Dec 10, 2025·8 min

Integrations directory design that scales from 3 to 30 apps

Design an integrations directory that scales from 3 to 30 integrations with a simple data model, clear statuses, permissions, and setup progress UI.

What an integrations screen needs to do (in plain terms)

People open an integrations directory for one reason: to connect tools and keep them working without thinking about them every day. If the screen makes users guess what’s connected, what’s broken, or what to click next, trust drops fast.

With 3 integrations, a simple grid of logos can work. With 30, it falls apart: people stop scanning, support tickets go up, and the “Connect” button becomes a trap because each integration can be in a different state.

Every integration card (or row) should answer three questions at a glance:

- What is this? (Name plus a short purpose)

- Is it working right now? (Clear status plus last check or last sync)

- What do I do next? (Connect, continue setup, re-auth, manage)

Most confusion comes from edge cases that happen constantly in real teams. Someone connects Google with a personal account instead of the company one. A Stripe token expires and billing stops syncing. A Slack workspace is connected, but the required channel scope was never granted, so setup is “half done” even though the UI looks fine.

A good screen makes those situations obvious. Instead of just “Connected,” show something like “Connected (needs permission)” or “Connected to: [email protected],” and put the next step right on the card. That keeps people out of guesswork and keeps the list manageable as it grows.

A simple data model: catalog vs installs vs connections

The simplest way to scale an integrations directory is to separate:

- what you offer (the catalog)

- what each workspace enabled (installs)

- what external accounts or credentials are in use (connections)

This stays readable at 3 integrations and still works at 30.

The three core objects

An Integration is the catalog entry. It’s global, not tied to any workspace.

An Install represents a workspace enabling that Integration (for example: “Slack is turned on for Workspace A”).

A Connection represents a real external account or credential (for example: “Slack workspace X via OAuth” or “Stripe account Y via API key”). One Install can have many Connections.

A minimal set of fields that tends to scale well:

- Integration: id, key ("slack"), display_name, category, auth_type (oauth/api_key/webhook), docs_hint (short text), created_at

- Install: id, workspace_id, integration_id, status (enabled/disabled), setup_state (not_started/in_progress/complete), created_by, created_at, updated_at

- Connection: id, install_id, label ("Marketing Slack"), connection_status (ok/expired/error), external_account_id (if known), scopes/permissions_granted, last_success_at, created_at

Config vs secrets (and what must not leak)

Store user-visible config (selected channel, webhook URL nickname, enabled events) on the Install or Connection as plain data. Store secrets (OAuth refresh tokens, API keys, signing secrets) only in a secrets store or an encrypted field with strict access controls.

Don’t put secrets, full authorization codes, or raw webhook payloads into logs. If you have to log anything, log references (connection_id) plus safe metadata (HTTP status, error code).

To stay flexible across OAuth, API keys, and webhooks, keep auth-specific fields inside Connection (token metadata vs key fingerprint vs webhook verification status). Keep UI-facing state (enabled and setup progress) on Install.

Status and setup progress that users can understand

People open an integrations directory to answer three things quickly: is it working, how far along is setup, and what should I do next. If your status words are vague, support tickets go up and trust goes down.

Start with a small status set you can keep for years:

- Not set up

- In progress

- Connected

- Needs attention

- Disabled

Prefer derived status over stored status. Stored labels drift: someone fixes an error, but the badge stays red. Derived status is calculated from facts you already track, like whether tokens are valid, whether required setup steps are done, and whether an admin paused the integration. If you store anything, store the underlying facts (last successful sync, last error code), not the final label.

Setup progress works best as a short checklist, with a clear split between required and optional. Model it as step definitions (static, per integration) plus step results (per install).

Example: Slack might require “Authorize workspace” and “Select channels,” with an optional step like “Enable message previews.” The UI can show “2 of 3 required steps complete” while keeping optional items discoverable without blocking.

Multiple connections under one integration can turn a directory into a mess if you don’t plan for it. Keep one card per integration, show connection count, and roll up status honestly. If any connection is broken, surface “Needs attention” with a hint like “1 of 4 workspaces needs re-auth.” The overview stays clean, but it still reflects reality.

Permissions and roles without making it complicated

Integrations permissions get messy when everything is treated as one switch. It’s clearer to separate:

- who can view an integration

- who can configure it

- who can use it day to day

Start with a lightweight role check that applies everywhere. For many apps, three roles are enough: Admin, Manager, and Member. Admins can do anything. Managers can set up most integrations for their team. Members can use already-enabled integrations, but can’t change settings.

Then add per-integration permission flags only where they matter. Most integrations (calendar, chat) can follow default role rules. Sensitive ones (payments, payroll, exports) should require an extra check such as “Payments admin” or “Billing manager.” Keep this as a simple boolean on the integration install, not a whole new role system.

A mapping that stays readable:

- View: Admin, Manager, Member

- Configure: Admin, Manager (Members can see it but can’t connect or edit)

- Use: Anyone in the workspace once enabled (unless restricted)

- Sensitive override: Only users with a specific flag can configure or trigger actions

Audit doesn’t need to be heavy, but it should exist. Track enough to answer support and security questions quickly: who connected it, when credentials changed, and who disabled it. An “Activity” panel on the details page with 5 to 20 recent events is usually enough.

Example: Stripe might be visible to everyone, but only Admins (or users marked “Billing manager”) can connect it, rotate keys, or disable payouts. Slack might allow Managers to connect, while Members can still receive Slack notifications once it’s enabled.

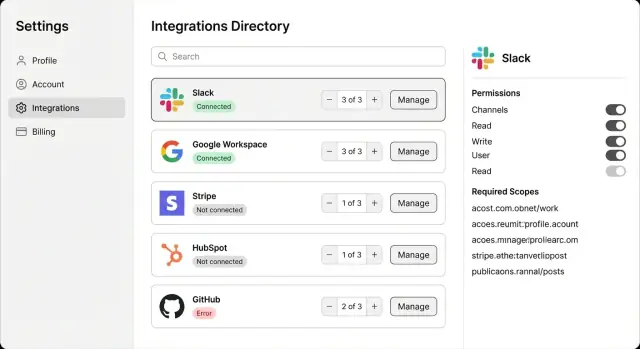

UI layout that still works at 30 integrations

With 3 integrations, you can show everything. With 30, the directory has to answer one question fast: “Which ones are working, and what should I do next?” The cleanest approach is to separate scanning from doing.

Keep the directory view focused on quick decisions. Push heavier controls into a detail page behind a single “Manage” button.

In the list, show only what supports the next click:

- Icon, name, and a one-line description (keep the length consistent)

- A clear status pill (Connected, Needs setup, Error, Disabled)

- One primary action button

- A secondary “Manage” button for everything else

Card anatomy matters because it builds muscle memory. The primary action should always mean “the next step” based on state: Connect for new, Continue setup for partial, Reconnect when auth expired, and Manage when everything is healthy. Avoid two equally loud buttons on every card. It makes the page feel noisy.

Example:

- If “Google” is Connected, the primary action can be Manage.

- If “Slack” failed last night, show Error and make the primary action Reconnect.

- If “Stripe” is half done, show Needs setup and Continue setup.

Empty states should guide without dumping a manual onto the screen:

- No integrations installed: suggest 2 to 3 popular picks and what they unlock

- No results for search: offer a simple tip like “try ‘CRM’ or ‘billing’”

- First-time setup: one sentence about permissions and what data will be accessed

This keeps the page calm at 30 integrations because every card answers: what is it, is it okay, and what do I do now?

The details page: setup flow, connections, and controls

Build the directory you described

Draft an integrations directory plan and turn it into a working app with Koder.ai.

The directory list gets people to the right integration. The details page is where they decide: set it up, fix it, or turn it off. Keep the page structure consistent across every integration, even when the backend work differs.

Start with a compact overview: integration name, a one-line description, and clear status labels (Connected, Needs attention, Disabled). Add a small “Setup progress” line so users know whether they’re one step from done or still at the start.

A setup flow that feels safe

A simple wizard works well: 3 to 6 steps, one screen at a time, with “Back” always available. Name steps in plain language (Connect account, Choose workspace, Pick data to sync, Confirm). If a step has optional choices, label them as optional instead of hiding them.

If setup can be paused, say so plainly: “You can finish later. We’ll keep your choices.” That reduces the fear of clicking away.

Connections and controls users won’t regret

Show Connections as a small table: account name, connected by (user), created date, and last sync.

For “next sync,” avoid promises you can’t keep (like exact times). Use wording you can stand behind, such as “Next sync: scheduled soon” or “Next sync: within the next hour,” based on what your system can actually guarantee.

Keep risky actions away from the main path. Put primary actions at the top (Continue setup, Reconnect). Put Disable and Disconnect in a separate “Danger zone” section at the bottom with a short explanation of impact. If you support roles, say it in one sentence (for example, “Only admins can disconnect”).

Add a small activity log: recent events (connected, token refreshed, sync failed), timestamps, and a short error message users can copy into a support ticket.

Step-by-step: add a new integration end to end

Adding an integration is easier when you treat it like a small product. It needs a listing, a way to connect, a place to store the connection, and clear outcomes for success or failure.

1) Start with the catalog entry

Add the integration to your catalog so it appears in the directory even before anyone connects it. Include a clear name, short description, icon, and one or two categories (Messaging, Payments). Write setup expectations in plain words, like “Connect an account” and “Choose a workspace.” This is also where you define what the integration will need later (OAuth scopes, required fields, supported features).

2) Build the connection method

Pick the simplest connection that matches the provider:

- OAuth when users must sign in and approve access (common for Google, Slack)

- API key when a user can paste a token from the provider

- Webhooks when the provider pushes events into your app

3) Save credentials and create a Connection record

When the user completes the flow, create a Connection record tied to their workspace or account, not just the user. Store credentials safely (encrypt at rest and avoid showing the full secret again). Save the basics you’ll need for support: provider account ID, created time, who connected it, and what permissions were granted.

4) Run a first-time check and set status + progress

Run a simple test right away (for Stripe: fetch account details). If it passes, show Connected and mark progress as ready. If it partially passes (connected but missing permission), mark it as Needs attention and point to the exact fix.

5) Decide what users see when it fails

Show one clear message, one recommended action, and a safe fallback. For example: “We couldn’t reach Stripe. Check the API key or try again.” Keep the directory usable even when one integration is broken.

If you’re building on Koder.ai (koder.ai), you can draft the catalog, setup flow, and status rules in Planning Mode first, then generate the UI and backend from that plan.

Errors, retries, and support-friendly history

Keep permissions simple and safe

Add roles and sensitive overrides without building a complicated permission system.

Integrations fail for boring reasons. If your directory can’t explain those reasons clearly, users blame your app and support has nothing to work with.

Group failures into buckets that match real fixes: login expired, missing permission, provider outage, or rate limit. Keep internal error codes detailed, but show users a short label they can understand.

When something breaks, the message should answer three things: what happened, what the user should do, and what your system will do next. Example: “Slack connection expired. Reconnect to continue syncing. We’ll retry automatically once you reconnect.” That’s calmer and more actionable than a raw API error.

Retry rules that don’t annoy people

Auto-retry only when the user can’t fix it themselves. A simple rule set is enough:

- Provider down or network error: auto-retry with backoff, keep the last success time

- Rate limited: pause, retry later, and show “Paused (rate limit)”

- Auth expired: stop retries and ask the user to reconnect

- Missing permissions: stop and show exactly which permission is needed

- Bad configuration: stop and point to the setting that must be filled in

Statuses go stale unless you refresh them. Add a lightweight health check job that periodically confirms tokens still work, the last sync ran, and the directory badge matches reality.

History that support can use

Keep a small event history per install. You don’t need full logs, just enough breadcrumbs: timestamp, event (“token refreshed”, “sync failed”), short reason, and who triggered it (user or system). Add an internal-only notes field so support can record what they changed and why.

Search, filters, and organizing the directory

A directory gets messy fast once you pass a handful of apps. The goal is simple: help people find what they need in seconds, and help them spot problems without opening every card.

Start with basic search over integration name and category. Most users type what they already know (“Slack”, “Stripe”), so name matching matters more than fancy ranking. Category search helps when they only know the job (payments, messaging).

Filters should mirror real intent. These three usually cover most use cases:

- Connected (working now)

- Needs attention (errors, expired token, missing permission)

- Not set up (available but no install yet)

For organizing the list, pick one primary grouping and stick to it. Category grouping works well at higher counts (CRM, Payments, Messaging). Popularity can be useful too, but only if it reflects your user base, not marketing. A practical default: show the most used first, then group the rest by category.

You also need a clean plan for “not everyone should see everything.” If an integration is behind a feature flag or a plan tier, either hide it for most users or show it disabled with a short reason like “Business plan.” Avoid showing a page full of greyed-out cards. It makes the screen feel broken.

Keep performance snappy by treating list and details as separate loads. Paginate or virtualize the list so you aren’t rendering 30 heavy cards at once, and lazy-load details only when a user opens an integration. The directory can show summary fields (Slack: Connected, Google: Needs attention, Stripe: Not set up) while the details page fetches full connection history.

Example: Slack, Google, and Stripe in a real app

Imagine a team workspace app called Pinework. It has two roles: Admin and Member. Admins can connect tools and change settings. Members can use connected tools but can’t add or remove them.

In Pinework’s integrations directory, each card shows a clear label (Connected, Needs setup, Error), a short “what it does” line, and setup progress like “2 of 3 steps.” People can tell what works and what’s pending without clicking around.

Slack is used for notifications. An Admin opens Slack and sees: Status: Connected, Setup: “3 of 3 steps.” Members see Slack too, but the main action is disabled and reads “Ask an Admin to manage.” If Slack disconnects, Members can still see what broke, but not the reconnect controls.

Google is used for calendars. Pinework supports two departments, so it allows multiple connections. The Google card shows: Status: Connected (2 accounts). Under it, a short line lists “Marketing Calendar” and “Support Calendar.” Setup can still be complete, and the details page shows two separate connections so an Admin can revoke just one.

Stripe is used for billing. A common partial setup is: the account is connected, but webhooks aren’t finished. The card shows: Status: Needs setup, Progress: “2 of 3 steps,” with a warning like “Payments may not sync.” The details view makes the remaining step explicit:

- Connect Stripe account (done)

- Choose billing plan mapping (done)

- Add webhook endpoint (not done)

That avoids the painful “it looks connected but nothing works” situation.

Common mistakes that make integrations hard to manage

Build and earn along the way

Earn credits by sharing what you built with Koder.ai or inviting teammates to try it.

An integrations directory usually breaks when an app grows from a few integrations to dozens. The problems are rarely “big tech.” They’re small labeling and modeling mistakes that confuse people every day.

A common issue is mixing up “installed” vs “connected.” Installed usually means “available in your workspace.” Connected means real credentials exist and data can flow. When those blur together, users click an integration that looks ready and hit a dead end.

Another mistake is inventing too many status states. Teams start with a simple badge, then add edge cases: pending, verifying, partial, paused, degraded, blocked, expiring, and more. Over time, those labels drift from reality because nobody keeps them consistent. Keep a small set tied to checks you can actually run, like Not connected, Connected, Needs attention.

Hidden permissions cause trouble too. Someone connects an account, then later discovers the integration had broader access than expected. Make the scope obvious before the final “Connect” step, and show it again on the details page so admins can audit it.

Don’t assume one connection per integration

Many apps need multiple connections: two Slack workspaces, several Stripe accounts, or a shared Google account plus personal accounts. If you hardcode “one integration = one connection,” you’ll end up with ugly workarounds later.

Plan for:

- Multiple connections under one integration

- A clear “default” connection (if needed)

- Shared vs personal connections

- A place to see who connected it

Keep the directory list view lightweight. When you stuff it with logs, field mappings, and long descriptions, scanning slows down. Use the list for name, short purpose, and setup progress. Put history and advanced settings on the integration details page.

Quick checklist and next steps

A scalable integrations directory comes down to a simple model and an honest UI. If users can answer three questions quickly, the system feels predictable: what’s connected, what’s broken, and what should I do next?

Checklist before shipping:

- Separate the model: Integration (catalog) vs Install (enabled in this workspace) vs Connection (OAuth token, API key, or webhook). Add Event only if you need audit and support history.

- Derive status: compute labels from checks (token valid, scopes OK, webhook reachable) plus setup steps completed, so badges stay accurate.

- Keep list view scannable: each row shows name, a clear status label, and one “next action” (Connect, Continue, Reconnect, Fix permissions).

- Make lifecycle actions first-class: Connect, Continue setup, Reconnect, Disable, and Disconnect should be easy to find, with short confirmations.

- Make permissions visible and auditable: show who can connect or disconnect, and record who changed what and when.

Next, pick three integrations you already know well and model them end to end: a chat tool (OAuth), a Google-style account connection (OAuth with scopes), and a payments tool (API key plus webhooks). If your model can express all three without special cases, it will usually scale to 30.

FAQ

What’s the one job an integrations directory screen should do?

Treat it as a control panel, not a marketing page. Each card should quickly show what the integration is for, whether it’s working right now, and the single next action the user should take. If users need to click just to learn “is this connected?”, the directory will feel unreliable as it grows.

What should every integration card show at a glance?

A simple rule is: one integration card should answer “what is it,” “is it healthy,” and “what now.” That usually means a name plus one-line purpose, a status with a recent timestamp (last sync or last check), and one primary button that changes based on state. Keep everything else behind “Manage” so scanning stays fast.

Why split the data model into Integration, Install, and Connection?

Separate what you offer from what a workspace enabled and what credentials exist. Use a global Integration (catalog entry), an Install (enabled in a workspace), and a Connection (actual OAuth account, API key, or webhook). This prevents the common mess where “installed” and “connected” get mixed up and users can’t tell what’s real.

How do I handle integrations that need multiple connected accounts?

Because real teams often need more than one external account for the same provider. Marketing and Support may connect different Google calendars, or a company may have multiple Stripe accounts. Modeling multiple Connections under one Install keeps the directory clean while still letting admins manage accounts individually on the details page.

What status labels should I use so they don’t become confusing later?

Use a small set of labels you can keep consistent, like Not set up, In progress, Connected, Needs attention, and Disabled. Then derive those labels from facts you can check, such as token validity, required setup steps completed, and last successful sync. This avoids stale badges that stay red after the issue is already fixed.

How should I model and show setup progress without building a huge wizard?

Make setup progress a short checklist of required steps, plus optional steps that don’t block completion. Store the step definitions per integration and the step results per install, so the UI can say something like “2 of 3 required steps complete.” Users should always see the next missing required step without digging.

How do I keep integration permissions simple but safe?

Start with a simple role rule that applies everywhere, then add extra checks only for sensitive integrations. For many products, Admins can configure, Managers can configure most tools, and Members can use enabled tools but can’t connect or change settings. For payments or payroll, add a single “billing/payments admin” flag rather than inventing a whole new role system.

Where should I store OAuth tokens and API keys, and what should never go in logs?

Keep user-visible config as normal data, but store secrets like refresh tokens and API keys in a secrets store or encrypted fields with strict access control. Don’t log raw secrets, authorization codes, or webhook payloads; log safe metadata and references like a connection ID instead. This reduces risk and makes compliance and support easier.

How should the UI handle errors like expired tokens, outages, and missing permissions?

Show an error message that tells the user what happened, what they should do next, and what your system will do automatically. Retries should be quiet and limited to things the user can’t fix, like temporary outages or rate limits. For expired auth or missing permissions, stop retrying and make “Reconnect” or “Fix permissions” the primary action.

What’s the easiest way to add search, filters, and keep the directory usable at 30+ integrations?

Keep search simple and focused on how users think: provider name first, then category. Add filters that match intent, like Connected, Needs attention, and Not set up, so people can find problems quickly. If you’re building in Koder.ai, draft the catalog fields, status rules, and setup steps in Planning Mode first so the generated UI and backend stay consistent as you add more integrations.