Jun 16, 2025·8 min

How to Build a Web App for Project Dependency Management

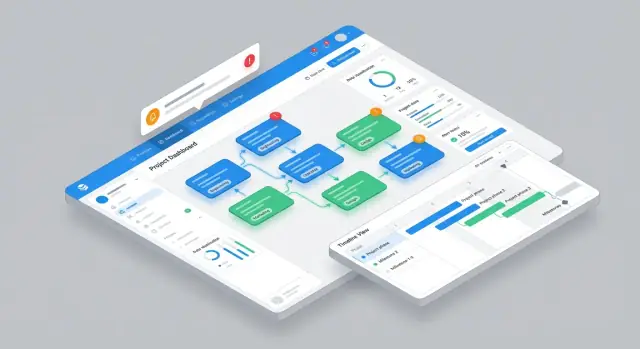

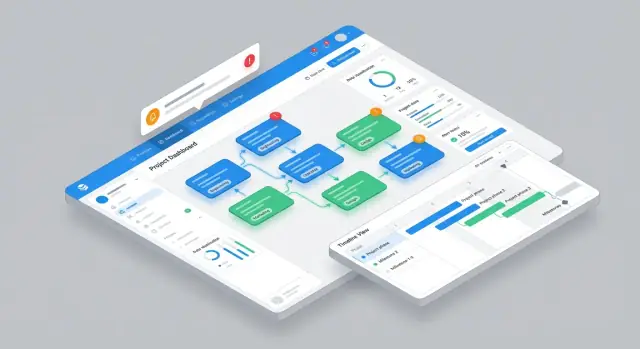

Plan, design, and ship a web app that tracks cross-functional project dependencies, owners, risks, and timelines with clear workflows, alerts, and reporting.

Plan, design, and ship a web app that tracks cross-functional project dependencies, owners, risks, and timelines with clear workflows, alerts, and reporting.

Before you design screens or pick a tech stack, get precise about the problem you’re solving. A dependency app fails when it becomes “another place to update,” while the real pain—surprises and late handoffs between teams—continues.

Start with a simple statement you can repeat in every meeting:

Cross-functional dependencies are causing delays and last‑minute surprises because ownership, timing, and status are unclear.

Make it specific to your organization: which teams are most affected, what types of work get blocked, and where you currently lose time (handoffs, approvals, deliverables, data access, etc.).

List the primary users and how they will use the app:

Keep the “jobs” tight and testable:

Write a one-paragraph definition. Examples: a handoff (Team A provides data), an approval (Legal sign-off), or a deliverable (Design spec). This definition becomes your data model and workflow backbone.

Choose a small set of measurable outcomes:

If you can’t measure it, you can’t prove the app is improving execution.

Before you design screens or databases, get clear on who participates in dependencies and how work moves between them. Cross-functional dependency management fails less from bad tooling and more from mismatched expectations: “Who owns it?”, “What does done mean?”, “Where do we see status?”

Dependency information is usually scattered. Do a quick inventory and capture examples (real screenshots or links) of:

This tells you what fields people already rely on (due dates, links, priority) and what’s missing (clear owner, acceptance criteria, status).

Write the current flow in plain language, typically:

request → accept → deliver → verify

For each step, note:

Look for patterns like unclear owners, missing due dates, “silent” status, or dependencies discovered late. Ask stakeholders to rank the most painful scenarios (e.g., “accepted but never delivered” vs. “delivered but not verified”). Optimize the top 1–2 first.

Write 5–8 user stories that reflect reality, such as:

These stories become your scope guardrails when feature requests start piling up.

A dependency app succeeds or fails on whether everyone trusts the data. The goal of your data model is to capture who needs what, from whom, by when, and to keep a clean record of how commitments change over time.

Start with a single “Dependency” entity that is readable on its own:

Keep these fields mandatory where possible; optional fields tend to become empty fields.

Dependencies are really about time, so store dates explicitly and separately:

This separation prevents arguments later (“requested” is not the same as “committed”).

Use a simple, shared status model: proposed → pending → accepted → delivered, with exceptions like at risk and rejected.

Model relationships as one-to-many links so each dependency can connect to:

Make changes traceable with:

If you get the audit trail right early, you’ll avoid “he said/she said” debates and make handoffs smoother.

A dependency app only works if everyone agrees on what a “project” is, what a “milestone” is, and who is accountable when things slip. Keep the model simple enough that teams will actually maintain it.

Track projects at the level people plan and report on—usually an initiative that lasts weeks to months and has a clear outcome. Avoid creating a project for every ticket; that belongs in delivery tools.

Milestones should be few, meaningful checkpoints that can unblock others (e.g., “API contract approved,” “Beta launch,” “Security review complete”). If milestones get too detailed, updates become a chore and data quality drops.

A practical rule: projects should have 3–8 milestones, each with an owner, target date, and status. If you need more, consider making the project smaller.

Dependencies fail when people don’t know who to talk to. Add a lightweight team directory that supports:

This directory should be usable even by non-technical partners, so keep fields human-readable and searchable.

Decide upfront whether you allow shared ownership. For dependencies, the cleanest rule is:

If two teams truly share responsibility, model it as two milestones (or two dependencies) with a clear handoff, instead of “co-owned” items that no one drives.

Represent dependencies as links between a requesting project/milestone and a delivering project/milestone, with a direction (“A needs B”). This enables program views later: you can roll up by initiative, quarter, or portfolio without changing how teams work day to day.

Tags help slice reporting without forcing a new hierarchy. Start with a small, controlled set:

Prefer dropdowns over free text for core tags to avoid “Payments,” “payments,” and “Paymnts” becoming three different categories.

A dependency management app succeeds when people can answer two questions in seconds: “What do I owe?” and “What’s blocking me?” Design navigation around those jobs-to-be-done, not around database objects.

Start with four core views, each optimized for a different moment in the week:

Keep global navigation minimal (e.g., Inbox, Dependencies, Timeline, Reports), and let users jump between views without losing their filters.

Make creating a dependency feel as quick as sending a message. Provide templates (e.g., “API contract,” “Design review,” “Data export”) and a Quick Add drawer.

Require only what’s necessary to route work correctly: requesting team, owning team, due date, short description, and status. Everything else can be optional or progressively disclosed.

People will live in filters. Support search and filters by team, date range, risk, status, project, plus “assigned to me.” Allow users to save common combinations (“My Q1 launches,” “High risk this month”).

Use color-safe risk indicators (icon + label, not color alone) and ensure full keyboard navigation for creating, filtering, and updating statuses.

Empty states should teach. When a list is empty, show a short example of a strong dependency:

“Payments team: provide sandbox API keys for Checkout v2 by Mar 14; needed for mobile QA start.”

That kind of guidance improves data quality without adding process.

A dependency tool succeeds when it mirrors how teams actually collaborate—without forcing people into long status meetings. Design the workflow around a small set of states that everyone can recognize, and make every state change answer one question: “What happens next, and who owns it?”

Start with a guided “Create dependency” form that captures the minimum needed to act: requesting project, needed outcome, target date, and impact if missed. Then automatically route it to the owning team based on a simple rule (service/component owner, team directory, or manually selected owner).

Acceptance should be explicit: the owning team either accepts, rejects, or requests clarification. Avoid “soft” acceptance—make it a button that creates accountability and timestamps the decision.

When accepting, require a lightweight definition of done: deliverables (e.g., API endpoint, spec review, data export), acceptance test or verification step, and the sign-off owner on the requesting side.

This prevents the common failure mode where a dependency is “delivered” but not usable.

Changes are normal; surprises are not. Every change should:

Give users a clear at-risk flag with escalation levels (e.g., Team Lead → Program Lead → Exec Sponsor) and optional SLA expectations (response in X days, update every Y days). Escalation should be a workflow action, not an angry message thread.

Close a dependency only after two steps: delivery evidence (link, attachment, or note) and verification by the requester (or auto-close after a defined window). Capture a short retrospective field (“what blocked us?”) to improve future planning without running a full postmortem.

Dependency management breaks down quickly when people aren’t sure who can commit, who can edit, and who changed what. A clear permission model prevents accidental date changes, protects sensitive work, and builds trust across teams.

Start with a small set of roles and expand only when you hit real needs:

Implement permissions at the object level—dependencies, projects, milestones, comments/notes—and then by action:

A good default is least-privilege: new users should not be able to delete records or override commitments.

Not all projects should be equally visible. Add visibility scopes such as:

Define who can accept/reject requests and who can change committed dates—typically the receiving team lead (or delegate). Make the rule explicit in the UI: “Only the owning team can commit dates.”

Finally, add an audit log for key events: status changes, date edits, ownership changes, permission updates, and deletions (including who, when, and what changed). If you support SSO, pair it with the audit log to make access and accountability clear.

Alerts are where a dependency tool either becomes genuinely helpful—or turns into noise everyone learns to ignore. The goal is simple: keep work moving across teams by notifying the right people at the right time, with the right level of urgency.

Define the events that matter most for cross-functional dependencies:

Tie each trigger to an owner and a “next step,” so a notification isn’t just informational—it’s actionable.

Support multiple channels:

Keep it configurable at the user and team level. A dependency lead might want Slack pings; an exec sponsor might prefer a daily email summary.

Real-time messages are best for decisions (accept/reject) and escalations. Digests are better for awareness (upcoming due dates, “waiting on” items).

Include settings like: “immediate for assignments,” “daily digest for due dates,” and “weekly summary for health.” This reduces alert fatigue while still keeping dependencies visible.

Reminders should respect business days, time zones, and quiet hours. For example: send a reminder 3 business days before a due date, and never notify outside 9am–6pm local time.

Escalations should kick in when:

Escalate to the next responsible layer (team lead, program manager) and include context: what’s blocked, by whom, and what decision is needed.

Integrations make a dependency app useful on day one because most teams already track work elsewhere. The goal isn’t to “replace Jira” (or Linear, GitHub, Slack)—it’s to connect dependency decisions to the systems where execution happens.

Start with tools that represent work, time, and communication:

Choose 1–2 to pilot first. Too many integrations early can turn debugging into your main job.

Use a one-time CSV import to bootstrap existing dependencies, projects, and owners. Keep the format opinionated (e.g., dependency title, requester team, provider team, due date, status).

Then add ongoing sync only for the fields that must stay consistent (like external issue status or due date). This reduces surprise changes and makes troubleshooting easier.

Not every external field should be copied into your database.

A practical pattern is: store external IDs always, sync a small set of fields, and allow manual overrides only where your app is the source of truth.

Polling is simple but noisy. Prefer webhooks where possible:

When an event arrives, enqueue a background job to fetch the latest record via API and update your dependency object.

Write down which system owns each field:

Clear source-of-truth rules prevent “sync wars” and make governance and audits far simpler.

Dashboards are where your dependency app earns trust: leaders stop asking for “one more status slide,” and teams stop chasing updates across chat threads. The goal isn’t a wall of charts—it’s a fast way to answer, “What’s at risk, why, and who owns the next move?”

Start with a small set of risk flags that can be computed consistently:

These signals should be visible both at the dependency level and rolled up to project/program health.

Create views that match how steering meetings run:

A good default is a single page that answers: “What changed since last week?” (new risks, resolved blockers, date shifts).

Dashboards often need to leave the app. Add exports that preserve context:

When exporting, include owner, due dates, status, and the latest comment so the file stands on its own. That’s how dashboards replace manual status slides instead of creating another reporting task.

The goal isn’t to pick “the perfect” technology—it’s to choose a stack your team can build and operate confidently while keeping dependency views fast and trustworthy.

A practical baseline is:

This keeps the system easy to reason about: user actions are handled synchronously, while slow work (sending alerts, recalculating health metrics) happens asynchronously.

Dependency management is heavy on “find all items blocked by X” queries. A relational model works well for this, especially with the right indexes.

At minimum, plan for tables like Projects, Milestones/Deliverables, and Dependencies (from_id, to_id, type, status, due dates, owners). Add indexes for common filters (team, status, due date, project) and for traversals (from_id, to_id). This prevents the app from slowing down as the number of links grows.

Dependency graphs and Gantt-style timelines can get expensive. Choose rendering libraries that support virtualization (render only what’s visible) and incremental updates. Treat “show me everything” views as advanced modes, and default to scoped views (per project, per team, per date range).

Paginate lists by default, and cache common computed results (e.g., “blocked count per project”). For graphs, preload just the neighborhood around a selected node, then expand on demand.

Use separate environments (dev/staging/prod), add monitoring and error tracking, and log audit-relevant events. A dependency app quickly becomes a source of truth—downtime and silent failures cost real coordination time.

If your main goal is to validate workflows and UI quickly (inbox, acceptance, escalation, dashboards) before committing engineering bandwidth, you can prototype a dependency-management app in a vibe-coding platform like Koder.ai. It lets you iterate through the data model, roles/permissions, and key screens via chat, then export source code when you’re ready to productionize (commonly React on the web, Go + PostgreSQL on the backend). This can be especially useful for a pilot with 2–3 teams where speed of iteration matters more than perfect architecture on day one.

A dependency app only helps if people trust it. That trust is earned through careful testing, a contained pilot, and a rollout that doesn’t disrupt teams mid-delivery.

Start by validating the “happy path”: a team requests a dependency, the owning team accepts, work is delivered, and the dependency is closed with a clear outcome.

Then hit edge cases that often break real usage:

Dependency apps tend to fail when permissions are either too strict (people can’t do their job) or too loose (teams lose control).

Test scenarios like:

Alerts should make people act, not tune out.

Verify:

Before involving teams, preload realistic demo projects, milestones, and cross-team dependencies. Good seed data exposes confusing labels, missing statuses, and reporting gaps faster than synthetic test records.

Pilot with 2–3 teams that frequently depend on each other. Set a short window (2–4 weeks), collect feedback weekly, and iterate on:

Once the pilot teams say the tool saves time, roll out by grouping teams into waves and publishing a clear “how we work now” page (even a simple internal doc linked from the app’s header) so expectations stay consistent.

Start with a one-sentence problem statement you can repeat: dependencies are causing delays because ownership, timing, and status are unclear. Then pick a small set of measurable outcomes, such as:

If you can’t measure improvement, you can’t justify adoption.

Keep it tight and role-based:

Design your default views around “What do I owe?” and “What’s blocking me?” rather than around database objects.

Write a one-paragraph definition and stick to it. Common examples:

That definition determines your required fields, your workflow states, and how you report “done.”

A good minimal record captures who needs what, from whom, by when, plus traceability:

Avoid optional fields that stay empty; make the routing fields mandatory.

Use a simple, shared flow and make acceptance explicit:

Acceptance should be a deliberate action (button + timestamp), not implied in a comment thread. This is what creates accountability and clean reporting.

Pick granularity people already plan and report on:

If your milestones become too detailed, updates turn into busywork and data quality drops—push ticket-level detail back into Jira/Linear/etc.

Default to least-privilege and protect commitments:

This prevents accidental changes and reduces “who said what” debates.

Start with a small set of triggers that are genuinely actionable:

Offer real-time alerts for decisions and escalations, but use digests for awareness (daily/weekly). Add throttling to avoid “notification storms.”

Don’t try to replace execution tools. Use integrations to connect decisions to where work happens:

Write down source-of-truth rules (e.g., Jira owns issue status; your app owns acceptance and commitment dates).

Pilot with 2–3 teams that depend on each other for 2–4 weeks:

Only expand after pilot teams agree it saves time; roll out in waves with a clear “how we work now” doc linked from the app.