May 13, 2025·8 min

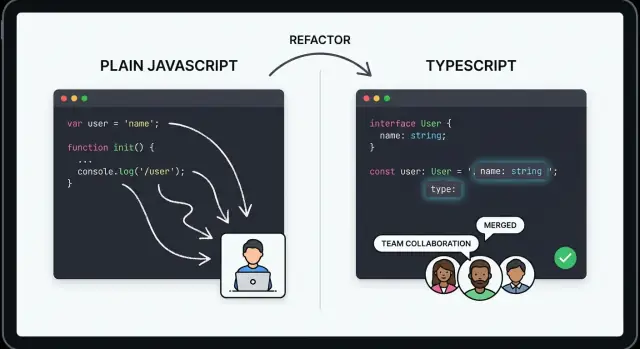

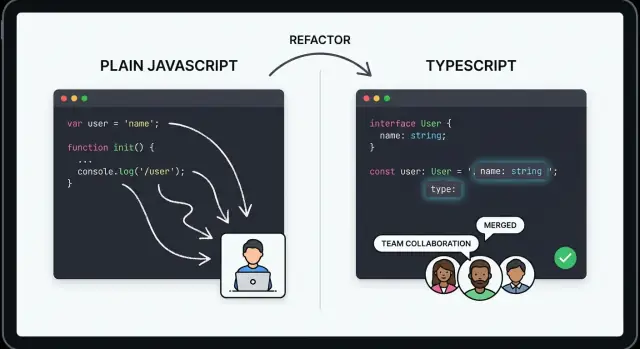

How TypeScript Made Large JavaScript Frontends Maintainable

TypeScript added types, better tooling, and safer refactors—helping teams scale JavaScript frontends with fewer bugs and clearer code.

TypeScript added types, better tooling, and safer refactors—helping teams scale JavaScript frontends with fewer bugs and clearer code.

A frontend that started as “just a few pages” can quietly grow into thousands of files, dozens of feature areas, and multiple teams shipping changes every day. At that size, JavaScript’s flexibility stops feeling like freedom and starts feeling like uncertainty.

In a large JavaScript app, many bugs don’t show up where they were introduced. A small change in one module can break a distant screen because the connection between them is informal: a function expects a certain shape of data, a component assumes a prop is always present, or a helper returns different types depending on input.

Common pain points include:

Maintainability isn’t a vague “code quality” score. For teams, it usually means:

TypeScript is JavaScript + types. It doesn’t replace the web platform or require a new runtime; it adds a compile-time layer that describes data shapes and API contracts.

That said, TypeScript isn’t magic. It adds some upfront effort (types to define, occasional friction with dynamic patterns). But it helps most where large frontends suffer: at module boundaries, in shared utilities, in data-heavy UI, and during refactors where “I think this is safe” needs to become “I know this is safe.”

TypeScript didn’t replace JavaScript so much as extend it with something teams had wanted for years: a way to describe what code is supposed to accept and return, without giving up the language and ecosystem they already used.

As frontends became full applications, they accumulated more moving parts: large single-page apps, shared component libraries, multiple API integrations, complex state management, and build pipelines. In a small codebase you can “keep it in your head.” In a large one, you need faster ways to answer questions like: What shape is this data? Who calls this function? What breaks if I change this prop?

Teams adopted TypeScript because it didn’t demand a clean-slate rewrite. It works with npm packages, familiar bundlers, and common testing setups, while compiling down to plain JavaScript. That made it easier to introduce incrementally, repo by repo or folder by folder.

“Gradual typing” means you can add types where they provide the most value and keep other areas loosely typed for now. You can start with minimal annotations, allow JavaScript files, and improve coverage over time—getting better editor autocomplete and safer refactors without needing perfection on day one.

Large frontends are really collections of small agreements: a component expects certain props, a function expects certain arguments, and API data should have a predictable shape. TypeScript makes those agreements explicit by turning them into types—a kind of living contract that stays close to the code and evolves with it.

A type says, “this is what you must provide, and this is what you’ll get back.” That applies equally to tiny helpers and big UI components.

type User = { id: string; name: string };

function formatUser(user: User): string {

return `${user.name} (#${user.id})`;

}

type UserCardProps = { user: User; onSelect: (id: string) => void };

With these definitions, anyone calling formatUser or rendering UserCard can immediately see the expected shape without reading the implementation. This improves readability, especially for new team members who don’t yet know where “the real rules” live.

In plain JavaScript, a typo like user.nmae or passing the wrong argument type often makes it to runtime and fails only when that code path runs. With TypeScript, the editor and compiler flag issues early:

user.fullName when only name existsonSelect(user) instead of onSelect(user.id)These are small errors, but in a large codebase they create hours of debugging and testing churn.

TypeScript’s checks happen while you build and edit your code. It can tell you “this call doesn’t match the contract” without executing anything.

What it does not do is validate data at runtime. If an API returns something unexpected, TypeScript won’t stop the server response. Instead, it helps you write code that assumes a clear shape—and it nudges you toward runtime validation where it’s genuinely needed.

The result is a codebase where boundaries are clearer: contracts are documented in types, mismatches are caught early, and new contributors can safely change code without guessing what other parts expect.

TypeScript doesn’t just catch mistakes at build time—it turns your editor into a map of the codebase. When a repo grows to hundreds of components and utilities, maintainability often fails not because the code is “wrong,” but because people can’t quickly answer simple questions: What does this function expect? Where is it used? What will break if I change it?

With TypeScript, autocomplete becomes more than a convenience. When you type a function call or a component prop, the editor can suggest valid options based on actual types, not guesses. That means fewer trips to search results and fewer “what was this called again?” moments.

You also get inline documentation: parameter names, optional vs required fields, and JSDoc comments surfaced right where you’re working. In practice, it reduces the need to open extra files just to understand how to use a piece of code.

In large repos, time is often lost to manual searching—grep, scrolling, opening multiple tabs. Type information makes navigation features far more accurate:

This changes day-to-day work: instead of holding the whole system in your head, you can follow a reliable trail through the code.

Types make intent visible during review. A diff that adds userId: string or returns Promise<Result<Order, ApiError>> communicates constraints and expectations without long explanations in comments.

Reviewers can focus on behavior and edge cases rather than debating what a value “should” be.

Many teams use VS Code because it has strong TypeScript support out of the box, but you don’t need a specific editor to benefit. Any environment that understands TypeScript can provide the same class of navigation and hinting features.

If you want to formalize these benefits, teams often pair them with lightweight conventions in /blog/code-style-guidelines so the tooling stays consistent across the project.

Refactoring a large frontend used to feel like walking through a room full of tripwires: you could improve one area, but you never knew what would break two screens away. TypeScript changes that by turning many risky edits into controlled, mechanical steps. When you change a type, the compiler and your editor show you every place that depends on it.

TypeScript makes refactors safer because it forces the codebase to stay consistent with the “shape” you declare. Instead of relying on memory or a best-effort search, you get a precise list of affected call sites.

A few common examples:

Button used to accept isPrimary and you rename it to variant, TypeScript will flag every component that still passes isPrimary.user.name becomes user.fullName, the type update surfaces all the reads and assumptions across the app.The most practical benefit is speed: after a change, you run the type checker (or just watch your IDE) and follow the errors like a checklist. You’re not guessing which view might be affected—you’re fixing every place the compiler can prove is incompatible.

TypeScript doesn’t catch every bug. It can’t guarantee that the server actually sends the data it promised, or that a value isn’t null in a surprising edge case. User input, network responses, and third-party scripts still require runtime validation and defensive UI states.

The win is that TypeScript removes a huge class of “accidental breakage” during refactors, so the remaining bugs are more often about real behavior—not missed rename fallout.

APIs are where many frontend bugs begin—not because teams are careless, but because real responses drift over time: fields get added, renamed, made optional, or temporarily missing. TypeScript helps by making the shape of data explicit at every handoff, so a change in an endpoint is more likely to show up as a compile-time error than as a production exception.

When you type an API response (even roughly), you force the app to agree on what “a user”, “an order”, or “a search result” actually looks like. That clarity spreads quickly:

A common pattern is to type the boundary where data enters the app (your fetch layer), then pass typed objects onward.

Production APIs often include:

null used intentionally)TypeScript makes you handle these cases deliberately. If user.avatarUrl might be missing, the UI must provide a fallback, or the mapping layer must normalize it. This pushes “what do we do when it’s absent?” decisions into code review, instead of leaving them to chance.

TypeScript checks happen at build time, but API data arrives at runtime. That’s why runtime validation can still be useful—especially for untrusted or changing APIs. A practical approach:

Teams can hand-write types, but you can also generate them from OpenAPI or GraphQL schemas. Generation reduces manual drift, yet it’s not mandatory—many projects start with a few hand-authored response types and adopt generation later if it pays off.

UI components are supposed to be small, reusable building blocks—but in large apps they often turn into fragile “mini-apps” with dozens of props, conditional rendering, and subtle assumptions about what data looks like. TypeScript helps keep these components maintainable by making those assumptions explicit.

In any modern UI framework, components receive inputs (props/inputs) and manage internal data (state). When those shapes are untyped, you can accidentally pass the wrong value and only discover it at runtime—sometimes only on a rarely used screen.

With TypeScript, props and state become contracts:

These guardrails reduce the amount of defensive code (“if (x) …”) and make component behavior easier to reason about.

A common source of bugs in large codebases is prop mismatch: the parent thinks it’s passing userId, the child expects id; or a value is sometimes a string and sometimes a number. TypeScript surfaces these issues immediately, where the component is used.

Types also help model valid UI states. Instead of representing a request as loosely related booleans like isLoading, hasError, and data, you can use a discriminated union such as { status: 'loading' | 'error' | 'success' } with the appropriate fields for each case. This makes it much harder to render an error view without an error message, or a success view without data.

TypeScript integrates well across the major ecosystems. Whether you build components with React function components, Vue’s Composition API, or Angular’s class-based components and templates, the core benefit is the same: typed inputs and predictable component contracts that tools can understand.

In a shared component library, TypeScript definitions act like up-to-date documentation for every consuming team. Autocomplete shows available props, inline hints explain what they do, and breaking changes become visible during upgrades.

Instead of relying on a wiki page that drifts over time, the “source of truth” travels with the component—making reuse safer and reducing the support burden on the library maintainers.

Large frontend projects rarely fail because one person wrote “bad code.” They become painful when many people make reasonable choices in slightly different ways—different naming, different data shapes, different error handling—until the app feels inconsistent and hard to predict.

In multi-team or multi-repo environments, you can’t rely on everyone remembering unwritten rules. People rotate, contractors join, services evolve, and “the way we do it here” turns into tribal knowledge.

TypeScript helps by making expectations explicit. Instead of documenting what a function should accept or return, you encode it in types that every caller must satisfy. That turns consistency into the default behavior rather than a guideline that’s easy to miss.

A good type is a small agreement the whole team shares:

User always has id: string, not sometimes number.When these rules live in types, new teammates can learn by reading code and using IDE hints, not by asking in Slack or finding a senior engineer.

TypeScript and linters solve different problems:

Used together, they make PRs about behavior and design—not bikeshedding.

Types can become noise if they’re over-engineered. A few practical rules keep them approachable:

type OrderStatus = ...) over deeply nested generics.unknown + narrow intentionally instead of sprinkling any.Readable types act like good documentation: precise, current, and easy to follow.

Migrating a large frontend from JavaScript to TypeScript works best when it’s treated as a series of small, reversible steps—not a one-time rewrite. The goal is to increase safety and clarity without freezing product work.

1) “New files first”

Start writing all new code in TypeScript while leaving existing modules alone. This stops the codebase from growing its JavaScript surface area and lets the team learn gradually.

2) Module-by-module conversion

Pick one boundary at a time (a feature folder, a shared utility package, or a UI component library) and convert it completely. Prioritize modules that are widely used or frequently changed—those yield the biggest payback.

3) Strictness steps

Even after switching file extensions, you can move toward stronger guarantees in stages. Many teams begin permissive and tighten rules over time as types become more complete.

Your tsconfig.json is the migration steering wheel. A practical pattern is:

strict mode later (or enable strict flags one by one).This avoids a huge initial backlog of type errors and keeps the team focused on changes that matter.

Not every dependency ships good typings. Typical options:

@types/...).any contained to a small adapter layer.Rule of thumb: don’t block the migration waiting for perfect types—create a safe boundary and move on.

Set small milestones (e.g., “convert shared utilities,” “type the API client,” “strict in /components”) and define simple team rules: where TypeScript is required, how to type new APIs, and when any is allowed. That clarity keeps progress steady while features continue shipping.

If your team is also modernizing how you build and ship apps, a platform like Koder.ai can help you move faster during these transitions: you can scaffold React + TypeScript frontends and Go + PostgreSQL backends via a chat-based workflow, iterate in a “planning mode” before generating changes, and export the source code when you’re ready to bring it into your repo. Used well, that complements TypeScript’s goal: reduce uncertainty while keeping delivery speed high.

TypeScript makes large frontends easier to change, but it’s not a free upgrade. Teams usually feel the cost most during adoption and during periods of heavy product change.

The learning curve is real—especially for developers new to generics, unions, and narrowing. Early on, it can feel like you’re “fighting the compiler,” and type errors show up exactly when you’re trying to move fast.

You’ll also add build complexity. Type-checking, transpilation, and sometimes separate configs for tooling (bundler, tests, linting) introduce more moving parts. CI can get slower if type checking isn’t tuned.

TypeScript can become a drag when teams over-type everything. Writing extremely detailed types for short-lived code or internal scripts often costs more than it saves.

Another common slowdown is unclear generics. If a utility’s type signature is too clever, the next person can’t understand it, autocomplete gets noisy, and simple changes turn into “type puzzle solving.” That’s a maintainability problem, not a win.

Pragmatic teams treat types as a tool, not a goal. Useful guidelines:

unknown (with runtime checks) when data is untrusted, rather than forcing it into any.any, @ts-expect-error) sparingly, with comments explaining why and when to remove them.A common misconception: “TypeScript prevents bugs.” It prevents a category of bugs, mostly around incorrect assumptions in code. It does not stop runtime failures like network timeouts, invalid API payloads, or JSON.parse throwing.

It also doesn’t improve runtime performance by itself. TypeScript types are erased at build time; any speed-up you feel usually comes from better refactoring and fewer regressions, not faster execution.

Large TypeScript frontends stay maintainable when teams treat types as part of the product—not an optional layer you sprinkle on later. Use this checklist to spot what’s working and what’s quietly adding friction.

"strict": true (or a documented plan to get there). If you can’t, enable strict options incrementally (for example noImplicitAny, then strictNullChecks)./types or /domain folder), and make “one source of truth” real—generated types from OpenAPI/GraphQL are even better.Prefer small modules with clear boundaries. If a file has both data fetching, transformation, and UI logic, it becomes hard to change safely.

Use meaningful types instead of clever ones. For example, explicit UserId and OrderId aliases can prevent mix-ups, and narrow unions ("loading" | "ready" | "error") make state machines readable.

any spreading through the codebase, especially in shared utilities.as Something) to silence errors instead of modeling reality.User shapes in different folders), which guarantees drift.TypeScript is usually worth it for multi-person teams, long-lived products, and apps that refactor often. Plain JavaScript can be fine for small prototypes, short-lived marketing sites, or very stable code where the team moves faster with minimal tooling—as long as you’re honest about the trade-off and keep the scope contained.

TypeScript adds compile-time types that make assumptions explicit at module boundaries (function inputs/outputs, component props, shared utilities). In large codebases, that turns “it runs” into enforceable contracts, catching mismatches during editing/build instead of in QA or production.

No. TypeScript types are erased at build time, so they don’t validate API payloads, user input, or third-party script behavior by themselves.

Use TypeScript for developer-time safety, and add runtime validation (or defensive UI states) where data is untrusted or failures must be handled gracefully.

A “living contract” is a type that describes what must be provided and what will be returned.

Examples:

User, Order, Result)Because these contracts live next to code and are checked automatically, they stay more accurate than docs that drift.

It catches issues like:

user.fullName when only name exists)These are common “accidental breakage” problems that otherwise show up only when a specific path is executed.

Type information makes editor features accurate:

This reduces the time spent hunting through files just to understand how to use code.

When you change a type (like a prop name or response model), the compiler can point to every incompatible call site.

A practical workflow is:

This turns many refactors into mechanical, trackable steps rather than guesswork.

Type your API boundary (fetch/client layer) so everything downstream works with a predictable shape.

Common practices:

null/missing fields to defaults)For high-risk endpoints, add runtime validation in the boundary layer and keep the rest of the app purely typed.

Typed props and state make assumptions explicit and harder to misuse.

Examples of practical wins:

loading | error | success)This reduces fragile components that rely on “implicit rules” scattered across the repo.

A common migration plan is incremental:

For untyped dependencies, install packages or create small local type declarations to contain to an adapter layer.

Common trade-offs include:

Avoid the most common self-inflicted slowdown: over-engineered types. Prefer readable, named types; use unknown plus narrowing for untrusted data; and limit escape hatches like any or with clear justification.

@typesany@ts-expect-error