Apr 23, 2025·8 min

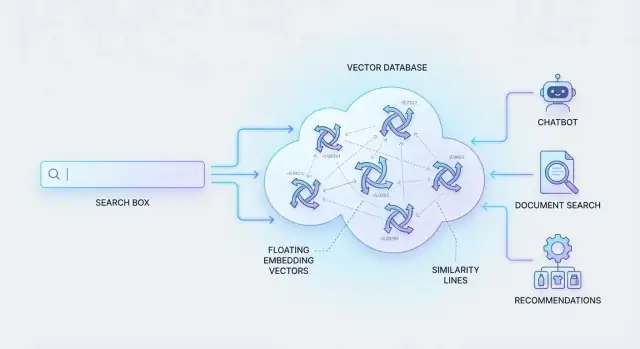

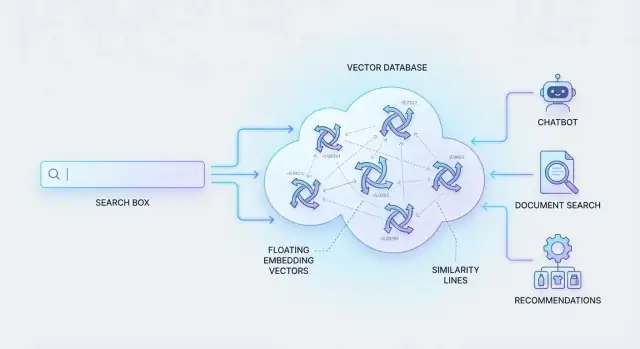

How Vector Databases Power Semantic Search for AI Apps

Learn how vector databases store embeddings, run fast similarity search, and support semantic search, RAG chatbots, recommendations, and other AI apps.

Learn how vector databases store embeddings, run fast similarity search, and support semantic search, RAG chatbots, recommendations, and other AI apps.

Semantic search is a way of searching that focuses on what you mean, not just the exact words you type.

If you’ve ever searched for something and thought, “the answer is clearly in here—why can’t it find it?”, you’ve felt the limits of keyword search. Traditional search matches terms. That works when the wording in your query and the wording in the content overlap.

Keyword search struggles with:

It can also overvalue repeated words, returning results that look relevant on the surface while ignoring the page that actually answers the question using different wording.

Imagine a help center with an article titled “Pause or cancel your subscription.” A user searches:

“stop my payments next month”

A keyword system might not rank that article highly if it doesn’t contain “stop” or “payments.” Semantic search is designed to understand that “stop my payments” is closely related to “cancel subscription,” and bring that article to the top—because the meaning aligns.

To make this work, systems represent content and queries as “meaning fingerprints” (numbers that capture similarity). Then they need to search through millions of these fingerprints quickly.

That’s what vector databases are built for: storing these numeric representations and retrieving the most similar matches efficiently, so semantic search feels instant even at large scale.

An embedding is a numeric representation of meaning. Instead of describing a document with keywords, you represent it as a list of numbers (a “vector”) that captures what the content is about. Two pieces of content that mean similar things end up with vectors that sit near each other in that numeric space.

Think of an embedding as a coordinate on a very high-dimensional map. You usually won’t read the numbers directly—they’re not meant to be human-friendly. Their value is in how they behave: if “cancel my subscription” and “how do I stop my plan?” produce nearby vectors, a system can treat them as related even when they share few (or zero) words.

Embeddings aren’t limited to text.

This is how a single vector database can support “search with an image,” “find similar songs,” or “recommend products like this.”

Vectors don’t come from manual tagging. They’re produced by machine learning models trained to compress meaning into numbers. You send content to an embedding model (hosted by you or a provider), and it returns a vector. Your app stores that vector alongside the original content and metadata.

The embedding model you pick strongly influences results. Larger or more specialized models often improve relevance but cost more (and may be slower). Smaller models can be cheaper and faster, but may miss nuance—especially for domain-specific language, multiple languages, or short queries. Many teams test a few models early to find the best trade-off before scaling.

A vector database is built around a simple idea: store “meaning” (a vector) alongside the information you need to identify, filter, and show results.

Most records look like this:

doc_18492 or a UUID)For example, a help-center article might store:

kb_123{ "title": "Reset your password", "url": "/help/reset-password", "tags": ["account", "security"] }The vector is what powers semantic similarity. The ID and metadata are what make results usable.

Metadata does two jobs:

Without good metadata, you may retrieve the right meaning but still show the wrong context.

Embedding size depends on the model: 384, 768, 1024, and 1536 dimensions are common. More dimensions can capture nuance, but they also increase:

As a rough intuition: doubling dimensions often pushes up cost and latency unless you compensate with indexing choices or compression.

Real datasets change, so vector databases typically support:

Planning for updates early prevents a “stale knowledge” problem where search returns content that no longer matches what users see.

Once your text, images, or products are converted into embeddings (vectors), search becomes a geometry problem: “Which vectors are nearest to this query vector?” This is called nearest-neighbor search. Instead of matching keywords, the system compares meaning by measuring how close two vectors are.

Picture each piece of content as a point in a huge multi-dimensional space. When a user searches, their query is turned into another point. Similarity search returns the items whose points are closest—your “nearest neighbors.” Those neighbors are likely to share intent, topic, or context, even if they don’t share exact words.

Vector databases typically support a few standard ways to score “closeness”:

Different embedding models are trained with a particular metric in mind, so it’s important to use the one recommended by the model provider.

An exact search checks every vector to find the true nearest neighbors. That can be accurate, but it gets slow and expensive as you scale to millions of items.

Most systems use approximate nearest neighbor (ANN) search. ANN uses smart indexing structures to narrow the search to the most promising candidates. You usually get results that are “close enough” to the true best matches—much faster.

ANN is popular because it lets you tune for your needs:

That tuning is why vector search works well in real apps: you can keep responses snappy while still returning highly relevant results.

Semantic search is easiest to reason about as a simple pipeline: you turn text into meaning, look up similar meaning, then present the most useful matches.

A user types a question (for example: “How do I cancel my plan without losing data?”). The system runs that text through an embeddings model, producing a vector—an array of numbers that represents the query’s meaning rather than its exact words.

That query vector is sent to the vector database, which performs similarity search to find the “closest” vectors among your stored content.

Most systems return top-K matches: the K most similar chunks/documents.

Similarity search is optimized for speed, so the initial top-K can contain near-misses. A reranker is a second model that looks at the query and each candidate result together and re-sorts them by relevance.

Think of it as: vector search gives you a strong shortlist; reranking picks the best order.

Finally, you return the best matches to the user (as search results), or you pass them to an AI assistant (for example, a RAG system) as the “grounding” context.

If you’re building this kind of workflow into an app, platforms like Koder.ai can help you prototype quickly: you describe the semantic search or RAG experience in a chat interface, then iterate on the React front end and Go/PostgreSQL back end while keeping the retrieval pipeline (embedding → vector search → optional rerank → answer) as a first-class part of the product.

If your help center article says “terminate subscription” and the user searches “cancel my plan,” keyword search may miss it because “cancel” and “terminate” don’t match.

Semantic search will typically retrieve it because the embedding captures that both phrases express the same intent. Add reranking, and the top results usually become not just “similar,” but directly actionable for the user’s question.

Pure vector search is great at “meaning,” but users don’t always search by meaning. Sometimes they need an exact match: a person’s full name, a SKU, an invoice ID, or an error code copied from a log. Hybrid search solves this by combining semantic signals (vectors) with lexical signals (traditional keyword search like BM25).

A hybrid query typically runs two retrieval paths in parallel:

The system then merges those candidate results into one ranked list.

Hybrid search shines when your data includes “must-match” strings:

Semantic search alone may return broadly related pages; keyword search alone may miss relevant answers phrased differently. Hybrid covers both failure modes.

Metadata filters restrict retrieval before ranking (or alongside it), improving relevance and speed. Common filters include:

Most systems use a practical blend: run both searches, normalize scores so they’re comparable, then apply weights (e.g., “lean more on keywords for IDs”). Some products also rerank the merged shortlist with a lightweight model or rules, while filters ensure you’re ranking the right subset in the first place.

Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) is a practical pattern for getting more reliable answers from an LLM: first retrieve relevant information, then generate a response that is tied to that retrieved context.

Instead of asking the model to “remember” your company docs, you store those docs (as embeddings) in a vector database, retrieve the most relevant chunks at question time, and pass them into the LLM as supporting context.

LLMs are excellent at writing, but they will confidently fill gaps when they don’t have the needed facts. A vector database makes it easy to fetch the closest-meaning passages from your knowledge base and supply them to the prompt.

That grounding shifts the model from “invent an answer” to “summarize and explain these sources.” It also makes answers easier to audit because you can keep track of which chunks were retrieved and optionally show citations.

RAG quality often depends more on chunking than on the model.

Picture this flow:

User question → Embed question → Vector DB retrieve top-k chunks (+ optional metadata filters) → Build prompt with retrieved chunks → LLM generates answer → Return answer (and sources).

The vector database sits in the middle as the “fast memory” that supplies the most relevant evidence for each request.

Vector databases don’t just make search “smarter”—they enable product experiences where users can describe what they want in natural language and still get relevant results. Below are a few practical use cases that show up again and again.

Support teams often have a knowledge base, old tickets, chat transcripts, and release notes—but keyword search struggles with synonyms, paraphrasing, and vague problem descriptions.

With semantic search, an agent (or a chatbot) can retrieve past tickets that mean the same thing even if the wording is different. That speeds up resolution, reduces duplicated work, and helps new agents ramp faster. Pairing vector search with metadata filters (product line, language, issue type, date range) keeps results focused.

Shoppers rarely know exact product names. They search for intents like “small backpack that fits a laptop and looks professional.” Embeddings capture those preferences—style, function, constraints—so the results feel closer to a human sales assistant.

This approach works for retail catalogs, travel listings, real estate, job boards, and marketplaces. You can also blend semantic relevance with structured constraints such as price, size, availability, or location.

A classic vector-database feature is “find items like this.” If a user views an item, reads an article, or watches a video, you can retrieve other content with similar meaning or attributes—even when categories don’t match perfectly.

This is useful for:

Inside companies, information is scattered across docs, wikis, PDFs, and meeting notes. Semantic search helps employees ask questions naturally (“What’s our reimbursement policy for conferences?”) and find the right source document.

The non-negotiable part is access control. Results must respect permissions—often by filtering on team, document owner, confidentiality level, or an ACL list—so users only retrieve what they’re allowed to see.

If you want to take this further, this same retrieval layer is what powers grounded Q&A systems (covered in the RAG section).

A semantic search system is only as good as the pipeline that feeds it. If documents arrive inconsistently, are chunked poorly, or never get re-embedded after edits, results drift from what users expect.

Most teams follow a repeatable sequence:

The “chunk” step is where many pipelines win or lose. Chunks that are too large dilute meaning; too small lose context. A practical approach is to chunk by natural structure (headings, paragraphs, Q&A pairs) and keep a small overlap for continuity.

Content changes constantly—policies get updated, prices change, articles are rewritten. Treat embeddings as derived data that must be regenerated.

Common tactics:

If you serve multiple languages, you can either use a multilingual embedding model (simpler) or per-language models (sometimes higher quality). If you experiment with models, version your embeddings (e.g., embedding_model=v3) so you can run A/B tests and roll back without breaking search.

Semantic search can feel “good” in a demo and still fail in production. The difference is measurement: you need clear relevance metrics and speed targets, evaluated on queries that look like real user behavior.

Start with a small set of metrics and stick to them over time:

Create an evaluation set from:

Keep the test set versioned so you can compare results across releases.

Offline metrics don’t capture everything. Run A/B tests and collect lightweight signals:

Use this feedback to update relevance judgments and spot failure patterns.

Performance can change when:

Re-run your test suite after any change, monitor metric trends weekly, and set alerts for sudden drops in MRR/nDCG or spikes in p95 latency.

Vector search changes how data is retrieved, but it shouldn’t change who is allowed to see it. If your semantic search or RAG system can “find” the right chunk, it can also accidentally return a chunk the user wasn’t authorized to access—unless you design permissions and privacy into the retrieval step.

The safest rule is simple: a user should only retrieve content they’re allowed to read. Don’t rely on the app to “hide” results after the vector database returns them—because by then the content already left your storage boundary.

Practical approaches include:

Many vector databases support metadata-based filters (e.g., tenant_id, department, project_id, visibility) that run alongside similarity search. Used correctly, this is a clean way to apply permissions during retrieval.

A key detail: ensure the filter is mandatory and server-side, not optional client logic. Also be careful with “role explosion” (too many combinations). If your permission model is complex, consider precomputing “effective access groups” or using a dedicated authorization service to mint a query-time filter token.

Embeddings can encode meaning from the original text. That doesn’t automatically reveal raw PII, but it can still increase risk (e.g., sensitive facts becoming easier to retrieve).

Guidelines that work well:

Treat your vector index as production data:

Done well, these practices make semantic search feel magical to users—without becoming a security surprise later.

Vector databases can feel “plug-and-play,” but most disappointments come from the surrounding choices: how you chunk data, which embedding model you pick, and how reliably you keep everything up to date.

Poor chunking is the #1 cause of irrelevant results. Chunks that are too large dilute meaning; chunks that are too small lose context. If users often say “it found the right document but the wrong passage,” your chunking strategy likely needs work.

The wrong embedding model shows up as consistent semantic mismatch—results are fluent but off-topic. This happens when the model isn’t suited to your domain (legal, medical, support tickets) or your content type (tables, code, multilingual text).

Stale data creates trust issues fast: users search for the latest policy and get last quarter’s version. If your source data changes, your embeddings and metadata must update too (and deletions must actually delete).

Early on, you may have too little content, too few queries, or not enough feedback to tune retrieval. Plan for:

Costs usually come from four places:

If you’re comparing vendors, ask for a simple monthly estimate using your expected document count, average chunk size, and peak QPS. Many surprises happen after indexing and during traffic spikes.

Use this short checklist to choose a vector database that fits your needs:

Choosing well is less about chasing the newest index type and more about reliability: can you keep data fresh, control access, and maintain quality as your content and traffic grow?

Keyword search matches exact tokens. Semantic search matches meaning by comparing embeddings (vectors), so it can return relevant results even when the query uses different phrasing (e.g., “stop payments” → “cancel subscription”).

A vector database stores embeddings (arrays of numbers) plus IDs and metadata, then performs fast nearest-neighbor lookups to find items with the closest meaning to a query. It’s optimized for similarity search at large scale (often millions of vectors).

An embedding is a model-generated numeric “fingerprint” of content. You don’t interpret the numbers directly; you use them to measure similarity.

In practice:

Most records include:

Metadata enables two critical capabilities:

Without metadata, you can retrieve the right meaning but still show the wrong context or leak restricted content.

Common options are:

You should use the metric the embedding model was trained for; the “wrong” metric can noticeably degrade ranking quality.

Exact search compares a query to every vector, which becomes slow and expensive at scale. ANN (approximate nearest neighbor) uses indexes to search a smaller candidate set.

Trade-off you can tune:

Hybrid search combines:

It’s often the best default when your corpus includes “must-match” strings and natural-language queries.

RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation) retrieves relevant chunks from your data store and supplies them as context to an LLM.

A typical flow:

Three high-impact pitfalls:

Mitigations include chunking by structure, versioning embeddings, and enforcing mandatory server-side metadata filters (e.g., , ACL fields).

title, url, tags, language, created_at, tenant_id)The vector powers semantic similarity; metadata makes results usable (filtering, access control, display).

tenant_id