Sep 01, 2025·8 min

How Web Frameworks Abstract Repetitive Work and Ship Faster

Learn how web frameworks reduce repetitive work with proven patterns for routing, data access, auth, security, and tooling—helping teams ship features faster.

Learn how web frameworks reduce repetitive work with proven patterns for routing, data access, auth, security, and tooling—helping teams ship features faster.

Most web apps do the same handful of jobs on every request. A browser (or mobile app) sends a request, the server figures out where it should go, reads input, checks whether the user is allowed, talks to a database, and returns a response. Even when the business idea is unique, the plumbing is familiar.

You’ll see the same patterns in almost every project:

Teams often re-implement these pieces because they feel “small” at first—until inconsistencies pile up and every endpoint behaves slightly differently.

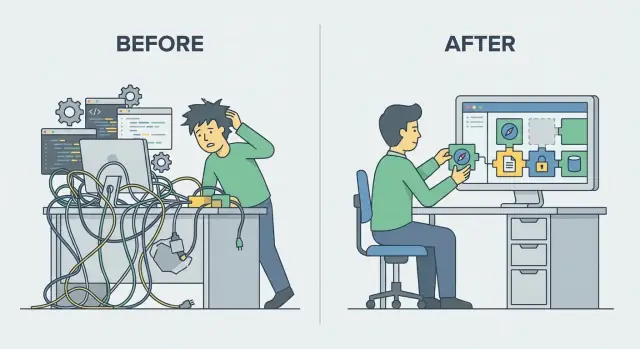

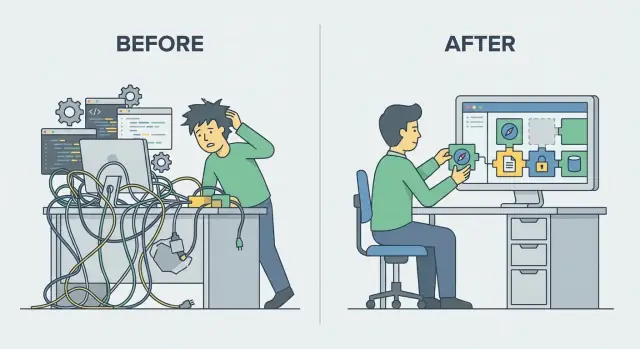

A web framework packages proven solutions to these recurring problems as reusable building blocks (routing, middleware, ORM helpers, templating, testing tools). Instead of re-writing the same code in every controller or endpoint, you configure and compose shared components.

Frameworks usually make you faster, but not for free. You’ll spend time learning conventions, debugging “magic,” and choosing between multiple ways to do the same thing. The goal is not zero code—it’s less duplicated code and fewer avoidable mistakes.

In the rest of this article, we’ll walk through the major areas where frameworks save effort: routing and middleware, validation and serialization, database abstractions, views, auth, security defaults, error handling and observability, dependency injection and configuration, scaffolding, testing, and finally the trade-offs to consider when picking a framework.

Every server-side web app has to answer the same question: “A request came in—what code should handle it?” Without a framework, teams often reinvent routing with ad-hoc URL parsing, long if/else chains, or duplicated wiring across files.

Routing is the part that answers a deceptively simple question: “When someone visits this URL with this method (GET/POST/etc.), which handler should run?”

A router gives you a single, readable “map” of endpoints instead of scattering URL checks across the codebase. Without it, teams end up with logic that’s hard to scan, easy to break, and inconsistent across features.

With routing, you declare intent upfront:

GET /users -> listUsers

GET /users/:id -> getUser

POST /users -> createUser

That structure makes change safer. Need to rename /users to /accounts? You update the routing table (and maybe a few links), rather than hunting through unrelated files.

Routing cuts down on glue code and helps everyone follow the same conventions. It also improves clarity: you can quickly see what your app exposes, what methods are allowed, and which handlers are responsible.

Common routing features you get “for free” include:

:id) so handlers receive structured values instead of manual string slicing/admin or shared rules to many routes/api/v1/...) to evolve APIs without breaking existing clientsIn practice, good routing turns request handling from a repeated puzzle into a predictable checklist.

Middleware is a way to run the same set of steps for many different requests—without copying that logic into every endpoint. Instead of each route manually doing “log the request, check auth, set headers, handle errors…”, the framework lets you define a pipeline that every request passes through.

Think of middleware as checkpoints between the incoming HTTP request and your actual handler (controller/action). Each checkpoint can read or modify the request, short-circuit the response, or add information for the next step.

Common examples include:

A middleware pipeline makes shared behavior consistent by default. If your API should always add security headers, always reject oversized payloads, or always record timing metrics, middleware enforces that uniformly.

It also reduces subtle drift. When the logic lives in one place, you don’t end up with one endpoint that “forgot” to validate a token, or another that logs sensitive fields by accident.

Middleware can be overused. Too many layers make it harder to answer basic questions like “where did this header change?” or “why did this request return early?” Prefer a small number of clearly named middleware steps, and document the order they run in. When something must be route-specific, keep it in the handler rather than forcing everything into the pipeline.

Every web app takes input: HTML forms, query strings, JSON bodies, file uploads. Without a framework, you end up re-checking the same things in every handler—“is this field present?”, “is it an email?”, “is it too long?”, “should whitespace be trimmed?”—and every endpoint invents its own error format.

Frameworks reduce this repetition by making validation and serialization first-class features.

Whether you’re building a signup form or a public JSON API, the rules are familiar:

email, password)Instead of scattering these checks across controllers, frameworks encourage a single schema (or form object) per request shape.

A good validation layer does more than reject bad input. It also normalizes good input consistently:

page=1, limit=20)And when input is invalid, you get predictable error messages and structures—often with field-level details. That means your frontend (or API clients) can rely on a stable response format rather than special-casing each endpoint.

The other half is turning internal objects into safe, public responses. Framework serializers help you:

Together, validation + serialization reduces custom parsing code, prevents subtle bugs, and makes your API feel cohesive even as it grows.

When you talk to a database directly, it’s easy to end up with raw SQL sprinkled across controllers, background jobs, and helper functions. The same patterns repeat: open a connection, build a query string, bind parameters, run it, handle errors, and map rows into objects your app can actually use. Over time, this duplication creates inconsistency (different “styles” of SQL) and mistakes (missing filters, unsafe string concatenation, subtle type bugs).

Most web frameworks ship with (or strongly support) an ORM (Object-Relational Mapper) or a query builder. These tools standardize the repetitive parts of database work:

With models and reusable queries, common CRUD flows stop being hand-written every time. You can define a “User” model once, then reuse it across endpoints, admin screens, and background tasks.

Parameter handling is also safer by default. Instead of manually interpolating values into SQL, ORMs/query builders typically bind parameters for you, reducing the risk of SQL injection and making queries easier to refactor.

Abstractions aren’t free. ORMs can hide expensive queries, and complex reporting queries may be awkward to express cleanly. Many teams use a hybrid approach: ORM for everyday operations, and well-tested raw SQL for the few places where performance tuning or advanced database features matter most.

When an app grows beyond a few pages, the UI starts repeating itself: the same header, navigation, footer, flash messages, and form markup show up everywhere. Web frameworks reduce that copy‑paste by giving you templating systems (or components) that let you define these pieces once and reuse them consistently.

Most frameworks support a base layout that wraps every page: common HTML structure, shared styles/scripts, and a spot where each page injects its unique content. On top of that, you can extract partials/components for recurring patterns—think a login form, a pricing card, or an error banner.

This is more than convenience: changes become safer. Updating a header link or adding an accessibility attribute happens in one file, not twenty.

Frameworks typically offer server-side rendering (SSR) out of the box—rendering HTML on the server from templates plus data. Some also provide component-style abstractions where “widgets” are rendered with props/parameters, improving consistency across pages.

Even if your app uses a front-end framework later, SSR templates often remain useful for emails, admin screens, or simple marketing pages.

Templating engines usually escape variables automatically, turning user-provided text into safe HTML rather than executable markup. That default output encoding helps prevent cross-site scripting (XSS) and also avoids broken pages caused by unescaped characters.

The key benefit: you reuse UI patterns and bake in safer rendering rules, so every new page starts from a consistent, secure baseline.

Authentication answers “who are you?” Authorization answers “what are you allowed to do?” Web frameworks speed this up by giving you a standard way to handle the repetitive plumbing—so you can focus on your app’s actual rules.

Most apps need a way to “remember” a user after login.

Frameworks typically provide high-level configuration for these: how cookies are signed, when they expire, and where session data is stored.

Instead of hand-building every step, frameworks commonly offer reusable login patterns: sign-in, sign-out, “remember me,” password reset, email verification, and protection against common pitfalls like session fixation. They also standardize session storage options (in-memory for development, database/Redis for production) without changing your application code much.

Frameworks also formalize how you protect features:

A key benefit: authorization checks become consistent and easier to audit, because they live in predictable places.

Frameworks don’t decide what “allowed” means. You still must define the rules, review every access path (UI and API), and test edge cases—especially around admin actions and data ownership.

Security work is repetitive: every form needs protection, every response needs safe headers, every cookie needs the right flags. Web frameworks reduce that repetition by shipping sensible defaults and centralized configuration—so you don’t have to reinvent security glue code across dozens of endpoints.

Many frameworks enable (or strongly encourage) safeguards that apply everywhere unless you explicitly opt out:

HttpOnly, Secure, and SameSite, plus consistent session handling.Content-Security-Policy, X-Content-Type-Options, and Referrer-Policy.The key benefit is consistency. Instead of remembering to add the same checks to every route handler, you configure them once (or accept the defaults) and the framework applies them across the app. That reduces copy-paste code and lowers the chance that one forgotten endpoint becomes the weak link.

Framework defaults vary by version and by how you deploy. Treat them as a starting point, not a guarantee.

Read the official security guide for your framework (and any authentication packages), review what’s enabled by default, and keep dependencies updated. Security fixes often arrive as routine patch releases—staying current is one of the simplest ways to avoid repeating old mistakes.

When every route handles failures on its own, error logic spreads quickly: scattered try/catch blocks, inconsistent messages, and forgotten edge cases. Web frameworks reduce that repetition by centralizing how errors are caught, formatted, and recorded.

Most frameworks offer a single error boundary (often a global handler or last middleware) that captures unhandled exceptions and known “fail” conditions.

That means your feature code can focus on the happy path, while the framework handles the boilerplate:

Instead of every endpoint deciding whether to return 400, 404, or 500, you define rules once and reuse them everywhere.

Consistency matters for both people and machines. Framework conventions make it easier to return errors with the right status code and a stable shape, such as:

400 for invalid input (with field-level details)401/403 for authentication/authorization failures404 for missing resources500 for unexpected server errorsFor UI pages, the same central handler can render friendly error screens, while API routes return JSON—without duplicating logic.

Frameworks also standardize visibility by providing hooks around the request lifecycle: request IDs, timing, structured logs, and integrations for tracing/metrics.

Because these hooks run for every request, you don’t have to remember to log start/end in each controller. You get comparable logs across all endpoints, which makes debugging and performance work much faster.

Avoid leaking sensitive details: log full stack traces internally, but return generic public messages.

Keep errors actionable: include a short error code (e.g., INVALID_EMAIL) and, when safe, a clear next step for the user.

Dependency Injection (DI) sounds fancy, but the idea is simple: instead of your code creating the things it needs (a database connection, an email sender, a cache client), it receives them from the framework.

Most web frameworks do this through a service container—a registry that knows how to build shared services and hand them to the right place. That means you stop repeating the same setup code in every controller, handler, or job.

Rather than sprinkling new Database(...) or connect() calls all over your app, you let the framework provide dependencies:

EmailService injected into password reset flows.This reduces glue code and keeps configuration in one place (often a single config module plus environment-specific values).

If a handler receives db or mailer as inputs, tests can pass in a fake or in-memory version. You can verify behavior without sending real emails or hitting a production database.

DI can be overused. If everything depends on everything else, the container becomes a magic box and debugging gets harder. Keep boundaries clear: define small, focused services, avoid circular dependencies, and prefer injecting interfaces (capabilities) over large “god objects.”

Scaffolding is the starter kit many web frameworks provide: a predictable project layout plus generators that create common code for you. Conventions are the rules that make that generated code fit neatly into the rest of the app without manual wiring.

Most frameworks can spin up a new project with a ready-to-run structure (folders for controllers/handlers, models, templates, tests, config). On top of that, generators often create:

The key isn’t that this code is magical—it’s that it follows the same patterns your app will use everywhere else, so you don’t have to invent them each time.

Conventions (naming, folder placement, default wiring) speed onboarding because new teammates can guess where things live and how requests flow. They also reduce style debates that turn into slowdowns: if controllers go in one place and migrations follow a standard pattern, code reviews focus more on behavior than structure.

It shines when you’re building many similar pieces:

Generated code is a starting point, not a final design. Review it like any other code: remove unused endpoints, tighten validation, add authorization checks, and refactor naming to match your domain. Keeping scaffolds unchanged “because the generator did it” can bake in leaky abstractions and extra surface area you didn’t intend to maintain.

Shipping faster only works if you can trust what you ship. Web frameworks help by turning testing into a routine, not a custom project you rebuild for every app.

Most frameworks include a test client that can call your app like a browser would—without running a real server. That means you can send requests, follow redirects, and inspect responses in a few lines.

They also standardize setup tools such as fixtures (known test data), factories (generate realistic records), and easy hooks for mocks (replace external services like email, payments, or third‑party APIs). Instead of hand-crafting data and stubs repeatedly, you reuse a proven recipe across the codebase.

When every test starts from the same predictable state (database cleaned, seed data loaded, dependencies mocked), failures are easier to understand. Developers spend less time debugging test noise and more time fixing real issues. Over time, this reduces the fear of refactors because you have a safety net that actually runs quickly.

Frameworks nudge you toward high-value tests:

Because testing commands, environments, and configuration are standardized, it’s simpler to run the same suite locally and in CI. Predictable one-command test runs make automated checks a default step before merging and deploying.

Frameworks save time by packaging common solutions, but they also introduce costs you should account for early.

A framework is an investment. Expect a learning curve (especially around conventions and “the framework way”), plus ongoing upgrades that may require refactors. Opinionated patterns can be a benefit—less decision fatigue, more consistency—but they can also feel restrictive when your app has unusual requirements.

You also inherit the framework’s ecosystem and release rhythm. If key plugins are unmaintained, or the community is small, you may end up writing the missing pieces yourself.

Start with your team: what do people already know, and what can you hire for later? Next, look at the ecosystem: libraries for routing/middleware, authentication, data access, validation, and testing. Finally, consider long-term maintenance: documentation quality, upgrade guides, versioning policy, and how easy it is to run the app locally and in production.

If you’re comparing options, try building a tiny slice of your product (one page + one form + one database write). The friction you feel there usually predicts the next year.

You don’t need every feature on day one. Pick a framework that lets you adopt components gradually—start with routing, basic templates or API responses, and testing. Add authentication, background jobs, caching, and advanced ORM features only when they solve a real problem.

Frameworks abstract repetition at the code level. A vibe-coding platform like Koder.ai can remove repetition one step earlier: at the project creation level.

If you already know the patterns you want (React on the web, Go services, PostgreSQL, typical auth + CRUD flows), Koder.ai lets you describe the application in chat and generate a working starting point you can iterate on—then export the source code when you’re ready. That’s especially useful for the “tiny slice” evaluation mentioned above: you can quickly prototype a route, a form with validation, and a database write, and see whether the framework conventions and overall structure match how your team likes to work.

Because Koder.ai supports planning mode, snapshots, and rollback, it also pairs well with framework-heavy projects where a refactor can ripple through routing, middleware, and models. You can experiment safely, compare approaches, and keep momentum without turning every structural change into a long manual rewrite.

A good framework reduces repeated work, but the right one is the one your team can sustain.

A web framework packages common, repeatable web-app “plumbing” (routing, middleware, validation, database access, templating, auth, security defaults, testing). You configure and compose these building blocks instead of re-implementing them in every endpoint.

Routing is the centralized map from an HTTP method + URL (like GET /users/:id) to the handler that runs. It reduces repetitive if/else URL checks, makes endpoints easier to scan, and makes changes (like renaming paths) safer and more predictable.

Middleware is a request/response pipeline where shared steps run before/after your handler.

Common uses:

It keeps cross-cutting behavior consistent so individual routes don’t “forget” important checks.

Create a small number of clearly named middleware layers and document the order they run in. Keep route-specific logic in the handler.

Too many layers can make it hard to answer:

Centralized validation lets you define one schema per request shape (required fields, types, formats, ranges) and reuse it.

A good validation layer also normalizes inputs (trimming whitespace, coercing numbers/dates, applying defaults) and returns consistent error shapes your frontend/API clients can rely on.

Serialization turns internal objects into safe, public outputs.

Framework serializers commonly help you:

This cuts glue code and makes your API feel uniform across endpoints.

An ORM/query builder standardizes repetitive DB work:

This speeds up common CRUD work and reduces inconsistencies across the codebase.

Yes. ORMs can hide expensive queries, and complex reporting can be awkward.

A practical approach is hybrid:

The key is to keep the “escape hatch” intentional and reviewed.

Frameworks often provide standard patterns for sessions/cookies and token-based auth, plus reusable flows like login, logout, password reset, and email verification.

They also formalize authorization via roles/permissions, policies, and route guards—so access control lives in predictable places and is easier to audit.

Centralized error handling catches failures in one place and applies consistent rules:

400, 401/403, 404, 500)This reduces scattered boilerplate and improves observability.

try/catch