Dec 15, 2025·8 min

James Gosling, Java, and the Rise of “Write Once, Run Anywhere”

How James Gosling’s Java and “Write Once, Run Anywhere” influenced enterprise systems, tooling, and today’s backend practices—from JVM to cloud.

What This Post Covers (and Why It Still Matters)

Java’s most famous promise—“Write Once, Run Anywhere” (WORA)—wasn’t marketing fluff for backend teams. It was a practical bet: you could build a serious system once, deploy it across different operating systems and hardware, and keep it maintainable as the company grew.

This post explains how that bet worked, why enterprises adopted Java so quickly, and how decisions made in the 1990s still shape modern backend development—frameworks, build tools, deployment patterns, and the long-lived production systems many teams still operate.

What you’ll get from this history

We’ll start with James Gosling’s original goals for Java and how the language and runtime were designed to reduce portability headaches without sacrificing performance too badly.

Then we’ll follow the enterprise story: why Java became a safe choice for big organizations, how app servers and enterprise standards emerged, and why tooling (IDEs, build automation, testing) became a force multiplier.

Finally, we’ll connect the “classic” Java world to current realities—Spring’s rise, cloud deployments, containers, Kubernetes, and what “run anywhere” really means when your runtime includes dozens of services and third-party dependencies.

Key terms (used throughout the post)

Portability: The ability to run the same program across different environments (Windows/Linux/macOS, different CPU types) with minimal or no changes.

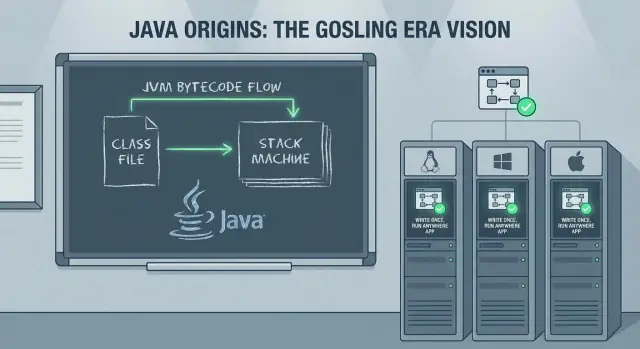

JVM (Java Virtual Machine): The runtime that executes Java programs. Instead of compiling directly to machine-specific code, Java targets the JVM.

Bytecode: The intermediate format produced by the Java compiler. Bytecode is what the JVM runs, and it’s the core mechanism behind WORA.

WORA still matters because many backend teams are balancing the same trade-offs today: stable runtimes, predictable deployments, team productivity, and systems that need to survive for a decade or more.

James Gosling and the Original Goals of Java

Java is closely associated with James Gosling, but it was never a solo effort. At Sun Microsystems in the early 1990s, Gosling worked with a small team (often referred to as the “Green” project) aiming to build a language and runtime that could move across different devices and operating systems without being rewritten each time.

The result wasn’t just a new syntax—it was a full “platform” idea: a language, a compiler, and a virtual machine designed together so software could be shipped with fewer surprises.

The goals: safety, portability, productivity

A few practical goals shaped Java from day one:

- Safety and reliability: Java removed or constrained common sources of crashes seen in C/C++—notably direct pointer manipulation—and added runtime checks that favored predictable failures over silent corruption.

- Portability: Instead of compiling to a CPU’s machine code, Java compiles to bytecode that can run on a compatible JVM. That decision made “cross-platform” less about conditional compilation and more about a consistent runtime contract.

- Developer productivity: Java aimed to make everyday programming faster and less error-prone through a standard library, consistent tooling expectations, and automatic memory management.

These weren’t academic goals. They were responses to real costs: debugging memory issues, maintaining multiple platform-specific builds, and onboarding teams onto complex codebases.

What “Write Once, Run Anywhere” meant (and didn’t)

In practice, WORA meant:

- If you target the JVM, you can usually ship the same bytecode to different operating systems.

- You still need to manage environment differences: file paths, locale behavior, networking quirks, performance characteristics, native integrations, and deployment packaging.

So the slogan wasn’t “magical portability.” It was a shift in where portability work happens: away from per-platform rewrites and toward a standardized runtime and libraries.

How WORA Works: Bytecode and the JVM

WORA is a compilation and runtime model that splits building software from running it.

Source code → bytecode → JVM execution

Java source files (.java) are compiled by javac into bytecode (.class files). Bytecode is a compact, standardized instruction set that’s the same whether you compiled on Windows, Linux, or macOS.

At runtime, the JVM loads that bytecode, verifies it, and executes it. Execution can be interpreted, compiled on the fly, or a mix of both depending on the JVM and workload.

The JVM as an OS/CPU “adapter”

Instead of generating machine code for every target CPU and operating system at build time, Java targets the JVM. Each platform provides its own JVM implementation that knows how to:

- translate bytecode into native instructions for the local CPU

- interact with the local operating system (files, networking, threads)

That abstraction is the core trade: your application talks to a consistent runtime, and the runtime talks to the machine.

Runtime checks and memory management

Portability also depends on guarantees enforced at runtime. The JVM performs bytecode verification and other checks that help prevent unsafe operations.

And rather than requiring developers to manually allocate and free memory, the JVM provides automatic memory management (garbage collection), reducing a whole category of platform-specific crashes and “works on my machine” bugs.

Why this simplified deployment across fleets

For enterprises running mixed hardware and operating systems, the payoff was operational: ship the same artifacts (JARs/WARs) to different servers, standardize on a JVM version, and expect broadly consistent behavior. WORA didn’t eliminate all portability issues, but it narrowed them—making large-scale deployments easier to automate and maintain.

Why Enterprises Adopted Java So Quickly

Enterprises in the late 1990s and early 2000s had a very specific wish list: systems that could run for years, survive staff turnover, and be deployed across a messy mix of UNIX boxes, Windows servers, and whatever hardware procurement had negotiated that quarter.

Java arrived with an unusually enterprise-friendly story: teams could build once and expect consistent behavior across heterogeneous environments, without maintaining separate codebases per operating system.

Fewer rewrites, less QA churn

Before Java, moving an application between platforms often meant rewriting platform-specific portions (threads, networking, file paths, UI toolkits, and compiler differences). Every rewrite multiplied testing effort—and enterprise testing is expensive because it includes regression suites, compliance checks, and “it must not break payroll” caution.

Java reduced that churn. Instead of validating multiple native builds, many organizations could standardize on a single build artifact and a consistent runtime, lowering ongoing QA costs and making long lifecycle planning more realistic.

A standard library that behaved the same

Portability isn’t only about running the same code; it’s also about relying on the same behavior. Java’s standard libraries offered a consistent baseline for core needs like:

- Networking and web protocols

- Database connectivity (via JDBC and vendor drivers)

- Security primitives

- Threading and concurrency building blocks

This consistency made it easier to form shared practices across teams, onboard developers, and adopt third-party libraries with fewer surprises.

Where portability still broke

The “write once” story wasn’t perfect. Portability could fall apart when teams depended on:

- Native libraries (JNI) for hardware integration or legacy code

- OS-specific file system quirks, fonts, or locale behavior

- Vendor-specific database or application server features

Even so, Java often narrowed the problem to a small, well-defined edge—rather than making the whole application platform-specific.

Enterprise Platforms: App Servers and Jakarta EE

As Java moved from desktops into corporate data centers, teams needed more than a language and a JVM—they needed a predictable way to deploy and operate shared backend capabilities. That demand helped fuel the rise of application servers such as WebLogic, WebSphere, and JBoss (and, at the lighter end, servlet containers like Tomcat).

Standardized deployment (WAR/EAR)

One reason app servers spread quickly was the promise of standardized packaging and deployment. Instead of shipping a custom install script for every environment, teams could bundle an application as a WAR (web archive) or EAR (enterprise archive) and deploy it into a server with a consistent runtime model.

That model mattered to enterprises because it separated concerns: developers focused on business code, while operations relied on the app server for configuration, security integration, and lifecycle management.

Enterprise patterns everyone needed

App servers popularized a set of patterns that show up in almost every serious business system:

- Transactions: coordinating multi-step operations (often across databases and services) so failures don’t leave data half-written.

- Messaging: asynchronous work via queues and topics, smoothing traffic spikes and decoupling systems.

- Connection pooling: reusing expensive database connections rather than opening one per request.

These weren’t “nice-to-haves”—they were the plumbing required for reliable payment flows, order processing, inventory updates, and internal workflows.

From servlets/JSP to modern web backends

The servlet/JSP era was an important bridge. Servlets established a standard request/response model, while JSP made server-side HTML generation approachable.

Even though the industry later shifted toward APIs and front-end frameworks, servlets laid groundwork for today’s web backends: routing, filters, sessions, and consistent deployment.

Jakarta EE as a standardization effort

Over time, these capabilities were formalized as J2EE, later Java EE, and now Jakarta EE: a collection of specifications for enterprise Java APIs. Jakarta EE’s value is in standardizing interfaces and behavior across implementations, so teams can build against known contracts rather than a single vendor’s proprietary stack.

Performance: JIT, GC, and the Cost of Portability

Go from idea to app

Turn an idea into a working web backend without setting up a full project first.

Java’s portability raised an obvious question: if the same program can run on very different machines, how can it also be fast? The answer is a set of runtime technologies that made portability practical for real workloads—especially on servers.

Garbage Collection: less time managing memory, fewer production bugs

Garbage collection (GC) mattered because large server applications create and discard huge numbers of objects: requests, sessions, cached data, parsed payloads, and more. In languages where teams manually manage memory, these patterns often lead to leaks, crashes, or hard-to-debug corruption.

With GC, teams could focus on business logic rather than “who frees what, and when.” For many enterprises, that reliability advantage outweighed micro-optimizations.

JIT compilation: the performance bridge for portability

Java runs bytecode on the JVM, and the JVM uses Just-In-Time (JIT) compilation to translate hot parts of your program into optimized machine code for the current CPU.

That’s the bridge: your code stays portable, while the runtime adapts to the environment it’s actually running in—often improving performance over time as it learns which methods are used most.

The tradeoffs: warm-up, tuning, and latency sensitivity

These runtime smarts aren’t free. JIT introduces warm-up time, where performance can be slower until the JVM has observed enough traffic to optimize.

GC can also introduce pauses. Modern collectors reduce them dramatically, but latency-sensitive systems still need careful choices and tuning (heap sizing, collector selection, allocation patterns).

Profiling as a normal part of Java work

Because so much performance depends on runtime behavior, profiling became routine. Java teams commonly measure CPU, allocation rates, and GC activity to find bottlenecks—treating the JVM as something you observe and tune, not a black box.

Tooling That Changed Team Productivity

Java didn’t win teams over on portability alone. It also shipped with a tooling story that made large codebases survivable—and made “enterprise-scale” development feel less like guesswork.

IDEs: from editing files to understanding systems

Modern Java IDEs (and the language features they leaned on) changed daily work: accurate navigation across packages, safe refactoring, and always-on static analysis.

Rename a method, extract an interface, or move a class between modules—then have imports, call sites, and tests update automatically. For teams, that meant fewer “don’t touch that” areas, faster code reviews, and more consistent structure as projects grew.

Builds and dependencies: Ant → Maven/Gradle

Early Java builds often relied on Ant: flexible, but easy to turn into a custom script that only one person understood. Maven pushed a convention-based approach with a standard project layout and a dependency model that could be reproduced on any machine. Gradle later brought more expressive builds and faster iteration while keeping dependency management front-and-center.

The big shift was repeatability: the same command, the same result, across developer laptops and CI.

Why standard tooling helped teams scale

Standard project structures, dependency coordinates, and predictable build steps reduced tribal knowledge. Onboarding got easier, releases became less manual, and it became practical to enforce shared quality rules (formatting, checks, test gates) across many services.

Practical checklist for a modern Java project

- Use a current LTS JDK (and pin it in CI).

- Pick Maven or Gradle; keep the build minimal and documented.

- Centralize dependency versions (BOM or version catalog).

- Add formatting + static checks (e.g., Checkstyle/SpotBugs) as build steps.

- Require unit tests and generate coverage reports.

- Use a reproducible CI pipeline that runs build + tests on every change.

- Document “how to run locally” in a short README.

Testing and Delivery: From JUnit to CI/CD

Test an API idea

Stand up a web server app quickly for proofs of concept and integration tests.

Java teams didn’t just get a portable runtime—they got a culture shift: testing and delivery became something you could standardize, automate, and repeat.

How JUnit made unit tests “normal”

Before JUnit, tests were often ad-hoc (or manual) and lived outside the main development loop. JUnit changed that by making tests feel like first-class code: write a small test class, run it in your IDE, and get immediate feedback.

That tight loop mattered for enterprise systems where regressions are expensive. Over time, “no tests” stopped being a quirky exception and started looking like risk.

CI benefits: one build, many environments

A big advantage of Java delivery is that builds are typically driven by the same commands everywhere—developer laptops, build agents, Linux servers, Windows runners—because the JVM and build tools behave consistently.

In practice, that consistency reduced the classic “works on my machine” problem. If your CI server can run mvn test or gradle test, most of the time you get the same results the whole team sees.

Code quality tooling that fits into the pipeline

Java ecosystems made “quality gates” straightforward to automate:

- Formatting: Spotless or a shared IDE formatter config to keep diffs clean

- Linting/static analysis: Checkstyle, PMD, SpotBugs for common mistakes

- Security scans: OWASP Dependency-Check (or a hosted tool like Snyk) to flag vulnerable libraries

These tools work best when they’re predictable: same rules for every repo, enforced in CI, with clear failure messages.

A simple CI pipeline for a Java service

Keep it boring and repeatable:

- Checkout + set Java version (pin your JDK)

- Build + unit tests (

mvn test/gradle test) - Static checks (format, lint, security scan)

- Package artifact (JAR) and store it

- Integration tests (optional, but valuable)

- Deploy to staging, then production with approvals

That structure scales from one service to many—and it echoes the same theme: a consistent runtime and consistent steps make teams faster.

Spring and the Shift to Modern Backend Development

Java earned trust in enterprises early, but building real business applications often meant wrestling with heavy app servers, verbose XML, and container-specific conventions. Spring changed the day-to-day experience by making “plain” Java the center of backend development.

Inversion of Control: why it fit enterprise needs

Spring popularized inversion of control (IoC): instead of your code creating and wiring everything manually, the framework assembles the application from reusable components.

With dependency injection (DI), classes declare what they need, and Spring provides it. This improves testability and makes it easier for teams to swap implementations (for example, a real payment gateway vs. a stub in tests) without rewriting business logic.

Simplified configuration and integration

Spring reduced friction by standardizing common integrations: JDBC templates, later ORM support, declarative transactions, scheduling, and security. Configuration moved from long, brittle XML toward annotations and externalized properties.

That shift also aligned well with modern delivery: the same build can run locally, in staging, or in production by changing environment-specific config rather than code.

WORA, portability, and modern service patterns

Spring-based services kept the “run anywhere” promise practical: a REST API built with Spring can run unchanged on a developer laptop, a VM, or a container—because the bytecode targets the JVM, and the framework abstracts many platform details.

Today’s common patterns—REST endpoints, dependency injection, and configuration via properties/env vars—are essentially Spring’s default mental model for backend development. For more on deployment realities, see /blog/java-in-the-cloud-containers-kubernetes-and-reality.

Java in the Cloud: Containers, Kubernetes, and Reality

Java didn’t need a “cloud rewrite” to run in containers. A typical Java service is still packaged as a JAR (or WAR), launched with java -jar, and placed into a container image. Kubernetes then schedules that container like any other process: start it, watch it, restart it, and scale it.

What changes in containers (even if your code doesn’t)

The big shift is the environment around the JVM. Containers introduce stricter resource boundaries and faster lifecycle events than traditional servers.

Memory limits are the first practical gotcha. In Kubernetes, you set a memory limit, and the JVM must respect it—or the pod gets killed. Modern JVMs are container-aware, but teams still tune heap sizing to leave room for metaspace, threads, and native memory. A “works on VM” service can still crash in a container if the heap is sized too aggressively.

Startup time matters more too. Orchestrators scale up and down frequently, and slow cold starts can affect autoscaling, rollouts, and incident recovery. Image size becomes operational friction: bigger images pull slower, extend deploy times, and waste registry/network bandwidth.

Making Java fit better: smaller, faster, more predictable

Several approaches helped Java feel more natural in cloud deployments:

- Lighter runtimes: slim base images and trimming the runtime with tools like

jlink(when practical) reduces image size. - Faster startup: class data sharing (CDS) and careful dependency hygiene can reduce cold-start overhead.

- Alternative packaging: ahead-of-time compilation (for suitable services) can dramatically improve startup and memory profiles, at the cost of different build/debug trade-offs.

For a practical walkthrough of tuning JVM behavior and understanding performance trade-offs, see /blog/java-performance-basics.

Backwards Compatibility and Long-Lived Systems

Iterate safely

Capture snapshots and roll back changes when experiments don’t pan out.

One reason Java earned trust in enterprises is simple: code tends to outlive teams, vendors, and even business strategies. Java’s culture of stable APIs and backwards compatibility meant that an application written years ago could often keep running after OS upgrades, hardware refreshes, and new Java releases—without a total rewrite.

Why stable APIs matter in enterprises

Enterprises optimize for predictability. When core APIs stay compatible, the cost of change drops: training materials stay relevant, operational runbooks don’t need constant rewrites, and critical systems can be improved in small steps instead of big-bang migrations.

That stability also shaped architecture choices. Teams were comfortable building large shared platforms and internal libraries because they expected them to keep working for a long time.

Libraries, maintenance, and the “forever” expectation

Java’s library ecosystem (from logging to database access to web frameworks) reinforced the idea that dependencies are long-term commitments. The flip side is maintenance: long-lived systems accumulate old versions, transitive dependencies, and “temporary” workarounds that become permanent.

Security updates and dependency hygiene are ongoing work, not a one-time project. Regularly patching the JDK, updating libraries, and tracking CVEs reduces risk without destabilizing production—especially when upgrades are incremental.

Upgrading older Java apps safely

A practical approach is to treat upgrades like product work:

- Start by adding or improving automated tests around critical workflows.

- Upgrade in small jumps (e.g., one LTS line at a time) and measure performance and memory, not just compilation.

- Run old and new versions side-by-side in staging, and keep rollback plans explicit.

- Inventory dependencies early; many “Java upgrades” fail because a key library is abandoned.

Backwards compatibility isn’t a guarantee that everything will be painless—but it’s a foundation that makes careful, low-risk modernization possible.

Key Lessons for Backend Teams Today

What WORA actually delivered (and what it didn’t)

WORA worked best at the level Java promised: the same compiled bytecode could run on any platform with a compatible JVM. That made cross-platform server deployments and vendor-neutral packaging far easier than in many native ecosystems.

Where it fell short was everything around the JVM boundary. Differences in operating systems, filesystems, networking defaults, CPU architectures, JVM flags, and third‑party native dependencies still mattered. And performance portability was never automatic—you could run anywhere, but you still had to observe and tune how it ran.

Practical takeaways for teams choosing Java today

Java’s biggest advantage isn’t a single feature; it’s the combination of stable runtimes, mature tooling, and a huge hiring pool.

A few team-level lessons worth carrying forward:

- Treat the JVM as a platform: pick a supported JDK distribution, standardize versions, and upgrade deliberately.

- Prefer boring defaults: keep builds, logging, metrics, and dependency management consistent across services.

- Design for operability: invest early in monitoring, safe configuration, and predictable memory/GC behavior.

- Lean on the ecosystem: frameworks and libraries save time, but audit dependency sprawl and security updates.

Decision factors: when Java is the right call

Choose Java when your team values long-term maintenance, strong library support, and predictable production operations.

Check these decision factors:

- Team skills: Do you already have Java/Spring experience, or will you be training from scratch?

- Runtime constraints: Are startup time and memory footprint critical (some workloads favor Go/Node), or is throughput and stability the priority?

- Ecosystem needs: Do you need mature messaging, database drivers, observability, or enterprise integrations?

- Longevity: Will this system live for years with minimal rewrites?

Next steps

If you’re evaluating Java for a new backend or modernization effort, start with a small pilot service, define an upgrade/patching policy, and agree on a framework baseline. If you want help scoping those choices, reach out via /contact.

If you’re also experimenting with faster ways to stand up “sidecar” services or internal tools around an existing Java estate, platforms like Koder.ai can help you go from an idea to a working web/server/mobile app through chat—useful for prototyping companion services, dashboards, or migration utilities. Koder.ai supports code export, deployment/hosting, custom domains, and snapshots/rollback, which pairs well with the same operational mindset Java teams value: repeatable builds, predictable environments, and safe iteration.