Jul 21, 2025·8 min

Building a Web App for Incident Impact Analysis, Step by Step

Learn how to design and build a web app that calculates incident impact using service dependencies, real-time signals, and clear dashboards for teams.

Define Incident Impact and the Decisions It Should Drive

Before you build calculations or dashboards, decide what “impact” actually means in your organization. If you skip this step, you’ll end up with a score that looks scientific but doesn’t help anyone act.

What counts as “impact” (and what doesn’t)

Impact is the measurable consequence of an incident on something the business cares about. Common dimensions include:

- Users: number of users unable to log in, error-rate spikes on key flows, degraded latency for a region.

- Revenue: checkouts failing, subscription renewals blocked, ad impressions dropping.

- SLA/SLO risk: minutes of downtime against an uptime target, error budget burn rate.

- Internal teams: support ticket volume, on-call load, blocked deploys.

Pick 2–4 primary dimensions and define them explicitly. For example: “Impact = affected paying customers + SLA minutes at risk,” not “Impact = anything that looks bad on graphs.”

Who uses the app, and what they need in the first 10 minutes

Different roles make different decisions:

- Incident commanders need a fast, defensible summary: what’s broken, who’s affected, and how it’s trending.

- Support needs customer-facing scope: which accounts, regions, or plans are impacted.

- Engineering needs a blast-radius hypothesis to guide debugging and mitigation.

- Executives need a concise business statement: severity, customer impact, and ETA confidence.

Design “impact” outputs so each audience can answer their top question without translating metrics.

Real-time vs. near-real-time: set expectations early

Decide what latency is acceptable. “Real-time” is expensive and often unnecessary; near-real-time (e.g., 1–5 minutes) may be enough for decision-making.

Write this down as a product requirement because it influences ingestion, caching, and UI.

Decisions the app should enable during an incident

Your MVP should directly support actions such as:

- Declare severity and escalation level

- Trigger customer communications (status page, support macros)

- Prioritize mitigation work (which service/team first)

- Decide on rollbacks, feature flags, or traffic shifts

- Identify which customers need proactive outreach

If a metric doesn’t change a decision, it’s probably not “impact”—it’s just telemetry.

Requirements Checklist: Inputs, Outputs, and Constraints

Before you design screens or pick a database, write down what “impact analysis” must answer during a real incident. The goal isn’t perfect precision on day one—it’s consistent, explainable results that responders can trust.

Required inputs (the minimum you need)

Start with the data you must ingest or reference to calculate impact:

- Incidents: ID, start/end times, status, owning team, summary, links to the incident channel/ticket.

- Services: canonical service list (name, owner, tier/criticality, runbook link).

- Dependencies: which services rely on which others (even if the first version is coarse).

- Telemetry signals: alerts, SLO burn rates, error rate/latency, deployment events—anything that indicates degradation.

- Customer accounts: account IDs, plan/SLA, region, key contacts, plus how accounts map to services (directly or via workloads).

Optional at launch (plan for it, don’t require it)

Most teams don’t have perfect dependency or customer mapping on day one. Decide what you’ll allow people to enter manually so the app is still useful:

- Manual selection of affected services/customers when data is missing

- Estimated start time or scope when telemetry is delayed

- Overrides with reasons (e.g., “false positive alert,” “internal-only impact”)

Design these as explicit fields (not ad-hoc notes) so they’re queryable later.

Key outputs (what the app must produce)

Your first release should reliably generate:

- Affected services and a clear “why” (signals + dependencies)

- Customer list with counts by plan/region and a “top accounts” view

- Severity/impact score that can be explained in plain language

- Timeline of when impact likely started, peaked, and recovered

- Optional but valuable: a cost estimate (SLA credits, support load, revenue risk) with confidence ranges

Non-functional constraints (what makes it trustworthy)

Impact analysis is a decision tool, so constraints matter:

- Latency: dashboards should load in seconds during an incident

- Uptime: treat it like internal critical tooling; define an availability target

- Auditability: log who changed an override, when, and what the previous value was

- Access control: restrict sensitive customer data; separate read vs. write permissions

Write these requirements as testable statements. If you can’t verify it, you can’t rely on it during an outage.

Data Model: Incidents, Services, Dependencies, and Customers

Your data model is the contract between ingestion, calculation, and the UI. If you get it right, you can swap tooling sources, refine scoring, and still answer the same questions: “What broke?”, “Who is affected?”, and “For how long?”

Core entities (keep them small and linkable)

At minimum, model these as first-class records:

- Incident: the narrative container (title, severity, status, owner), plus pointers to evidence.

- Service: the unit you map dependencies for (API, database, queue, third-party provider).

- Dependency: a directed edge service A → service B with metadata (type, criticality).

- Signal: a time-stamped observation (alert, SLO burn, error spike, synthetic check failure).

- Customer: an account or organization that consumes services.

- Subscription/SLA: what a customer is entitled to (plan, SLA/SLO targets, reporting rules).

Keep IDs stable and consistent across sources. If you already have a service catalog, treat it as the source of truth and map external tool identifiers into it.

Time modeling (impact is a time-window problem)

Store multiple timestamps on the incident to support reporting and analysis:

- start_time / end_time: actual impact window (can be refined later)

- detection_time: when you first knew

- mitigation_time: when fixes started reducing impact

Also store calculated time windows for impact scoring (e.g., 5-minute buckets). This makes replay and comparisons straightforward.

Relationships that power “who is affected?”

Model two key graphs:

- Service-to-service dependencies (blast radius)

- Customer-to-service usage (affected scope)

A simple pattern is customer_service_usage(customer_id, service_id, weight, last_seen_at) so you can rank impact by “how much the customer relies on it.”

Versioning and history (dependencies change)

Dependencies evolve, and impact calculations should reflect what was true at the time. Add effective dating to edges:

dependency(valid_from, valid_to)

Do the same for customer subscriptions and usage snapshots. With historical versions, you can accurately re-run past incidents during post-incident review and produce consistent SLA reporting.

Collecting and Normalizing Data from Your Tooling

Your impact analysis is only as good as the inputs feeding it. The goal here is straightforward: pull signals from the tools you already use, then convert them into a consistent event stream your app can reason about.

What to ingest (and why)

Start with a short list of sources that reliably describe “something changed” during an incident:

- Monitoring alerts (PagerDuty, Opsgenie, CloudWatch alarms): fast indicators of symptoms and severity

- Logs and traces (ELK, Datadog, OpenTelemetry backends): evidence of scope (which endpoints, which customers)

- Status page updates (Statuspage, Cachet): the official narrative and customer-facing timestamps

- Ticketing/incident tools (Jira, ServiceNow): ownership, timestamps, and post-incident data

Don’t try to ingest everything at once. Pick sources that cover detection, escalation, and confirmation.

Ingestion methods to choose from

Different tools support different integration patterns:

- Webhooks for near-real-time updates (best for alerts and status pages)

- Polling for APIs without webhooks (use backoff and rate limits)

- Batch imports for historical backfills (useful for initial validation)

- Manual entry for “last mile” corrections (an analyst can fix a missing service tag)

A practical approach is: webhooks for critical signals, plus batch imports to fill gaps.

Normalize into a common schema

Normalize every incoming item into a single “event” shape, even if the source calls it an alert, incident, or annotation. At minimum, standardize:

- Timestamp(s): occurred_at, detected_at, resolved_at (when available)

- Service identifiers: map source tags/names to your canonical service IDs

- Severity/priority: convert tool-specific levels into your scale

- Source and raw payload: keep the original JSON for audit and debugging

Data hygiene: duplicates, ordering, missing fields

Expect messy data. Use idempotency keys (source + external_id) to deduplicate, tolerate out-of-order events by sorting on occurred_at (not arrival time), and apply safe defaults when fields are missing (while flagging them for review).

A small “unmatched service” queue in the UI prevents silent errors and keeps your impact results trustworthy.

Mapping Service Dependencies for Accurate Blast Radius

Experiment without risk

Iterate on rules safely with snapshots and rollback when a change misbehaves.

If your dependency map is wrong, your blast radius will be wrong—even if your signals and scoring are perfect. The goal is to build a dependency graph you can trust during an incident and also afterward.

Start with a service catalog (your “source of truth”)

Before you map edges, define the nodes. Create a service catalog entry for every system you might reference in an incident: APIs, background workers, data stores, third-party vendors, and other critical shared components.

Each service should include at least: owner/team, tier/criticality (e.g., customer-facing vs. internal), SLA/SLO targets, and links to runbooks and on-call docs (for example, /runbooks/payments-timeouts).

Capture dependencies: static vs. learned

Use two complementary sources:

- Static (declared) dependencies: what teams say they depend on (from IaC, config, service manifests, ADRs). Stable and easy to audit.

- Learned (observed) dependencies: what your systems actually call (from traces, service mesh telemetry, API gateway logs, egress proxies, database audit logs). These catch “unknown unknowns,” like a forgotten downstream call.

Treat these as separate edge types so people can understand confidence: “declared by team” vs. “observed in last 7 days.”

Directionality and criticality matter

Dependencies should be directional: Checkout → Payments is not the same as Payments → Checkout. Direction drives reasoning (“if Payments is degraded, which upstreams might fail?”).

Also model hard vs. soft dependencies:

- Hard: failure blocks core functionality (auth service for login).

- Soft: degradation reduces quality but has a fallback (recommendations, optional enrichment).

This distinction prevents overstating impact and helps responders prioritize.

Snapshot the graph for replay and post-incident analysis

Your architecture changes weekly. If you don’t store snapshots, you can’t accurately analyze an incident from two months ago.

Persist dependency graph versions over time (daily, per deploy, or on change). When calculating blast radius, resolve the incident timestamp to the closest graph snapshot, so “who was affected” reflects reality at that moment—not today’s architecture.

Impact Calculation: From Signals to Scores and Affected Scope

Once you’re ingesting signals (alerts, SLO burn, synthetic checks, customer tickets), the app needs a consistent way to turn messy inputs into a clear statement: what is broken, how bad is it, and who is affected?

Pick a scoring approach (start simple)

You can get to a usable MVP with any of these patterns:

- Rule-based scoring: “If checkout error rate > 5% for 10 minutes, impact = High.” Easy to explain and debug.

- Weighted formula: Combine normalized metrics into a single score (e.g., 0–100). Useful when you have many signals and want a smooth curve.

- Tier-based mapping: Map systems to business tiers (Tier 0–3) and cap or boost severity based on tier. This keeps outcomes aligned with business priorities.

Whichever approach you choose, store the intermediate values (threshold hit, weights, tier) so people can understand why the score happened.

Define impact dimensions

Avoid collapsing everything into one number too early. Track a few dimensions separately, then derive an overall severity:

- Availability: downtime, failed requests, unreachable endpoints

- Latency: p95/p99 degradation against a baseline or SLO

- Errors: error rate spikes, failed jobs, timeouts

- Data correctness: missing/incorrect records, delayed processing

- Security risk: suspicious access patterns, data exposure indicators

This helps responders communicate precisely (e.g., “available but slow” vs. “incorrect results”).

Compute affected scope (customers/users)

Impact isn’t only service health—it’s who felt it.

Use usage mapping (tenant → service, customer plan → features, user traffic → endpoint) and calculate affected customers within a time window aligned to the incident (start time, mitigation time, and any backfill period).

Be explicit about assumptions: sampled logs, estimated traffic, or partial telemetry.

Manual adjustments—with accountability

Operators will need to override: a false-positive alert, a partial rollout, a known subset of tenants.

Allow manual edits to severity, dimensions, and affected customers, but require:

- Who changed what

- When

- Why (short reason + optional link to ticket/runbook)

This audit trail protects trust in the dashboard and makes post-incident review faster.

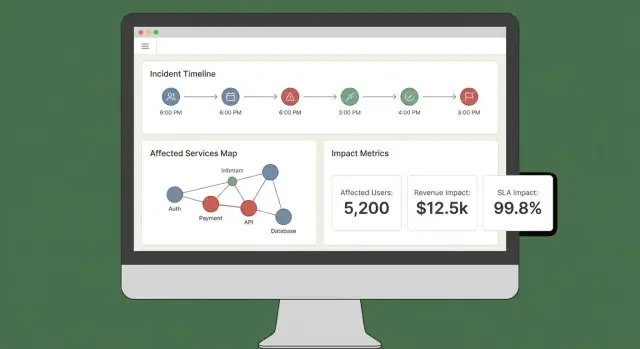

UX and Dashboards: Make Impact Understandable in Minutes

A good impact dashboard answers three questions quickly: What’s affected? Who’s affected? How sure are we? If users have to open five tabs to piece that together, they won’t trust the output—or act on it.

Core views to ship in the MVP

Start with a small set of “always-there” views that map to real incident workflows:

- Incident overview: status, start time, current impact score, top affected services/customers, and the most recent evidence.

- Affected services: a ranked list showing severity, region, and the dependency path (so engineers can spot where to intervene).

- Affected customers: counts and named accounts by tier/plan, plus estimated user impact if you track it.

- Timeline: a single chronological stream combining detections, deploys, alerts, mitigations, and impact changes.

- Actions: suggested next steps, owners, and links to playbooks or tickets.

Make the “why” visible

Impact scores without explanation feel arbitrary. Every score should be traceable back to inputs and rules:

- Show which signals contributed (errors, latency, health checks, support volume) and their current values.

- Display rules and thresholds used (e.g., “latency p95 > 2s for 10 min = degraded”).

- Add a lightweight confidence indicator (e.g., “High confidence: confirmed by 3 sources”).

A simple “Explain impact” drawer or panel can do this without cluttering the main view.

Filters and drilldowns that match real questions

Make it easy to slice impact by service, region, customer tier, and time range. Let users click any chart point or row to drill into raw evidence (the exact monitors, logs, or events that drove the change).

Sharing and exports

During an active incident, people need portable updates. Include:

- Shareable links to the incident view (respecting permissions)

- CSV export for service/customer lists

- PDF export for status updates and post-incident summaries

If you already have a status page, link to it via a relative route like /status so comms teams can cross-reference quickly.

Security, Permissions, and Audit Logging

Test impact scoring ideas

Prototype your incident data model and scoring rules before you commit to a full build.

Impact analysis is only useful if people trust it—which means controlling who can see what and keeping a clear record of changes.

Roles and permissions (start simple)

Define a small set of roles that match how incidents run in real life:

- Viewer: read-only access to incident summaries and high-level impact.

- Responder: can add notes, confirm affected services, and update operational fields.

- Incident commander: can approve impact overrides, set customer-facing status, and close incidents.

- Admin: manages integrations, role assignments, and data retention.

Keep permissions aligned to actions, not job titles. For example, “can export customer impact report” is a permission you can grant to commanders and a small subset of admins.

Protect sensitive customer data

Incident impact analysis often touches customer identifiers, contract tiers, and sometimes contact details. Apply least privilege by default:

- Mask sensitive fields (e.g., show the last 4 characters of an account ID) unless the user has explicit access.

- Separate “who is impacted” from “what is broken.” Many users only need service-level impact, not customer-level lists.

- Secure exports: watermark PDFs/CSVs, include the requesting user, and restrict exports to approved roles. Prefer short-lived, signed download links.

Audit logging that answers “who changed what?”

Log key actions with enough context to support reviews:

- Manual edits to impact inputs (affected services/customers)

- Impact score overrides (old value, new value, reason)

- Acknowledgments and status transitions

- Report generation and exports

Store audit logs append-only, with timestamps and actor identity. Make them searchable per incident so they’re usable during a post-incident review.

Plan for compliance needs (without overpromising)

Document what you can support now—retention period, access controls, encryption, and audit coverage—and what’s on the roadmap.

A short “Security & Audit” page in your app (e.g., /security) helps set expectations and reduces ad-hoc questions during critical incidents.

Workflows and Notifications During an Active Incident

Impact analysis only matters during an incident if it drives the next action. Your app should behave like a “co-pilot” for the incident channel: it turns incoming signals into clear updates, and it nudges people when the impact meaningfully changes.

Connect to chat and incident channels

Start by integrating with the place responders already work (often Slack, Microsoft Teams, or a dedicated incident tool). The goal isn’t to replace the channel—it’s to post context-aware updates and keep a shared record.

A practical pattern is to treat the incident channel as both an input and an output:

- Input: responders tag the app (e.g., “/impact summarize”, “/impact add affected customer Acme”) to correct or enrich scope.

- Output: the app posts concise, consistent updates (current impact score, affected services/customers, trend vs. last update).

If you’re prototyping quickly, consider building the workflow end-to-end first (incident view → summarize → notify) before perfecting scoring. Platforms like Koder.ai can be useful here: you can iterate on a React dashboard and a Go/PostgreSQL backend through a chat-driven workflow, then export the source code once the incident team agrees the UX matches reality.

Threshold-based notifications (not noise)

Avoid alert spam by triggering notifications only when impact crosses explicit thresholds. Common triggers include:

- Scope: affected customers count jumps (e.g., 10 → 100)

- Tier: a Tier 1 service becomes affected

- Revenue / SLA risk: projected SLA breach or high contract value involved

- Blast radius expansion: new dependent services join the affected set

When a threshold is crossed, send a message that explains why (what changed), who should act, and what to do next.

Link to runbooks and workflows

Every notification should include “next-step” links so responders can move quickly:

- Runbooks: /blog/incident-runbook-template

- Escalation policy: /pricing

- Service ownership page: /services/payments

Keep these links stable and relative so they work across environments.

Stakeholder updates: internal and customer-facing

Build two summary formats from the same data:

- Internal update: technical detail, suspected cause, mitigation progress, ETA confidence.

- Customer-facing update: plain language, current user impact, workarounds, next update time.

Support scheduled summaries (e.g., every 15–30 minutes) and on-demand “generate update” actions, with an approval step before sending externally.

Validation: Testing, Replay, and Accuracy Checks

Generate the full stack

Spin up a React UI with a Go API and PostgreSQL schema based on your incident workflow.

Impact analysis is only useful if people trust it during an incident and after. Validation should prove two things: (1) the system produces stable, explainable results, and (2) those results match what your organization later agrees actually happened.

Testing strategy: rules and pipelines

Start with automated tests that cover the two most failure-prone areas: scoring logic and data ingestion.

- Unit tests for scoring rules: Treat each rule as a contract. Given specific signals (error rate, latency, synthetic checks, ticket volume), your test should assert the expected impact score and affected scope. Include boundary tests (just under/over thresholds) so metric jitter doesn’t flip outcomes unexpectedly.

- Integration tests for ingestion: Validate the full path from webhook/event input to normalized records and computed impact. Use recorded payloads from your observability and incident tools to catch schema drift early.

Keep test fixtures readable: when someone changes a rule, they should be able to understand why a score changed.

Replay past incidents to validate outputs

A replay mode is a fast path to confidence. Run historical incidents through the app and compare what the system would have shown “in the moment” versus what responders concluded later.

Practical tips:

- Reconstruct timelines using event timestamps (not ingestion time) to reflect reality.

- Freeze dependency graphs as-of the incident date if your service catalog has changed.

- Store replay results so you can compare versions after rule tweaks.

Handle edge cases that break naive scoring

Real incidents rarely look like clean outages. Your validation suite should include scenarios like:

- Partial outages (some endpoints or customer segments failing)

- Degraded performance (slow but not failing) where business impact can still be high

- Multi-region failures where the same service has different health per region

For each, assert not only the score, but also the explanation: which signals and which dependencies/customers drove the result.

Measuring accuracy against post-incident findings

Define accuracy in operational terms, then track it.

Compare computed impact to post-incident review outcomes: affected services, duration, customer count, SLA breach, and severity. Log discrepancies as validation issues with a category (missing data, wrong dependency, bad threshold, delayed signal).

Over time, the goal isn’t perfection—it’s fewer surprises and faster agreement during incidents.

Deployment, Scaling, and Iterating After the MVP

Shipping an MVP for incident impact analysis is mostly about reliability and feedback loops. Your first deployment choice should optimize for speed of change, not theoretical future scale.

Pick a deployment style you can evolve

Start with a modular monolith unless you already have a strong platform team and clear service boundaries. One deployable unit simplifies migrations, debugging, and end-to-end testing.

Split into services only when you feel real pain:

- the ingestion pipeline needs independent scaling

- multiple teams need to deploy independently

- failure domains are hard to reason about in a single app

A pragmatic middle ground is one app + background workers (queues) + a separate ingestion edge if needed.

If you want to move fast without committing to a large bespoke platform build up front, Koder.ai can help accelerate the MVP: its chat-driven “vibe-coding” workflow is well-suited to building a React UI, a Go API, and a PostgreSQL data model, with snapshots/rollback when you’re iterating on scoring rules and workflow changes.

Choose storage based on access patterns

Use relational storage (Postgres/MySQL) for core entities: incidents, services, customers, ownership, and calculated impact snapshots. It’s easy to query, audit, and evolve.

For high-volume signals (metrics, logs-derived events), add a time-series store (or columnar store) when raw signal retention and rollups become expensive in SQL.

Consider a graph database only if dependency queries become a bottleneck or your dependency model becomes highly dynamic. Many teams can get far with adjacency tables plus caching.

Add observability for the app itself

Your impact analysis app becomes part of your incident toolchain, so instrument it like production software:

- error rate and slow endpoints (especially “recalculate impact”)

- worker queue depth/lag and retry rates

- ingestion throughput and failure counts per source

- data freshness (time since last successful pull/push)

- calculation duration and cache hit rate

Expose a “health + freshness” view in the UI so responders can trust (or question) the numbers.

Plan iterations and refactors deliberately

Define MVP scope tightly: a small set of tools to ingest, a clear impact score, and a dashboard that answers “who is affected and how much.” Then iterate:

- Next features: better dependency accuracy, customer-specific weighting, SLA reporting exports, replay for past incidents

- Refactor triggers: you’re adding special cases weekly, recalculation is too slow, or the data model can’t express reality without hacks

Treat the model as a product: version it, migrate it safely, and document changes for post-incident review.

FAQ

What is “incident impact” in this context?

Impact is the measurable consequence of an incident on business-critical outcomes.

A practical definition names 2–4 primary dimensions (e.g., affected paying customers + SLA minutes at risk) and explicitly excludes “anything that looks bad on graphs.” That keeps the output tied to decisions, not just telemetry.

Which impact dimensions should we track first?

Pick dimensions that map to actions your teams take during the first 10 minutes.

Common MVP-friendly dimensions:

- Users/customers affected (counts, tiers, regions)

- Revenue risk (checkout failures, renewal blocks)

- SLA/SLO risk (downtime minutes, error budget burn)

- Internal load (support volume, blocked deploys)

Limit it to 2–4 so the score stays explainable.

Who are the main users of an impact analysis app, and what do they need?

Design outputs so each role can answer their main question without translating metrics:

- Incident commander: a fast summary (what’s broken, who’s affected, trend)

- Support: affected accounts/regions/plans and wording-ready scope

- Engineering: blast radius hypothesis and evidence to guide mitigation

- Executives: severity, business impact, and ETA confidence

If one metric can’t be used by any of these audiences, it’s likely not “impact.”

How should we set expectations for real-time vs. near-real-time impact data?

“Real-time” is expensive; many teams do fine with near-real-time (1–5 minutes).

Write a latency target as a requirement because it affects:

- ingestion method (webhooks vs polling)

- caching strategy

- how confident you can be in “current” numbers

Also set expectations in the UI (e.g., “data fresh as of 2 minutes ago”).

What decisions should the MVP impact dashboard enable during an incident?

Start by listing the decisions responders must make, then ensure each output supports one:

- declare severity and escalation level

- trigger customer communications (status page, support macros)

- prioritize mitigation (which service/team first)

- decide rollbacks/feature flags/traffic shifts

- identify customers needing proactive outreach

If a metric doesn’t change a decision, keep it as telemetry, not impact.

What are the minimum required inputs to calculate incident impact?

Minimum required inputs typically include:

- Incidents: ID, start/end, status, owner, links

- Services: canonical catalog (owner, tier, runbooks)

- Dependencies: service-to-service edges (even coarse at first)

- alerts, SLO burn, errors/latency, deploy events

How do we handle missing data or incorrect signals early on?

Allow explicit, queryable manual fields so the app remains useful when data is missing:

- select affected services/customers manually

- estimate start time or scope when telemetry is delayed

- apply overrides with reasons (e.g., false positive, internal-only impact)

Require who/when/why for changes so trust doesn’t degrade over time.

What outputs should the first release generate?

A reliable MVP should produce:

- ranked affected services with a clear “why” (signals + dependency path)

- an affected customer list with counts by plan/region and “top accounts”

- a severity/impact score that can be explained in plain language

- an impact timeline (start, peak, recovery)

Optionally add cost estimates (SLA credits, revenue risk) with confidence ranges.

How do we collect and normalize data from existing tools?

Normalize every source into one event schema so calculations stay consistent.

At minimum standardize:

- timestamps:

occurred_at,detected_at,

What’s a good approach to impact scoring and affected scope calculation?

Start simple and explainable:

- Rule-based: clear thresholds (easy to debug)

- Weighted formula (0–100): smooth scoring across many signals

- Tier-based mapping: align outcomes with business criticality

Keep intermediate values (threshold hits, weights, tier, confidence) so users can see why the score changed. Track dimensions (availability/latency/errors/data correctness/security) before collapsing into one number.