Nov 25, 2025·8 min

How WebAssembly Changes Programming Languages in the Browser

WebAssembly lets browsers run code from languages beyond JavaScript. Learn what changes, what stays the same, and when WASM is worth it for web apps.

WebAssembly lets browsers run code from languages beyond JavaScript. Learn what changes, what stays the same, and when WASM is worth it for web apps.

WebAssembly (often shortened to WASM) is a compact, low-level bytecode format that modern browsers can run at near-native speed. Instead of shipping source code like JavaScript, a WASM module ships a precompiled set of instructions plus a clear list of what it needs (for example, memory) and what it offers (functions you can call).

Before WASM, the browser effectively had one “universal” runtime for application logic: JavaScript. That was great for accessibility and portability, but it wasn’t ideal for every kind of work. Some tasks—heavy number crunching, real-time audio processing, complex compression, large-scale simulations—can be hard to keep smooth when everything must go through JavaScript’s execution model.

WASM targets a specific problem: a fast, predictable way to run code written in other languages inside the browser, without plugins and without asking users to install anything.

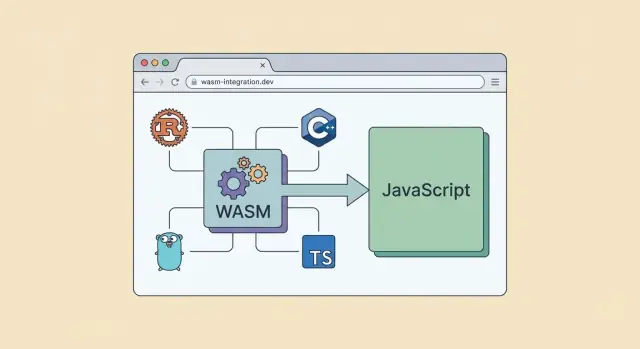

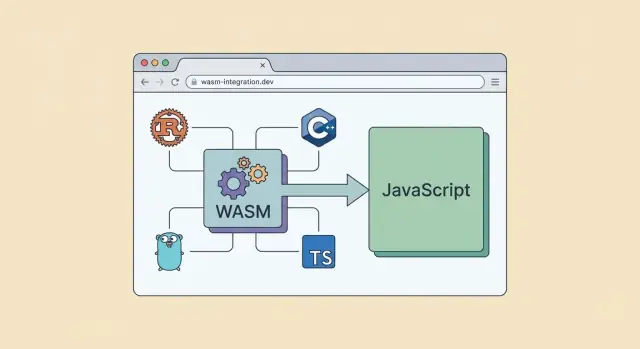

WASM isn’t a new web scripting language, and it doesn’t take over the DOM (the browser’s page UI) by itself. In most apps, JavaScript remains the coordinator: it loads the WASM module, passes data in and out, and handles user interaction. WASM is the “engine room” for the parts that benefit from tight loops and consistent performance.

A useful mental picture:

This article focuses on how WASM changes the role of programming languages in the browser—what it makes possible, where it fits, and what tradeoffs matter for real web apps.

It won’t dive deep into build tooling specifics, advanced memory management, or low-level browser internals. Instead, we’ll keep a practical view: when WASM helps, when it doesn’t, and how to use it without making your frontend harder to maintain.

For most of the web’s history, “running in the browser” effectively meant “running JavaScript.” That wasn’t because JavaScript was always the fastest or most loved language—it was because it was the only language the browser could execute directly, everywhere, without asking users to install anything.

Browsers shipped with a JavaScript engine built in. That made JavaScript the universal option for interactive pages: if you could write JS, your code could reach users on any OS, with a single download, and update instantly when you shipped a new version.

Other languages could be used on the server, but the client side was a different world. The browser runtime had a tight security model (sandboxing), strict compatibility requirements, and a need for fast startup. JavaScript fit that model well enough—and it was standardized early.

If you wanted to use C++, Java, Python, or C# for client-side features, you usually had to translate, embed, or outsource the work. “Client-side” often became shorthand for “rewrite it in JavaScript,” even when the team already had a mature codebase elsewhere.

Before WebAssembly, teams relied on:

These approaches helped, but they hit ceilings for large apps. Transpiled code could be bulky and unpredictable in performance. Plugins were inconsistent across browsers and eventually declined for security and maintenance reasons. Server-side work added latency and cost, and didn’t feel like a true “app in the browser.”

Think of WebAssembly (WASM) as a small, standardized “assembly-like” format that browsers can run efficiently. Your code isn’t written in WASM day-to-day—you produce WASM as a build output.

Most projects follow the same pipeline:

wasm32.wasm module alongside your web appThe important shift is that the browser no longer needs to understand your source language. It only needs to understand WASM.

Browsers don’t execute your Rust or C++ directly. They execute WebAssembly bytecode—a compact, structured binary format designed to be validated quickly and run consistently.

When your app loads a .wasm file, the browser:

In practice, you call WASM functions from JavaScript, and WASM can call back into JavaScript through well-defined interop.

Sandboxed means the WASM module:

This safety model is why browsers are comfortable running WASM from many sources.

Once a browser runs a common bytecode, the question becomes less “Does the browser support my language?” and more “Can my language compile to WASM with good tooling?” That widens the set of practical languages for web apps—without changing what the browser fundamentally executes.

WebAssembly doesn’t replace JavaScript in the browser—it changes the division of labor.

JavaScript still “owns” the page: it reacts to clicks, updates the DOM, talks to browser APIs (like fetch, storage, audio, canvas), and coordinates the app’s lifecycle. If you think in terms of a restaurant, JavaScript is the front-of-house staff—taking orders, managing timing, and presenting the results.

WebAssembly is best treated as a focused compute engine you call from JavaScript. You send it inputs, it does heavy work, and it returns outputs.

Typical tasks include parsing, compression, image/video processing, physics, cryptography, CAD operations, or any algorithm that’s CPU-hungry and benefits from predictable execution. JavaScript remains the glue that decides when to run those operations and how to use the result.

The handoff between JavaScript and WASM is where many real-world performance wins (or losses) happen.

You don’t need to memorize the details to start, but you should expect that “moving data across the boundary” has a cost.

If you call into WASM thousands of times per frame—or copy large chunks of data back and forth—you can erase the benefits of faster computation.

A good rule of thumb: make fewer, bigger calls. Batch work, pass compact data, and let WASM run longer per invocation while JavaScript stays focused on UI, orchestration, and user experience.

WebAssembly is often introduced as “faster than JavaScript,” but the reality is narrower: it can be faster for certain kinds of work, and less impressive for others. The win usually comes when you’re doing a lot of the same computation repeatedly and want a runtime that behaves consistently.

WASM tends to shine on CPU-heavy tasks: image/video processing, audio codecs, physics, data compression, parsing large files, or running parts of a game engine. In those cases, you can keep hot loops inside WASM and avoid the overhead of dynamic typing and frequent allocations.

But WASM isn’t a shortcut for everything. If your app is mostly DOM updates, UI rendering, network requests, or framework logic, you’ll still spend most of your time in JavaScript and the browser’s built-in APIs. WASM can’t directly manipulate the DOM; it has to call into JavaScript, and lots of back-and-forth calls can erase performance gains.

A practical benefit is predictability. WASM executes in a more constrained environment with a simpler performance profile, which can reduce “surprising” slowdowns in tight computational code. That makes it attractive for workloads where consistent frame times or stable processing throughput matter.

WASM binaries can be compact, but tooling and dependencies decide the real download size. A tiny hand-written module can be small; a full Rust/C++ build pulling in standard libraries, allocators, and helper code can be larger than expected. Compression helps, but you still pay for startup, parsing, and instantiation.

Many teams choose WASM to reuse proven native libraries, share code across platforms, or get safer memory and tooling ergonomics (for example, Rust’s guarantees). In those cases, “fast enough and predictable” matters more than chasing the last benchmark point.

WebAssembly doesn’t replace JavaScript, but it opens the door for languages that were previously awkward (or impossible) to run in a browser. The biggest winners tend to be languages that already compile to efficient native code and have ecosystems full of reusable libraries.

Rust is a popular match for browser WASM because it combines fast execution with strong safety guarantees (especially around memory). That makes it attractive for logic you want to keep predictable and stable over time—parsers, data processing, cryptography, and performance-sensitive “core” modules.

Rust’s tooling for WASM is mature, and the community has built patterns for calling into JavaScript for DOM work while keeping heavy computation inside WASM.

C and C++ shine when you already have serious native code you’d like to reuse: codecs, physics engines, image/audio processing, emulators, CAD kernels, and decades-old libraries. Compiling those to WASM can be dramatically cheaper than rewriting them in JavaScript.

The tradeoff is that you inherit the complexity of C/C++ memory management and build pipelines, which can affect debugging and bundle size if you’re not careful.

Go can run in the browser via WASM, but it often carries more runtime overhead than Rust or C/C++. For many apps it’s still viable—especially when you’re prioritizing developer familiarity or sharing code across backend and frontend—but it’s less commonly chosen for tiny, latency-sensitive modules.

Other languages (like Kotlin, C#, Zig) can work too, with varying levels of ecosystem support.

In practice, teams pick a WASM language less for ideology and more for leverage: “What code do we already trust?” and “Which libraries would be expensive to rebuild?” WASM is most valuable when it lets you ship proven components to the browser with minimal translation.

WebAssembly is at its best when you have a chunk of work that’s compute-heavy, reusable, and relatively independent from the DOM. Think of it as a high-performance “engine” you call from JavaScript, while JavaScript still drives the UI.

WASM often pays off when you’re doing the same kind of operation many times per second:

These workloads benefit because WASM runs predictable machine-like code and can keep hot loops efficient.

Some capabilities map naturally to a compiled module that you can treat like a drop-in library:

If you already have a mature C/C++/Rust library, compiling it to WASM can be more realistic than rewriting it in JavaScript.

If most of your time is spent updating the DOM, wiring forms, and calling APIs, WASM typically won’t move the needle. For small CRUD pages, the added build pipeline and JS↔WASM data passing overhead can outweigh benefits.

Use WASM when most answers are “yes”:

If you’re mainly building UI flows, keep it in JavaScript and spend your effort on product and UX.

WebAssembly can make parts of your app faster and more consistent, but it doesn’t remove the browser’s rules. Planning for the constraints upfront helps you avoid rewrites later.

WASM modules don’t directly manipulate the DOM the way JavaScript does. In practice, that means:

If you try to run every tiny UI update through a WASM ↔ JS boundary, you can lose performance to call overhead and data copying.

Most Web Platform features (fetch, WebSocket, localStorage/IndexedDB, canvas, WebGPU, WebAudio, permissions) are exposed as JavaScript APIs. WASM can use them, but usually via bindings or small JS “glue” code.

That introduces two tradeoffs: you’ll maintain interop code, and you’ll think carefully about data formats (strings, arrays, binary buffers) to keep transfers efficient.

Browsers support threads in WASM via Web Workers plus shared memory (SharedArrayBuffer), but it’s not a free default. Using it can require security-related headers (cross-origin isolation) and changes to your deployment setup.

Even with threads available, you’ll design around the browser model: background workers for heavy work, and a responsive main thread for UI.

The tooling story is improving, but debugging can still feel different from JavaScript:

The takeaway: treat WASM as a focused component in your frontend architecture, not a drop-in replacement for the entire app.

WebAssembly works best when it’s a focused component inside a normal web app—not the center of everything. A practical rule: keep the “product surface” (UI, routing, state, accessibility, analytics) in JavaScript/TypeScript, and move only the expensive or specialized parts into WASM.

Treat WASM as a compute engine. JS/TS stays responsible for:

WASM is a strong fit for:

Crossing the JS↔WASM boundary has overhead, so prefer fewer, larger calls. Keep the interface small and boring:

process_v1) so you can evolve safelyWASM can grow quickly when you pull in “one small crate/package” that drags in half the world. To avoid surprises:

A practical split:

This pattern keeps your app feeling like a normal web project—just with a high-performance module where it counts.

If you’re prototyping a WASM-powered feature, speed often comes from getting the architecture right early (clean JS↔WASM boundaries, lazy-loading, and a predictable deployment story). Koder.ai can help here as a vibe-coding platform: you describe the feature in chat, and it can scaffold a React-based frontend plus a Go + PostgreSQL backend, then you iterate on where a WASM module should sit (UI in React, compute in WASM, orchestration in JS/TS) without rebuilding your entire pipeline from scratch.

For teams moving fast, the practical benefit is reducing the “glue work” around the module—wrappers, API endpoints, and rollout mechanics—while still letting you export the source code and host/deploy with custom domains, snapshots, and rollback when you’re ready.

Getting a WebAssembly module into production is less about “can we compile it?” and more about making sure it loads quickly, updates safely, and actually improves the experience for real users.

Most teams ship WASM through the same pipeline as the rest of the frontend: a bundler that understands how to emit a .wasm file and how to reference it at runtime.

A practical approach is to treat the .wasm as a static asset and load it asynchronously so it doesn’t block first paint. Many toolchains generate a small JavaScript “glue” module that handles imports/exports.

// Minimal pattern: fetch + instantiate (works well with caching)

const url = new URL("./my_module.wasm", import.meta.url);

const { instance } = await WebAssembly.instantiateStreaming(fetch(url), {

env: { /* imports */ }

});

If instantiateStreaming isn’t available (or your server sends the wrong MIME type), fall back to fetch(url).then(r => r.arrayBuffer()) and WebAssembly.instantiate.

Because .wasm is a binary blob, you want caching that’s aggressive but safe.

my_module.8c12d3.wasm) so you can set long cache headers.When you iterate frequently, this setup prevents “old JS + new WASM” mismatches and keeps rollouts predictable.

A WASM module can benchmark faster in isolation but still hurt the page if it increases download cost or shifts work onto the main thread.

Track:

Use Real User Monitoring to compare cohorts before/after shipping. If you need help setting up measurement and budgeting, see /pricing, and for related performance articles browse /blog.

Start with one module behind a feature flag, ship it, measure, and only then expand scope. The fastest WASM deployment is the one you can roll back quickly.

WebAssembly can feel “closer to native,” but in the browser it still lives inside the same security model as JavaScript. That’s good news—provided you plan for the details.

WASM runs in a sandbox: it can’t read your user’s files, open arbitrary network sockets, or bypass browser permissions. It only gets capabilities through the JavaScript APIs you choose to expose.

Origin rules still apply. If your app fetches a .wasm file from a CDN or another domain, CORS must allow it, and you should treat that binary as executable code. Use HTTPS, consider Subresource Integrity (SRI) for static assets, and keep a clear update policy (versioned files, cache busting, and rollback plans). A silent “hot swap” of a binary can be harder to debug than a JS deploy.

Many WASM builds pull in C/C++ or Rust libraries that were originally designed for desktop apps. That can expand your trusted code base quickly.

Prefer fewer dependencies, pin versions, and watch for transitive packages that bring cryptography, image parsing, or compression code—areas where vulnerabilities are common. If possible, use reproducible builds and run the same security scanning you’d use for backend code, because your users will execute this code directly.

Not every environment behaves the same (older browsers, embedded webviews, corporate lockdowns). Use feature detection and ship a fallback path: a simpler JS implementation, a reduced feature set, or a server-side alternative.

Treat WASM as an optimization, not the only way your app works. This is especially important for critical flows like checkout or login.

Heavy computation can freeze the main thread—even if it’s written in WASM. Offload work to Web Workers where possible, and keep the UI thread focused on rendering and input.

Load and initialize WASM asynchronously, show progress for large downloads, and design interactions so keyboard and screen-reader users aren’t blocked by long-running tasks. A fast algorithm isn’t helpful if the page feels unresponsive.

WebAssembly changes what “browser programming language” means. Before, “runs in the browser” mostly implied “written in JavaScript.” Now it can mean: written in many languages, compiled to a portable binary, and executed safely inside the browser—with JavaScript still coordinating the experience.

After WASM, the browser is less like a JavaScript-only engine and more like a runtime that can host two layers:

That shift doesn’t replace JavaScript; it widens your options for parts of an app.

JavaScript (and TypeScript) stays central because the web platform is designed around it:

Think of WASM as a specialized engine you attach to your app, not a new way to build everything.

Expect incremental improvements rather than a sudden “rewrite the web” moment. Tooling, debugging, and interop are getting smoother, and more libraries are offering WASM builds. At the same time, the browser will keep favoring secure boundaries, explicit permissions, and predictable performance—so not every native pattern will translate cleanly.

Before adopting WASM, ask:

If you can’t answer these confidently, stick with JavaScript first—and add WASM when the payoff is obvious.

WebAssembly (WASM) is a compact, low-level bytecode format that browsers can validate and run efficiently.

You typically write code in Rust/C/C++/Go, compile it to a .wasm binary, then load and call it from JavaScript.

Browsers added WASM to enable fast, predictable execution of code written in languages other than JavaScript—without plugins.

It targets workloads like tight loops and heavy computation where performance and consistency matter.

No. In most real apps, JavaScript remains the coordinator:

WASM is best used as a compute-focused component, not a full UI replacement.

WASM doesn’t directly manipulate the DOM. If you need to update UI, you typically:

Trying to route frequent UI changes through WASM usually adds overhead.

Good candidates are CPU-heavy, repeatable tasks with clean inputs/outputs:

If your app is mostly forms, network calls, and DOM updates, WASM typically won’t help much.

You pay for:

A practical rule: make fewer, bigger calls and keep large loops inside WASM to avoid boundary costs.

Data transfer is where many projects win or lose performance:

TypedArray views over WASM memory buffersBatch work and use compact binary formats when possible.

Common choices:

In practice, teams often choose based on existing libraries and codebases they already trust.

Yes—WASM runs in a sandbox:

You should still treat .wasm as executable code: use HTTPS, manage updates carefully, and be cautious with third-party native dependencies.

A practical deployment checklist:

.wasm as a static asset and load it asynchronouslyinstantiateStreamingIf you need related measurement guidance, see /blog.