Oct 20, 2025·8 min

Jay Chaudhry & Zscaler: Zero Trust Built for Cloud Scale

A practical look at how Jay Chaudhry and Zscaler used cloud security, zero trust, and partner distribution to build a leading enterprise security company.

A practical look at how Jay Chaudhry and Zscaler used cloud security, zero trust, and partner distribution to build a leading enterprise security company.

This isn’t a biography of Jay Chaudhry. It’s a practical story about how Zscaler helped reshape enterprise security—and why its choices (technical and commercial) mattered.

You’ll learn two things in parallel:

Modern enterprise security is the set of controls that lets employees use the internet and internal apps safely, without assuming anything is safe just because it sits “inside” a corporate network. It’s less about building a bigger wall around a data center, and more about checking who is connecting, what they’re connecting to, and whether the connection should be allowed—every time.

By the end, you’ll be able to explain Zscaler’s core bet in one sentence, recognize where zero trust replaces VPN-era thinking, and see why distribution strategy can matter as much as product design.

Jay Chaudhry is a serial entrepreneur best known as the founder and CEO of Zscaler, a company that helped push enterprise security from “protect the corporate network” to “secure users and apps wherever they are.” Before Zscaler, he built and sold multiple security startups, giving him a front-row view of how quickly attacker behavior and enterprise IT were changing.

Chaudhry’s focus with Zscaler was straightforward: as work and applications moved off the corporate network (toward the public internet and cloud services), the old model of routing everything through a central data center for inspection started breaking down.

That shift created a painful trade-off for IT teams:

Zscaler’s founding premise was that security needed to follow the user, not the building.

What stands out is how founder-led product vision influenced the company’s strategy early:

This wasn’t a marketing tweak; it drove product decisions, partnerships, and how Zscaler explained the “why” to conservative enterprise buyers. Over time, that clarity helped turn “cloud-delivered security” and “zero trust” from ideas into budget lines—something big companies could buy, deploy, and standardize.

For years, enterprise security was built around a simple idea: keep the “good stuff” inside the corporate network, and put a wall around it. That wall was usually a stack of on‑prem appliances—firewalls, web proxies, intrusion prevention—sitting in a few data centers. Remote employees got in through a VPN, which effectively “extended” the internal network to wherever they were.

When most apps lived in company data centers, this worked reasonably well. Web traffic and app traffic flowed through the same chokepoints, where security teams could inspect, log, and block.

But the model assumed two things that started becoming untrue:

As employees became more mobile and SaaS adoption accelerated, traffic patterns flipped. People in coffee shops needed fast access to Office 365, Salesforce, and dozens of browser-based tools—often without ever touching a corporate data center.

To keep enforcing policy, many companies “backhauled” traffic: send a user’s internet and SaaS requests through HQ first, inspect it, then send it back out. The result was predictable: slow performance, unhappy users, and growing pressure to punch holes in controls.

Complexity spiked (more appliances, more rules, more exceptions). VPNs became overloaded and risky when they granted broad network access. And every new branch office or acquisition meant another hardware rollout, more capacity planning, and more brittle architecture.

That gap—needing consistent security without forcing everything through a physical perimeter—created the opening for cloud-delivered security that could follow the user and the application, not the building.

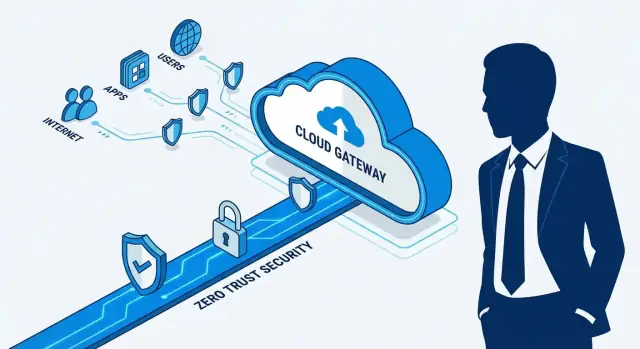

Zscaler’s defining bet was simple to say but hard to execute: deliver security as a cloud service, positioned close to users, instead of as boxes sitting inside a company’s network.

In this context, “cloud security” doesn’t mean protecting cloud servers only. It means the security itself runs in the cloud—so a user in a branch office, at home, or on mobile connects to a nearby security point-of-presence (PoP), and policy is enforced there.

“Inlining” is like routing traffic through a security checkpoint on the way to its destination.

When an employee goes to a website or a cloud app, their connection is steered through the service first. The service inspects what it can (based on policy), blocks risky destinations, scans for threats, and then forwards allowed traffic onward. The goal is that users don’t need to “be on the corporate network” to get corporate-grade protection—security travels with the user.

Cloud-delivered security changes the day-to-day reality for IT and security teams:

This model also aligns with how companies actually work now: traffic often goes directly to SaaS and the public internet, not “back to headquarters” first.

Putting a third party inline raises real concerns that teams must evaluate:

The core bet, then, isn’t only technical—it’s operational confidence that a cloud provider can enforce policy reliably, transparently, and at global scale.

Zero trust is a simple principle: never assume something is safe just because it’s “inside the company network.” Instead, always verify who the user is, what device they’re on, and whether they should access a specific app or piece of data—every time it matters.

Traditional VPN thinking is like giving someone a badge that opens a whole building once they’re through the front door. After the VPN connects, many systems treat that user as “internal,” which can expose more than intended.

Zero trust flips that model. It’s more like giving someone access to one room for one task. You don’t “join the network” broadly; you’re allowed to reach only the app you’re approved for.

A contractor needs access to a project management tool for two months. With zero trust, they can be allowed into that single app—without accidentally getting a pathway to payroll systems or internal admin tools.

An employee uses BYOD (their own laptop) while traveling. Zero trust policies can require stronger login checks or block access if the device is outdated, unencrypted, or showing signs of compromise.

Remote work becomes easier to secure because the security decision follows the user and the app, not a physical office network.

Zero trust isn’t one product you buy and “turn on.” It’s a security approach implemented through tools and policies.

It also doesn’t mean “trust nobody” in a hostile way. In practice, it means trust is earned continuously through identity checks, device posture, and least-privilege access—so mistakes and breaches don’t automatically spread.

Zscaler is easiest to understand as a cloud “control point” that sits between people and what they’re trying to reach. Instead of trusting a corporate network boundary, it evaluates each connection based on who the user is and what the situation looks like, then applies the right policy.

Most deployments can be described with four simple pieces:

Conceptually, Zscaler splits traffic into two lanes:

That separation matters: one lane is about safe internet use; the other is about precise access to internal systems.

Decisions aren’t based on a trusted office IP address. They’re based on signals such as who the user is, device health (managed vs. unmanaged, patched vs. outdated), and where/how they’re connecting.

Done well, this approach reduces the exposed attack surface, limits lateral movement if something goes wrong, and turns access control into a simpler, consistent policy model—especially as remote work and cloud-first application stacks become the default.

When people talk about “enterprise security,” they often picture private apps and internal networks. But a huge share of risk sits on the open internet side: employees browsing news sites, clicking links in email, using browser-based tools, or uploading files to web apps.

A Secure Web Gateway (SWG) is the category built to make that everyday internet access safer—without forcing every user’s traffic to hairpin through a central office.

At its simplest, an SWG acts as a controlled checkpoint between users and the public web. Instead of trusting whatever a device reaches, the gateway applies policy and inspection so organizations can reduce exposure to malicious sites, risky downloads, and accidental data leakage.

Typical protections include:

The momentum shift came as work moved away from fixed offices and toward SaaS, browsers, and mobile devices. If users are everywhere and apps are everywhere, backhauling traffic to a single corporate perimeter adds latency and creates blind spots.

Cloud-delivered SWG matched the new reality: policy follows the user, traffic can be inspected closer to where they connect, and security teams get consistent control across headquarters, branches, and remote work—without treating the internet like an exception.

VPNs were built for a time when “being on the network” was the same as “being able to reach the apps.” That mental model breaks down when apps live across multiple clouds, SaaS, and a shrinking set of on‑prem systems.

App-centric access flips the default. Instead of dropping a user onto the internal network (and then hoping segmentation policies hold), the user is connected only to a specific application.

Conceptually, it works like a brokered connection: the user proves who they are and what they’re allowed to use, and then a short, controlled path is created to that app—without publishing internal IP ranges to the internet and without giving the user broad “internal” visibility.

Network segmentation is powerful, but it’s also fragile in real organizations: mergers, flat VLANs, legacy apps, and exceptions tend to accumulate. App segmentation is easier to reason about because it maps to business intent:

This reduces implicit trust and makes access policies readable: you can audit them by application and user group instead of tracing routes and subnets.

Most teams don’t replace VPN overnight. A practical rollout often looks like:

When app-centric access is done well, the gains show up quickly: fewer VPN-related support tickets, clearer access rules that security and IT can explain, and a smoother user experience—especially for remote and hybrid employees who just want the app to work without “connecting to the network” first.

Great security products don’t automatically become enterprise standards. In practice, “distribution” in enterprise security means the set of routes a vendor uses to reach, win, and successfully deploy inside big organizations—often through other companies.

In security, distribution typically spans:

These aren’t optional add-ons. They’re the pipes that connect a vendor to budgets, decision makers, and implementation capacity.

Large enterprises buy with caution. Partners provide:

For a platform like Zscaler, adoption often depends on real-world migration work—moving users off legacy VPN patterns, integrating identity, and tuning policies. Partners can make that change feel manageable.

Cloud delivery shifts the business from one-time installs to subscription, expansion, and renewals. That changes distribution: partners aren’t only “deal closers.” They can be ongoing rollout partners whose incentives align with customer outcomes—if the program is designed well.

Look closely at partner incentives, the quality of partner enablement (training, playbooks, co-selling support), and how cleanly customer success handoffs work after the contract is signed. Many deployments fail not because the product is weak, but because ownership between vendor, partner, and customer becomes unclear.

Security buying rarely starts with “we need better security.” It usually starts with a network change that breaks the old assumptions: more apps move to SaaS, branches switch to SD-WAN, or remote work becomes permanent. When traffic no longer flows through a central office, the “protect everything at headquarters” model turns into slow connections, messy exceptions, and blind spots.

Zscaler is often mentioned in the same conversations as SASE and SSE because those labels describe a shift in how security is delivered:

The real “benefit translation” isn’t the acronym—it’s simpler operations: fewer on-prem boxes, easier policy updates, and more direct access to apps without hairpinning traffic through a data center.

A company typically evaluates SSE/SASE-style approaches when:

When those triggers show up, the category “arrives” naturally—because the network has already changed.

Buying a Zero Trust platform is usually the easy part. Making it work across messy networks, inherited applications, and real people is where projects succeed—or stall.

Legacy apps are the repeat offender. Older systems may assume “inside the network = trusted,” rely on hard-coded IP allowlists, or break when traffic is inspected.

The other friction points are human: change management, policy redesign, and “who owns what” debates. Moving from broad network access to precise, app-level rules forces teams to document how work actually happens—and that can surface long-ignored gaps.

Rollouts go smoother when security doesn’t try to operate alone. Expect to coordinate with:

Start with a low-risk group (e.g., a single department or a subset of contractors) and define success metrics upfront: fewer VPN tickets, faster app access, measurable reduction in exposed attack surface, or improved visibility.

Run the pilot in iterations: migrate one app category at a time, tune policies, then expand. The goal is to learn quickly without turning the whole company into a test environment.

Plan for logging and troubleshooting from day one: where logs live, who can query them, how long they’re retained, and how alerts tie into incident response. If users can’t get help when “the app is blocked,” confidence drops fast—even if the security model is sound.

A practical (and often overlooked) accelerant here is internal tooling: simple portals for exception requests, access reviews, app inventories, rollout tracking, and reporting. Teams increasingly build these lightweight “glue apps” themselves rather than waiting for a vendor roadmap. Platforms like Koder.ai can help teams prototype and ship these internal web tools quickly via a chat-driven workflow—useful when you need a React-based dashboard with a Go/PostgreSQL backend, plus fast iterations as policies and processes mature.

Moving security controls from appliances you own to a cloud-delivered platform can simplify operations—but it also changes what you’re betting on. A good decision is less about “Zero Trust vs. legacy” and more about understanding the new failure modes.

If one platform provides web security, private app access, policy enforcement, and logging, you reduce tool sprawl—but you also concentrate risk. A contract dispute, a pricing shift, or a product gap can have wider blast radius than when those pieces were spread across multiple tools.

Cloud security adds an extra hop between users and apps. When it works well, users barely notice. When a region has an outage, routing issue, or capacity problem, “security” can look like “the internet is down.” This is less about any single vendor and more about relying on always-on connectivity.

Zero Trust isn’t a magic shield. Poorly scoped policies (too permissive, too restrictive, or inconsistent across groups) can either increase exposure or interrupt work. The more flexible the policy engine, the more discipline you need.

Phased rollouts help: start with a clear use case (e.g., a subset of users or one app category), measure latency and access outcomes, then expand. Define policies in plain language, implement monitoring and alerting early, and plan redundancy (multi-region routing, break-glass access, and documented fallback paths).

Know what data types you’re protecting (regulated vs. general), align controls to compliance needs, and schedule recurring access reviews. The goal isn’t fear-based buying—it’s making sure the new model fails safely and predictably.

Zscaler’s repeatable lesson is focus: move security enforcement to the cloud and make access identity-driven. When evaluating vendors (or building one), ask a simple question: “What is the one architectural bet that makes everything else simpler?” If the answer is “it depends,” expect complexity to show up later in cost, rollout time, and exceptions.

“Zero trust” worked because it translated into a practical promise: fewer implicit trust assumptions, less network plumbing, and better control as apps moved off-prem. For teams, this means buying outcomes, not buzzwords. Write down your desired outcomes (e.g., “no inbound access,” “least-privilege to apps,” “consistent policy for remote users”) and map each to concrete capabilities you can test.

Enterprise security spreads through trust networks: resellers, GSIs, MSPs, and cloud marketplaces. Founders can copy this by building a partner-ready product early—clear packaging, predictable margins, deployment playbooks, and shared metrics. Security leaders can leverage partners too: use them for change management, identity integration, and phased migrations instead of trying to upskill every team at once.

Start with one high-volume use case (often internet access or a single critical app), measure before/after, and expand.

Key rollout questions:

Don’t just “sell security”—sell a migration path. The winning story is usually: pain → simplest first step → measurable win → expansion. Build the onboarding and reporting that makes value visible in 30–60 days.

One founder-friendly pattern is to complement the core product with fast-to-build companion apps (assessment workflows, migration trackers, ROI calculators, partner portals). If you want to create these without rebuilding a full legacy dev pipeline, Koder.ai is designed for “vibe-coding” full-stack apps from chat—useful for getting internal or customer-facing tooling into production quickly, then iterating as your distribution motion evolves.

If you want to go deeper, see /blog/zero-trust-basics and /blog/sase-vs-sse-overview. For packaging ideas, visit /pricing.

Zero trust is an approach where access decisions are made per request based on identity, device posture, and context, rather than assuming something is safe because it’s “inside the network.” Practically, it means:

A traditional VPN often places a user “on the network,” which can unintentionally expose more systems than needed. App-centric access flips the model:

“Inline” means traffic is routed through a security checkpoint before it reaches the internet or a cloud app. In a cloud-delivered model, that checkpoint lives in a nearby point of presence (PoP), so the provider can:

The goal is consistent security without forcing traffic back through headquarters.

Backhauling sends a remote user’s web and SaaS traffic to a central data center for inspection, then back out to the internet. It commonly fails because it:

A Secure Web Gateway (SWG) protects users as they browse the internet and use SaaS apps. Common SWG capabilities include:

It’s especially useful when most traffic is internet-bound and users aren’t sitting behind a single corporate firewall.

Cloud-delivered security can simplify operations, but it changes what you depend on. Key trade-offs to evaluate:

A low-risk pilot usually succeeds when it is narrowly scoped and measurable:

The goal is learning fast without making the whole company a test environment.

Misconfiguration is common because moving from “network access” to “app/policy access” forces teams to define intent precisely. To reduce risk:

SSE is cloud-delivered security controls (like SWG and private app access) delivered at the “edge,” close to users. SASE combines that security model with the networking side (often SD-WAN) so connectivity and security are designed together.

In buying terms:

Big enterprises often buy through partners and need implementation capacity. Channel partners, SIs, and MSPs help by:

A strong partner ecosystem can determine whether a platform becomes a standard or stalls after a small deployment.