May 14, 2025·8 min

Intel, x86 Dominance, and Why Platform Shifts Are So Hard

A clear history of how Intel x86 built decades of compatibility, why ecosystems get locked in, and why shifting platforms is so hard for the industry.

A clear history of how Intel x86 built decades of compatibility, why ecosystems get locked in, and why shifting platforms is so hard for the industry.

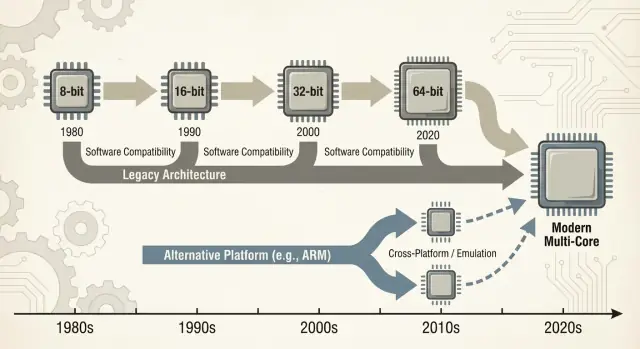

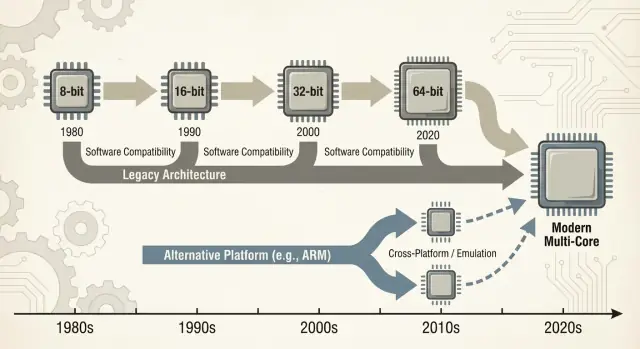

When people say “x86,” they usually mean a family of CPU instructions that started with Intel’s 8086 chip and evolved over decades. Those instructions are the basic verbs a processor understands—add, compare, move data, and so on. That instruction set is called an ISA (instruction set architecture). You can think of the ISA as the “language” software ultimately has to speak to run on a given type of CPU.

x86: The most common ISA used in PCs for most of the last 40 years, implemented primarily by Intel and also by AMD.

Backward compatibility: The ability for newer computers to keep running older software (sometimes even decades-old programs) without requiring major rewrites. It’s not perfect in every case, but it’s a guiding promise of the PC world: “Your stuff should still work.”

“Dominance” here isn’t just a bragging-rights claim about performance. It’s a practical, compounding advantage across several dimensions:

That combination matters because each layer reinforces the others. More machines encourages more software; more software encourages more machines.

Switching away from a dominant ISA isn’t like swapping one component for another. It can break—or at least complicate—applications, drivers (for printers, GPUs, audio devices, niche peripherals), developer toolchains, and even day-to-day habits (imaging processes, IT scripts, security agents, deployment pipelines). Many of those dependencies stay invisible until something fails.

This post focuses mainly on PCs and servers, where x86 has been the default for a long time. We’ll also reference recent shifts—especially ARM transitions—because they provide modern, easy-to-compare lessons about what changes smoothly, what doesn’t, and why “just recompile it” is rarely the whole story.

The early PC market didn’t start with a grand architectural plan—it started with practical constraints. Businesses wanted machines that were affordable, available in volume, and easy to service. That pushed vendors toward CPUs and parts that could be sourced reliably, paired with standard peripherals, and assembled into systems without custom engineering.

IBM’s original PC design leaned heavily on off-the-shelf components and a relatively inexpensive Intel 8088-class processor. That choice mattered because it made the “PC” feel less like a single product and more like a recipe: a CPU family, a set of expansion slots, a keyboard/display approach, and a software stack that could be reproduced.

Once the IBM PC proved there was demand, the market expanded through cloning. Companies such as Compaq showed that you could build compatible machines that ran the same software—and sell them at different price points.

Just as important was second-source manufacturing: multiple suppliers could provide compatible processors or components. For buyers, that reduced the risk of betting on a single vendor. For OEMs, it increased supply and competition, which accelerated adoption.

In that environment, compatibility became the feature people understood and valued. Buyers didn’t need to know what an instruction set was; they only needed to know whether Lotus 1-2-3 (and later Windows applications) would run.

Software availability quickly turned into a simple purchasing heuristic: if it runs the same programs as other PCs, it’s a safe choice.

Hardware and firmware conventions did a lot of invisible work. Common buses and expansion approaches—along with BIOS/firmware expectations and shared system behaviors—made it easier for hardware makers and software developers to target “the PC” as a stable platform.

That stability helped cement x86 as the default foundation under a growing ecosystem.

x86 didn’t win purely because of clock speeds or clever chips. It won because software followed users, and users followed software—an economic “network effect” that compounds over time.

When a platform gains an early lead, developers see a bigger audience and a clearer path to revenue. That produces more applications, better support, and more third‑party add-ons. Those improvements make the platform even more attractive to the next wave of buyers.

Repeat that loop for years and the “default” platform becomes hard to displace—even if alternatives are technically appealing.

This is why platform transitions aren’t just about building a CPU. They’re about recreating an entire ecosystem: apps, installers, update channels, peripherals, IT processes, and the collective know-how of millions of users.

Businesses often keep critical applications for a long time: custom databases, internal tools, ERP add-ons, industry-specific software, and workflow macros that nobody wants to touch because they “just work.” A stable x86 target meant:

Even if a new platform promised lower costs or better performance, the risk of breaking a revenue-generating workflow often outweighed the upside.

Developers rarely optimize for the “best” platform in a vacuum. They optimize for the platform that minimizes support burden and maximizes reach.

If 90% of your customers are on x86 Windows, that’s where you test first, where you ship first, and where you fix bugs fastest. Supporting a second architecture can mean extra build pipelines, more QA matrices, more “it works on my machine” debugging, and more customer support scripts.

The result is a self-reinforcing gap: the leading platform tends to get better software, faster.

Imagine a small business. Their accounting package is x86-only, integrated with a decade of templates and a plug-in for payroll. They also rely on a specific label printer and a document scanner with finicky drivers.

Now propose a platform switch. Even if the core apps exist, the edge pieces matter: the printer driver, the scanner utility, the PDF plugin, the bank-import module. Those “boring” dependencies become must-haves—and when they’re missing or flaky, the whole migration stalls.

That’s the flywheel in action: the winning platform accumulates the long tail of compatibility that everyone quietly depends on.

Backward compatibility wasn’t just a nice feature of x86—it became a deliberate product strategy. Intel kept the x86 instruction set architecture (ISA) stable enough that software written years earlier could still run, while changing almost everything underneath.

The key distinction is what stayed compatible. The ISA defines the machine instructions programs rely on; microarchitecture is how a chip executes them.

Intel could move from simpler pipelines to out‑of‑order execution, add larger caches, improve branch prediction, or introduce new fabrication processes—without asking developers to rewrite their apps.

That stability created a powerful expectation: new PCs should run old software on day one.

x86 accumulated new capabilities in layers. Instruction set extensions like MMX, SSE, AVX, and later features were additive: old binaries still worked, and newer apps could detect and use new instructions when available.

Even major transitions were smoothed by compatibility mechanisms:

The downside is complexity. Supporting decades of behavior means more CPU modes, more edge cases, and a heavier validation burden. Every new generation must prove it still runs yesterday’s business app, driver, or installer.

Over time, “don’t break existing apps” stops being a guideline and turns into a strategic constraint: it protects the installed base, but it also makes radical platform changes—new ISAs, new system designs, new assumptions—far harder to justify.

“Wintel” wasn’t just a catchy label for Windows and Intel chips. It described a self-reinforcing loop where each part of the PC industry benefited from sticking to the same default target: Windows on x86.

For most consumer and business software vendors, the practical question wasn’t “what’s the best architecture?” but “where are the customers, and what will support calls look like?”

Windows PCs were widely deployed in homes, offices, and schools, and they were largely x86-based. Shipping for that combo maximized reach while minimizing surprises.

Once a critical mass of applications assumed Windows + x86, new buyers had another reason to choose it: their must-have programs already worked there. That, in turn, made the platform even more attractive for the next wave of developers.

PC makers (OEMs) succeed when they can build many models quickly, source components from multiple suppliers, and ship machines that “just work.” A common Windows + x86 baseline simplified that.

Peripheral companies followed the volume. If most buyers used Windows PCs, then printers, scanners, audio interfaces, Wi‑Fi chips, and other devices would prioritize Windows drivers first. Better driver availability improved the Windows PC experience, which helped OEMs sell more units, which kept the volume high.

Corporate and government purchasing tends to reward predictability: compatibility with existing apps, manageable support costs, vendor warranties, and proven deployment tools.

Even when alternatives were appealing, the lowest-risk choice often won because it reduced training, avoided edge-case failures, and fit established IT processes.

The result was less a conspiracy than a set of aligned incentives—each participant choosing the path that reduced friction—creating momentum that made platform change unusually hard.

A “platform transition” isn’t just swapping one CPU for another. It’s a bundle move: the CPU instruction set architecture (ISA), the operating system, the compiler/toolchain that builds apps, and the driver stack that makes hardware work. Change any one of those and you often disturb the others.

Most breakage isn’t dramatic “the app won’t launch” failure. It’s death by a thousand paper cuts:

Even if the core application has a new build, its surrounding “glue” may not.

Printers, scanners, label makers, specialized PCIe/USB cards, medical devices, point-of-sale gear, and USB dongles live and die by drivers. If the vendor is gone—or just uninterested—there may be no driver for the new OS or architecture.

In many businesses, one $200 device can freeze a fleet of $2,000 PCs.

The biggest blocker is often “small” internal tools: a custom Access database, an Excel macro workbook, a VB app written in 2009, a niche manufacturing utility used by three people.

These aren’t on anyone’s product roadmap, but they’re mission-critical. Platform shifts fail when the long tail doesn’t get migrated, tested, and owned by someone.

A platform shift isn’t judged only on benchmarks. It’s judged on whether the total bill—money, time, risk, and lost momentum—stays below the perceived benefit. For most people and organizations, that bill is higher than it looks from the outside.

For users, switching costs start with the obvious (new hardware, new peripherals, new warranties) and quickly move into the messy stuff: retraining muscle memory, reconfiguring workflows, and revalidating the tools they rely on daily.

Even when an app “runs,” the details can change: a plug-in doesn’t load, a printer driver is missing, a macro behaves differently, a game anti-cheat flags something, or a niche accessory stops working. Each one is minor; together they can erase the value of the upgrade.

Vendors pay for platform shifts through a ballooning test matrix. It’s not just “does it launch?” It’s:

Every extra combination adds QA time, more documentation to maintain, and more support tickets. A transition can turn a predictable release train into a permanent incident-response cycle.

Developers absorb the cost of porting libraries, rewriting performance-critical code (often hand-tuned for an ISA), and rebuilding automated tests. The hardest part is restoring confidence: proving that the new build is correct, fast enough, and stable under real workloads.

Migration work competes directly with new features. If a team spends two quarters making things merely “work again,” that’s two quarters they didn’t spend improving the product.

Many organizations will only switch when the old platform blocks them—or when the new one is so compelling it justifies that trade.

When a new CPU architecture arrives, users don’t ask about instruction sets—they ask whether their apps still open. That’s why “bridges” matter: they let new machines run old software long enough for the ecosystem to catch up.

Emulation imitates an entire CPU in software. It’s the most compatible option, but usually the slowest because every instruction is “acted out” rather than executed directly.

Binary translation (often dynamic) rewrites chunks of x86 code into the new CPU’s native instructions while the program runs. This is how many modern transitions ship a day-one story: install your existing apps, and a compatibility layer quietly translates.

The value is simple: you can buy new hardware without waiting for every vendor to recompile.

Compatibility layers tend to work best for mainstream, well-behaved applications—and struggle at the edges:

Hardware support is often the real blocker.

Virtualization helps when you need a whole legacy environment (a specific Windows version, an old Java stack, a line-of-business app). It’s clean operationally—snapshots, isolation, easy rollback—but it depends on what you’re virtualizing.

Same-architecture VMs can be near-native; cross-architecture VMs usually fall back to emulation and slow down.

A bridge is usually sufficient for office apps, browsers, and everyday productivity—where “fast enough” wins. It’s riskier for:

In practice, bridges buy time—but they rarely eliminate the migration work.

Arguments about CPUs often sound like a single scoreboard: “faster wins.” In reality, platforms win when they match the constraints of the devices and the workloads people actually run.

x86 became the default for PCs partly because it delivered strong peak performance on wall power, and because the industry built everything else around that assumption.

Desktop and laptop buyers historically rewarded snappy interactive performance: launching apps, compiling code, gaming, heavy spreadsheets. That pushes vendors toward high boost clocks, wide cores, and aggressive turbo behavior—great when you can spend watts freely.

Power efficiency is a different game. If your product is limited by battery, heat, fan noise, or a thin chassis, the best CPU is the one that does “enough” work per watt, consistently, without throttling.

Efficiency isn’t just about saving energy; it’s about staying within thermal limits so performance doesn’t collapse after a minute.

Phones and tablets live inside tight power envelopes and have always been cost-sensitive at massive volume. That environment rewarded designs optimized around efficiency, integrated components, and predictable thermal behavior.

It also created an ecosystem where the operating system, apps, and silicon evolved together under mobile-first assumptions.

In data centers, a CPU choice is rarely a pure benchmark decision. Operators care about reliability features, long support windows, stable firmware, monitoring, and a mature ecosystem of drivers, hypervisors, and management tools.

Even when a new architecture looks attractive on perf/watt, the risk of operational surprises can outweigh the upside.

Modern server workloads are diverse: web serving favors high throughput and efficient scaling; databases reward memory bandwidth, latency consistency, and proven tuning practices; AI increasingly shifts value to accelerators and software stacks.

As the mix changes, the winning platform can change too—but only if the surrounding ecosystem can keep up.

A new CPU architecture can be technically excellent and still fail if the day-to-day tools don’t make it easy to build, ship, and support software. For most teams, “platform” isn’t just the instruction set—it’s the whole delivery pipeline.

Compilers, debuggers, profilers, and core libraries quietly shape developer behavior. If the best compiler flags, stack traces, sanitizers, or performance tools arrive late (or behave differently), teams hesitate to bet releases on them.

Even small gaps matter: a missing library, a flaky debugger plugin, or a slower CI build can turn “we could port this” into “we won’t this quarter.” When the x86 toolchain is the default in IDEs, build systems, and continuous integration templates, the path of least resistance keeps pulling developers back.

Software reaches users through packaging conventions: installers, updaters, repositories, app stores, containers, and signed binaries. A platform shift forces uncomfortable questions:

If distribution gets messy, support costs spike—and many vendors will avoid it.

Businesses buy platforms they can manage at scale: imaging, device enrollment, policies, endpoint security, EDR agents, VPN clients, and compliance reporting. If any of those tools lag on a new architecture, pilots stall.

“Works on my machine” is irrelevant if IT can’t deploy and secure it.

Developers and IT converge on one practical question: how fast can we ship and support? Tooling and distribution often answer it more decisively than raw benchmarks.

One practical way teams reduce migration friction is by shortening the time between an idea and a testable build—especially when validating the same application across different environments (x86 vs. ARM, different OS images, or different deployment targets).

Platforms like Koder.ai fit into this workflow by letting teams generate and iterate on real applications through a chat interface—commonly producing React-based web frontends, Go backends, and PostgreSQL databases (plus Flutter for mobile). For platform-transition work, two capabilities are particularly relevant:

Because Koder.ai supports source code export, it can also serve as a bridge between experimentation and a conventional engineering pipeline—useful when you need to move quickly, but still end up with maintainable code under your own control.

ARM’s push into laptops and desktops is a useful reality check on how hard platform transitions really are. On paper, the pitch is simple: better performance per watt, quieter machines, longer battery life.

In practice, success hinges less on the CPU core and more on everything wrapped around it—apps, drivers, distribution, and who has the power to align incentives.

Apple’s move from Intel to Apple Silicon worked largely because Apple controls the full stack: hardware design, firmware, operating system, developer tools, and primary app distribution channels.

That control let the company make a clean break without waiting for dozens of independent partners to move in sync.

It also enabled a coordinated “bridge” period: developers got clear targets, users got compatibility paths, and Apple could keep pressure on key vendors to ship native builds. Even when some apps weren’t native, the user experience often stayed acceptable because the transition plan was designed as a product, not just a processor swap.

Windows-on-ARM shows the other side of the coin. Microsoft doesn’t fully control the hardware ecosystem, and Windows PCs depend heavily on OEM choices and a long tail of device drivers.

That creates common failure points:

ARM’s recent progress reinforces a core lesson: controlling more of the stack makes transitions faster and less fragmented.

When you rely on partners, you need unusually strong coordination, clear upgrade paths, and a reason for every participant—chip vendor, OEM, developer, and IT buyer—to move at the same time.

Platform shifts fail for boring reasons: the old platform still works, everyone already paid for it (in money and habits), and the “edge cases” are where real businesses live.

A new platform tends to win only when three things line up:

First, the benefit is obvious to normal buyers—not just engineers: better battery life, materially lower costs, new form factors, or a step-change in performance for common tasks.

Second, there’s a believable compatibility plan: great emulation/translation, easy “universal” builds, and clear paths for drivers, peripherals, and enterprise tooling.

Third, incentives align across the chain: OS vendor, chip vendor, OEMs, and app developers all see upside and have a reason to prioritize the migration.

Successful transitions look less like a flip of a switch and more like controlled overlap. Phased rollouts (pilot groups first), dual builds (old + new), and telemetry (crash rates, performance, feature usage) let teams catch issues early.

Equally important: a published support window for the old platform, clear internal deadlines, and a plan for “can’t move yet” users.

x86 still has massive momentum: decades of compatibility, entrenched enterprise workflows, and broad hardware options.

But pressure keeps building from new needs—power efficiency, tighter integration, AI-focused compute, and simpler device fleets. The hardest battles aren’t about raw speed; they’re about making switching feel safe, predictable, and worth it.

x86 is a CPU instruction set architecture (ISA): the set of machine-language instructions software ultimately runs.

“Dominance” in this post means the compounding advantage of high shipment volume, the largest software catalog, and default mindshare—not just raw benchmark leadership.

An ISA is the “language” a CPU understands.

If an app is compiled for x86, it will run natively on x86 CPUs. If you switch to a different ISA (like ARM), you typically need a native rebuild, or you rely on translation/emulation to run the old binary.

Backward compatibility lets newer machines keep running older software with minimal changes.

In the PC world, it’s a product expectation: upgrades shouldn’t force you to rewrite apps, replace workflows, or abandon “that one legacy tool” that still matters.

They can change how a chip executes instructions (microarchitecture) while keeping the instructions themselves (the ISA) stable.

That’s why you can see big changes in performance, caches, and power behavior without breaking old binaries.

Common breakpoints include:

Often the “main app” works, but the surrounding glue doesn’t.

Because it’s usually the missing driver or unsupported peripheral that blocks the move.

A compatibility layer can translate an application, but it can’t conjure a stable kernel driver for a niche scanner, POS device, or USB security key if the vendor never shipped one.

Installed base drives developer effort.

If most customers are on Windows x86, vendors prioritize that build, test matrix, and support playbook. Supporting another architecture adds CI builds, QA combinations, documentation, and support burden, which many teams defer until demand is undeniable.

Not reliably.

Recompiling is just one piece. You may also need:

The hardest part is often proving the new build is correct and supportable in real environments.

They’re bridges, not cures:

They buy time while the ecosystem catches up, but drivers and low-level components remain hard limits.

Use a checklist-driven pilot:

Treat it as a controlled rollout with rollback options, not a single “big bang” swap.