Jun 09, 2025·8 min

How to Improve an App Over Time Without Rewriting Everything

Learn practical ways to improve an app over time—refactoring, testing, feature flags, and gradual replacement patterns—without a risky full rewrite.

Learn practical ways to improve an app over time—refactoring, testing, feature flags, and gradual replacement patterns—without a risky full rewrite.

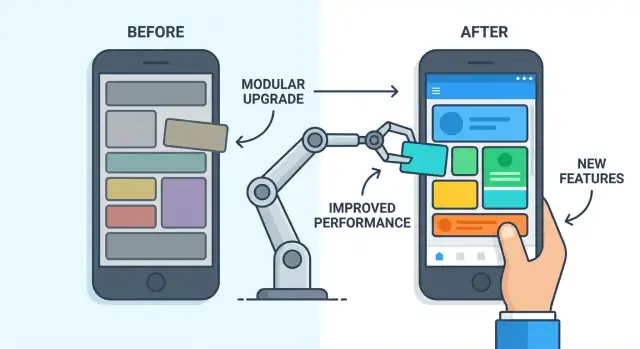

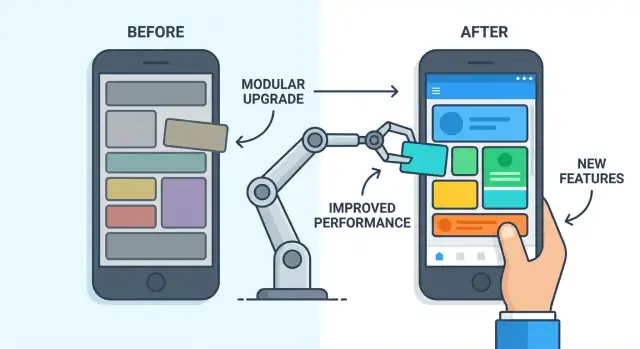

Improving an app without rewriting it means making small, continuous changes that add up over time—while the existing product keeps running. Instead of a “stop everything and rebuild” project, you treat the app like a living system: you fix pain points, modernize parts that slow you down, and steadily raise quality with each release.

Incremental improvement usually looks like:

The key is that users (and the business) still get value along the way. You ship improvements in slices, not in one giant delivery.

A full rewrite can feel appealing—new tech, fewer constraints—but it’s risky because it tends to:

Often, the current app contains years of product learning. A rewrite can accidentally throw that away.

This approach isn’t overnight magic. Progress is real, but it shows up in measurable ways: fewer incidents, faster release cycles, improved performance, or reduced time to implement changes.

Incremental improvement requires alignment across product, design, engineering, and stakeholders. Product helps prioritize what matters most, design ensures changes don’t confuse users, engineering keeps changes safe and sustainable, and stakeholders support steady investment rather than betting everything on a single deadline.

Before you refactor code or buy new tools, get clear on what’s actually hurting. Teams often treat symptoms (like “the code is messy”) when the real issue is a bottleneck in review, unclear requirements, or missing test coverage. A quick diagnosis can save months of “improvements” that don’t move the needle.

Most legacy apps don’t fail in one dramatic way—they fail through friction. Typical complaints include:

Pay attention to patterns, not one-off bad weeks. These are strong indicators you’re dealing with systemic problems:

Try grouping findings into three buckets:

This keeps you from “fixing” the code when the real problem is that requirements arrive late or change mid-sprint.

Pick a handful of metrics you can track consistently before any changes:

These numbers become your scoreboard. If refactoring doesn’t reduce hotfixes or cycle time, it’s not helping—yet.

Technical debt is the “future cost” you take on when you choose the quick solution now. Like skipping routine car maintenance: you save time today, but you’ll likely pay more later—with interest—through slower changes, more bugs, and stressful releases.

Most teams don’t create technical debt on purpose. It accumulates when:

Over time, the app still works—but making any change feels risky, because you’re never sure what else you’ll break.

Not all debt deserves immediate attention. Focus on the items that:

A simple rule: if a part of the code is touched often and fails often, it’s a good candidate for cleanup.

You don’t need a separate system or long documents. Use your existing backlog and add a tag like tech-debt (optionally tech-debt:performance, tech-debt:reliability).

When you find debt during feature work, create a small, concrete backlog item (what to change, why it matters, how you’ll know it’s better). Then schedule it alongside product work—so debt stays visible and doesn’t quietly pile up.

If you try to “improve the app” without a plan, every request sounds equally urgent and the work turns into scattered fixes. A simple, written plan makes improvements easier to schedule, explain, and defend when priorities shift.

Start by choosing 2–4 goals that matter to the business and users. Keep them concrete and easy to discuss:

Avoid goals like “modernize” or “clean up code” on their own. Those can be valid activities, but they should support a clear outcome.

Choose a near-term window—often 4–12 weeks—and define what “better” means using a handful of measures. For example:

If you can’t measure it precisely, use a proxy (support ticket volume, time-to-resolve incidents, user drop-off rate).

Improvements compete with features. Decide upfront how much capacity is reserved for each (for example, 70% features / 30% improvements, or alternating sprints). Put it in the plan so improvement work doesn’t vanish the moment a deadline appears.

Share what you will do, what you won’t do yet, and why. Agree on the trade-offs: a slightly later feature release might buy fewer incidents, faster support, and more predictable delivery. When everyone signs onto the plan, it’s easier to stick with incremental improvement instead of reacting to the loudest request.

Refactoring is reorganizing code without changing what the app does. Users shouldn’t notice anything different—same screens, same results—while the inside becomes easier to understand and safer to change.

Begin with changes that are unlikely to affect behavior:

These steps reduce confusion and make future improvements cheaper, even if they don’t add new features.

A practical habit is the boy scout rule: leave the code a little better than you found it. If you’re already touching a part of the app to fix a bug or add a feature, take a few extra minutes to tidy that same area—rename one function, extract one helper, delete dead code.

Small refactors are easier to review, easier to undo, and less likely to introduce subtle bugs than big “cleanup projects.”

Refactoring can drift without clear finish lines. Treat it like real work with clear completion criteria:

If you can’t explain the refactor in one or two sentences, it’s probably too large—split it into smaller steps.

Improving a live app is much easier when you can tell—quickly and confidently—whether a change broke something. Automated tests provide that confidence. They don’t eliminate bugs, but they sharply reduce the risk of “small” refactors turning into expensive incidents.

Not every screen needs perfect coverage on day one. Prioritize tests around the flows that would hurt the business or users the most if they fail:

These tests act like guardrails. When you later improve performance, reorganize code, or replace parts of the system, you’ll know if the essentials still work.

A healthy test suite usually blends three types:

When you’re touching legacy code that “works but nobody knows why,” write characterization tests first. These tests don’t judge whether behavior is ideal—they simply lock in what the app does today. Then you refactor with less fear, because any accidental behavior change shows up immediately.

Tests only help if they stay reliable:

Once this safety net exists, you can improve the app in smaller steps—and ship more often—with much less stress.

When a small change triggers unexpected breakage in five other places, the problem is usually tight coupling: parts of the app depend on each other in hidden, fragile ways. Modularizing is the practical fix. It means separating the app into parts where most changes stay local, and where connections between parts are explicit and limited.

Start with areas that already feel like “products within the product.” Common boundaries include billing, user profiles, notifications, and analytics. A good boundary typically has:

If the team argues about where something belongs, that’s a sign the boundary needs to be defined more clearly.

A module isn’t “separate” just because it’s in a new folder. The separation is created by interfaces and data contracts.

For example, instead of many parts of the app reading billing tables directly, create a small billing API (even if it’s just an internal service/class at first). Define what can be asked and what will be returned. This lets you change billing internals without rewriting the rest of the app.

Key idea: make dependencies one-way and intentional. Prefer passing stable IDs and simple objects over sharing internal database structures.

You don’t need to redesign everything up front. Pick one module, wrap its current behavior behind an interface, and move code behind that boundary step by step. Each extraction should be small enough to ship, so you can confirm nothing else broke—and so improvements don’t ripple through the whole codebase.

A full rewrite forces you to bet everything on one big launch. The strangler approach flips that: you build new capabilities around the existing app, route only the relevant requests to the new parts, and gradually “shrink” the old system until it can be removed.

Think of your current app as the “old core.” You introduce a new edge (a new service, module, or UI slice) that can handle a small piece of functionality end-to-end. Then you add routing rules so some traffic uses the new path while everything else continues to use the old one.

Concrete examples of “small pieces” worth replacing first:

/users/{id}/profile in a new service, but leave other endpoints in the legacy API.Parallel runs reduce risk. Route requests using rules like: “10% of users go to the new endpoint,” or “only internal staff use the new screen.” Keep fallbacks: if the new path errors or times out, you can serve the legacy response instead, while capturing logs to fix the issue.

Retirement should be a planned milestone, not an afterthought:

Done well, the strangler approach delivers visible improvements continuously—without the “all-or-nothing” risk of a rewrite.

Feature flags are simple switches in your app that let you turn a new change on or off without redeploying. Instead of “ship it to everyone and hope,” you can ship the code behind a disabled switch, then enable it carefully when you’re ready.

With a flag, the new behavior can be limited to a small audience first. If anything goes wrong, you can flip the switch off and get an instant rollback—often faster than reverting a release.

Common rollout patterns include:

Feature flags can turn into a messy “control panel” if you don’t manage them. Treat each flag like a mini project:

checkout_new_tax_calc).Flags are great for risky changes, but too many can make the app harder to understand and test. Keep critical paths (login, payments) as simple as possible, and remove old flags promptly so you don’t end up maintaining multiple “versions” of the same feature forever.

If improving the app feels risky, it’s often because shipping changes is slow, manual, and inconsistent. CI/CD (Continuous Integration / Continuous Delivery) makes delivery routine: every change is handled the same way, with checks that catch issues early.

A simple pipeline doesn’t need to be fancy to be useful:

The key is consistency. When the pipeline is the default path, you stop relying on “tribal knowledge” to ship safely.

Large releases turn debugging into detective work: too many changes land at once, so it’s unclear what caused a bug or slowdown. Smaller releases make cause-and-effect clearer.

They also reduce coordination overhead. Instead of scheduling a “big release day,” teams can ship improvements as they’re ready, which is especially valuable when you’re doing incremental improvement and refactoring.

Automate the easy wins:

These checks should be fast and predictable. If they’re slow or flaky, people will ignore them.

Document a short checklist in your repo (for example, /docs/releasing): what must be green, who approves, and how you verify success after deploy.

Include a rollback plan that answers: How do we revert quickly? (previous version, config switch, or database-safe rollback steps). When everyone knows the escape hatch, shipping improvements feels safer—and happens more often.

Tooling note: If your team is experimenting with new UI slices or services as part of incremental modernization, a platform like Koder.ai can help you prototype and iterate quickly via chat, then export the source code and integrate it into your existing pipeline. Features like snapshots/rollback and planning mode are especially useful when you’re shipping small, frequent changes.

If you can’t see how your app behaves after release, every “improvement” is partly guesswork. Production monitoring gives you evidence: what’s slow, what’s breaking, who is affected, and whether a change helped.

Think of observability as three complementary views:

A practical start is to standardize a few fields everywhere (timestamp, environment, request ID, release version) and make sure errors include a clear message and stack trace.

Prioritize signals customers feel:

An alert should answer: who owns it, what is broken, and what to do next. Avoid noisy alerts based on a single spike; prefer thresholds over a window (e.g., “error rate >2% for 10 minutes”) and include links to the relevant dashboard or runbook (/blog/runbooks).

Once you can connect issues to releases and user impact, you can prioritize refactoring and fixes by measurable outcomes—fewer crashes, faster checkout, lower payment failures—not by gut feel.

Improving a legacy app isn’t a one-time project—it’s a habit. The easiest way to lose momentum is to treat modernization as “extra work” that no one owns, measured by nothing, and postponed by every urgent request.

Make it clear who owns what. Ownership can be by module (billing, search), by cross-cutting areas (performance, security), or by services if you’ve split the system.

Ownership doesn’t mean “only you can touch it.” It means one person (or a small group) is responsible for:

Standards work best when they’re small, visible, and enforced in the same place every time (code review and CI). Keep them practical:

Document the minimum in a short “Engineering Playbook” page so new teammates can follow it.

If improvement work is always “when there’s time,” it will never happen. Reserve a small, recurring budget—monthly cleanup days or quarterly goals tied to one or two measurable outcomes (fewer incidents, faster deploys, lower error rate).

The usual failure modes are predictable: trying to fix everything at once, making changes without metrics, and never retiring old code paths. Plan small, verify impact, and delete what you replace—otherwise complexity only grows.

Start by deciding what “better” means and how you’ll measure it (e.g., fewer hotfixes, faster cycle time, lower error rate). Then reserve explicit capacity (like 20–30%) for improvement work and ship it in small slices alongside features.

Because rewrites often take longer than planned, recreate old bugs, and miss “invisible features” (edge cases, integrations, admin workflows). Incremental improvements keep delivering value while reducing risk and preserving product learnings.

Look for recurring patterns: frequent hotfixes, long onboarding, “untouchable” modules, slow releases, and high support load. Then sort findings into process, code/architecture, and product/requirements so you don’t fix code when the real problem is approvals or unclear specs.

Track a small baseline you can review weekly:

Use these as your scoreboard; if changes don’t move the numbers, adjust the plan.

Treat tech debt as a backlog item with a clear outcome. Prioritize debt that:

Tag items lightly (e.g., tech-debt:reliability) and schedule them alongside product work so they stay visible.

Make refactors small and behavior-preserving:

If you can’t summarize the refactor in 1–2 sentences, split it.

Start with tests that protect revenue and core usage (login, checkout, imports/jobs). Add characterization tests before touching risky legacy code to lock in current behavior, then refactor with confidence. Keep UI tests stable with data-test selectors and limit end-to-end tests to critical journeys.

Identify “product-like” areas (billing, profiles, notifications) and create explicit interfaces so dependencies become intentional and one-way. Avoid letting multiple parts of the app read/write the same internals directly; instead, route access through a small API/service layer that you can change independently.

Use gradual replacement (often called the strangler approach): build a new slice (one screen, one endpoint, one background job), route a small percentage of traffic to it, and keep a fallback to the legacy path. Increase traffic gradually (10% → 50% → 100%), then freeze and delete the old path deliberately.

Use feature flags and staged rollouts:

Keep flags clean with clear naming, ownership, and an expiration date so you don’t maintain multiple versions forever.