Dec 26, 2025·8 min

Internal developer tools with Claude Code: safe CLI dashboards

Build internal developer tools with Claude Code to solve log search, feature toggles, and data checks while enforcing least privilege and clear guardrails.

What problem your internal tool should actually solve

Internal tools often begin as a shortcut: one command or one page that saves the team 20 minutes during an incident. The risk is that the same shortcut can quietly turn into a privileged backdoor if you don’t define the problem and boundaries up front.

Teams usually reach for a tool when the same pain repeats every day, for example:

- Log search that’s slow, inconsistent, or split across systems

- Feature toggles that require a risky manual edit or direct database write

- Data checks that depend on one person running a script from their laptop

- On-call tasks that are simple, but easy to mess up at 2 a.m.

These problems feel small until the tool can read production logs, query customer data, or flip a flag. Then you’re dealing with access control, audit trails, and accidental writes. A tool that is “just for engineers” can still cause an outage if it runs a broad query, hits the wrong environment, or changes state without a clear confirmation step.

Define success in narrow, measurable terms: faster operations without widening permissions. A good internal tool removes steps, not safeguards. Instead of giving everyone broad database access to check a suspected billing issue, build a tool that answers one question: “Show me today’s failed billing events for account X,” using read-only, scoped credentials.

Before you pick an interface, decide what people need in the moment. A CLI is great for repeatable tasks during on-call. A web dashboard is better when results need context and shared visibility. Sometimes you ship both, but only if they’re thin views over the same guarded operations. The goal is one well-defined capability, not a new admin surface area.

Choose a single pain and keep the scope small

The fastest way to make an internal tool useful (and safe) is to pick one clear job and do it well. If it tries to handle logs, feature flags, data fixes, and user management on day one, it will grow hidden behaviors and surprise people.

Start with a single question a user asks during real work. For example: “Given a request ID, show me the error and the surrounding lines across services.” That’s narrow, testable, and easy to explain.

Be explicit about who the tool is for. A developer debugging locally needs different options than someone on-call, and both differ from support or an analyst. When you mix audiences, you end up adding “powerful” commands that most users should never touch.

Write down inputs and outputs like a small contract.

Inputs should be explicit: request ID, time range, environment. Outputs should be predictable: matched lines, service name, timestamp, count. Avoid hidden side effects such as “also clears cache” or “also retries the job.” Those are the features that cause accidents.

Default to read-only. You can still make the tool valuable with search, diff, validate, and report. Add write actions only when you can name a real scenario that needs it and you can tightly constrain it.

A simple scope statement that keeps teams honest:

- One primary task, one primary screen or command

- One data source (or one logical view), not “everything”

- Explicit flags for environment and time range

- Read-only first, no background actions

- If writes exist, require confirmation and log every change

Map data sources and sensitive operations early

Before Claude Code writes anything, write down what the tool will touch. Most security and reliability problems show up here, not in the UI. Treat this mapping as a contract: it tells reviewers what is in scope and what is off limits.

Start with a concrete inventory of data sources and owners. For example: logs (app, gateway, auth) and where they live; the exact database tables or views the tool may query; your feature flag store and naming rules; metrics and traces and which labels are safe to filter on; and whether you plan to write notes to ticketing or incident systems.

Then name the operations the tool is allowed to perform. Avoid “admin” as a permission. Instead, define auditable verbs. Common examples include: read-only search and export (with limits), annotate (add a note without editing history), toggling specific flags with a TTL, bounded backfills (date range and record count), and dry-run modes that show impact without changing data.

Sensitive fields need explicit handling. Decide what must be masked (emails, tokens, session IDs, API keys, customer identifiers) and what can be shown only in truncated form. For example: show the last 4 characters of an ID, or hash it consistently so people can correlate events without seeing the raw value.

Finally, agree on retention and audit rules. If a user runs a query or flips a flag, record who did it, when, which filters were used, and the result count. Keep audit logs longer than app logs. Even a simple rule like “queries retained 30 days, audit records 1 year” prevents painful debates during an incident.

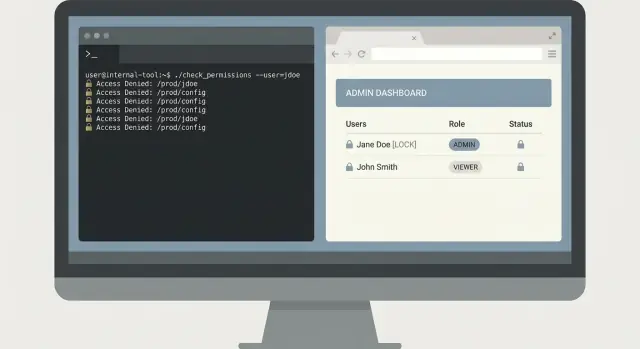

Least-privilege access model that stays simple

Least privilege is easiest when you keep the model boring. Start by listing what the tool can do, then label each action as either read-only or write. Most internal tools only need read access for most people.

For a web dashboard, use your existing identity system (SSO with OAuth). Avoid local passwords. For a CLI, prefer short-lived tokens that expire quickly and scope them to only the actions the user needs. Long-lived shared tokens tend to get pasted into tickets, saved in shell history, or copied to personal machines.

Keep RBAC small. If you need more than a few roles, the tool is probably doing too much. Many teams do well with three:

- Viewer: read-only, safe defaults

- Operator: read plus a small set of low-risk actions

- Admin: high-risk actions, used rarely

Separate environments early, even if the UI looks the same. Make it hard to “accidentally do prod.” Use different credentials per environment, different config files, and different API endpoints. If a user only supports staging, they shouldn’t even be able to authenticate against production.

High-risk actions deserve an approval step. Think deleting data, changing feature flags, restarting services, or running heavy queries. Add a second-person check when the blast radius is large. Practical patterns include typed confirmations that include the target (service name and environment), recording who requested and who approved, and adding a short delay or scheduled window for the most dangerous operations.

If you’re generating the tool with Claude Code, make it a rule that every endpoint and command declares its required role up front. That one habit keeps permissions reviewable as the tool grows.

Guardrails that prevent accidents and bad queries

Go from dev to deployed

Deploy and host your internal tool when you are ready to share it with the team.

The most common failure mode for internal tools isn’t an attacker. It’s a tired teammate running the “right” command with the wrong inputs. Treat guardrails as product features, not polish.

Safety defaults

Start with a safe stance: read-only by default. Even if the user is an admin, the tool should open in a mode that can only fetch data. Make write actions opt-in and obvious.

For any operation that changes state (toggle a flag, backfill data, delete a record), require explicit type-to-confirm. “Are you sure? y/N” is too easy to muscle-memory. Ask the user to retype something specific, like the environment name plus the target ID.

Tight input validation prevents most disasters. Accept only the shapes you truly support (IDs, dates, environments) and reject everything else early. For searches, constrain power: cap result limits, enforce sane date ranges, and use an allow-list approach rather than letting arbitrary patterns hit your log store.

To avoid runaway queries, add timeouts and rate limits. A safe tool fails fast and explains why, rather than hanging and hammering your database.

A guardrail set that works well in practice:

- Default to read-only, with a clear “write mode” switch

- Type-to-confirm for writes (include env + target)

- Strict validation for IDs, dates, limits, and allowed patterns

- Query timeouts plus per-user rate limits

- Secret masking in output and in the tool’s own logs

Output hygiene

Assume the tool’s output will be copied into tickets and chat. Mask secrets by default (tokens, cookies, API keys, and emails if needed). Also scrub what you store: audit logs should record what was attempted, not the raw data returned.

For a log search dashboard, return a short preview and a count, not full payloads. If someone truly needs the full event, make it a separate, clearly gated action with its own confirmation.

How to work with Claude Code without losing control

Treat Claude Code like a fast junior teammate: helpful, but not a mind reader. Your job is to keep the work bounded, reviewable, and easy to undo. That’s the difference between tools that feel safe and tools that surprise you at 2 a.m.

Start with a spec the model can follow

Before you ask for code, write a tiny spec that names the user action and the expected outcome. Keep it about behavior, not framework trivia. A good spec usually fits on half a page and covers:

- Commands or screens (exact names)

- Inputs (flags, fields, formats, limits)

- Outputs (what shows up, what gets saved)

- Error cases (invalid input, timeouts, empty results)

- Permission checks (what happens when access is denied)

For example, if you’re building a log search CLI, define one command end-to-end: logs search --service api --since 30m --text "timeout", with a hard cap on results and a clear “no access” message.

Ask for small increments you can verify

Request a skeleton first: CLI wiring, config loading, and a stubbed data call. Then ask for exactly one feature completed all the way (including validation and errors). Small diffs make reviews real.

After each change, ask for a plain-language explanation of what changed and why. If the explanation doesn’t match the diff, stop and restate the behavior and the safety constraints.

Generate tests early, before you add more features. At minimum, cover the happy path, invalid inputs (bad dates, missing flags), permission denied, empty results, and rate limit or backend timeouts.

CLI vs web dashboard: picking the right interface

A CLI and an internal web dashboard can solve the same problem, but they fail in different ways. Choose the interface that makes the safe path the easiest path.

A CLI is usually best when speed matters and the user already knows what they want. It also fits read-only workflows well, because you can keep permissions narrow and avoid buttons that accidentally trigger write actions.

A CLI is a strong choice for fast on-call queries, scripts and automation, explicit audit trails (every command is spelled out), and low overhead rollout (one binary, one config).

A web dashboard is better when you need shared visibility or guided steps. It can reduce mistakes by nudging people toward safe defaults like time ranges, environments, and pre-approved actions. Dashboards also work well for team-wide status views, guarded actions that require confirmation, and built-in explanations of what a button does.

When possible, use the same backend API for both. Put auth, rate limits, query limits, and audit logging in that API, not in the UI. Then the CLI and dashboard become different clients with different ergonomics.

Also decide where it runs, because that changes your risk. A CLI on a laptop can leak tokens. Running it on a bastion host or in an internal cluster can reduce exposure and make logs and policy enforcement easier.

Example: for log search, a CLI is great for an on-call engineer pulling the last 10 minutes for one service. A dashboard is better for a shared incident room where everyone needs the same filtered view, plus a guided “export for postmortem” action that is permission-checked.

A realistic example: log search tool for on-call

Build the first safe tool

Turn your scoped CLI or dashboard spec into working code through a simple chat.

It’s 02:10 and on-call gets a report: “Clicking Pay sometimes fails for one customer.” Support has a screenshot with a request ID, but no one wants to paste random queries into a log system with admin permissions.

A small CLI can solve this safely. The key is to keep it narrow: find the error fast, show only what’s needed, and leave production data unchanged.

A minimal CLI flow

Start with one command that forces time bounds and a specific identifier. Require a request ID and a time window, and default to a short window.

oncall-logs search --request-id req_123 --since 30m --until now

Return a summary first: service name, error class, count, and the top 3 matching messages. Then allow an explicit expand step that prints full log lines only when the user asks.

oncall-logs show --request-id req_123 --limit 20

This two-step design prevents accidental data dumps. It also makes reviews easier because the tool has a clear safe-by-default path.

Optional follow-up action (no writes)

On-call often needs to leave a trail for the next person. Instead of writing to the database, add an optional action that creates a ticket note payload or applies a tag in the incident system, but never touches customer records.

To keep access least privilege, the CLI should use a read-only log token, and a separate, scoped token for the ticket or tag action.

Store an audit record for every run: who executed it, which request ID, what time bounds were used, and whether they expanded details. That audit log is your safety net when something goes wrong or when access needs a review.

Common mistakes that create security and reliability issues

Small internal tools often start as “just a quick helper.” That’s exactly why they end up with risky defaults. The fastest way to lose trust is one bad incident, like a tool that deletes data when it was meant to be read-only.

The mistakes that show up most often:

- Giving the tool production database write access when it only needs reads, then assuming “we will be careful”

- Skipping an audit trail, so later you can’t answer who ran a command, what inputs they used, and what changed

- Allowing free-form SQL, regex, or ad hoc filters that accidentally scan huge tables or logs and take systems down

- Mixing environments so staging actions can reach production because configs, tokens, or base URLs are shared

- Printing secrets to a terminal, browser console, or logs, then forgetting those outputs get copied into tickets and chat

A realistic failure looks like this: an on-call engineer uses a log-search CLI during an incident. The tool accepts any regex and sends it to the log backend. One expensive pattern runs across hours of high-volume logs, spikes costs, and slows searches for everyone. In the same session, the CLI prints an API token in debug output, and it ends up pasted into a public incident doc.

Safer defaults that prevent most incidents

Treat read-only as a real security boundary, not a habit. Use separate credentials per environment, and separate service accounts per tool.

A few guardrails do most of the work:

- Use allow-listed queries (or templates) instead of raw SQL, and cap time ranges and row counts

- Log every action with a request ID, the user identity, the target environment, and the exact parameters

- Require explicit environment selection, with a loud confirmation for production

- Redact secrets by default, and disable debug output unless a privileged flag is used

If the tool can’t do something dangerous by design, your team won’t have to rely on perfect attention during a 3 a.m. incident.

Quick checklist before you ship the tool

Snapshot before changes

Capture a known-good state before you add risky actions or new data access.

Before your internal tool reaches real users (especially on-call), treat it like a production system. Confirm that access, permissions, and safety limits are real, not implied.

Start with access and permissions. Many accidents happen because “temporary” access becomes permanent, or because a tool quietly gains write power over time.

- Auth and offboarding: confirm who can sign in, how access is granted, and how it’s revoked the same day someone changes teams

- Roles stay small: keep 2-3 roles max (viewer, operator, admin) and write down what each role can do

- Read-only by default: make viewing the default path, and require an explicit role for anything that changes data

- Secrets handling: store tokens and keys outside the repo, and verify the tool never prints them in logs or error messages

- Break-glass flow: if you need emergency access, make it time-limited and logged

Then validate guardrails that prevent common mistakes:

- Confirmations for risky actions: require typed confirmations for deletes, backfills, or config changes

- Limits and timeouts: cap result size, enforce time windows, and time out queries so a bad request can’t run forever

- Input validation: validate IDs, dates, and environment names; reject anything that looks like “run everywhere”

- Audit logs: record who did what, when, and from where; make logs easy to search during incidents

- Basic metrics and errors: track success rate, latency, and top error types so you notice breakage early

Do change control like you would for any service: peer review, a few focused tests for the dangerous paths, and a rollback plan (including a way to disable the tool quickly if it misbehaves).

Next steps: roll out safely and keep improving

Treat the first release like a controlled experiment. Start with one team, one workflow, and a small set of real tasks. A log search tool for on-call is a solid pilot because you can measure time saved and spot risky queries quickly.

Keep the rollout predictable: pilot with 3 to 10 users, start in staging, gate access with least-privilege roles (not shared tokens), set clear usage limits, and record audit logs for every command or button click. Make sure you can roll back configuration and permissions changes quickly.

Write down the tool’s contract in plain language. List each command (or dashboard action), the allowed parameters, what success looks like, and what errors mean. People stop trusting internal tools when outputs feel ambiguous, even if the code is correct.

Add a feedback loop you actually check. Track which queries are slow, which filters are common, and which options confuse people. When you see repeated workarounds, that’s usually a sign the interface is missing a safe default.

Maintenance needs an owner and a schedule. Decide who updates dependencies, who rotates credentials, and who gets paged if the tool breaks during an incident. Review AI-generated changes like you would a production service: permission diffs, query safety, and logging.

If your team prefers chat-driven iteration, Koder.ai (koder.ai) can be a practical way to generate a small CLI or dashboard from a conversation, keep snapshots of known-good states, and roll back quickly when a change introduces risk.