Apr 12, 2025·8 min

Intuitive Surgical: Robotics Built for Recurring Revenue

See how Intuitive Surgical pairs surgical robots with training, services, and consumables to create recurring, procedure-based revenue beyond one-time hardware sales.

See how Intuitive Surgical pairs surgical robots with training, services, and consumables to create recurring, procedure-based revenue beyond one-time hardware sales.

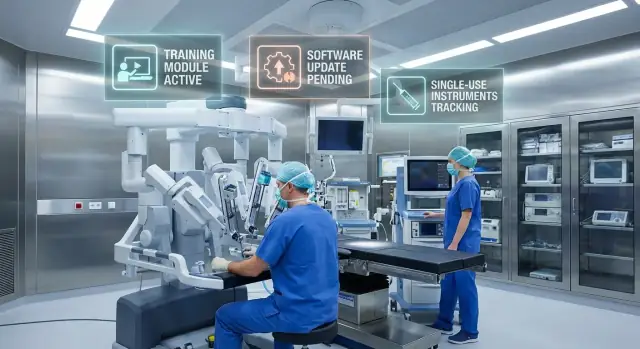

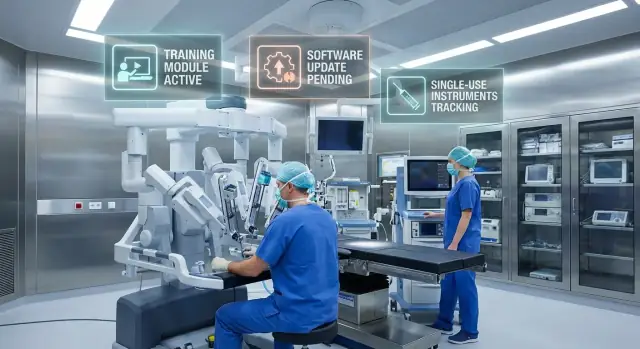

Surgical robots are often described as “hardware + ecosystem.” In plain terms, the robot is the headline product, but the ongoing value (and spending) sits in everything around it: specialized instruments, procedure-specific supplies, software updates, training, and service.

That’s why surgical robotics is more than a one-time device sale. A hospital doesn’t buy a robot like it buys a standard piece of equipment and then forgets about it. Once a team starts performing procedures on a platform like the da Vinci system, each case tends to require compatible instruments and consumables. Those items are replenished continually, so revenue can track procedure volume rather than just new unit sales.

This article looks at business-model mechanics—how companies such as Intuitive Surgical can generate procedure-driven revenue and build a healthcare platform strategy. It is not medical advice, and it doesn’t judge clinical outcomes.

A simplified way to think about recurring revenue in surgical robotics is three layers that reinforce each other:

Robotics: a high-cost platform that becomes part of a hospital’s surgical program.

Training: structured education for surgeons and care teams that reduces adoption friction and helps standardize how the system is used.

Consumables and instruments: the repeat-purchase layer that can make each procedure feel like a subscription in practice, even though it’s billed per case.

Put together, the model can resemble a recurring business: a large upfront installation followed by steady, workflow-linked demand over time.

The starting point of Intuitive Surgical’s model is a capital platform: the da Vinci system. It’s expensive, durable, and planned for like other major hospital assets—think multi-year budgeting, committee approvals, and careful forecasting.

A surgical robot isn’t a “replace every year” device. Hospitals expect a long useful life, which shifts the conversation away from quick payback and toward sustained value: reliability, surgeon adoption, and consistent case volume over many years.

Because these purchases are large, they often move through formal capital planning cycles. That naturally slows down new placements—but it also makes each placement strategically meaningful once it happens.

Placement is the strategic win. Once a robot is installed, the hospital has an on-site capability it wants to use. That creates a gravity effect: surgeons schedule cases where the system is available, administrators want utilization to justify the investment, and service teams build routines around keeping the platform running.

In other words, the installed base is the “anchor” that enables everything else: procedure volume, instrument pull-through, training demand, and service agreements.

The robot itself is typically a capital purchase (or capital-like financing). But day-to-day activity surrounding it shifts spending into operating budgets: disposable items, procedure-specific instruments, maintenance, and software-related services.

This split matters. Even if capital spending is cyclical, operating budgets can be steadier—especially when the system is already integrated into the surgical schedule.

Owning the platform doesn’t create recurring revenue by itself—using it does. Higher procedure volume increases ongoing purchases tied to each case, making utilization the bridge between a one-time platform sale and repeat demand.

For surgical robotics, the big, headline-grabbing sale is the robot. The quieter engine underneath is consumables—items used during an operation that must be replaced regularly.

In this context, consumables typically include:

These products aren’t “nice-to-haves.” They’re essential to completing a procedure safely and consistently.

Every additional procedure performed on a system increases demand for instruments and accessories. Some tools are designed with use limits (for example, a set number of procedures) and then must be replaced. That structure naturally ties revenue to clinical activity: more cases performed → more consumables required.

This mechanism also makes the business less dependent on the timing of large capital purchases. Hardware sales can be episodic—hospitals buy when budgets, approvals, and capacity line up. Consumables, by contrast, can track the steadier rhythm of patient demand.

Healthcare has strong reasons to favor single-use or limited-use items:

These clinical realities can justify ongoing replacement without needing aggressive sales tactics.

It’s tempting to jump to exact pricing, margins, or contract terms. Those details vary by hospital, region, and agreement structure—and they change over time. The durable takeaway is the mechanism: a platform that drives procedure-linked replenishment, turning utilization into repeat demand.

A surgical robot is only as useful as the team’s ability to use it safely and consistently. That makes training more than a “nice to have”—it’s a core adoption lever. When a hospital can ramp up surgeons, nurses, and OR staff with predictable steps, the robot shifts from a risky capital purchase to a dependable clinical capability.

Most programs follow a familiar progression: initial onboarding (system basics and safety), simulation or dry-lab practice, supervised cases with proctoring, and then continuing education to refine technique and incorporate new procedures.

That structure matters for two reasons:

Training often plugs directly into hospital credentialing—formal requirements for who can perform which procedures. Once a hospital builds a standardized pathway (checklists, minimum case counts, proctor sign-off), it becomes easier to scale the program to additional surgeons.

Standardization also affects the broader OR workflow. As teams repeat the same setup, docking, instrument handling, and troubleshooting routines, procedure time and error rates can improve. That consistency supports surgeon confidence and helps administrators justify continued use.

As surgeons gain proficiency, they may feel comfortable taking on a wider range of cases. Over time, that can increase the addressable pool of procedures for the platform.

This creates loyalty, but it’s not absolute exclusivity. Hospitals can and do evaluate alternatives. Training works more like a practical moat: it reduces friction, builds internal champions, and makes the “default choice” easier—especially when paired with good outcomes and reliable support.

Once a surgical robot becomes part of an OR schedule, the expectation shifts to “this must work every day.” That’s why service and support can be as strategic as the hardware itself: reliability protects procedure volume, and procedure volume is what keeps the whole economics moving.

Operating rooms run on tight calendars, staffed teams, and pre-op/post-op coordination. If a system is down unexpectedly, it doesn’t just delay a case—it can trigger a chain reaction: rescheduling surgeons, rebooking anesthesia teams, and shifting patients (sometimes to other facilities). Strong service performance reduces that disruption, making the platform easier for hospital administrators to commit to.

Service revenue often gets summarized as “maintenance contracts,” but the operational reality is broader:

Even without getting into proprietary details, the principle is simple: the closer service is to the hospital’s workflow, the more valuable it becomes.

Support quality shapes clinician confidence. When teams believe the system will be available—and that help will be competent and quick when something goes wrong—they’re more willing to schedule high-value cases on it, train additional staff, and standardize around the platform.

That turns service into a retention lever: it protects the installed base, reduces reasons to trial alternatives, and quietly supports expansion to more rooms, more sites, and more procedures.

A surgical robot may be the headline purchase, but software is where the experience can keep improving after installation. Hospitals don’t just buy a machine—they buy an evolving operating workflow that can be refined through updates, new features, and better coordination across teams.

Modern surgical platforms rely on software for visualization, user interfaces, safety checks, and system performance. Periodic upgrades can add features that matter to everyday users: smoother setup steps, clearer on-screen guidance, improved troubleshooting, and tools that help standardize how procedures are performed.

This creates a clear “why stay current?” incentive. When hospitals see measurable benefits—shorter room turnover, fewer setup errors, more consistent technique—they’re more willing to pay for upgrade paths, optional modules, or recurring software-related services.

Even without getting technical, the value of data is easy to grasp: it turns operating room activity into something that can be reviewed, compared, and improved.

Examples of what software and data tools can support:

The common thread is operational learning: small improvements repeated across many cases can add up to meaningful capacity and cost impact.

Connectivity increases value, but it also raises expectations. Hospitals need clear answers on security updates, access control, audit logs, and how patient-related information is handled. Regular patches, documented security practices, and compliance-aligned processes become part of the product—not an afterthought—especially as health systems tighten vendor requirements.

For health systems with multiple hospitals, software can act like a playbook: consistent settings, consistent reporting, consistent training aids, and consistent workflows. That standardization reduces variation, helps leadership compare performance fairly, and makes it easier to move staff between sites—further strengthening commitment to the platform.

Surgical robots aren’t “sticky” just because they’re expensive. They become hard to replace because they reshape how people work—surgeons, nurses, sterile processing, anesthesia, and scheduling all adapt around the platform. Once that change is absorbed, reverting (or switching to a different system) can feel like reopening a project the hospital already paid for in time, attention, and political capital.

For surgeons, switching isn’t like changing a smartphone. It can mean re-learning hand-eye coordination, console controls, and procedural flow—often while trying to maintain outcomes and speed. For the OR team, there’s new setup, draping, docking routines, and troubleshooting habits. Even if another system is “comparable,” the training time and the confidence curve are real costs.

Robotic programs affect OR scheduling (block time, turnover), staffing (trained scrub techs and bedside assistants), and process design (where the robot is stored, how it’s moved, how instruments are picked). Once a hospital optimizes these workflows, switching platforms can temporarily slow throughput—an operational penalty that rarely shows up on a purchase order.

Recurring-use instruments and accessories encourage standardization: stocking, sterilization cycles, tray configurations, and vendor coordination. Over time, hospitals build a “known-good” operating model around the ecosystem, making alternatives feel risky—even if cheaper on paper.

When people say a robot is “integrated,” they usually mean the OR can run smoothly: trained staff are available, preference cards are tuned, supplies arrive on time, and leadership has a clear playbook. That practical integration creates switching costs that can be stronger than any software interface.

Hospitals don’t buy a surgical robot because it’s impressive—they buy it because the math can work. The challenge is that the economics are rarely “one-size-fits-all.” A da Vinci program can look attractive in one service line and questionable in another, even inside the same hospital.

A robot has a large upfront price, but the day-to-day decision is operational: can we run enough appropriate cases to justify ongoing instrument, consumable, and service costs?

Key variables include:

Robotic assistance often doesn’t automatically mean higher reimbursement. Payment depends on procedure codes, payer mix, and local rules, so the “ROI story” can flip between regions. That’s why hospitals typically model economics per procedure family (e.g., urology vs. gynecology) rather than treating robotics as a single bucket.

Most business cases quietly hinge on utilization. If the robot sits idle, fixed costs dominate. Hospitals therefore set targets (cases per week, block time, surgeon adoption) and may delay additional systems until utilization is consistently high.

Surgeons can be the internal champions who make volume real—training, preference, and confidence matter. Patient demand can amplify this, but it can also create pressure: marketing may raise expectations beyond what outcomes data supports.

When you see ROI or outcomes claims, ask:

Careful economics is less about a single headline metric and more about operational discipline over time.

Surgical robots don’t sell like ordinary capital equipment. Hospitals can’t just pick a unit from a catalog and “try it out.” Regulation, clinical evidence, and formal purchasing processes act as high-friction gates—and those gates shape who wins and how recurring revenue gets protected.

Before a system (and often specific instruments, software features, or procedure claims) can be marketed, it must meet stringent safety and performance expectations from regulators. That typically means documented design controls, risk management, validation testing, and clinical or real-world evidence appropriate to the claim.

For buyers, this matters because the “approved use” boundaries influence what procedures the robot can support today—and what extensions might realistically arrive later. Vendors with a track record of navigating approvals tend to be seen as lower execution risk.

Healthcare is unusually documentation-heavy for good reasons: patient safety, auditability, and liability.

Hospitals care about questions like:

A mature training and documentation stack reduces internal friction: it helps credentialing, standardizes workflows, and makes it easier for the hospital to defend its practices in audits or adverse-event reviews. These “paperwork” capabilities can become a quiet differentiator.

Large purchases often run through value analysis committees, perioperative leadership, biomedical engineering, IT/security reviews, and sometimes payer-facing discussions. Many hospitals also want demos, site visits, or limited trials, followed by multi-year contracting.

That complexity creates inertia: once a platform is selected, hospitals prefer to expand within that ecosystem rather than restart months of evaluation for a new one.

When compliance requirements are strict, proven systems with established service processes, upgrade pathways, and training programs can look “safer” to decision-makers. The result is a barrier that protects incumbents: not because competitors can’t build a robot, but because matching the total regulated operating environment takes years—and buyers feel the difference.

Recurring revenue in surgical robotics is powerful, but it’s not automatic. The same levers that create repeat demand—installed base, procedure-linked consumables, service contracts, and training—also create clear failure points.

New surgical robotics firms can attack the model from the edges: lower upfront platform prices, narrower specialty focus, or pricing bundles that undercut per-procedure instrument spend. Adjacent technologies (advanced laparoscopy tools, imaging, navigation, or AI-driven workflow support) can also reduce the perceived need for a premium robot in certain cases.

Hospitals may accept a high capital purchase but push hard on ongoing costs once the system is installed. If procurement teams standardize instruments across sites, demand volume discounts, or limit instrument usage per case, the procedure-driven revenue engine slows. Service contracts face similar scrutiny: buyers want predictable uptime, but will challenge renewals if performance doesn’t clearly justify the price.

If growth is concentrated in a few specialties, shifts in clinical guidelines, reimbursement, or surgeon preferences can ripple through utilization. A robot that’s busy in urology but underused elsewhere can leave hospitals questioning expansion plans.

A breakthrough modality—new energy devices, non-robotic minimally invasive techniques, or automation that shortens OR time—could change what hospitals value, making the current instrument and training model less compelling.

Recurring revenue depends on reliable logistics and field support. Instrument shortages, delays in reprocessing cycles, or thin service coverage can directly reduce procedures, hurting both revenue and trust.

You don’t need to build surgical robots to learn from Intuitive Surgical. The repeatable value isn’t created by “a device.” It’s created by a system that makes every successful use easier, safer, and more predictable than the last.

Recurring revenue works best when customers can point to a simple, defensible “unit” that grows with outcomes: a procedure, a test, a scan, a shipment, a completed job.

Design your offering so each unit naturally consumes something: time-saving tools, replenishable components, per-use services, or measurable workflow support. If repeat usage is optional or vague, your revenue will be too.

Training isn’t just education—it’s adoption insurance.

Create a loop that keeps users improving: structured training paths, certification, peer community, best-practice playbooks, and refreshers when features change. The goal is to reduce “fear of doing it wrong,” which is a hidden churn driver in high-tech products.

A strong enablement loop also creates internal champions who defend the purchase when budgets tighten.

Customers don’t pay recurring fees because they love contracts. They pay because downtime is expensive, stressful, and visible.

Treat service, support, and maintenance as part of the product promise. Make uptime predictable, response times clear, and replacements straightforward. When reliability is designed in—and backed by accountable support—renewals feel like risk reduction rather than extra spend.

Software earns its keep when it removes steps, standardizes work, and helps teams coordinate—not when it only adds dashboards.

Look for workflow moments where users lose time: setup, documentation, handoffs, training, compliance, and reporting. If software reduces friction in those areas, it becomes sticky in a way hardware alone rarely can.

A useful parallel from outside medtech is vibe-coding platforms like Koder.ai: teams “install” a development environment once, then recurring value comes from repeated usage—generating and iterating on web apps (React), backends (Go + PostgreSQL), or mobile apps (Flutter) through a chat interface. The platform’s sticky layer is not just feature count, but workflow reliability (deployments/hosting, custom domains, snapshots and rollback) and enablement (planning mode and guided iteration), which mirrors the same adoption mechanics described above.

If you want a broader primer on recurring business mechanics beyond medtech, see /blog/recurring-revenue-models.

Recurring revenue in medtech often comes from usage, not monthly plans. A hospital buys (or finances) a capital system, then each procedure triggers ongoing demand for instruments, accessories, sterile drapes, and other single-use items. On top of that, service agreements and software upgrades can create predictable annual revenue even when there’s no “subscription” label.

The key is that revenue scales with procedure volume: more cases typically means more consumables, more maintenance, and more training activity.

Consumables are most defensible when they’re tightly coupled to safety, performance, and regulatory requirements—think items that must meet validated specs, integrate seamlessly with the platform, and support consistent outcomes. Design choices (compatibility, instrument tracking, limited re-use cycles) can also protect quality and reduce variability.

What’s less defensible: generic items with many equivalent suppliers, or products where hospitals can safely standardize alternatives without changing workflows.

Usually both, but the strategic value is often bigger than the direct revenue. Training reduces hesitation, shortens the time to proficiency, and helps sites expand to more surgeons and procedures. It also creates a shared “way of working” that makes the platform easier to adopt across a department.

Even when training is billed, it’s frequently priced to remove friction rather than maximize margin.

Ask for assumptions, not just outcomes. Separate (1) clinical goals, (2) operational impact (OR time, turnover, staffing), and (3) financial effects (length of stay, complications, throughput). Insist on site-specific modeling: case mix, realistic utilization ramp, and the full cost stack—capital, service, consumables, and training.

A helpful approach is a sensitivity check: “What happens if procedure volume is 20% lower than forecast?”

A surgical robotics company can earn recurring revenue through usage-driven spending rather than monthly subscriptions:

The common mechanism is that revenue scales with procedure volume, not just new robot placements.

Instruments and consumables are most defensible when they’re clinically and operationally coupled to the platform:

They’re least defensible when they’re and hospitals can safely substitute alternatives without disrupting workflow.

Utilization is the bridge between a one-time platform sale and ongoing demand. If the robot is used more often:

A robot sitting idle can’t create meaningful recurring revenue, even if the installed base is large.

Placement creates an installed base anchor inside the hospital:

Once the platform becomes part of daily operations, it naturally pulls through instruments, consumables, service, and training—without needing another capital purchase right away.

Hospitals often split spending into:

This matters because capital budgets can be cyclical, while operating spend can be steadier once the system is embedded in the surgical schedule.

Training primarily reduces adoption risk and accelerates ramp-up:

Even when training is paid, many vendors treat it as a growth lever: faster proficiency → more cases → more procedure-linked demand.

Service supports the operational promise of “this system will be available when scheduled.” Strong service typically includes:

Because downtime directly reduces procedures, service quality can protect both hospital satisfaction and recurring revenue.

Software extends value after installation by improving workflow rather than just adding features:

When updates measurably reduce friction (turnover, readiness, documentation), hospitals have a stronger reason to stay current.

Switching costs are often practical and operational:

Even if an alternative is cheaper on paper, the temporary disruption and retraining burden can make switching unattractive.

A practical ROI check focuses on assumptions and site specifics:

When reviewing broad ROI claims, always ask “compared to what?” (open, laparoscopy, another robot) and whether assumptions match your setting.