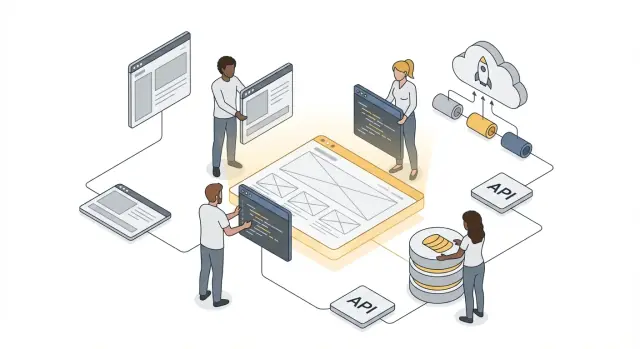

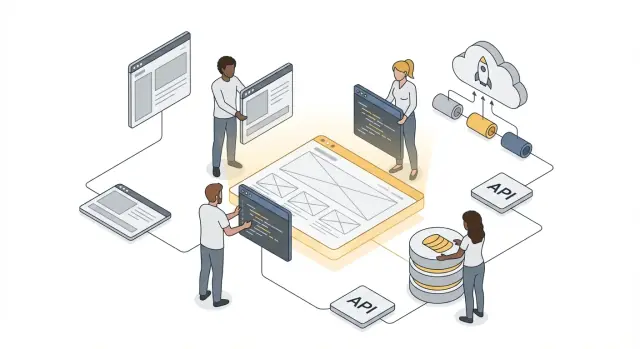

Architecture is the set of choices that decide how your app is put together and where it runs. The right answer depends less on what’s “best” and more on your constraints: team size, how fast you need to ship, and how uncertain the product is.

For most new products, start with a modular monolith: one deployable app, but internally organized by clear modules (users, billing, content, etc.). It’s faster to build, easier to debug, and simpler to deploy—especially for a small team.

Move toward multiple services (or separate apps) when you have a strong reason:

A common trap is splitting too early and spending weeks on coordination and infrastructure instead of user value.

You generally have three practical options:

If you don’t have someone who enjoys “owning production,” pick the most managed option you can.

At minimum, most modern web apps include:

Draw this as a simple box diagram and note what talks to what.

Before building, document basics like an uptime target, acceptable latency, data retention, and any compliance needs. These constraints drive architecture more than preferences—and prevent painful redesigns later.

Your tech stack should support the product you’re building and the team you have. The best choice is usually the one that helps you ship reliably, iterate quickly, and keep hiring and maintenance realistic.

If your app has interactive screens, shared UI components, client-side routing, or complex state (filters, dashboards, real-time updates), a modern framework is worth it.

If your UI is mostly static pages with a few interactive widgets, you may not need a full single-page app. A simpler setup (server-rendered pages + a small amount of JS) can reduce complexity.

Backends succeed when they’re boring, predictable, and easy to operate.

A good rule: pick the backend language your team can debug at 2 a.m.—not the one that looked best in a demo.

For most web apps, start with a relational database:

Choose NoSQL when your data is truly document-like, your access patterns demand it, or you’re already sure you’ll benefit from its scaling model. Otherwise, it can add complexity (data consistency, reporting, migrations).

Trendy stacks can be great—but only with clear benefits. Before committing, ask:

Aim for a stack that keeps your product flexible without turning every change into a refactor project.

The frontend is where users decide whether your app feels “easy” or “hard.” A good UI isn’t just pretty—it’s consistent, accessible, and resilient when data is slow, missing, or wrong.

Start with a small set of rules you can reuse everywhere:

You don’t need a full design team to do this—just enough structure that every screen feels like the same product.

Bake in the essentials early:

These choices reduce support tickets and expand who can use your app.

Use local state for isolated UI (toggle, open/close, input typing). Introduce global state only when multiple areas must stay in sync (current user, cart, theme, notifications). A common trap is adding heavy global tools before you actually have shared-state pain.

Decide patterns for:

Consistency here makes your app feel polished—even before it’s feature-complete.

Your backend is the “source of truth” for data, permissions, and business rules. The fastest way to keep frontend and backend aligned is to treat the API contract as a product artifact: agree on it early, write it down, and keep changes visible.

Most teams choose REST (clear URLs, works well with caching and simple clients) or GraphQL (clients can request exactly the fields they need). Either can work for a modern web app—what matters is consistency. Mixing styles without a plan often leads to confusing data access patterns and duplicate logic.

Before implementation, sketch the main resources (for REST) or types/operations (for GraphQL). Define:

Doing this upfront prevents the common cycle of “ship it now, patch it later” that creates brittle integrations.

Validate inputs at the boundary: required fields, formats, and permission checks. Return helpful errors that the UI can display.

For changes, version carefully. Prefer backward-compatible evolution (add fields, don’t rename/remove) and only introduce a new version when you must. Document key decisions in an API reference (OpenAPI for REST, schema docs for GraphQL) plus short examples that show real usage.

Many features rely on work that shouldn’t block a user request:

Define these flows as part of the contract too: payloads, retries, and failure handling.

Good data design makes a web app feel “solid” to users: it’s fast, consistent, and hard to break. You don’t need a perfect schema on day one, but you do need a clear starting point and a safe way to change it.

List the nouns your product can’t live without—users, teams, projects, orders, subscriptions, messages—and describe how they relate.

A quick sanity check:

Keep it practical: model what you need for the next few releases, not every future scenario.

Indexes are what make common queries fast (e.g., “find orders by user” or “search projects by name”). Start by indexing fields you filter or sort by often, and any “lookup” fields like email.

Add guardrails where they belong:

Treat database migrations like version control for your schema. Make changes in small steps (add a column, backfill data, then switch reads/writes) so releases stay safe.

Don’t store big files directly in your database. Use an object storage service (like S3-compatible storage) and keep only metadata in the database (file URL, owner, size, type). This keeps backups lighter and performance steadier.

Set up automated backups early, test a restore process, and define who can run it. A backup you’ve never restored is a guess—not a plan.

Security is easiest to get right when you decide the basics early: how users log in, what they can do, and how your app protects itself from common abuse.

Session-based auth stores a session ID in a cookie and keeps session state on the server (or a shared store like Redis). It’s a strong default for traditional web apps because cookies work smoothly with browsers and revocation is straightforward.

Token-based auth (often JWTs) sends a token on every request (usually in an Authorization header). It’s convenient for APIs consumed by mobile apps or multiple clients, but requires careful handling of expiration, rotation, and revocation.

If your product is primarily browser-based, start with cookie + session. If you have multiple external clients, consider tokens—but keep them short-lived and avoid storing long-lived tokens in the browser.

HttpOnly, , and appropriate settings.Authentication answers “who are you?” Authorization answers “what are you allowed to do?” Define roles (e.g., admin, member) and permissions (e.g., manage_users, view_billing). Enforce authorization server-side on every request—never rely on the UI to hide buttons as protection.

A practical approach is a simple role-based system at first, evolving to more granular permissions as your app grows.

Treat secrets (API keys, DB passwords) as configuration, not code: store them in environment variables or a secrets manager, and rotate them when staff changes.

For sensitive user data, minimize what you collect, encrypt where appropriate, and log carefully (avoid printing tokens, passwords, or full credit card details).

Shipping quickly is good—shipping safely is better. A clear testing strategy helps you catch regressions early, keep changes predictable, and avoid “fix one thing, break two” releases.

Aim for a healthy mix of tests, with more coverage at the bottom of the pyramid:

A practical rule: automate what breaks often and what costs the most to fix in production.

Make quality the default by running checks on every change:

Hook these into your pull requests so problems are found before they merge.

Tests fail for two main reasons: real bugs, or unstable setups. Reduce flakiness by:

Before each release, confirm:

Performance is a product feature. Slow pages reduce conversions, and slow APIs make everything feel unreliable. The goal isn’t to “optimize everything,” but to measure, fix the biggest bottlenecks, and keep regressions from sneaking in.

Start with a small set of metrics you can track over time:

A simple rule: if you can’t chart it, you can’t manage it.

Most wins come from reducing work on the critical path:

Also watch third-party scripts—they often become the hidden reason your app feels heavy.

Backend performance is usually about doing less per request:

Add caching layers (Redis, CDN, query caching) only when profiling shows a need. Caches can speed things up, but they also introduce invalidation rules, extra failure modes, and operational overhead.

If you want a simple habit: profile monthly, load test before major launches, and treat performance regressions like bugs—not “nice-to-haves.”

Deployment is where a promising web app either becomes reliable—or turns into a string of late-night “why is production different?” surprises. A little structure here saves time later.

Aim for three environments: local, staging, and production. Keep them as similar as practical (same runtime versions, similar configuration, same database engine). Put configuration in environment variables and document them in a template (for example, .env.example) so every developer and CI runner uses the same knobs.

Staging should mirror production behavior, not just “a test server.” It’s where you validate releases with real deployment steps and realistic data volume.

A basic CI/CD pipeline should:

main)Keep the pipeline simple at first, but make it strict: no deploy if tests fail. This is one of the easiest ways to improve product quality without extra meetings.

If your app uses more than a single service, consider infrastructure-as-code so environments can be recreated predictably. It also makes changes reviewable, like application code.

Plan how you’ll undo a bad release: versioned deployments, a quick “previous version” switch, and database migration safeguards.

Finally, add a lightweight release notes process: what shipped, what changed, and any follow-up tasks. It helps support, stakeholders, and your future self.

Shipping is the start of the real work: keeping your app reliable while learning what users actually do. A simple monitoring and maintenance plan prevents small issues from turning into expensive outages.

Aim for “answers on demand.”

If you use a central dashboard, keep naming consistent (the same service and endpoint names across charts and logs).

Alerts should be actionable. Set thresholds for:

Start with a small set of alerts and tune them after a week. Too many alerts get ignored.

Track only what you’ll use: activation steps, key feature usage, conversion, and retention. Document the goal for each event, and review it quarterly.

Be explicit about privacy: minimize personal data, set retention limits, and provide clear consent where required.

Create a lightweight cadence:

A maintained app stays faster to develop, safer to run, and easier to trust.

If you’re looking to reduce maintenance overhead early, Koder.ai can be useful as a fast baseline: it generates a React frontend with a Go backend and PostgreSQL, supports deployment and hosting, and lets you export source code so you can keep full ownership as the product matures.

Start by writing:

This keeps scope and technical decisions tied to measurable outcomes instead of opinions.

Use a short scope statement (2–3 sentences) that names:

Then list features and label them , , and . If it isn’t needed for a real user to complete the main workflow, it’s likely not MVP.

Map the simplest step-by-step path for key tasks (for example: Sign up → Create project → Invite teammate → Upload file). User flows help you spot:

Do this before high-fidelity UI so you don’t “polish” the wrong flow.

Create rough wireframes and then a clickable prototype. Test with 3–5 target users by asking them to complete one core task while thinking aloud.

Focus on:

This kind of early test often saves weeks of rework.

For most early-stage products, start with a modular monolith:

Split into multiple services only when you have clear pressure (independent scaling needs, multiple teams blocking each other, strict isolation like payments). Splitting too early usually adds infrastructure work without adding user value.

Pick the most managed option that fits your team:

If nobody on the team wants to “own production,” lean toward managed hosting.

Choose a stack that helps you ship reliably and iterate with your current team:

Avoid choosing solely for trendiness; ask whether it reduces time-to-ship in the next 8–12 weeks and what your rollback plan is if it slows you down.

Treat the API contract as a shared artifact and define early:

Pick one primary style (REST or GraphQL) and apply it consistently to avoid duplicated logic and confusing data access patterns.

Start by modeling core entities and relationships (users, teams, orders, etc.). Then add:

Also set up automated backups and test restores early—untested backups aren’t a real plan.

For browser-first apps, cookie + session authentication is often the simplest strong default. Regardless of method, ship these basics:

HttpOnly, , appropriate )SecureSameSiteSecureSameSiteAnd enforce authorization server-side on every request (roles/permissions), not just by hiding UI buttons.