Dec 02, 2025·8 min

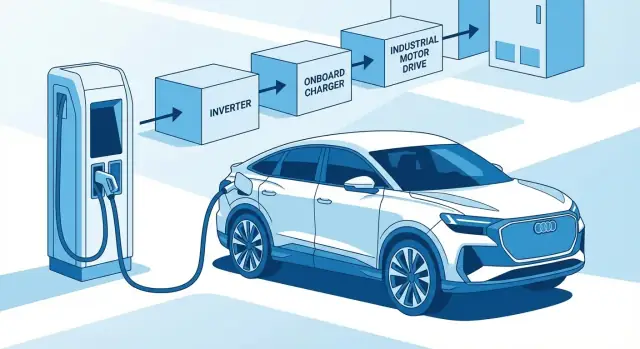

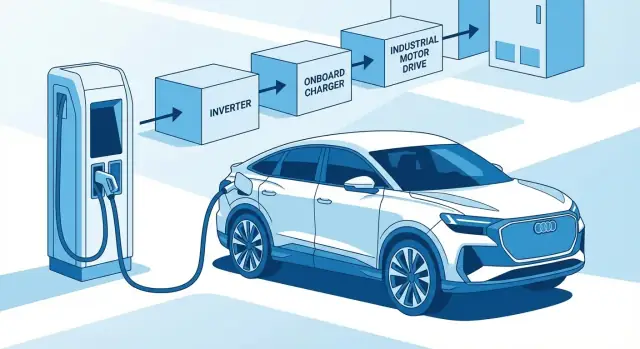

Infineon and EVs: Power Semiconductors for Charging & More

Learn how Infineon’s power electronics and automotive semiconductors enable EV drivetrains, fast charging, and efficient industrial motors—plus key terms to know.

Learn how Infineon’s power electronics and automotive semiconductors enable EV drivetrains, fast charging, and efficient industrial motors—plus key terms to know.

If you care about EV range, charging speed, and long-term reliability, you’re ultimately talking about how efficiently electrical energy is converted and controlled. That job is done by semiconductors—especially power semiconductors that act like ultra-fast, high-current switches.

Infineon matters because it’s one of the major suppliers of these “gatekeepers” of energy flow. When switching losses are lower and heat is easier to manage, more of the battery’s energy reaches the wheels, less is wasted during charging, and components can be smaller—or last longer.

This is a practical, non-technical overview of the key building blocks inside:

Along the way, we’ll connect the dots: higher efficiency can translate into more range, shorter charge sessions, and less thermal stress—a major driver of reliability.

It helps to separate two categories that often get lumped together:

Both matter, but power electronics are the reason an EV can move, a fast charger can deliver hundreds of kilowatts, and an industrial motor system can save significant energy over its lifetime.

Power electronics is “traffic control” for electricity: it decides how much energy moves, in what direction, and how quickly it can change. Before diving into EV inverters or chargers, a few simple ideas make everything else easier to follow.

When an EV accelerates or a fast charger ramps up, power electronics manages that power delivery while trying to waste as little as possible as heat.

A power switch is a semiconductor device that can turn energy flow on and off extremely fast—thousands to millions of times per second. By switching rapidly (instead of “resisting” the flow like an old-style control knob), systems can control motor speed, charging current, and voltage levels with far higher efficiency.

(Infineon and its peers ship these as discrete components and as high-power modules designed for automotive and industrial environments.)

Two primary loss mechanisms are:

Both become heat. Less loss usually means smaller heatsinks, lighter cooling systems, and more compact hardware—big advantages in EVs and chargers where space, weight, and reliability margins are tight.

An EV battery stores energy as DC (direct current), but most traction motors run on AC (alternating current). The traction inverter is the translator: it takes high-voltage DC from the pack and creates a precisely controlled three‑phase AC waveform that spins the motor.

A simple mental model looks like this:

Battery (DC) → Inverter (DC-to-AC) → Motor (AC torque)

The inverter isn’t just a “power box”—it strongly influences driving behavior:

Many EV inverters are built from multiple layers:

Design choices are a constant negotiation between cost, efficiency, and compactness. Higher efficiency can reduce cooling needs and enable smaller housings, but may require more advanced devices or packaging. Compact designs, in turn, demand excellent thermal performance so the inverter stays reliable under towing, repeated acceleration, or hot weather.

When people talk about EV charging, they picture the charge port and the station. Inside the car, two less-visible systems do a lot of the work: the onboard charger (OBC) and the high-voltage to low-voltage DC/DC converter.

The OBC is the EV’s “AC charging computer.” Most home and workplace charging delivers AC power from the grid, but the battery stores DC power. The OBC converts AC-to-DC and applies the charging profile the battery requires.

A simple way to remember the split:

Even with a large high-voltage battery, EVs still rely on a 12 V (or 48 V) system for lights, infotainment, ECUs, pumps, and safety systems. The DC/DC converter steps the traction battery voltage down efficiently and keeps the auxiliary battery charged.

Modern OBCs and DC/DC converters use fast switching semiconductors to reduce the size of magnetic components (inductors/transformers) and filtering. Higher switching frequency can enable:

This is where device choices—silicon MOSFETs/IGBTs vs. SiC MOSFETs—directly affect how compact and efficient a charger can be.

An OBC isn’t only about “turning AC into DC.” It must also handle:

Higher charging power increases current and switching stress. Semiconductor selection influences efficiency, heat generation, and cooling requirements, which can limit sustained charging power. Lower losses can mean faster charging within the same thermal budget—or simpler, quieter cooling hardware.

DC fast charging looks simple from the outside—plug in, watch the percentage climb—but inside the cabinet it’s a staged power-conversion system. The speed, efficiency, and uptime are largely determined by the power semiconductors and how they’re packaged, cooled, and protected.

Most high-power chargers have two main blocks:

In both stages, switching devices (IGBTs or SiC MOSFETs), gate drivers, and control ICs determine how compact the charger can be and how cleanly it interacts with the grid.

A 1–2% efficiency difference sounds small, but at 150–350 kW it becomes meaningful. Higher efficiency means:

Fast chargers face surges, frequent thermal cycling, dust and humidity, and sometimes salt-air exposure. Semiconductors enable fast protective functions such as fault shutdown, current/voltage monitoring, and isolation boundaries between high-voltage power and low-voltage controls.

Interoperability and safety also depend on dependable sensing and fault handling: insulation monitoring, ground-fault detection, and safe discharge paths help ensure the charger and vehicle can stop power flow quickly when something goes wrong.

Integrated power modules (instead of many discrete parts) can simplify layout, reduce stray inductance, and make cooling more predictable. For operators, modular power stages can also make servicing easier: swap a module, validate, and return the charger to operation faster.

Choosing between silicon (Si) and silicon carbide (SiC) power devices is one of the biggest levers EV and charger designers have. It affects efficiency, thermal behavior, component size, and sometimes even the shape of a vehicle’s charging curve.

SiC is a “wide-bandgap” material. In plain terms, it tolerates higher electric fields and higher operating temperatures before it starts leaking current or breaking down. For power electronics, that translates into devices that can block high voltage with lower losses and switch faster—useful in traction inverters and DC fast charging.

Silicon (often as IGBTs or silicon MOSFETs) is mature, widely available, and cost-effective. It performs well, especially when switching speeds don’t need to be extreme.

SiC MOSFETs typically deliver:

Those gains can help extend driving range or allow sustained fast charging with less thermal throttling.

IGBT modules remain popular in many 400 V traction inverters, industrial drives, and cost-sensitive platforms. They’re proven, robust, and competitive when the design prioritizes price, established supply chains, and switching frequencies that don’t push silicon too hard.

Faster switching (a SiC strength) can unlock smaller magnetics—inductors and transformers in onboard chargers, DC/DC converters, and some charger stages. Smaller magnetics reduce weight and volume and can improve transient response.

Efficiency and size benefits depend on the whole design: gate driving, layout inductance, EMI filtering, cooling, control strategy, and operating margins. A well-optimized silicon design can outperform a poorly implemented SiC one—so material choice should follow system goals, not headlines.

Power semiconductors don’t just need the “right chip.” They need the right package—the physical form that carries high current, connects to the rest of the system, and moves heat away fast enough to stay within safe limits.

When an EV inverter or charger switches hundreds of amps, even small electrical losses become significant heat. If that heat can’t escape, the device runs hotter, efficiency drops, and parts age faster.

Packaging solves two practical problems at once:

This is why EV-grade power designs pay close attention to copper thickness, bonding methods, baseplates, and thermal interface materials.

A discrete device is a single power switch mounted on a circuit board—useful for smaller power levels and flexible layouts.

A power module groups multiple switches (and sometimes sensors) into one block designed for high current and controlled heat flow. Think of it as a pre-engineered “power building block” rather than assembling everything from individual bricks.

EV and industrial environments punish hardware: vibration, humidity, and repeated thermal cycling (hot–cold–hot) can fatigue bonds and solder over time. Strong packaging choices and conservative temperature margins improve lifetime—helping designers push power density without sacrificing durability.

An EV battery pack is only as good as the system supervising it. The Battery Management System (BMS) measures what’s happening inside the pack, keeps cells aligned through balancing, and steps in fast when something looks unsafe.

At a high level, a BMS has three jobs:

BMS decisions depend on accurate sensing:

Small accuracy errors compound into bad range estimates, uneven aging, or late fault detection—especially under high load or fast charging.

High-voltage packs must keep control electronics electrically separated from the power domain. Isolation (isolated amplifiers, isolated communication, insulation monitoring) protects passengers and technicians, improves noise immunity, and enables reliable measurement even in the presence of hundreds of volts.

Functional safety is largely about designing systems that detect faults, enter a safe state, and avoid single points of failure. Semiconductor building blocks support this with self-tests, redundant measurement paths, watchdogs, and defined failure reporting.

Modern battery electronics can flag abnormal sensor readings, detect open wires, monitor isolation resistance, and timestamp events for post-fault analysis—turning “something’s wrong” into actionable protection.

Motor drives are one of the biggest “quiet” users of electricity in industry. Anytime a factory needs motion—spinning, pumping, moving, compressing—power electronics sits between the grid and the motor to shape energy into controlled torque and speed.

A variable-speed drive (VSD) typically rectifies incoming AC power, smooths it on a DC link, then uses an inverter stage (often an IGBT module or SiC MOSFETs, depending on voltage and efficiency goals) to create a controlled AC output for the motor.

You’ll find these drives in pumps, fans, compressors, and conveyors—systems that often run for long hours and dominate a site’s energy bill.

Constant-speed operation wastes energy when the process doesn’t need full output. A pump or fan throttled by a valve or damper still consumes near-full power, but a VSD can reduce motor speed instead. For many centrifugal loads (fans/pumps), a small speed reduction can produce a much larger power reduction, translating into real efficiency gains.

Modern industrial power devices improve drive performance in practical ways:

Higher-quality motor control often means quieter operation, smoother starts/stops, less mechanical wear, and better process stability—sometimes as valuable as the energy savings themselves.

EVs don’t exist in isolation. Every new charger plugs into a grid that also has to absorb more solar, wind, and battery storage. The same power conversion concepts used inside the car show up in solar inverters, wind converters, stationary storage, and the equipment that feeds charging sites.

Renewables are variable by nature: clouds move, wind gusts change, and batteries switch between charging and discharging. Power electronics acts like a translator between these sources and the grid, shaping voltage and current so energy can be delivered smoothly and safely.

Bidirectional systems can move energy both ways: grid → vehicle (charging) and vehicle → home/grid (supplying). Conceptually, it’s the same hardware doing the switching, but with controls and safety features designed for exporting power. Even if you never use vehicle-to-home or vehicle-to-grid, the bidirectional requirement influences how next-generation inverters and chargers are designed.

Conversion can distort the AC waveform. Those distortions are called harmonics, and they can heat equipment or cause interference. Power factor measures how cleanly a device draws power; closer to 1 is better. Modern converters use active control to reduce harmonics and improve power factor, helping the grid handle more chargers and renewables.

Grid equipment is expected to run for years, often outdoors, with predictable maintenance. That pushes designs toward durable packaging, strong protection features, and modular parts that can be serviced quickly.

As charging grows, upstream upgrades—transformers, switchgear, and site-level power conversion—often become part of the project scope, not just the chargers themselves.

Selecting power semiconductors (whether an Infineon module, a discrete MOSFET, or a full gate-driver + sensing ecosystem) is less about chasing peak specs and more about matching real operating conditions.

Define the non-negotiables early:

Before picking Si vs SiC, confirm what your product can physically support:

Higher efficiency can reduce heatsink size, pump power, warranty risk, and downtime. Factor in maintenance, energy losses over life, and uptime requirements—especially for DC fast charging and industrial drives.

For automotive and infrastructure, supply strategy is part of engineering:

Budget time for EMC and safety work: isolation coordination, functional safety expectations, fault handling, and documentation for audits.

Define validation artifacts up front: efficiency maps, thermal cycling results, EMI reports, and field diagnostics (temperature/current trends, fault codes). A clear plan reduces late redesigns and speeds certification.

Even hardware-heavy programs end up needing software: charger fleet monitoring, inverter efficiency-map visualization, test-data dashboards, service tools, internal BOM/configuration portals, or simple apps to track thermal derating behavior across variants.

Platforms like Koder.ai can help teams build these supporting web, backend, and mobile tools quickly via a chat-driven workflow (with planning mode, snapshots/rollback, and source-code export). That can be a practical way to shorten the “last mile” between lab results and deployable internal apps—especially when multiple engineering groups need the same data in different formats.

Power semiconductors are the muscle and reflexes of modern electrification: they switch energy efficiently, measure it accurately, and keep systems safe under real-world heat, vibration, and grid conditions.

Does SiC always mean faster charging?

Not automatically. SiC can reduce losses and enable higher frequency/smaller magnetics, but charging speed is usually capped by battery chemistry/temperature, charger rating, and grid constraints.

Is an IGBT “outdated” for EVs?

No. Many platforms still use IGBT modules effectively, especially where cost, proven reliability, and specific efficiency targets make sense.

What matters most for reliability?

Thermal margins, package/module selection, good gate-drive tuning, isolation integrity, and protection features (overcurrent/overvoltage/overtemperature).

If you’re comparing solutions, start here:

Voltage & power level → sets device class (e.g., 400V vs 800V, kW range).

Efficiency target & cooling budget → pushes toward SiC and/or better packaging/thermal path.

EMI constraints → influences switching speed, gate driver choice, filters, and layout.

Cost & supply strategy → module vs discretes, qualification level, second-sourcing.

Expect continued gains from higher efficiency in real drive cycles, tighter thermal limits (smaller cooling systems), and more integration (smart power modules, advanced gate drivers, and improved isolation) that simplify design while raising performance.

Infineon is a major supplier of power semiconductors—the high-voltage, high-current switches that control how efficiently energy moves in EVs, chargers, and industrial equipment. Lower losses mean:

Power electronics handles energy conversion and control (voltage, current, heat, efficiency) in things like inverters, onboard chargers, DC/DC converters, and motor drives. Signal/logic electronics handles information (control, communication, sensing, computing). EV performance and charging speed are heavily constrained by the power side because that’s where most losses and heat are created.

A traction inverter converts battery DC into three‑phase AC for the motor. It affects:

In practice: better switching + better thermal design usually improves sustained performance and efficiency.

A power semiconductor “switch” turns current on/off extremely fast (thousands to millions of times per second). Instead of wasting energy like a resistor-based control, rapid switching lets the system shape voltage and current precisely with higher efficiency—critical for motor control, charging control, and DC/DC conversion.

Common building blocks include:

Many products combine these into for easier high-power design and cooling.

Two main buckets:

Both become heat, which forces bigger heatsinks, liquid cooling, or power limiting. Improving efficiency often translates into smaller hardware or higher sustained output within the same thermal limits.

In AC charging, the car’s onboard charger (OBC) converts grid AC to DC for the battery. In DC fast charging, the station does the AC-to-DC conversion and sends DC directly to the vehicle.

Practical implication: OBC design affects home/work charging speed and efficiency, while fast-charger power stages affect site efficiency, heat, and uptime.

Not automatically. SiC can reduce losses and enable higher switching frequencies (which can shrink magnetics and improve efficiency), but charging speed is usually limited by the whole chain:

SiC often helps sustain high power with less heat, but it doesn’t override battery limits.

No. IGBTs are still widely used—especially in 400 V traction inverters, many industrial drives, and cost-sensitive platforms—because they’re proven, robust, and can be very competitive at appropriate switching frequencies. The “best” choice depends on voltage class, efficiency targets, cooling budget, and cost/supply constraints.

A practical shortlist is:

Reliability is usually won by system-level design discipline, not a single component choice.