Oct 26, 2025·8 min

JavaScript vs TypeScript: Differences, Pros, and Use Cases

Compare JavaScript and TypeScript with clear examples: typing, tooling, speed, maintainability, and when each fits. Includes practical migration tips.

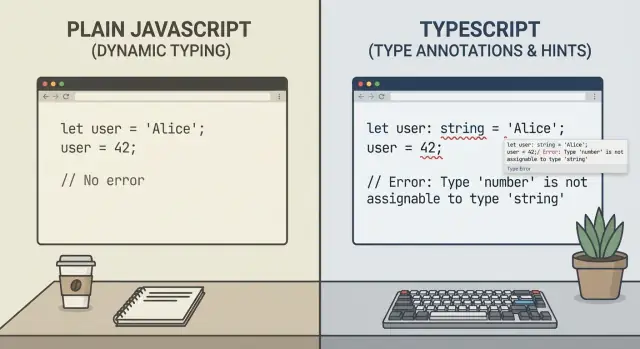

JavaScript vs TypeScript: the plain-English difference

JavaScript is the programming language that runs in every web browser and is widely used on servers (with Node.js). If you’ve ever interacted with a website menu, form validation, or a single-page app, JavaScript is usually doing the work behind the scenes.

TypeScript is JavaScript with an extra “layer” added on top: types. You write TypeScript, but it compiles (transforms) into plain JavaScript that browsers and Node.js can run. That means TypeScript doesn’t replace JavaScript—it depends on it.

What does “types” mean?

A “type” is a label that describes what kind of value something is—like a number, a piece of text, or an object with specific fields. JavaScript figures this out while your code is running. TypeScript tries to check these assumptions before you run the code, so you catch mistakes earlier.

Here’s a simple example:

function totalPrice(price: number, qty: number) {

return price * qty;

}

totalPrice(10, 2); // ok

totalPrice("10", 2); // TypeScript warns: "10" is a string, not a number

In JavaScript, the second call might slip through until it causes a confusing bug later. In TypeScript, you get an early warning in your editor or during your build.

What this guide is (and isn’t)

This isn’t about which language is “better” in the abstract. It’s a practical decision guide: when JavaScript is the simplest choice, when TypeScript pays off, and what trade-offs you’re actually signing up for.

Where TypeScript fits in the JavaScript ecosystem

TypeScript isn’t a separate “replacement” for JavaScript—it’s a superset that adds optional typing and a few developer-focused features on top of standard JS. The key idea: you write TypeScript, but you ship JavaScript.

A quick timeline (why it exists)

TypeScript was created at Microsoft and first released in 2012, when large JavaScript codebases were becoming common in web apps. Teams wanted better tooling (autocomplete, safe refactoring) and fewer runtime surprises, without abandoning the JavaScript ecosystem.

Browsers run JavaScript, not TypeScript

No matter how much TypeScript you use, the runtime environment matters:

- Browsers execute JavaScript.

- Node.js executes JavaScript.

So TypeScript has to be converted into JavaScript before it can run.

The compile/transpile step happens at build time

TypeScript goes through a transpile (compile) step during your build process. That step runs in your tooling—typically on your machine during development and on CI/CD during deployment.

Common setups include:

tsc(the TypeScript compiler)- Bundlers like Vite/Webpack/ESBuild that can handle TypeScript inputs

The output is plain .js (plus optional source maps) that your browser or Node.js can execute.

TypeScript is “plugged into” the existing JS ecosystem

Because TypeScript builds on JavaScript, it works with the same frameworks and platforms: React, Vue, Angular, Express, Next.js, and more. Most popular libraries also publish TypeScript type definitions, either built-in or via the community.

JavaScript and TypeScript can coexist in one repo

A practical reality for many teams: you don’t need an all-or-nothing switch. It’s common to have both .js and .ts files in the same project, gradually converting modules as you touch them, while the app still builds and runs as JavaScript.

Type safety: what you gain (and what you don’t)

Type safety is TypeScript’s headline feature: it lets you describe what shape your data should have, and it checks your code before you run it. That changes when you discover certain mistakes—and how expensive they are to fix.

A tiny JavaScript bug types can catch earlier

Here’s a common JavaScript “looks fine” bug:

function total(items) {

return items.reduce((sum, x) => sum + x.price, 0);

}

total([{ price: 10 }, { price: "20" }]); // "1020" (string concatenation)

This fails quietly at runtime and gives the wrong result. With TypeScript:

type Item = { price: number };

function total(items: Item[]) {

return items.reduce((sum, x) => sum + x.price, 0);

}

total([{ price: 10 }, { price: "20" }]);

// Compile-time error: Type 'string' is not assignable to type 'number'.

That “compile-time error” means your editor/build step flags it immediately, instead of you (or a user) stumbling into it later.

Compile-time vs runtime errors

- Compile-time: TypeScript checks your code and reports type issues during development.

- Runtime: JavaScript executes; if something is wrong (or just weird), you find out while the app is running.

TypeScript reduces a whole category of runtime surprises, but it doesn’t eliminate runtime problems entirely.

The everyday types you’ll use

Most code relies on a few basics:

- Primitives:

string,number,boolean - Collections:

string[](arrays),Item[] - Objects:

{ name: string; isActive: boolean }

Inference: you don’t have to annotate everything

TypeScript often guesses types automatically:

const name = "Ada"; // inferred as string

const scores = [10, 20, 30]; // inferred as number[]

What you don’t gain

- TypeScript doesn’t validate data at runtime (API responses can still be malformed).

- You can opt out with

any, which removes many protections. - Types can be incorrect or outdated—TypeScript will trust what you tell it.

Type safety is best seen as an early-warning system: it catches many mistakes sooner, but you still need testing and runtime checks for untrusted data.

Developer experience and tooling differences

TypeScript’s biggest day-to-day advantage isn’t a new runtime feature—it’s what your editor can tell you while you work. Because the compiler understands the shapes of your data, most IDEs can surface better hints before you ever run the code.

Autocomplete and inline documentation

With plain JavaScript, autocomplete is often based on guesses: naming patterns, limited inference, or whatever runtime info the editor can observe. TypeScript gives the editor a reliable contract.

That shows up as:

- More accurate autocomplete (methods, properties, and function parameters)

- Inline docs that follow types (JSDoc + type definitions), so you can see usage and return values without leaving the file

- Faster feedback when you pass the wrong argument type or forget a required field

In practice, this reduces “tabbing around” to find how something is used—especially in codebases with many utility functions.

Refactoring safety (renames and API changes)

Refactoring in JavaScript can feel risky because it’s easy to miss a stringly-typed reference, a dynamic property, or an indirect import.

TypeScript improves refactoring tools like rename symbol and change signature because the editor can track where a type or function is actually referenced. When an API changes (say a function now returns User | null), TypeScript highlights every spot that needs an update. That’s not just convenience—it’s a way to avoid subtle regressions.

Code reviews: clearer intent, fewer back-and-forths

Types act like lightweight documentation in the code itself. During reviews, it’s often easier to understand intent when you can see:

- What a function expects

- What it guarantees to return

- Which fields are optional vs required

Reviewers spend less time asking “what shape is this object?” and more time on logic, edge cases, and naming.

Navigation in large projects

In bigger apps, TypeScript makes “go to definition” and “find all references” noticeably more dependable. You can jump from a component to its props type, from a function call to an overload, or from a database DTO to the mapping layer—without relying on search and guesswork.

Setup, build pipeline, and everyday workflow

Own the Source Code

Keep full control with source code export when you are ready to move or self-host.

JavaScript runs where it is: in the browser or in Node.js. You can write a .js file and execute it immediately—no compilation step, no config required (beyond whatever your app framework already uses).

TypeScript is different: browsers and Node don’t understand .ts directly. That means you typically add a build step that transpiles TypeScript into JavaScript (and often generates source maps so debugging still points to your original .ts lines).

What “setup” really means

A basic TypeScript setup usually includes:

- Installing TypeScript (

typescript) and often a runner/bundler - Creating a

tsconfig.json - Updating scripts so “dev” compiles on the fly and “build” emits JavaScript

If you’re using a modern tool like Vite, Next.js, or a Node framework, much of this is pre-wired—but TypeScript still adds an extra layer compared to plain JS.

tsconfig.json in plain English

tsconfig.json tells the TypeScript compiler how picky to be and what kind of JavaScript to output. The most important knobs are:

strict: turns on stronger checks (more safety, more initial fixes)target: which JavaScript version to emit (e.g., modern vs older syntax)module: how modules are generated/understood (important for Node vs bundlers)

You’ll also commonly see include/exclude (which files are checked) and outDir (where compiled files go).

Tooling you’ll likely use (JS or TS)

Most teams use the same supporting tools either way: a bundler (Vite/Webpack/esbuild), a linter (ESLint), a formatter (Prettier), and a test runner (Jest/Vitest). With TypeScript, these tools are often configured to understand types, and CI usually adds a dedicated tsc --noEmit type-check step.

Build times and how teams keep them fast

TypeScript can increase build time because it does extra analysis. The good news: incremental builds help a lot. Watch mode, cached builds, and “incremental” compilation mean after the first run, TypeScript often rebuilds only what changed. Some setups also transpile quickly during development and run full type-checking separately, so feedback stays snappy.

Where platforms like Koder.ai can simplify the workflow

Whether you pick JavaScript or TypeScript, teams often spend real time on scaffolding, wiring build tools, and keeping frontend/backend contracts consistent.

Koder.ai is a vibe-coding platform that helps you create web, server, and mobile applications through a chat interface—so you can iterate on features and architecture without getting stuck on repetitive setup. It commonly generates React on the frontend, Go services with PostgreSQL on the backend, and Flutter for mobile, and it supports source code export, deployment/hosting, custom domains, snapshots, and rollback. If you’re experimenting with a JS→TS transition (or starting greenfield), that “planning mode + chat-driven scaffolding” can reduce the cost of trying options and refining structure.

(If you publish content about Koder.ai, there’s also an earn-credits program, plus referrals—useful if you’re already documenting your migration learnings.)

Speed, productivity, and long-term maintenance

It’s tempting to ask “Which one is faster?” but for most real apps, JavaScript and TypeScript end up running at about the same speed. TypeScript compiles to plain JavaScript, and that compiled output is what the browser or Node.js executes. So runtime performance is usually determined by your code and runtime (V8, browser engine), not by whether you wrote .ts or .js.

Development speed: fewer bugs vs more typing

The productivity difference shows up earlier—while you’re writing and changing code.

TypeScript can speed up development by catching mistakes before you run anything: calling a function with the wrong kind of value, forgetting to handle undefined, mixing up object shapes, and so on. It also makes refactors safer: rename a field, change a return type, or reorganize modules, and your editor/CI can point to every place that needs updating.

The trade-off is overhead. You may write more code (types, interfaces, generics), think more upfront, and occasionally wrestle with compiler errors that feel “too strict” for quick ideas. For small scripts or prototypes, that extra typing can slow you down.

Long-term maintenance: where TypeScript shines

Maintainability is mostly about how easy it is for someone—often future you—to understand and modify the code without breaking things.

For long-lived applications, TypeScript tends to win because it encodes intent: what a function expects, what it returns, and what’s allowed. That becomes especially valuable as files multiply, features stack up, and edge cases grow.

Team size matters

For solo developers, JavaScript can be the fastest path from idea to output, especially when the codebase is small and changes are frequent.

For multi-person teams (or multiple teams), TypeScript often pays for itself. Clear types reduce “tribal knowledge,” make code reviews smoother, and prevent integration issues when different people touch the same modules.

When JavaScript is the better choice

TypeScript is great when you want guardrails, but plain JavaScript is still the right tool in plenty of situations. The key question isn’t “Which is better?”—it’s “What does this project need right now?”

Small scripts, prototypes, and throwaway demos

If you’re hacking together a quick script to rename files, scrape a page, or test an API idea, JavaScript keeps the feedback loop tight. You can run it immediately with Node.js, share a single file, and move on.

For prototypes and demo apps that might be rewritten (or abandoned), skipping types can be a reasonable trade-off. The goal is learning and validation, not long-term maintenance.

Learning projects and teaching fundamentals

When someone is new to programming or new to the web, JavaScript reduces cognitive load. You can focus on core concepts—variables, functions, async/await, DOM events—without also learning type annotations, generics, and build configuration.

If you’re mentoring or teaching, JavaScript can be a clearer starting point before adding TypeScript later as a “next layer.”

Minimal libraries that prioritize flexibility

Some libraries are intentionally small and permissive. For utilities meant to be dropped into many environments, JavaScript can be simpler to publish and consume—especially when the API surface is tiny and the project already has strong documentation and tests.

(You can still provide TypeScript typings later, but it doesn’t have to be the core source language.)

When build steps are undesirable

TypeScript usually adds a compilation step (even if it’s fast). For simple embeds—like a widget snippet, a bookmarklet, or a small script dropped into a CMS—JavaScript is often a better fit because you can ship a single file with no tooling required.

If your constraints are “copy/paste and it works,” JavaScript wins on practicality.

A good rule of thumb

Choose JavaScript when speed of experimentation, zero-config delivery, or broad compatibility matters more than long-term guarantees. If the code is expected to live for months or years and evolve with a team, TypeScript tends to pay back that upfront cost—but JavaScript remains a perfectly valid default for smaller, simpler work.

When TypeScript is the better choice

Get Rewarded for Sharing

Document your JS to TS learnings and earn credits for creating content about Koder.ai.

TypeScript tends to pay off when your codebase has enough moving parts that “remembering what goes where” becomes a real cost. It adds a layer of checked structure on top of JavaScript, which helps teams change code confidently without relying solely on runtime testing.

Medium/large apps with many modules and contributors

When multiple people touch the same features, the biggest risk is accidental breakage: changing a function signature, renaming a field, or using a value in the wrong way. TypeScript makes those mistakes visible while you code, so the team gets faster feedback than “wait for QA” or “discover it in production.”

Apps with frequent refactors or changing requirements

If your product evolves quickly, you’ll refactor often: moving logic between files, splitting modules, extracting reusable utilities. TypeScript helps you refactor with guardrails—your editor and compiler can point out all the places that must change, not just the ones you remember.

Shared code across frontend and backend (Node.js)

If you share types or utilities between a frontend and a Node.js backend, TypeScript reduces mismatches (for example, a date string vs a timestamp, or a missing field). Shared typed models also make it easier to keep API request/response shapes consistent across the app.

APIs and SDKs where typed contracts reduce support issues

If you publish an API client or SDK, TypeScript becomes part of the “product experience.” Consumers get autocomplete, clearer docs, and earlier errors. That typically translates to fewer integration problems and fewer support tickets.

If you’re already leaning toward TypeScript, the next practical question is how to introduce it safely—see /blog/migrating-from-javascript-to-typescript-without-disruption.

Learning curve: what trips people up

TypeScript is “just JavaScript with types,” but the learning curve is real because you’re learning a new way of thinking about your code. Most friction comes from a few specific features and from compiler settings that feel picky at first.

The common pain points

Unions and narrowing surprise many people. A value typed as string | null is not a string until you prove it. That’s why you’ll see patterns like if (value) { ... } or if (value !== null) { ... } show up everywhere.

Generics are the other big hurdle. They’re powerful, but it’s easy to overuse them early on. Start by recognizing them in libraries (Array<T>, Promise<T>) before writing your own.

Configuration can also be confusing. tsconfig.json has lots of options, and a couple of them change your daily experience dramatically.

Strict mode: why it feels harder (and why it’s worth it)

Turning on "strict": true often creates a wave of errors—especially around any, null/undefined, and implicit types. That can feel discouraging.

But strict mode is where TypeScript pays off: it forces you to handle edge cases explicitly, and it prevents “it worked until production” bugs (like missing properties or unexpected undefined). A practical approach is to enable strict mode in new files first, then expand.

Tips for learning without fighting your code

Start with TypeScript’s type inference: write normal JavaScript, let the editor infer types, and only add annotations where the code is unclear.

Add types gradually:

- Type function inputs/outputs first (high leverage).

- Use unions for real-world data (optional fields, API responses).

- Rely on narrowing patterns (

typeof,in,Array.isArray).

Mistakes to avoid

Two classic traps:

- Over-typing: adding verbose types everywhere instead of letting inference work.

- Fighting the compiler: using

as anyto “make errors go away” rather than fixing the underlying assumption.

If TypeScript feels strict, it’s usually pointing at an uncertainty in your code—turning that uncertainty into something explicit is the core skill to build.

Migrating from JavaScript to TypeScript without disruption

Ship a Working Build

Deploy and host your app without wiring up a separate pipeline.

You don’t have to “stop the world” to adopt TypeScript. The smoothest migrations treat TypeScript as an upgrade path, not a rewrite.

Start with a mixed repo

TypeScript can live alongside existing JavaScript. Configure your project so .js and .ts files can coexist, then convert file-by-file as you touch code. Many teams begin by enabling allowJs and checkJs selectively, so you can get early feedback without forcing a full conversion.

Phase it: types for new code first

A practical rule: new modules are TypeScript, existing modules stay as-is until they need changes. This immediately improves long-term maintenance because the code that will grow the most (new features) gains types first.

Third-party libraries and type definitions

Most popular packages already ship TypeScript types. If a library doesn’t, look for community-maintained definitions (often published as @types/...). When nothing exists, you can:

- add a minimal local declaration file for the parts you use

- wrap the library behind a small typed adapter so the “untyped edge” doesn’t spread

Use escape hatches carefully

You’ll occasionally need to bypass the type system to keep moving:

unknownis safer thananybecause it forces checks before use- type assertions can unblock progress, but treat them as “TODO: prove this”

The goal isn’t perfection on day one—it’s to make unsafe spots visible and contained.

Add guardrails to prevent backsliding

Once TypeScript is in place, protect the investment:

- lint rules to discourage

anyand unsafe assertions - CI that runs type-checking on every pull request

- code review expectations (for example: new public functions must have typed inputs/outputs)

Done well, migration feels incremental: each week a little more of the codebase becomes easier to navigate, refactor, and ship confidently.

Decision checklist and next steps

If you’re still on the fence, decide based on the realities of your project—not ideology. Use the checklist below, do a quick risk scan, then pick a path (JavaScript, TypeScript, or a hybrid).

Quick checklist

Ask these before you start (or before you migrate):

- Project size: small script, medium app, or large product with many modules?

- Team size: solo, a small team, or multiple squads touching the same code?

- Expected lifespan: weeks/months vs. multi-year maintenance?

- Release cadence: occasional releases vs. daily/weekly shipping?

As a rule of thumb: the bigger the codebase and the more people involved, the more TypeScript pays back.

Risk assessment (what can hurt you most?)

- Bug risk: If runtime bugs are expensive (payments, auth, healthcare), TypeScript’s checks reduce common mistakes—especially during refactors.

- Onboarding time: If new developers join often, TypeScript can document intent through types and editor hints.

- Build complexity: TypeScript adds compilation and configuration. If you need the simplest possible setup, JavaScript stays lighter.

Simple recommendation matrix

- Choose JavaScript when: the project is small, speed of setup matters, requirements change daily, or you’re prototyping.

- Choose TypeScript when: the app will grow, multiple people contribute, you refactor often, or correctness matters.

- Choose hybrid when: you have an existing JS codebase—start with TypeScript for new files or critical modules, and migrate gradually.

Next steps

- Pick a path for the next 30–60 days (not forever).

- Define “success”: fewer production bugs, faster onboarding, safer refactors, or quicker iteration.

- Re-evaluate after a couple of releases.

If you want help choosing and implementing the right setup (JS, TS, or hybrid), see our plans at /pricing.